May 15, 2024

In this guest post, Frank Abe introduces a selection from the new anthology, The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration, which he co-edited with Floyd Cheung. The book was published this week by Penguin Classics.

With our new anthology Floyd Cheung and I have sought to reclaim and reframe the writing produced by the people targeted by wartime exclusion and incarceration based solely on race. Despite their wide range of backgrounds and experiences, what emerges from the pages is the collective voice of a people pushing back against the increasing dehumanization they feel from a succession of government orders and administrative edicts.

In place of familiar selections readily found elsewhere, our volume recovers pieces that have been long overlooked on the shelf, buried in the archives, or languished unread in the Japanese language. The eighteen translations from the Japanese we present attest to one of the long-term effects of the camps: the loss of language and culture due to regulation, suppression, and the ongoing stigma of acknowledging any affinity to Japan. We never knew of these writings because we couldn’t read them. With our anthology we have scratched the surface of writing from the camps that is still out there waiting to be read.

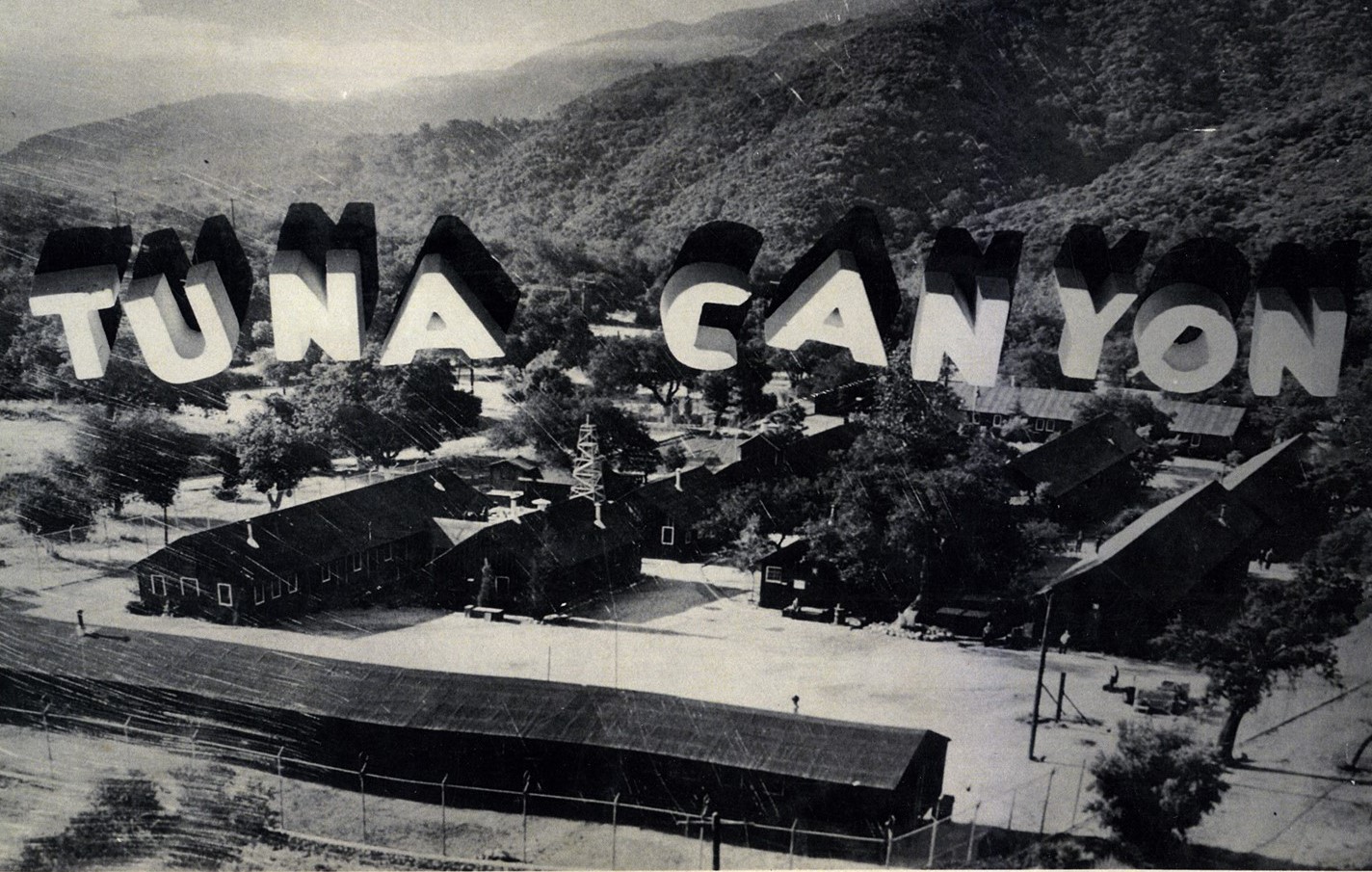

For this volume we commissioned two new translations of stories from Tessaku, or Iron Fence, the literary journal of the Tule Lake Segregation Center. Our research has revealed that Tessaku was founded in response to the disturbance that led to creation of the Tule Lake Stockade, a prison within a prison. The story that follows was written by Fujiwo Tanisaki when he was just 23, a Kibei Nisei living in Los Angeles with a wife and child when he was forcibly removed to Manzanar. He continued writing there, and there is evidence that he entered this piece in a short story contest conducted by the editors of Tessaku. Tanisaki creates the character of a Nisei son who returns home to learn the FBI has arrested his father and taken him, judging from the internal evidence, to the Tuna Canyon Detention Station, a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp near Los Angeles. This version of the text is slightly edited for content.

“They Took Our Father Too”

by Fujiwo Tanisaki

Translated by Andrew Way Leong

Even after the war started, they continued the project of cleaning city hall. Workers, precariously perched on long planks suspended by ropes, had been washing the dirt-stained walls by hand. The upper portion of the tower was now a pure white, stretching up into the blue sky. The trees surrounding the building were just beginning to sprout their first young buds, and a soft breeze blew gently through the clear air. All signs pointed toward a light and pleasant spring, but the shouts of the newspaperman and the news on the radio drifting out of a nearby bar … all of those sounds stung the ears of Kenji, a boy with a Japanese face. With these sounds gathering, lurking behind his back, pressing down upon him, there was no hope of feeling bright and cheerful.

