April 2, 2018

In recent months, an outpouring of stories of sexual harassment, abuse, and assault has sparked long overdue conversations around the prevalence of sexual violence and the policies, attitudes, and silences that uphold it. As descendants of Japanese Americans criminalized during WWII who often use our own families’ stories to warn against the repetition of history, we know well that to understand our present we must reckon with our past. But for too long, the stories we tell have erased the victims and survivors of sexual violence in our own community. It is time we broke that silence.

[Content warning: Rape, sexual abuse, domestic violence]

Over the years, a vast library of historical fiction, textbooks, dissertations, academic journals, children’s books, plays, memoirs, and more have delved into the impacts of Japanese American incarceration on those who lived through it. Much has been said about economic hardship and interrupted dreams and the breakdown of traditional (read: patriarchal) family structures. And while these stories are valuable and necessary, they are incomplete.

Missing from the common narrative of incarceration are the stories we do not wish to hear. Stories that bear witness to the ways victims of institutional harm can become perpetrators of individual violence, the silence and sacrifice demanded of women of color from both within and without their own communities, the toxic symbiosis of rape culture and white supremacy.

Predictably, there are relatively few documented cases of violence against Japanese American women during World War II. The anti-Japanese vitriol unleashed by Pearl Harbor compounded pre-existing impediments to reporting assault and abuse—language barriers, immigration status, racism, sexism, shame, fear. Most Nikkei victims’ only previous contact with police would have been through illegal raids, disappearances of family members, and other abuses of power.

The forced “evacuation” to inland concentration camps, carried out by armed soldiers wearing U.S. Army uniforms, did little to build trust in American authorities as a source of protection. Rumors quickly spread of inmates raped by white guards, of predators lurking outside the latrines at night, of girls’ bodies found mutilated and discarded.

Some of these rumors proved to be untrue—but they nevertheless reflected a pervasive and very real fear of what could, and frequently did happen. As Tamie Tsuchiyama, a Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) researcher, wrote of a rape thought to have occurred in Poston: “Fortunately, this turned out to be a groundless story, but you must realize that the condition was such to produce this kind of rumor and the people believed it.”

For every “groundless story” there were examples of real, tangible violence: A few months before removal, a woman assaulted by men who forced their way into her home posing as FBI agents. Within one month of the opening of Tanforan, three rapes and at least two attempted assaults. In Tulare, a woman attacked in the night and the police unable to find a suspect. Warnings between friends about “wolves” who should “be avoided if possible.” Multiple reports from multiple camps of “girls being molested” and men “peeking in” at women in the showers.

At work and in public spaces like the latrines and the streets between barracks, women were harassed, followed, threatened. At “home,” instances of domestic violence and sexual abuse were often audible in neighboring barracks and became common knowledge around the camp.

The heightened anxiety many women felt as they moved through the camps was survival instinct honed by a lifetime spent navigating a world where such violence is norm not aberration. They experienced incarceration not just as a violation of their civil rights but of their physical safety and bodily autonomy, their freedom of movement constricted not just by barbed wire and high desert but by the constant threat of sexual violence.

Concrete evidence of sexual assault is often obscured in official records. It appears far more often as hints and whispers buried between the lines of letters, journals, and forgotten case files—frequently dismissed as gossip or feminine paranoia. Even progressives like Charles Kikuchi, a social worker known for his civil rights activism and early critiques of the model minority myth, showed a resistance to taking women’s statements seriously. In a section of his diary titled “Rumors Surrounding Sexual Delinquency,” he eavesdrops on two female coworkers discussing an alleged rape and writes it off with a cavalier, “How the rumors can grow!”

These stories are largely retold by men hesitant to pass judgment on their peers—other men who often, as one observer put it, “looked harmless beyond this crime.” There is a certain boys-will-be-boys resignation to the ways of the world. A sense that it is up to women to take the proper precautions to avoid assault.

