January 29, 2021

Once a taboo topic, the impacts of WWII incarceration on Japanese Americans who lived through it are well-documented and widely acknowledged today. Donna K. Nagata, a psychology professor at the University of Michigan and the daughter of camp survivors, started studying these impacts in the early 1990s, focusing first on the intergenerational effects felt by the Sansei and then expanding to look at the lived experiences of Nisei like her parents. Her research has provided vital insight into the lasting legacy of WWII incarceration — and how it continues to reverberate in the Japanese American community decades later.

But the question of how the incarceration affects later generations of Japanese Americans, who don’t have a direct connection to the experience, remains largely unanswered. Dr. Nagata recently began investigating just that. She’s in the middle of a new research study on Yonsei perspectives of the WWII incarceration and its influence on their lives.

Dr. Nagata agreed to answer a few of our questions about what inspired the Yonsei Project and what she hopes to learn this time around. Want to help by taking the survey? Anyone over the age of 18 who identifies as a Yonsei (4th generation Japanese American) is invited to participate at bit.ly/YonseiSurvey!

Can you share a little about your personal connection to this history?

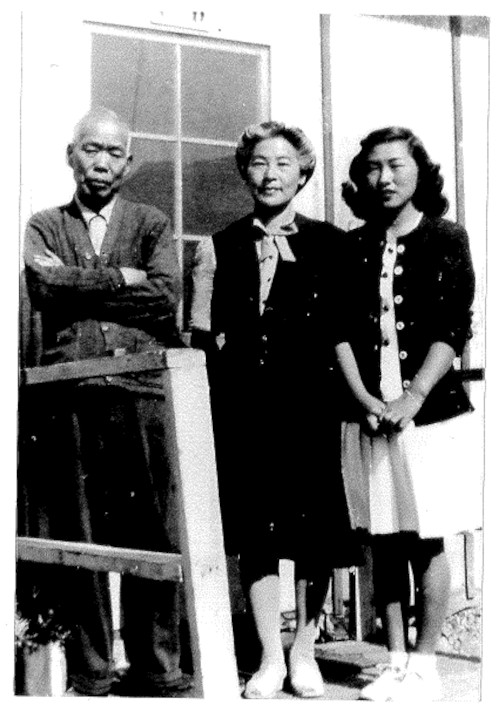

Both sides of my family were incarcerated during the war. My Nisei parents first met in Topaz when they were teenagers, so my very existence is actually linked to this history! Like many Sansei, I also grew up in a family where discussions about the incarceration were pretty much absent and the word “camp” was used only as a vague reference point (‘that was before camp/after camp”; “we knew so-and-so from camp”) or an occasional funny story (“remember when ‘x’ tried to sneak back into the mess hall line to get seconds?”). I sensed that something was being avoided.

In the introduction to the 1993 book I wrote about my Sansei research, I mention a story about finding a jar of small colored shells under my grandmother’s sink when I was young. Excited by the discovery, I asked my grandmother where they came from. She did not answer directly and instead said, “Go ask your mother.” When I went to my mother with the same question, she said, “I made them in camp.” I assumed that “camp” was similar to a Girl Scout camp and enthusiastically asked, “Was it fun?” Her curt response of “Not really” surprised me and let me know that I should not continue the conversation. Interactions like this conveyed that the topic of camp was not something to pursue. Other Sansei shared similarly avoidant conversations in their families as well.

Decades later, I learned about the significance and magnitude of the incarceration through readings and videos. My academic training as a clinical psychologist and researcher also taught me to appreciate the intergenerational dynamics of historical traumas. That knowledge, combined with my personal observations while growing up, led me to this research.

Why do you think it’s important to research the incarceration’s impact on Yonsei?

Investigating potential impacts among the Yonsei is the next step in understanding the long-term effects of the incarceration. My Sansei research explored these impacts on the children of those who were in camp. Today, the question is how might these consequences extend to the grandchildren? When I researched this question among the Sansei generation, most of them were in their late 20’s to late 30s. Many Yonsei are now in that age range, so approximately within the same developmental range, but they have grown up in a very different social context and are much more likely to be multiethnic or multiracial. Their life experiences offer an important and distinctive lens in relation to the incarceration.

In your interview with Hana Maruyama for the first episode of Campu, you said that silence “is a really powerful transmitter of trauma.” As more Japanese Americans of all generations are speaking up about this history and how it’s impacted their lives, do you see any lessening or shifting of that trauma?

I think there has been a progressive shift toward destigmatizing conversations about the incarceration with each generation. While most Nisei kept silent about their experiences, Sansei sensed their pain and advocated for more public recognition of the injustice. The multigenerational redress movement and its success were critical in “opening up” the history. This provided a shared sense of community and conversation that reduced the isolated silence so many Nisei had endured.

All generations now seem more able to engage and speak out about the incarceration as a traumatic historical event. Reducing the silence has been a very important aspect of trauma processing and there are Yonsei, along with Sansei, who continue to bring attention to this part of JA history and issues of social justice.

Have you received any feedback about how participating in your research has impacted people?

The most common response has been that taking the Yonsei survey was “cathartic”! This reaction, in combination with social media comments like “feeling seen,” suggests that perhaps the survey has traction because it resonates with Yonsei by addressing experiences that personally affect them but are not addressed in their day-to-day lives. A similar thing happened when I conducted the Sansei Project years ago.

At the end of their survey, people wrote comments expressing appreciation at seeing research questions that directly touched on incarceration topics and family communications related to the camps that resonated with them. This had a positive impact by affirming that their experiences were “real”, shared by others, and warranted research attention. Hopefully, there will be Yonsei who find the current survey beneficial as well.

Learn more about Dr. Nagata’s research and take the Yonsei Survey at bit.ly/YonseiSurvey

—

Donna Nagata, PhD, is Clinical Science Chair, Director of Clinical Training, and a Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan, and the author of Legacy of Injustice: Exploring the Cross-Generational Impact of the Japanese American Internment. Her research focuses on Asian American mental health; Japanese Americans and the psychosocial consequences of the World War II incarceration and historical trauma; Asian American family processes; intergenerational relations; emotions and distress.