April 4, 2017

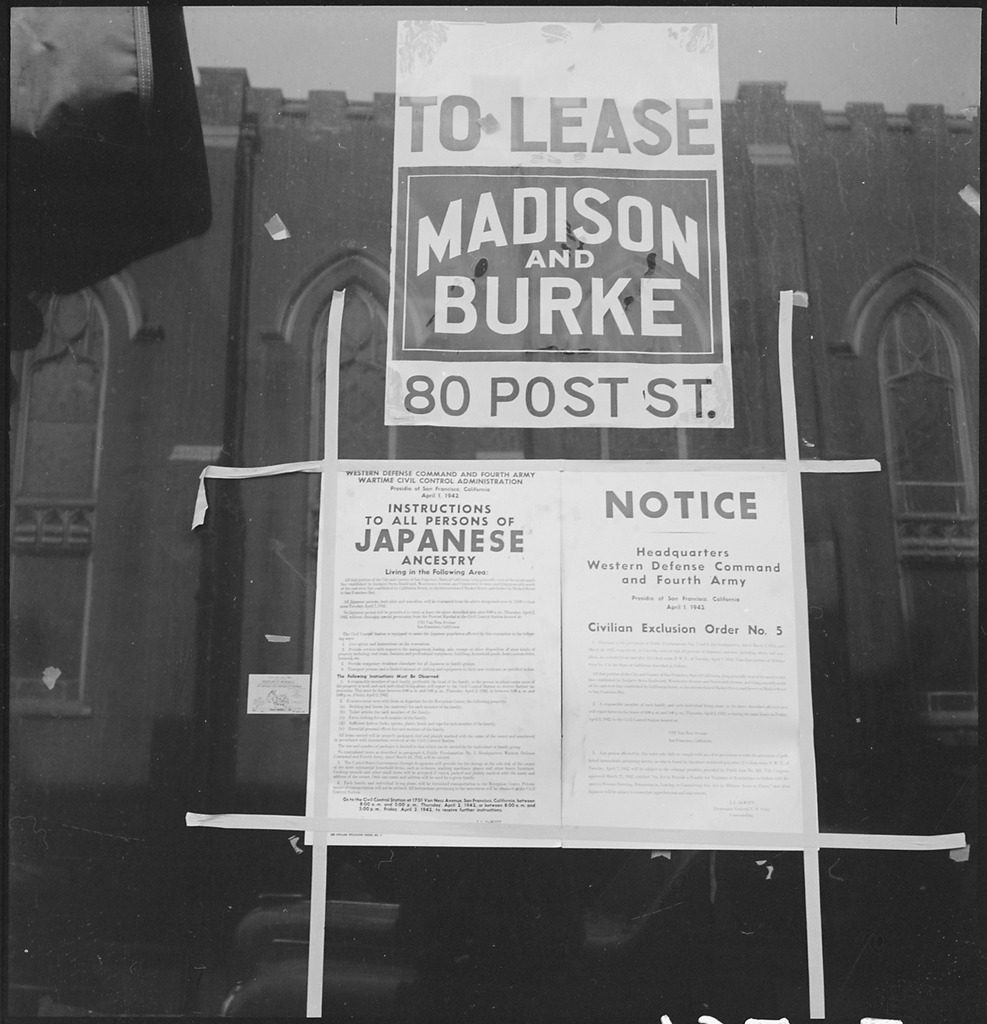

These were just some of the many turmoils Japanese Americans faced 75 years ago this spring. As civilian exclusion orders were posted across West Coast cities, Japanese Americans learned they had a week to ten days to pack up their lives and report for indefinite incarceration.

Despite decades of exclusionary laws and policies intended to keep Japanese Americans from thriving in America, first generation Issei had worked for decades to establish themselves and raise families here. Many were beginning to prosper in agriculture, the fishing industry, and as small business owners. Some were even able to send money to relatives in Japan. But beginning in the summer of 1941, some bank accounts were frozen. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Executive Order 9066 would mean trading these hard-earned lives for barracks and barbed wire.

