October 17, 2024

At a rally in Aurora, Colorado last week, former president and 2024 Republican nominee Donald Trump made a disturbing promise to round up and deport millions of immigrants if elected. While this anti-immigrant rhetoric is not new for the Trump campaign, what grabbed headlines this time around was his invocation of an 18th century law that grants the president sweeping power to detain and deport foreign nationals. That law, the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, was the same legislation that provided the legal basis for the internment and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

So what is the Alien Enemies Act, and is it as dangerous as it sounds?

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 was part of the Alien and Sedition Acts, a series of four laws passed on the eve of war with France. This charge was led by a Federalist-controlled Congress that viewed political dissent as disloyalty and feared non-citizen “aliens” would rise up to support their countries of origin in overthrowing the United States. (Sound familiar? Turns out nationalism and xenophobia are an American tradition!)

These laws — which were widely denounced for restricting freedom of speech and later contributed to the Federalists’ defeat in the election of 1800 — placed regulations on the press, raised the residency requirements for citizenship, and made aliens “liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed” in the event of war with their nation of origin. As of 2024, it remains on the books, in modified form, and authorizes the President to detain and deport enemy aliens in time of war.

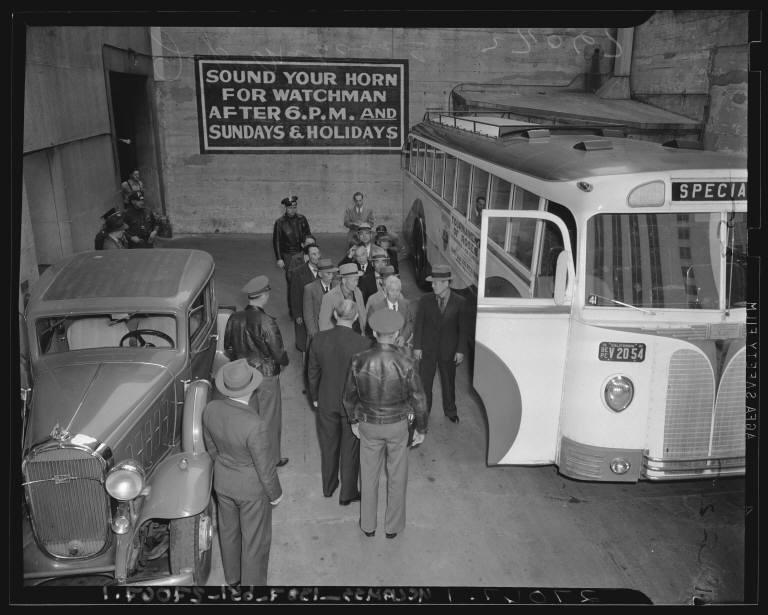

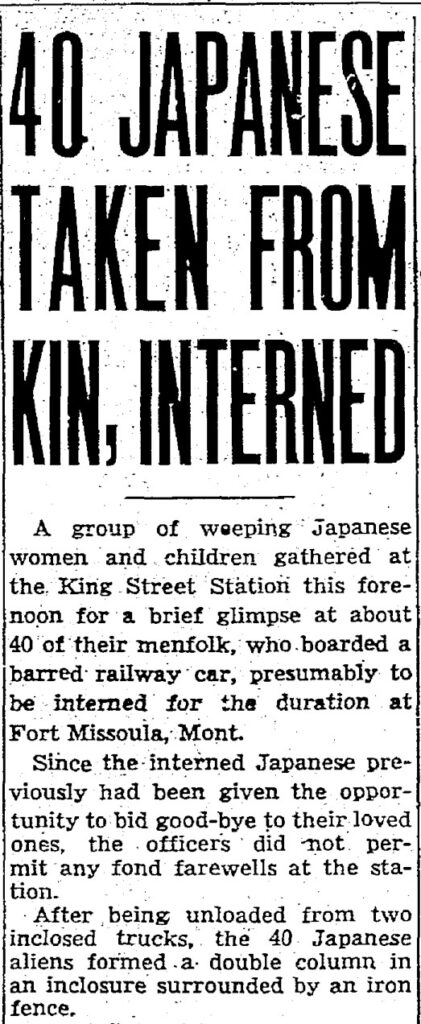

During World War II, immediately after the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt invoked the Alien Enemies Act to authorize the government to detain enemy aliens and confiscate enemy property. Within hours of the attack, federal and local law enforcement began arresting Japanese immigrants as “enemy aliens” and suspected saboteurs — before an actual declaration of war, and largely without warrants or formal charges.