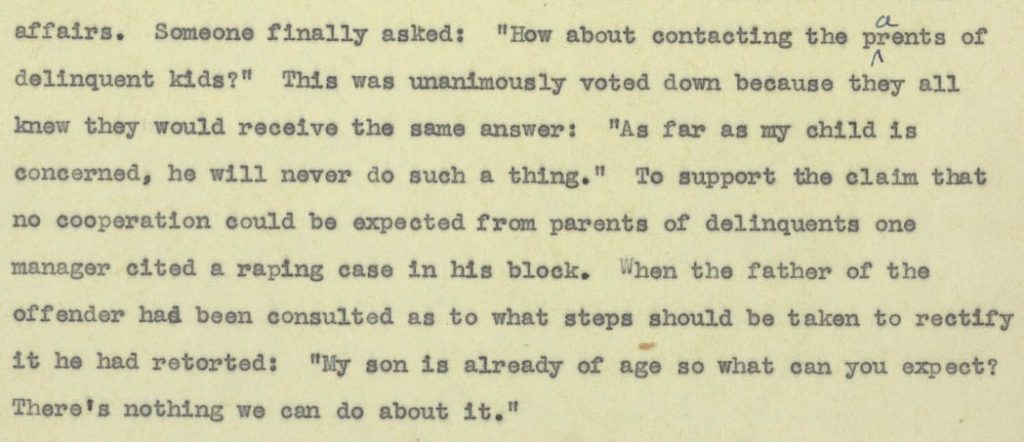

Of course, this reluctance to believe survivors was a reflection of attitudes within the larger community. When a group of young women attending a dance at Camp Shelby were “mauled” by 442nd recruits, one enlistee wrote to the Denson Tribune excusing his friends’ aggressive behavior: “After all, what do you think would happen if a mere 100 girls were pitted against some 400 soldiers?” Meanwhile, in Poston, the father of a rapist casually described the assault as a mere quirk of puberty: “My son is already of an age so what can you expect? There’s nothing we can do about it.” The meeting where the rape was brought up, intended to address gang activity in the camp—including sexual assault—eventually devolved into a critique of teen girls “cut[ting] classes to take walks in the woods with their boyfriends.”

This handwringing over the “loose morals” of the girls in the woods (and other isolated corners of camp hidden away from public view) was a recurring theme. Rather than discuss how to prevent sexual violence, administrators and incarcerated community leaders attempted to prevent sex they viewed as indecent or abnormal. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) treated any sexual activity that took place outside the heteronormative confines of marriage as criminal behavior. Adultery, abortion, pre-marital sex, queer sex, and interracial sex were criminalized alongside rape, incest, and child molestation— opening up victims to punishment for supposed “offenses against chastity.”

Victims who did not conform to these puritanical expectations elicited little sympathy from either their wardens or their fellow prisoners.

The callous response to the 1944 murder of May Tsubouchi is particularly damning.

Tsubouchi, 24, lived with her father in Poston and had recently ended a relationship with a mess hall coworker, Isamu Takahashi, 35. In the two months following the break up, Takahashi repeatedly stalked and threatened Tsubouchi, and neighbors reported hearing multiple “violent quarrels” when he would force his way into her barracks unit “persistent to regain her.” Then, on September 28, 1944, he snuck into her room while she was sleeping and attacked her with a knife. She hovered between life and death in the Poston hospital for two days before succumbing to her injuries. He escaped the camp and, despite the efforts of several search parties, was never found.

