July 31, 2025

School may not be in session, but there are plenty of lessons to learn and stories to share outside of the classroom! Densho Education & Public Programs Manager Courtney Wai teamed up with Content Director Brian Niiya on this summer reading list to share with the little bookworms and history buffs in your life. Read their reviews of several recently published children’s books that touch on the history of Japanese American WWII incarceration.

Love Grows Here

Story by Chloe Ito Ward, illustrated by Violet Kim

Albert Whitman & Company

Brian Niiya (BN): Brightly illustrated children’s picture book centering on Aiko, a young girl, who is upset by a racist encounter while at an outdoor market with her grandmother. Her grandmother’s friend tells her about her wartime incarceration when she was about the same age. Learning that fear and hate drive such racism, Aiko acts to spread love and tolerance. While the incarceration story is not addressed as directly as many other picture books, this is an appealing book that explores the root causes of the hate that leads to such actions and suggests one way—albeit a simplistic one—to combat it.

Courtney Wai (CW): This powerful yet gentle children’s book introduces young readers to racism and xenophobia in a developmentally appropriate way while reminding them that nobody is too young to take action for justice. Through warm storytelling and joyful illustrations, it uplifts contemporary Japanese American life—showing community, resilience, and cultural pride. Violet Kim’s illustrations bring love and depth to the story, beautifully complementing the story.

The book briefly introduces the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, but it doesn’t center this history as their defining story. Instead, it’s presented as one part of a larger narrative of the Japanese American experience, helping young readers understand the past without being overwhelmed by it. To me, this approach honors the legacy of incarceration while making space for the joy, resistance, and everyday life that continue across generations.

I also love that Japanese words are included authentically in the text without italics. This subtle but powerful choice avoids “othering” the Japanese language and instead affirms the way Japanese Americans live between languages and cultures. The glossary at the back, with its charming illustrations and clear definitions, is a lovely touch that invites readers to learn and connect more deeply with the story.

Michi Challenges History: From Farm Girl to Costume Designer to Relentless Seeker of the Truth: The Life of Michi Nishiura Weglyn

Ken Mochizuki

Norton Young Readers

CW: This biography of Michi Nishiura Weglyn offers a compelling overview of Japanese American incarceration through the life of one remarkable woman. I’ll let Brian weigh in on the finer points of historical accuracy—but as an educator, I see this as a valuable resource for older students. While the tone may feel a bit dry for some readers ages 13-18, it provides a clear and comprehensive introduction to incarceration history by situating it within the broader arc of Michi’s life—before, during, and long after camp.

What makes this book especially powerful is how it uses Michi’s redress work to illuminate the wide range of incarceration experiences that often go untold. Through her research and advocacy, readers can learn not only about her personal story, but about draft resisters, Japanese Latin Americans, and the many different fights for justice after World War II. The book also doesn’t shy away from the internal tensions within the Japanese American community—how trauma, shame, and isolation led many to remain silent, and how the push for redress wasn’t always a unified path. For middle to high school students ready to grapple with what justice really looks like, the book’s honest depiction of disagreement and healing within the Japanese American community opens up meaningful conversations. Michi’s life shows how, with persistence and community support, one person can help bring a buried history into the light.

BN: Thorough and mostly engaging biography of fashion designer turned crusading author Michi Nishiura Weglyn that is really two different stories. The bulk of the book covers Weglyn’s Nisei life, starting with a typical Nisei farmgirl upbringing in California interrupted by her wartime incarceration that was a turning point in her life. But from there, her life takes an unconventional path that leads her becoming a leading New York fashion designer for stage and television, and marriage to a Holocaust survivor to eventually authoring the hugely influential book Years of Infamy. The second story is really that of the wartime incarceration, through chapters that summarize the main arguments of Weglyn’s book. Though some of the latter gets a little dry, the main storyline is unusual and inspiring and illustrated with many images from Weglyn’s estate.

There are a handful of small historical errors, but nothing too serious.

Pearl

Story by Sherri L. Smith, illustrated by Christine Norrie

Graphix

BN: Compelling and beautifully illustrated story of a young Japanese American teenager growing up in prewar Hawai`i who, due to unforeseen circumstances, ends up trapped in Japan with relatives when war between Japan and the US breaks out, setting into motion a chain of events that upend her life. Throughout, she draws strength and inspiration from the words of her great-grandmother, a former pearl diver whose own life was similarly upended decades before.