Kenji was in junior high…. In Japantown, more and more stores were closing by the day, and the Japanese people on the streets all seemed to be in a hurry, dark expressions clouding their faces. All sorts of furniture and household goods had been brought out onto the sidewalks… Scraps of paper littered the front of the Asia Emporium, which had finished its closing clearance sale. The inside of the store was dark, with nothing left but dust. The window display was empty, but a few people had gathered to read a sign that was posted there. The sign was in Japanese.

One of the old men raised his voice as he read. He looked at the map displayed on one side and muttered, “Looks like it’s not our turn just yet. I wonder when we’ll have to go…”

“We’ll go whenever we end up going,” snapped the man standing next to him. Another man, tall and ungainly, drew a breath from his unlit pipe.

“No need to rush. Wherever we’re going, it’s nowhere nice. I’m happy staying right here, even if it’s not for long.” The tall man laughed. Everyone laughed.

Today, it seemed, another exclusion zone had been announced. The area on the map marked out with the red-penciled line had grown once again.

Kenji returned home. He opened the door and saw the desolation. Most of the furniture was gone. Even the carpet had been rolled up and sold off. It was quiet, as if no one was home, and the last remaining items—an antique electric stove, a broken radio—had been pushed into a corner. His father had been busy making crates, well into the night, to store their valuables. “Sooner or later we’re going to get the evacuation order, so best be prepared,” he would say. He was taking care of things. That’s why there was a pile of half-finished crates in the parlor, and scraps of wood, a hammer, a saw, a sewing box…. Kenji sat down on one of the crudely constructed crates, and strange and half-formed apprehensions played out before his eyes, one after another.

Just then, he overheard the voice of his mother. She was on the telephone upstairs. “Yes. The FBI came this morning around ten…” “No.” “We knew this would happen eventually, so we were prepared.” Kenji stood up with a start, realizing that his father must have been taken. Then he sat back down. At dinnertime, and other times, his father would often say, “They’re coming to get me any day now.” The image of Father’s face as he would say this, half joking, floated into Kenji’s mind. His mother had already packed his things into a suitcase so that he would be ready to go at a moment’s notice. Kenji could imagine, with brilliant clarity, how his small-statured father would have been holding that suitcase when the tall white men came to get him. The tears that Kenji had been holding back began to stream down his face.