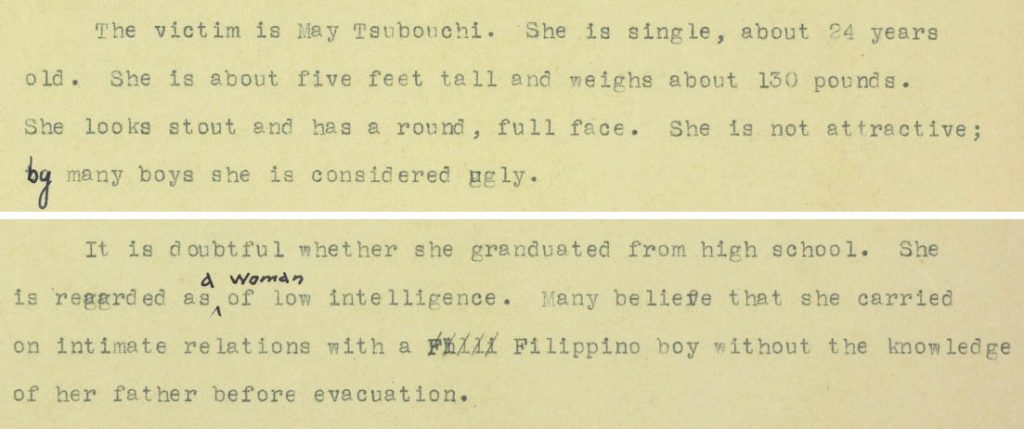

This was a brutal, gruesome murder that should have invoked sympathy and sorrow and a serious look at how her community’s failure to protect this young woman from a violent man’s escalating abuse had facilitated her death. Yet while May was dying in the hospital, her neighbors were calling her a “prostitute” and gossiping about how “she has been sleeping with anybody.” There was no public outcry, no memorial. The camp newsletter attributed her murder to simple “jealousy,” while researcher Richard Nishimoto devoted several pages of his journal to a detailed account of her previous sexual history. He describes her as “stout” and “not attractive,” as if surprised that someone “by many boys… considered ugly” could have inspired such possessive rage. (Nishimoto is, admittedly, one man and perhaps not representative of the entire camp—but judging by the rumors he documented, he was not alone in his opinions.)

The notion that imperfect victims had somehow invited the violence inflicted on them—that the act of being alone with a man connoted consent, and “good girls” knew better than to place themselves in harm’s way—was widespread.

Survivors were silenced with warnings that speaking openly about their assault would result in “a bad reputation” at least, and retaliation against themselves or their families at worst. In one heartbreaking case, a 16-year-old who became pregnant after nearly two years of sexual abuse was pressured by her father to marry her rapist in order to “legitimize” the child and avoid gossip. The girl refused, but the expectation that she sacrifice her body and her freedom just to placate her father’s pride shows exactly why so many victims and survivors chose to remain silent.

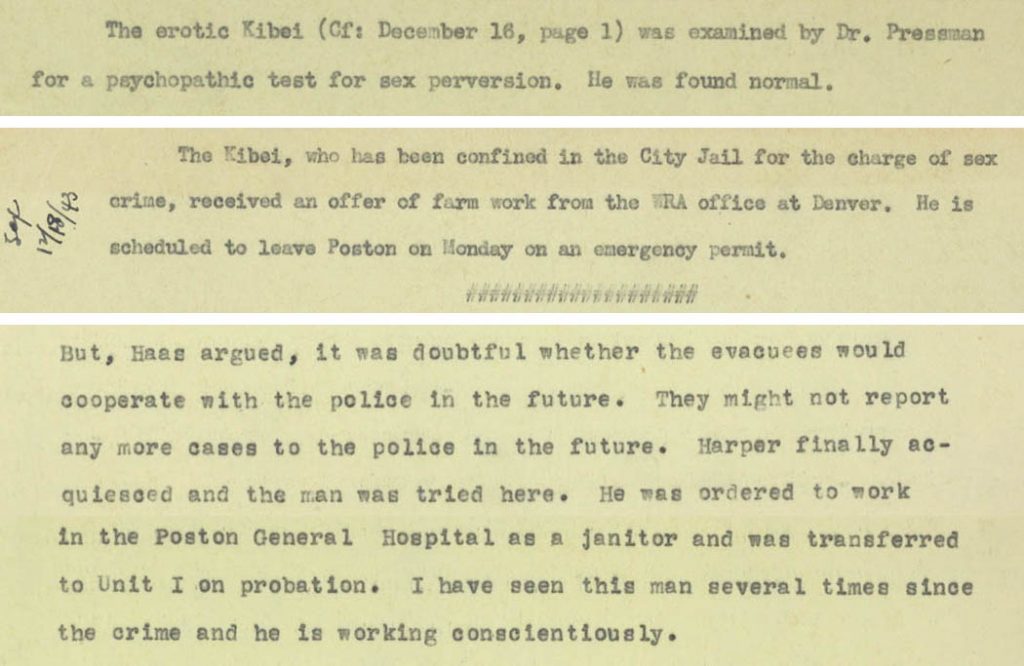

But even if victims did come forward, their abusers were rarely held accountable in any meaningful way. Men who had molested children or committed other offenses were simply transferred to another camp or given a work release, where they could groom new victims unaware of their predatory history.

Perhaps the only case to result in a criminal conviction was an attempted assault of two Nisei women by a Black construction worker in Jerome. In less than a week, the man was in prison and the WRA had begun purging Black employees from the camp’s workforce—an example of “quick justice” indicative not so much of concern for the well-being of Japanese American women as it was of attitudes toward Black men who dared to cross the color line with non-Black women.

In other cases, assaults were ignored or severely mishandled by camp authorities. Two rapes in Tule Lake in the summer of 1944, though apparently widely known among the inmates and referenced in a subsequent FBI report, were never reported “for the reason that the Japanese no longer respect[ed] the police.” This mistrust was well-earned. After the anti-WRA demonstrations that preceded martial law in late 1943, Tule Lake administrators had adopted a “hands-off policy” to sexual violence in order to avoid “another disturbance.” In an earlier, third case of rape, the police proved “unable to take any effective action except to publicize the incident and embarrass the girl and her family.”

