October 5, 2017

Stereotypes of archivists as bespectacled introverts navigating unending caverns of file cabinets and stacks are largely exaggerated. But it’s true that, as a lot, we generally enjoy our quiet time and relative introversion. That said, our staff trip to the 2017 Society for American Archivists Conference in Portland, Oregon was both a delightful change of pace and, even more importantly, a powerful catalyst for reflection on goals and strategies for Densho’s own archival practices.

Stepping out of the comfort of our cozy processing room, we found ourselves positioned in the center of multiple dialogues and debates surrounding issues of access, agency, and outreach in archives and cultural repositories. While many panelists and conference-goers posed questions about subjectivity, relativism and questionable representation, one important question was largely avoided: Who owns archival materials — is it the archive or the communities that archival materials represent and were sourced from?

Sessions like “Human Rights in Archives” made it clear that there are some efforts to fairly represent and advocate for the cultural groups whose materials are held in collections. At the same time, there are too few models that demonstrate how to do so in a manner that both respects and includes said groups. In sharing some of Densho’s archival methodologies, we hope to model one way to preserve critical narratives in an effective, respectful, and impactful manner.

What Makes Densho Unique

As a preface to the following discussion, an understanding of the nature of our organization is paramount. Densho virtually hosts a significant amount of historical and archival materials surrounding the Japanese American experience before, during, and after the issuance of Executive Order 9066. Unlike traditional archival repositories, we are a cultural institution in which the preservation of the stories and lessons contained within material records are of the utmost importance. We are also unique in that one of our main goals is to provide a platform that allows individuals and marginalized groups to present their own materials.

Densho’s archival records exist alongside longstanding partnerships with our community, the creation of educational materials, social media outreach that engages current political debates, close relationships with scholars, and public events. We exist to empower, inspire, and help share the voices of the underrepresented. As a result, we depend upon relationships of trust, reciprocity, and respect with the community in which we work. While this is a complex process that we are continually learning from, listed below are a few underlying tenets of our approach, or, what I have come to think of as our “Community Model”.

Location Matters

When attempting to build a house, one must truly begin at the bedrock. Having our physical office located in the outskirts of the historic Seattle Nihonmachi grants our staff the ability to become inspired and involved with some of the locations from which we have related collections. Many of our staff members have personal, family ties to the area.

This location grants us the ability to interact with the strong Japanese American community in Seattle. Additionally, we gain the opportunity for staff and volunteers to have personal connections with the legacies that we help preserve. Sharing these spaces and stories adds a deep level of intimacy and commitment to the handling of a collection. Furthermore, it opens the doors to the cultivation of strong partnerships with like-minded peers and institutions who might possess an entirely different set of expertise.

Being able to work with long-standing institutional pillars of the Asian American community such as the Wing Luke Museum, Nisei Veterans Committee, and the Japanese Cultural & Community Center of Washington grants us tools, resources, and audiences that we would struggle to attain singlehandedly. Lastly, with our historically diverse neighborhood becoming increasingly threatened by various factors, the decision to locate and keep our physical collection in an area of relevance to our materials sends a powerful statement to both those who would participate in the erasure of our local community’s rich history and those who so actively help in its preservation.

Process and Access

Staying economically and physically grounded in an area also impacts how we receive collections. More often than not, potential donors find us, referred from either surrounding local institutions or other individuals who have worked with us to preserve their own family’s personal history. There is something truly special and powerful about being able to show a donor the actual room that their heirlooms were digitized in. It is also extremely helpful to have a network of peers at hand who can assist in identifying unknown aspects of a collection under review.

The narratives we preserve are undeniably part of a living history. We see this as much in the stories we capture in oral histories as in the current events unfurling around us. And because we are deeply engaged with our community, we are constantly reminded that we don’t own this living history so much as help preserve and make it available for the greater good. This belief guided our decision to make all of our materials available for free in our online Digital Repository and, when possible, to allow for Creative Commons licensing for non-commercial usage of those archival materials. By the same token, we respect our narrators’ wishes when they want us to redact parts of their oral histories or sensitive information from their donated archival materials.

Being a repository for a marginalized group’s story and identity is an inherent act of discursive power, and we, as an organization, gain and retain the trust of those whom we represent by maintaining a constant feedback loop of accountability and flexibility. With this in mind, we must stay constant in our resolve to value and include the donor and community’s wishes in our decision making process.

Tools for Engagement

Giving up the proverbial “reins” in the service of fostering a sense of trust and integrity within your community requires a platform that affords others the chance to actively participate and engage with the materials they are represented by. For that reason, a portion of our effort at Densho goes to the creation and maintenance of a publicly accessible, open-source software solution that we utilize for our digitization work. Importantly, we freely provide this tool to other cultural institutions looking to enter the world of digitization whilst avoiding the prohibitive costs of many archival software platforms.