On December 8, similar proclamations were issued for the arrest of German and Italian nationals. By February 16, 1942, the Department of Justice held 2,192 Japanese, 1,393 Germans, and 264 Italians in their custody — and that number continued to climb higher with ongoing arrests.

In the weeks following Pearl Harbor, these raids became such a regular occurrence that many Issei men began to keep a suitcase with a toothbrush and change of clothes by the door, in case they were next to disappear. FBI agents pushed their way into Japanese American homes, crashed community events and even weddings to carry out arrests, often with no word on where they were being taken and when, or if, they would be allowed to return.

“It was the first time I saw my mom cry,” recalled Mako Nakagawa, whose father was arrested in February 1942. “It was on my sister’s eleventh birthday. That day we were supposed to celebrate her eleventh birthday when they came and took him away. My father thought that they would go through some questioning and then he will be home in time for birthday cake. He really thought that if you answer the question, cooperate, he will be home in time for dinner and have birthday with the kids. Well, he wasn’t reunited with the family for a couple years.”

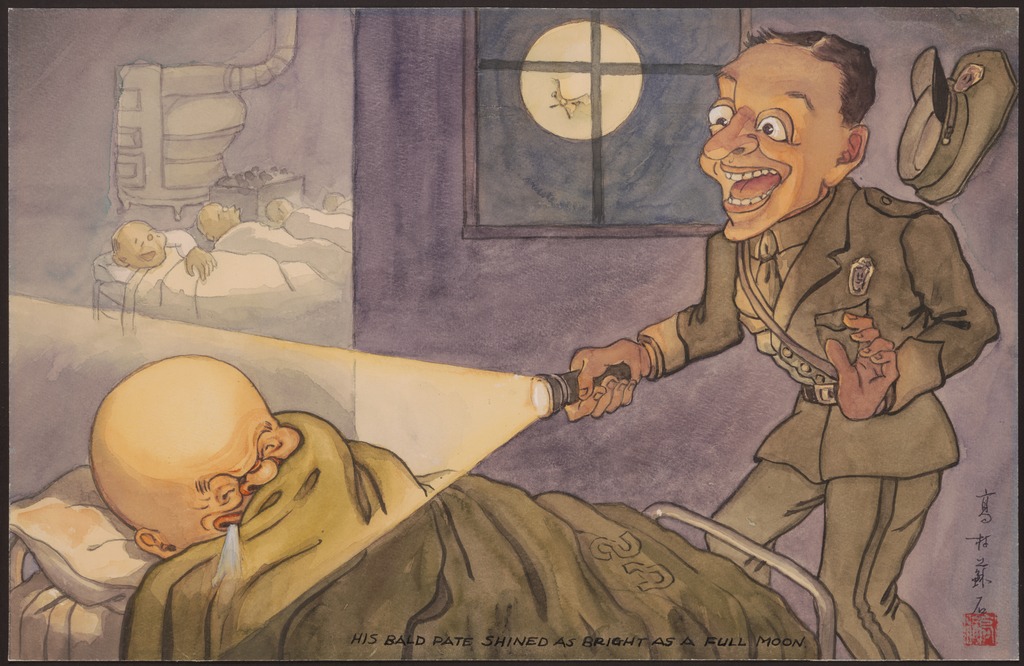

But this roundup of “enemy aliens” was fueled by more than simple wartime hysteria. As early as the 1920s, the government had prepared for the detention of prominent Issei, made contingency plans for the systematic removal of Nikkei communities, and even toyed with the idea of holding Japanese Americans as wartime hostages. This surveillance ramped up during the 1930s as a likely war with Japan loomed closer. Officials began to compile lists of “potentially subversive” individuals and organizations, often resorting to illegal wiretaps, break-ins, opening mail, accessing private bank accounts, and in one case even “borrowing” a safecracker from a local prison to aid in a burglary.