While it’s impossible to quantify the enormous toll that death, injury, psychological trauma, and loss of dignity took on the victims of World War II incarceration, calculating economic losses has also been a challenge. For decades the losses were estimated to be $400 million, but Densho Content Director Brian Niiya notes that, “though oft repeated, Mike Masaoka later copped to making up the figure on the spot while testifying before Congress during hearings for what would become the Evacuation Claims Act.” Better informed calculations now put the sum at somewhere between $1-3 billion (not adjusted for inflation), but there is no way to be certain of the total figure. [1]

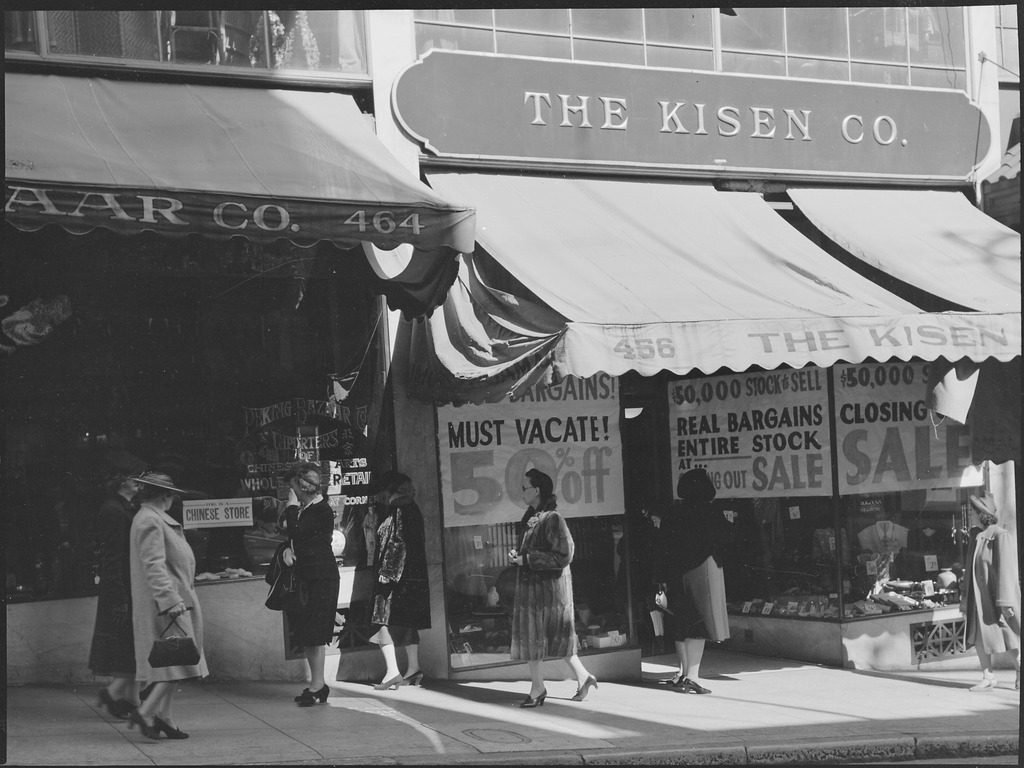

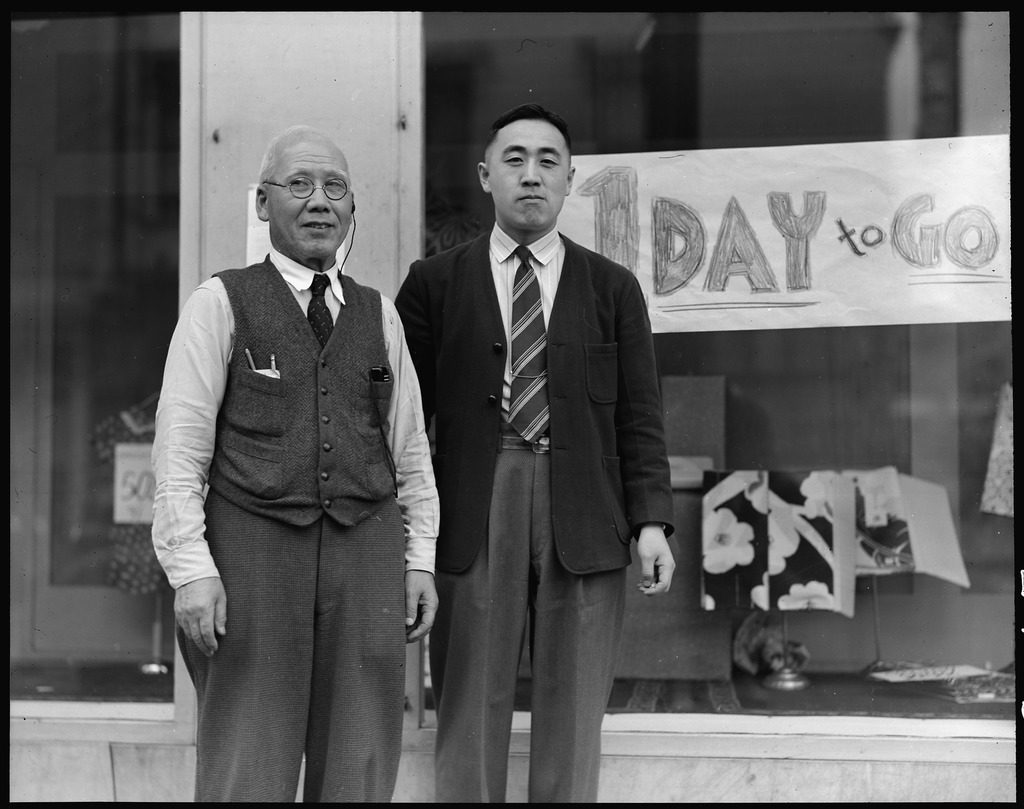

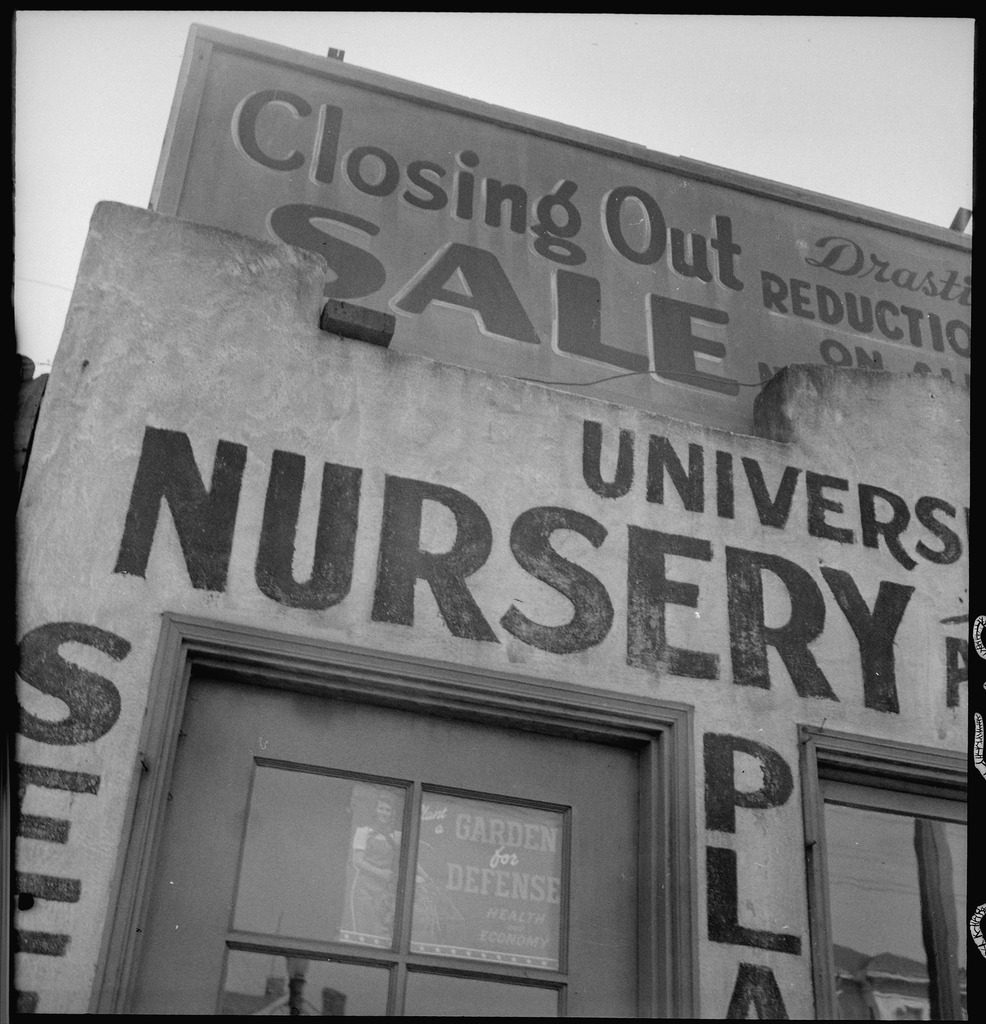

While the economic toll will never be fully known, images and anecdotes suggest the enormity of the property losses, and the personal suffering those losses entailed.

