January 20, 2016

Born in Japan, Sasaski immigrated to the United States in 1919. Shortly after his 1939 graduation from the University of Washington, he was incarcerated at the Minidoka concentration camp for the duration of World War II. After the war, he relocated to New York where he worked for Standard & Poor’s financial institution before relocating to Denver and, eventually, Seattle. Sasaki is perhaps best know for his work on the Seattle Plan for redress in the early 1970s, but for 20 years prior to that he waged an eloquent, persistent, and, at times, acerbic campaign to eliminate the pejorative use of the word “Jap” in print media and to have the term listed more appropriately in dictionaries. Sasaki’s personal dedication to the cause was remarkable but the support of the Japanese American Citizens League and other activists were critical to his success. Here are some highlights from that campaign.

As early as 1880, the English Oxford dictionary noted “Jap” as a colloquial term of abbreviation. Though it may have started out as a neutral term, it took on increasingly negative connotations as anti-Japanese sentiment grew. It was used as a slur against Japanese immigrants and, later, in reference to Japanese American citizens. Following World War II, the use of the word became even more opprobrious but was still in wide use.

As early as 1880, the English Oxford dictionary noted “Jap” as a colloquial term of abbreviation. Though it may have started out as a neutral term, it took on increasingly negative connotations as anti-Japanese sentiment grew. It was used as a slur against Japanese immigrants and, later, in reference to Japanese American citizens. Following World War II, the use of the word became even more opprobrious but was still in wide use.

Sasaki took note of the prevalence of this disparaging term in print media and decided to take action. He later recalled, “Back in 1952, in cooperation with the Japanese American Citizens League and the New York Local of the American Newspaper Guild, I helped to wage a campaign to eliminate the use of the term ‘Jap’ in the American press. For one year, most of my spare time at home was spent in pushing this effort.”

In a letter to the Executive Committee of the Newspaper Guild of New York, Sasaki requested that Newspaper Guild Executive Committee place “Jap” in the same category as other racial epithets, discouraging use in newspapers and magazines. His arguments included:

- “The term ‘Jap’ is regarded by the Japanese as an epithet of derision. Its use is resented by all Japanese and persons of Japanese ancestry.”

- “The excuse that the term ‘Jap’ is usually used without any derogatory intention is pointless. It frequently has been and is being used with the connotation of contempt. Furthermore, not even a moron would persist in calling a person by any name which that person considered offensive, when at the same time the goodwill and friendship of that person were desired.“

- “The use of the term ‘Jap’ completely nullifies in the eyes of the Japanese all American claims to being the world’s champion of human dignity.”

In February 1952 , the New York Newspaper Guild passed a resolution and sent a letter sent to all New York publishers. But the resolution was not as effective as Sasaki had hoped and “newspapers continued to use the epithet as freely as ever.” Sasaki mounted a letter-writing campaign to the offending papers and organized protests with the help of the New York JACL.

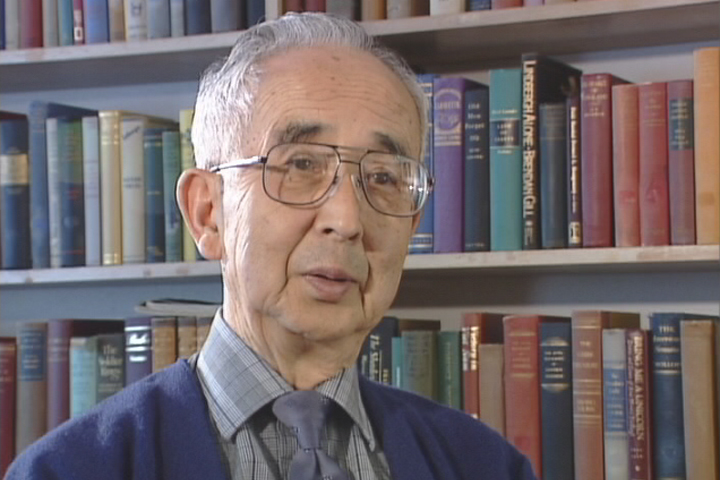

In this Densho interview, Sasaki recalls his efforts to eliminate use of the word “Jap” in print media:

Sasaki continued writing personal letters of protest to any publication that printed the word. As a Pacific Citizen article recounted, “Much of [Sasaki’s] time at home was spent in going over the newspapers, clipping out offending sections and writing letters to editors and publishers.”