Correspondingly, we actively encourage feedback and participation in the development and analysis of our tools, the majority of which are found here. The decision to build our digitization system based on the Git model was made out of a desire to ensure free, continual access to archival tools. This open access ethos is necessary for sustainable support of groups for whom access to funding is never a guarantee. A willingness to encourage, enable, and even train your surrounding peers in the collection process makes for an enjoyable and meaningful engagement with the materials one holds and creates.

We are always learning and evolving, but we keep three beliefs at the center of our archival practices: First, a repository or institution focused on the empowerment of its subject should have the simple yet irresolute goal of sharing. Second, everyone has the capacity to learn, participate, and grow through interaction with primary source materials. And, last but not least, we will continually strive to respect and amplify the voices of the community represented in our collections.

While our collections process is unusual for our field, we hope that the model we have developed for prioritizing community and individual stakeholders serves as an inspiration for others.

—

By Cameron Johnson, Densho Assistant Digital Archivist

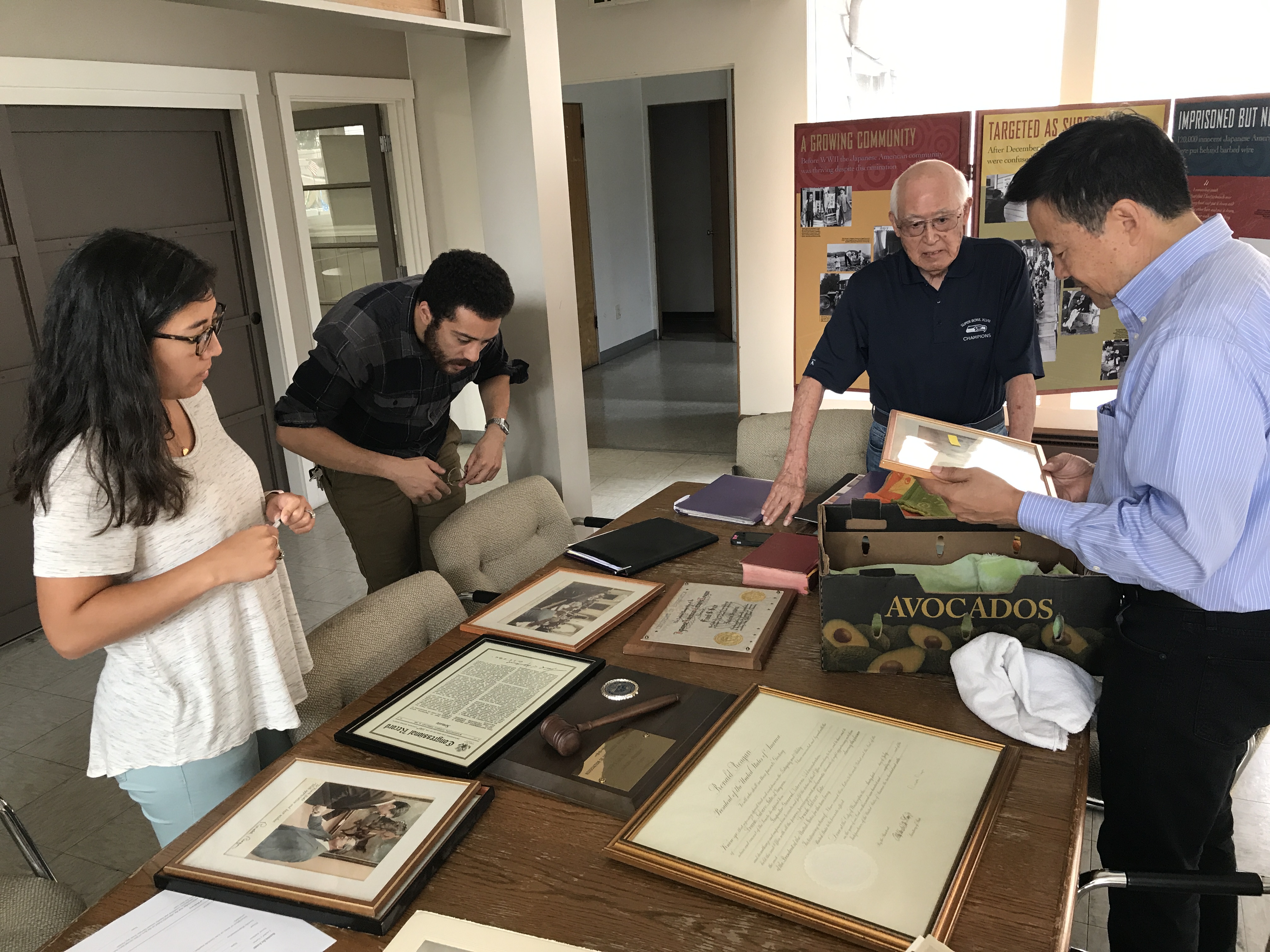

[Header photo: Densho staff members Caitlin Oiye Coon, Cameron Johnson, and Tom Ikeda look over a box of historical materials with Frank Sato on the morning of his oral history interview.]