On March 6, 1942 The Seattle Times reported that some Japanese Americans were

“already are conducting ‘removal sales,’ and many complain that they are being annoyed by white competitors, who want to buy the Japanese owner’s stock at 5 or 10 cents on the dollar, now that the Japanese are faced with evacuation. The Japanese know not at what time the government will order them to leave Seattle immediately. Neither do they know how long they will have to dispose of their stocks.”

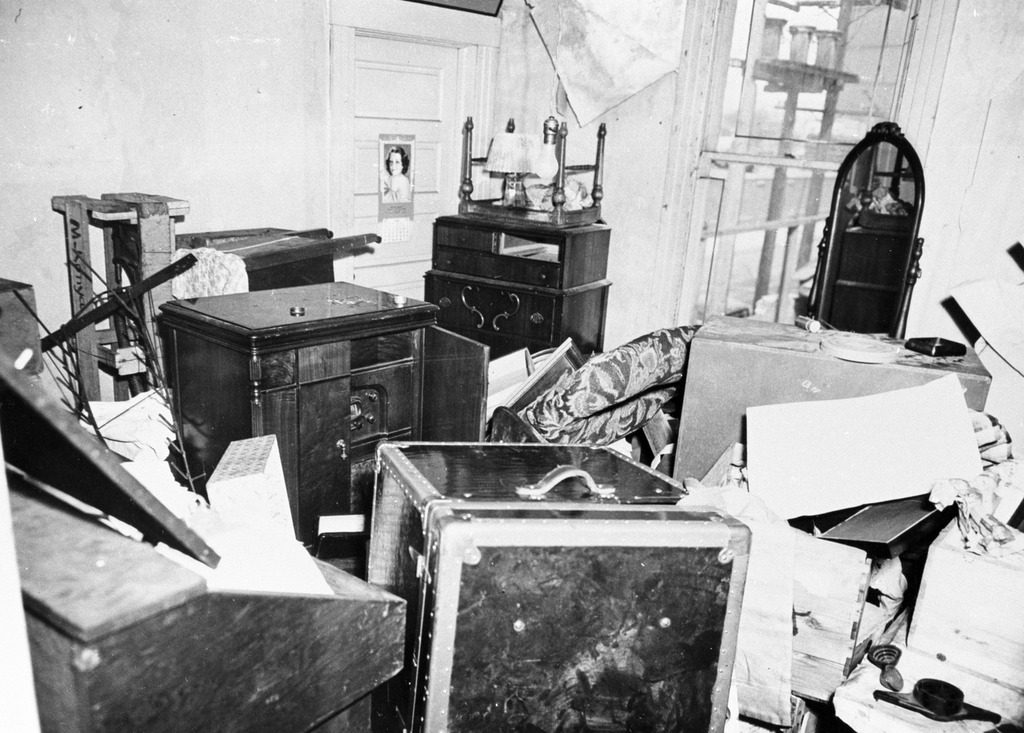

In an interview with Densho, Frank Sumida recalled his father losing his business:

“He lost a ten thousand dollar restaurant. Never compensated. Not a penny.…And the minute we went in camp, they just go right in there and steal everything. They won’t buy it. They knew we were going into camp, so why buy it when you could get it free? And that’s what they did. You know, when I think about that restaurant, it had stainless steel in the kitchen. All the working table and everything were custom made. And we had a small walk-in freezer. It’s unheard of. And then even the dishwashing rack, huh? Not tin, stainless. It was a pretty, pretty fancy restaurant.”