Apparently based on the memoir of writer Rahna Reiko Rizzuto—a friend of Smith’s and the author of two earlier novels that include camp storylines—the book badly needs an author’s note that provides historical context for the events in the story, especially given a number of recent scholarly works that have filled in the fascinating story of Nisei trapped in Japan during World War II. There are also a couple of significant historical implausibilities that require some explanation. But historical issues aside, this is a handsome and moving story.

CW: Pearl tells the story of Amy, a Japanese American teenager from Hawai`i who finds herself stranded in Hiroshima after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Inspired by real events and historical figures, this work of fiction captures the weight of war through Amy’s eyes as she navigates questions of identity, loyalty, and survival. As Brian notes, there are a few historical accuracy issues—but as an educator, I appreciate how this story invites students to explore the personal and political complexities of the time, while making space for empathy, reflection, and deep discussion. Though listed as a middle-grade book, the layered themes—grief, cultural identity, and intergenerational trauma—make it especially well-suited for high school readers, who are ready to wrestle with ambiguity, question dominant narratives, and consider how history shapes the present.

The illustrations are stunning—limited to a palette of blues, whites, and blacks—but incredibly effective. Full-page scenes depicting violence and trauma are especially powerful, creating emotional weight through visual storytelling. Amy’s struggle to understand what it means to be Japanese, American, and Japanese American is messy and real, shaped by historical events far beyond her control. I loved how the theme of “ikinokoru”—“you must survive”—runs throughout the story, grounding Amy in moments of fear and reminding readers of the resilience that carries her forward.

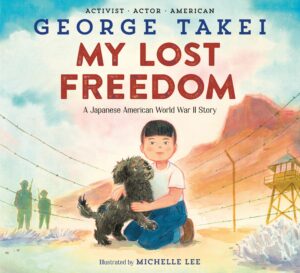

My Lost Freedom: A Japanese American World War II Story

Story by George Takei, illustrated by Michelle Lee

Crown Books for Young Readers

CW: My Lost Freedom is a rich, accessible introduction to Japanese American incarceration during World War II. Although this book is geared towards upper elementary children, I could see how this could be a great introductory text on the incarceration of Japanese Americans for even middle and high school students, as it covers a wide range of topics with clarity.

Told from Takei’s perspective as a young child, the story blends childlike wonder with deep emotion—memories of first snowball fights and a beloved family pet are layered alongside the fear and confusion of life in camp. Through his eyes, readers see how his mother created a sense of home and his father built community, even under unjust conditions.

Takei writes chronologically from his parents’ immigration to post-camp resettlement, weaving in critical historical moments like Pearl Harbor, the loyalty questionnaire, the 442nd, and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Illustrated primary sources—radio clips, newspapers, and government documents—help contextualize key events and provide a potential springboard for further exploration. Though the book’s introduction doesn’t dwell on Takei’s pre-Pearl Harbor life, educators and families can easily supplement that piece. Additional photos and context at the end offer helpful background for readers.

Michelle Lee’s illustrations are both beautiful and deeply researched, capturing moments of both joy and injustice. The contrast between Takei reciting the Pledge of Allegiance while staring at a sentry tower says it all—this is a story of resilience, resistance, and love, even in the face of injustice and incarceration.

BN: Handsomely illustrated incarceration memoir for young children (ages 6-9) by George Takei that starts with the attack on Pearl Harbor and ends with the Takei family’s return to Los Angeles. Most of the story takes place in Santa Anita, Rohwer, and Tule Lake, as told from the point of view of a child. An Author’s Note at the end of the book fills in pre- and post-war details on the Takei family and ends with the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which resulted in a government apology and monetary redress. Michelle Lee’s watercolor paintings beautifully illustrate Takei’s story and are a little reminiscent of the camp paintings of Kango Takamura.

While a good introduction to the story for young readers, the text is marred by a series of factual errors—for example, stating that “[e]ach family was assigned a horse stall to sleep in” when this was true for fewer than half of the incarcerees at Santa Anita, mixing up the timeline on the “loyalty questionnaire,” and repeating the common misconception that half of incarcerated Japanese Americans were children. These and a few other inaccuracies, though not egregious, were wholly avoidable and highlight the need for books like this to be reviewed by experts. Keep an eye out for a forthcoming Densho Resource Guide article on this book for more details.

—

By Courtney Wai, Densho Education and Public Programs Manager, and Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

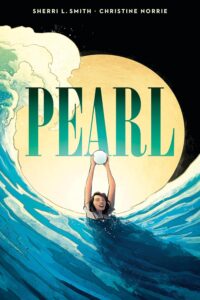

[Header: Masako Takahashi sitting at a desk reading a book, c. 1950s. Courtesy of the Takahashi Family, Densho.]