“I’m home!” His older sister Shizuko was at the door. Kenji stood up and wiped away his tears. His sister took one look at him and asked, “What’s wrong? Why are you crying?” His mother came down the stairs. She had a grave expression on her face, and seemed a little pale, but did not say a word. Shizuko tried to say something, but broke down in tears instead.

It took about a week, after asking for some help from a kind white person, to find out where Father was being held. It turned out that he was pretty far away. He was in a CCC camp thirty miles out, so they had to ask around the neighborhood for someone who could drive the family’s car. Kenji’s mother observed aloud, to anyone listening, “The car still has payments left. The company’s going to come for it any day now. Good thing we still have it.” Everyone was talking about what they imagined Father’s life was like in the camp. Kenji didn’t say out loud what he was thinking, that they were probably giving his father a really hard time. Soon enough, his sister said what Kenji was only thinking. Mother, appearing as if she had expected this all along, said, “Shizuko, that’s enough. Stop thinking those kinds of thoughts.” She turned away and looked out the window. It was clear and sunny, an unusually warm day for that time of year. “This would have been a nice place for a picnic,” she said, almost whispering. Kenji thought that even if it was going to be picnic season soon, for Japanese like him, happy things like picnics were something far away now, lost in the distance.

The road turned sharply as they went deeper into the mountains, and they soon arrived at a place where crowds of visitors were waiting in long lines. The camp was at the bottom of a ravine, surrounded by barbed wire. There were also visitors trying to speak through the metal fences. People who had said their goodbyes were turning back, their eyes red from trying to wipe away their tears. The first impression was one of overwhelming sadness.

“Let’s try not to cry,” Kenji’s sister whispered into their mother’s ear.

Their names were called earlier than they expected. Kenji was walking closely behind his mother and sister as they made their way to the metal fence, but he could not see his father.

Someone called out his father’s name. Then he was there. He was looking from side to side, trying to find his family, and when he finally saw them he pushed his way through the people in front of him and pressed up against the fence. Kenji’s mother began to speak. His sister wiped her face with her handkerchief. Speak English!! a guard yelled out. All right, his father said. It was in that moment, as his father was turning to look up at the guard, that Kenji realized how pale his father’s face was, how dark and sunken his eyes were. Kenji’s mother looked down at the scraps of paper she had prepared, and while continuing to speak in Japanese, threw in loud ands and buts to make it sound like she was speaking in English.

Through this difficult method, she was able to get across all that needed to be said. Two minutes was hardly enough time to describe all that had happened in the last week, but the important details were exchanged nevertheless. Next was Shizuko, who quickly said, “We brought you some clothes and other things. It sounds like they’ll give them to you once they clear inspection.” Kenji wanted to say something as well, but he had no idea what he should say. His father asked him, “You still studying hard?” Kenji just nodded. His face was so stiff he couldn’t even smile. The guard came between them. Father told them not to worry, it would all be fine. Shizuko was sobbing. The people waiting behind them could see everything, so Kenji tried not to cry.

As they walked to the car, they turned to look back at the camp, and they saw a man, a man who could have been Father, waving his hat high above his head. It was hard to tell if it was him through their tears. They waved back. Their feet grew heavy. When they got into the car and looked back again, they could no longer see the man. There was only the metal fence, gleaming in the sharp, white sunlight.

—

Fujiwo Tanisaki, “They Took Our Father Too” (Chichi mo hipparareta), in Tessaku, vol. 2 (May 15, 1944). Used by permission of Diane Rico. Translation copyright © 2024 by Andrew Way Leong. Excerpted from The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration, edited by Frank Abe and Floyd Cheung and available now from Penguin Classics.

Join Frank Abe, Floyd Cheung, and Andrew Way Leong on October 10 for Densho’s 2024 Virtual Fundraiser! Make sure to grab your tickets for Unearthing History: Planting the Seeds for Densho’s Legacy.

Make a gift to Densho to support the Catalyst!

[Header: A model of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station. Courtesy of the Merrill H. Scott Family and Little Landers Historical Society.