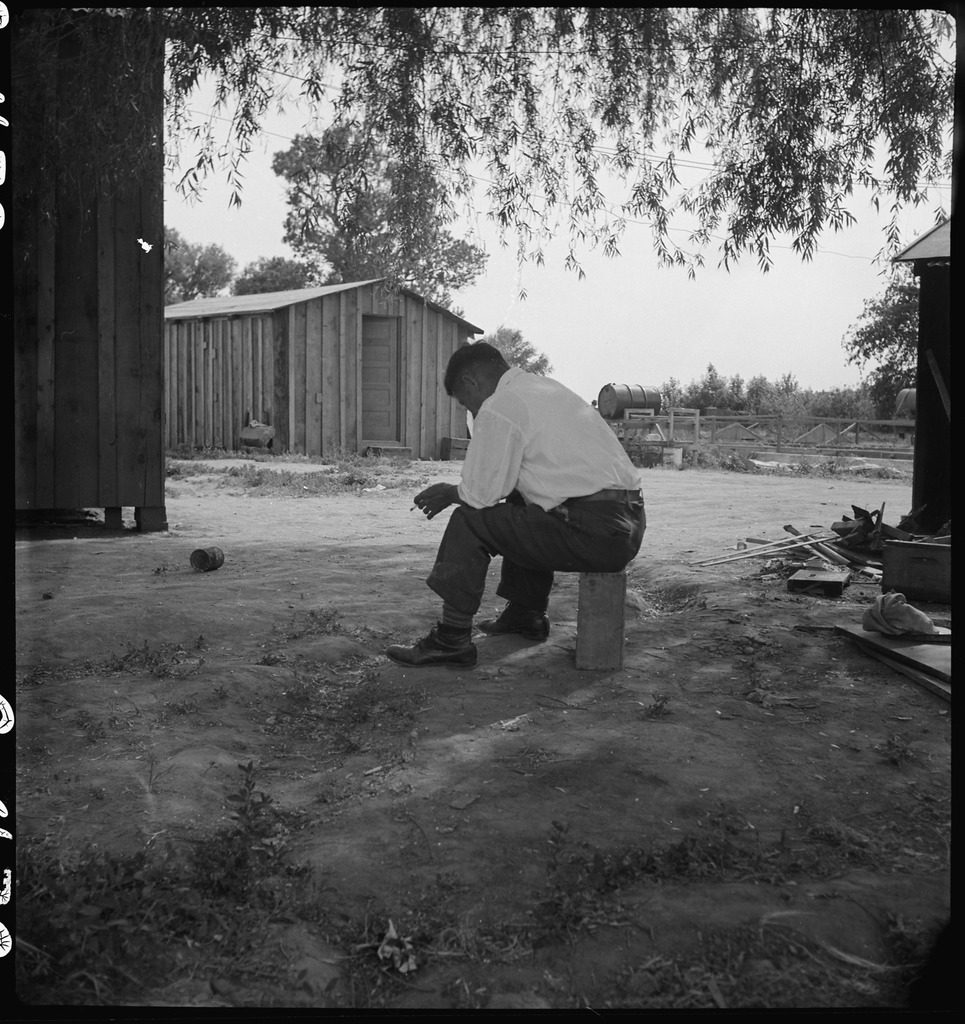

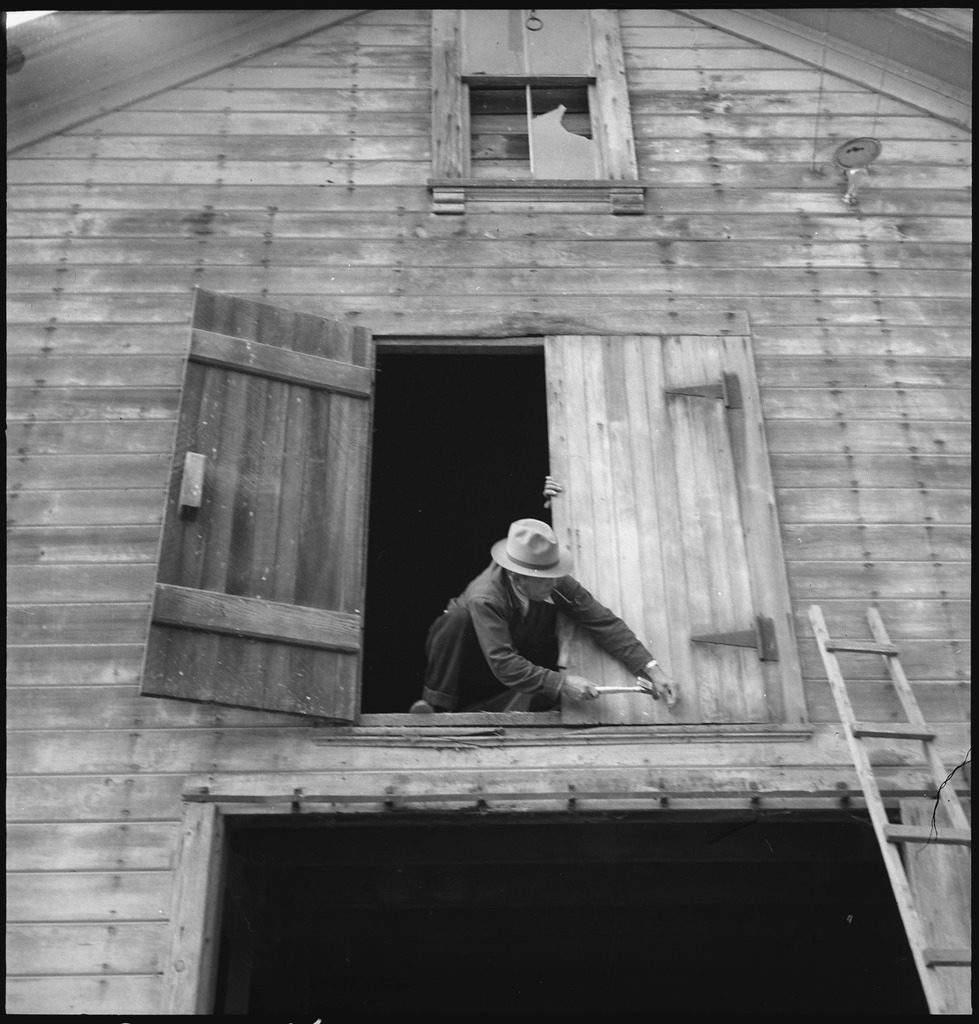

Japanese American farmers were also hit hard by their forced incarceration. And their losses translated into gains for many white investors. In 1942, the managing secretary of the Western Growers Protective Association “reported that considerable profits were realized by the growers and the shippers because of the Japanese removal.” [3]

Yoshimi Matsuura‘s family had to sell their vineyards for a total of $23/acre, instead of the $200/acre they would have netted if they had been allowed to stay and harvest the grapes themselves. And Mitsuko Hashiguchi recalled what happened after Western Farm Incorporated promised to run her family farm:

“They said they will harvest everything and take care of it for us and will send us the money when they get it all harvested and all this, things that go with it. And I think the government must have stepped in later because I heard that’s all they did was harvest just the strawberries and peas out of the field and whatever they did with it… they must have sold it or whatever they did. After that nothing was done to the field. They did not touch it again or do anything out there, and they ransacked all the houses.”

And Harvey Watanabe recalled coming home to find stolen and vandalized property on his family’s farm:

“It was leased. The farm was leased. But the lessee just stole everything. Didn’t continue to farm and then left the house vacant so then the vandals got in and got rid, vandalized all of our personal property that was stored in the attic of the house. All the photographs and everything were all… gone. The lessee had stripped it of all the appliances and everything. Plumbing and appliances were stripped out of the house. The horses were sold. The farm implements were sold.”