Ironically, most of that surveillance ended up disproving the government’s suspicions toward Japanese American communities. The FBI, the Office of Naval Intelligence, and even a White House-commissioned investigation all agreed that there was little risk of any Japanese American “fifth column” rising up to sabotage the United States from within, and advised against mass incarceration. But despite this exonerating evidence, most key intelligence figures still harbored doubts about the loyalty of the “enemy alien” Issei.

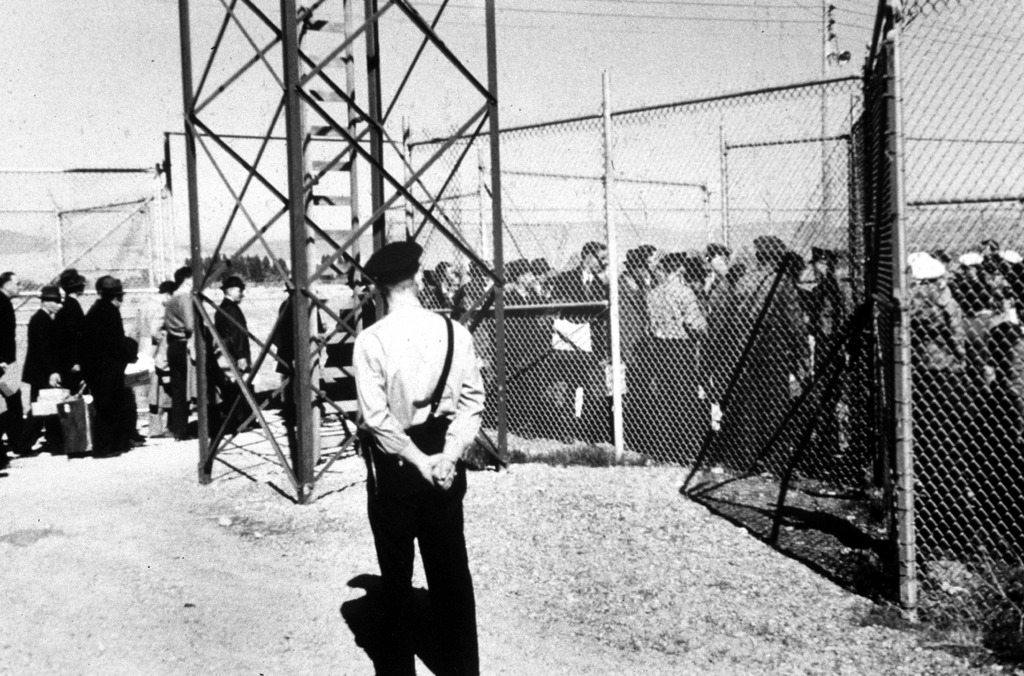

With the authority of the Alien Enemies Act and a presidential proclamation behind them, government officials eventually arrested nearly 9,000 Japanese immigrants, in addition to 11,500 German and 3,000 Italian detainees. Caught in the web of the “Alien Enemy Control Program,” these prisoners were held in isolated Army and Justice Department-run internment camps for the duration of the war, or “released” to one of the ten War Relocation Authority concentration camps. But, as we know today, it didn’t end with the “selective” internment of supposed enemy aliens. This initial roundup in the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor proved to be a trial run for the full-scale removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast over the spring and summer of 1942.

The WWII application of the Alien Enemies Act shows the dangers of giving our government unchecked power to police loyalty and belonging — and how quickly that power can be weaponized against a maligned and marginalized community during times of war and political unrest. Trump’s threat to revive this xenophobic piece of legislation is indeed alarming (and very much on brand). But surveilling and criminalizing immigrants, people of color, and political dissidents is a thoroughly, depressingly bipartisan affair, from COINTELPRO to post-9/11 Muslim registries and the Patriot Act to a sprawling immigrant detention network that has been well fed by multiple administrations on both sides of the aisle.

If this history teaches us anything, it should be the devastating consequences of allowing fear and xenophobia to shape our national policies, and the importance of resisting the resurgence of laws like the Alien Enemies Act.

—

Adapted from Kelli Y. Nakamura’s Densho Encyclopedia article on the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 and “Of Spies and G-Men: How the U.S. Government Turned Japanese Americans into Enemies of the State,” previously published on the Densho Catalyst.

[Header: New arrivals entering the Department of Justice internment camp at Fort Missoula, Montana c. 1942. Courtesy of the K. Ross Toole Archives, University of Montana at Missoula.