Because he was convinced that the media needed a compelling reason to eliminate use of the term, Sasaki tapped into the conservative zeitgeist of his time and incorporated anti-communist rhetoric into his campaign. In a letter to the Guild executive committee he wrote: “The cooperation of the United States and Japan is urgently needed if they are to preserve their independence against Soviet encroachments and propaganda. Since most publishers seem determined to continue an unnecessary source of ill will which the Communists are effectively using against America, I ask that the Newspaper Guild take action to stop this giving aid and comfort to the Soviet Union.”

In 1953, Sasaki resigned from the JACL because he wanted to start a campaign against the dictionary publishers over their definitions of “Jap” but claimed that the JACL was “too timid” to do so at the time.

He continued sending individual letters whenever he encountered the word in the media. In correspondence with Dr. Koto Matsudaira, Permanent Representative to the United Nations from Japan, Sasaki criticized the Prime Minister’s televised comment that he “did not find the term ‘Jap’ to be offensive.” He wrote, “No other racial or national group in the United States at present suffers from the indignity of having itself referred to in the American press by means of derisive epithets. Only the Japanese continue to be singled out for this kind of public humiliation and insult.”

In 1958, Sasaki rejoined the JACL and wrote much of the correspondence for a new JACL national campaign against the dictionary companies. In 1962, he authored the JACL booklet How to Attack the Newspaper Use of Jap.

His campaigns were largely successful but in 1973 the issue resurfaced. That year, the Merriam Co. dictionary included the word but failed to indicate that it was a racial slur. Editorial director H.B. Woolf defended the dictionary’s decision saying, “‘Jap’ is not a noun so it’s not deserving of same treatment given to other racial epithets.”

Sasaki who, by that time, had retired and moved back to Seattle, had the help of Dr. Clifford I. Uyeda in a new campaign against the dictionary company. Dr. Clifford I. Uyeda responded to H.B. Woolf: “Whether written or spoken, it is used as a noun. For over two generations on the west coast of the United States, the term ‘Jap’ has been used with hate and contempt directly implied. If your dictionary is to accurately record the definition for ‘Jap,’ it cannot ignore the fact that is has been used, is being used, and is taken by Japanese Americans as a stinging racial epithet.”

Sasaki chimed in, asking Merriam-Webster to pull copies of their 1973 dictionary out of circulation and to add a usage warning. He wrote, “As an organization of loyal Americans whose members have been long-time victims of this kind of callous disregard by certain types of whites, the JACL has no choice except to take strong and determined counter-measures.”

In a speech to the Social Responsibility Round Table of the Washington Library Association, Sasaki lambasted the dictionary: “The Japanese have been a major thorn in the egos of those who want to believe that the white people are mentally and morally superior to all other races…As a result, persons of the Japanese race have repeatedly been singled out for various kinds of heartless cruelty, ill treatment, and insults by certain types of people. The reactions of the editors of G.&C. Merriam Co. are those of a stubbornly stupid bureaucrat who can follow only his narrow interpretation of what he thinks are the ‘rules.‘”

Finally, in 1975 Sasaki and his supporters got what they were looking for. The new edition of the Merriam-Webster dictionary included the annotation: “usu. used disparagingly.” Since then, the term has widely fallen out of use but a survey of online dictionaries shows that the word is treated inconsistently, and often without the gravity and usage warnings it deserves. Read more about the continued use of “Jap” in online dictionaries.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications Manager

The information provided here was gleaned from the Shosuske Sasaki Collection in the Densho Digital Repository. View the collection here.