Ultimately, the risks associated with reporting sexual abuse or assault—being ostracized as liars, inu, and vengeful ex-girlfriends; retraumatization; retaliation; having their stories coopted to justify increased state surveillance or bolster stereotypes of downtrodden Japanese women in need of white salvation—far outweighed the potential benefits.

Neither was violence against Japanese American women restricted to the camps. Women who left camp during the war to find work or attend school were also vulnerable. Many Nisei resettlers recounted facing sexual harassment from their employers—an experience made all the more frightening by the fact that these women were often doing domestic work that meant entering or even sharing the home of their abuser.

When Japanese American women encountered discrimination in their new homes, it was often tinged with sinister and highly sexualized threats of violence. Poet Mitsuye Yamada describes this dangerous partnership of racism and sexual harassment in “Freedom in Manhattan”:

We were three girls

minding our distance

two thousand miles from home

crouched in darkness behind

the covered bathtub

in the kitchen.

To some boys

we weren’t home

in this cold water flat

one jump from the East River.

No real support system existed for Nisei women who were harassed or assaulted outside the camps. The WRA intentionally steered resettlers toward cities with little to no established Japanese American community in an attempt to strip the Nisei of any cultural ties to Japan. These resettlers were promoted as the vanguard of the “new” Japanese Americans, and their behavior was closely scrutinized for anything that could be construed as unvirtuous or anti-American. There was intense pressure—from both the government and segments of the Nikkei community—to blend in, to assimilate, to become model citizens and ambassadors of goodwill. Japanese American women received a clear, if implicit, message that stories contradicting this cheerful narrative of upward mobility were best kept to themselves.

We may never be able to recreate a clear picture of sexual violence against Japanese American women during World War II. (Or, for that matter, against the femmes, nonbinary folks, and LGBTQ individuals whose presence in the camps has been largely erased from the historical record.) The vast majority of these stories were buried long ago, if they were ever uttered out loud to begin with. But we can recognize the systems and ideologies that have silenced so many victims—and work to change them.

We can expand and complicate our narratives around historical and present day trauma. We can acknowledge the realities of sexual violence—that it is rarely a stranger in a dark alley, that perpetrators often hide behind their public reputation to avoid personal accountability, that yes, all women are impacted in multiple, intersecting ways. We can challenge the misogyny festering in our own communities, and reimagine what “justice” means for victims who are already subject to surveillance, criminalization, and mass incarceration.

These stories are a part of us, whether we care to admit it or not. Ignoring them only enables this violence to continue uninterrupted, while survivors carry the full weight of their trauma alone. The invisibility of abuse, of women, of sex workers, of queer and trans people, is not an accident. Erasure is an intentional act—we must be equally intentional in our efforts to combat it.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator.

Artwork by Kiku Hughes. Kiku is a comics artist living and working in the Seattle area. Her work has been featured in “Beyond: A Queer Sci-Fi and Fantasy Comic Anthology”, “Elements: Comic Anthology by Creators of Color” and Short Box Comics Collection. She is currently working with First Second Books to publish her first graphic novel, about Japanese American incarceration. Funding for Kiku’s work was generously provided by a grant from the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture.

Author’s note: The majority of this information is sourced from the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study field notes of Tamie Tsuchiyama, Richard Nishimoto, Charles Kikuchi, and James Sakoda, accessible at the JERS online archive at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library. (It should be noted that Tsuchiyama—the only Japanese American woman to work for JERS full time—left behind a more extensive, and empathetic, record of sexual violence than her peers.)

Details about the War Relocation Authority’s classification of sex crimes, the women “mauled” by soldiers at Camp Shelby, and the attempted assault in Jerome came from John Howard’s Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow (pp 115 and 133-36). The FBI report referencing unreported rapes in Tule Lake is cited in Part 2 of Barbara Takei’s “Legalizing Detention” on DiscoverNikkei.org. Sexual abuse described in letters to the WRA Solicitor’s Office were discovered by Eric L. Muller. The quoted poem from Mitsuye Yamada appears in Camp Notes. Additional research, guidance, and reminders that the world is not complete trash were contributed by my Densho colleagues Brian Niiya and Natasha Varner.