For the first several months of “evacuation” it was unclear which agency would be responsible for safeguarding Japanese American property. By the time the responsibility was determined to be with the WRA, many had already been forced to leave their property behind. According to historian Sandra Taylor, “Initial losses were compounded by vandalism and the local officials’ indifference to protecting Japanese property.” [3]

When Densho interviewed Peggy Nishimura Bain in 2004, she was still (understandably) upset about how she and her family lost their property:

“I keep dreaming about that place all the time, because I figure that was our home. And I always felt that we should have been able to come back to it. Of course, the government did give compensation, a small amount. You could, you put in a claim for what you lost during the war. I think, if I remember correctly, I got a thousand dollars for things that I lost, but that is so, such a small amount for the loss that I had, because I lost everything. I left my things with my neighbors, left all the good things, and, ‘course, they were all gone when I came back. And they said, ‘Well, I guess it got stolen or something. We don’t know what happened to it.’ That’s the case of many, many other cases that, that left things in care of other people or their neighbors or something, and they don’t know what happened to it.”

…

In 1948 President Truman signed the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act into law, with the intent that it would provide some compensation for the economic loss suffered during WWII. However, the requirements for proving loss and other red tape rendered the program largely ineffective. As historian Greg Robinson explains in the Densho Encyclopedia:

“The former inmates were required to provide sworn testimony and to produce receipts and other proofs of their losses. If their claim amounted to over $2,500, they were required in effect to sue the government for damages, and await fresh appropriation of funds to pay claims. The Justice Department strongly contested each claim, using a legalistic definition of what could be counted as a ‘loss.'”

Decades later, the Redress Movement would succeed in achieving some monetary restitution to account for some of these losses. In signing the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which awarded $20,000 to each living survivor of incarceration, President Reagan acknowledged the Act was only a fraction of America’s moral and financial debt to Japanese Americans:

“No payment can make up for those lost years,” he said, “so what is most important in this bill has less to do with property than with honor for here we admit a wrong.”

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Manager

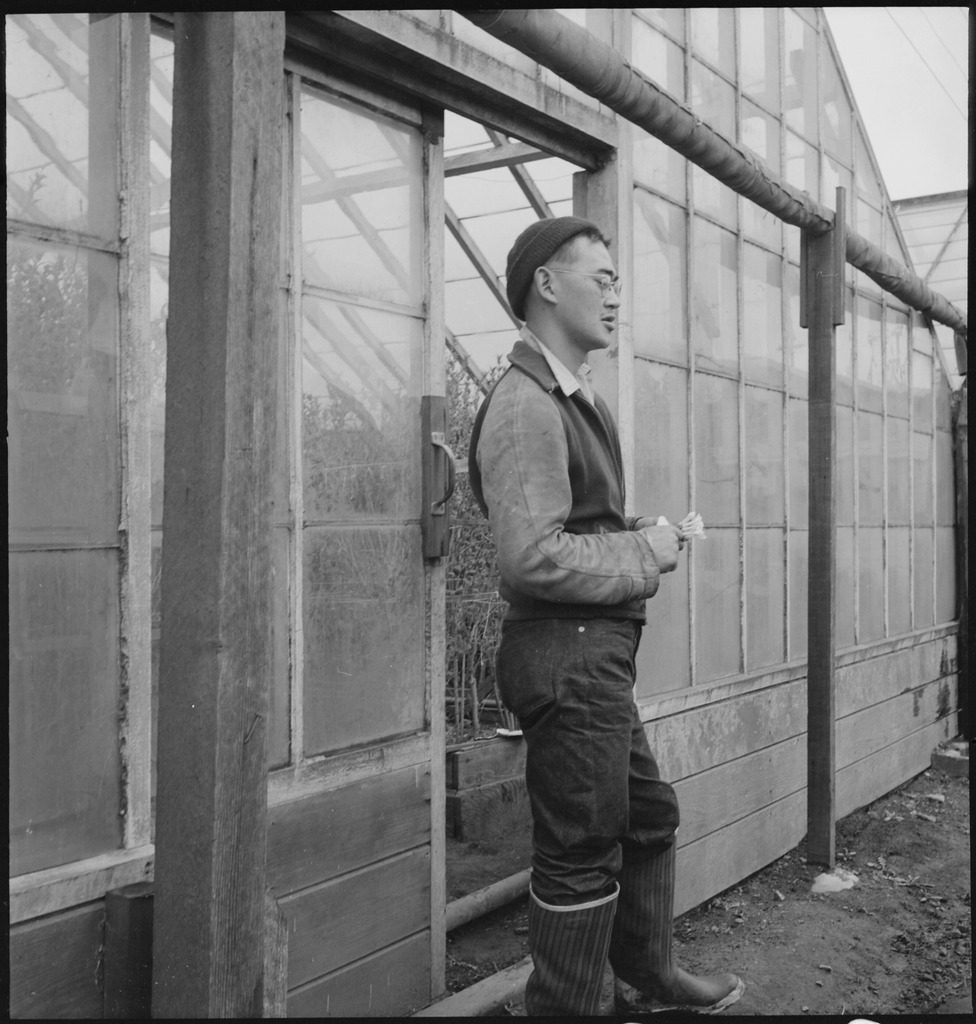

[Header photo: Original caption: Sacramento, California. Preparations are being made for evacuation two days hence of all residents of Japanese ancestry from this city. May 11, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]

1. Taylor, Sandra C. “Evacuation and Economic Loss: Questions and Perspectives.” In Daniels, Roger, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H. L. Kitano, eds. Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1986. Revised edition. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991. 163-67, p. 166.

2. Okihiro, Gary Y., and David Drummond. “The Concentration Camps and Japanese Economic Losses in California Agriculture, 1900-1942.” In Daniels, Roger, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H. L. Kitano, eds. Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1986. Revised edition. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991. 168-75, p. 171

3. Taylor, Ibid., p. 163