August 4, 2025

Densho Development & Communications Manager Jennifer Noji joined nearly 250 fellow pilgrims in returning to the Minidoka incarceration site to commemorate the past and critically interrogate the present. Jen shares some key takeaways from the 2025 Minidoka Pilgrimage, reflecting on the importance of collective remembrance and storytelling to heal from historical trauma and reckon with legacies of violence.

Last month, I had the honor and pleasure of representing Densho at the 2025 Minidoka Pilgrimage. This was my third pilgrimage to a former US concentration camp used to incarcerate Japanese Americans during World War II, after two previous pilgrimages to Manzanar and Tule Lake. Each pilgrimage experience has taught me something new—not just about the wartime incarceration but also about my own family, as well as myself. This time, at Mindioka—where my grandfather and his family had been incarcerated—I learned more about the importance of collective remembrance, artistic creation, and storytelling in the long processes of healing and reckoning with historical injustice.

During the long weekend, I participated in various activities and programs, including educational presentations, a tour of Minidoka, storytelling sessions, as well as a movie screening. I had many moving and meaningful experiences, only some of which I recall here. I offer these reflections not as a “review” of the pilgrimage, but rather as a personal account of how these types of events—gatherings of community members to commemorate the past and critically reflect on the present—provide much-needed spaces of healing, connecting, learning, and belonging. Such spaces are, in my opinion, especially important for communities and individuals who have experienced violence, oppression, and marginalization, as well as for those seeking to create a more safe, equitable, and just society for all.

Engaging with the Legacy of the Redress Movement

On Friday, the first full day of the pilgrimage, I had the pleasure of co-leading two separate educational sessions. The first focused on Japanese American support for Black Reparations, and was developed by the Nikkei Progressives and NCRR (Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress) joint reparations committee—of which I have been a member since 2020. This workshop, co-faciliated with Akemi Matsumoto and Miya Osaki, explored how and why contemporary Japanese American activists—including leaders of the 1980s Japanese American Redress Movement—support Black Americans seeking reparations for slavery and its lasting harms.

By watching two educational films and engaging in lively group discussions, workshop participants learned about ongoing movements for Black Reparations, in part, drawing connections between present-day struggles and the Japanese American Redress Movement.

As a whole, the workshop emphasized the importance of solidarity in all social movements, especially those seeking large-scale systemic changes. NCRR members—who helped lead the 1980s Redress movement—have long recognized the crucial role of allies and partners, particularly several Black leaders, in achieving reparations for the harms of WWII incarceration. And now, many of those NCRR members are organizing alongside other activists, both within and beyond the Japanese American community, to support others fighting for justice and rights for their own communities—including African Americans seeking reparations. As stated by Kathy Masaoka, a founding member of NCRR who helped develop this workshop, “Fighting for and winning redress taught us the importance of standing up for others, not just because our experiences might be similar, but because they come from a system that is rooted in white supremacy. We support reparations for the Black community because it is owed, long overdue, and part of our own healing.”

In a time when our country is experiencing unprecedented division and polarization, participants left the workshop with a deeper understanding of collective power and care. We explored how something seemingly impossible—like winning redress and reparations for state violence—can become a reality when people and communities work together across racial, cultural, and generational divides, among other differences. By the end of our workshop, the room felt lighter, more hopeful, and energized.

Exploring Untold Stories and Survivor Accounts of Minidoka

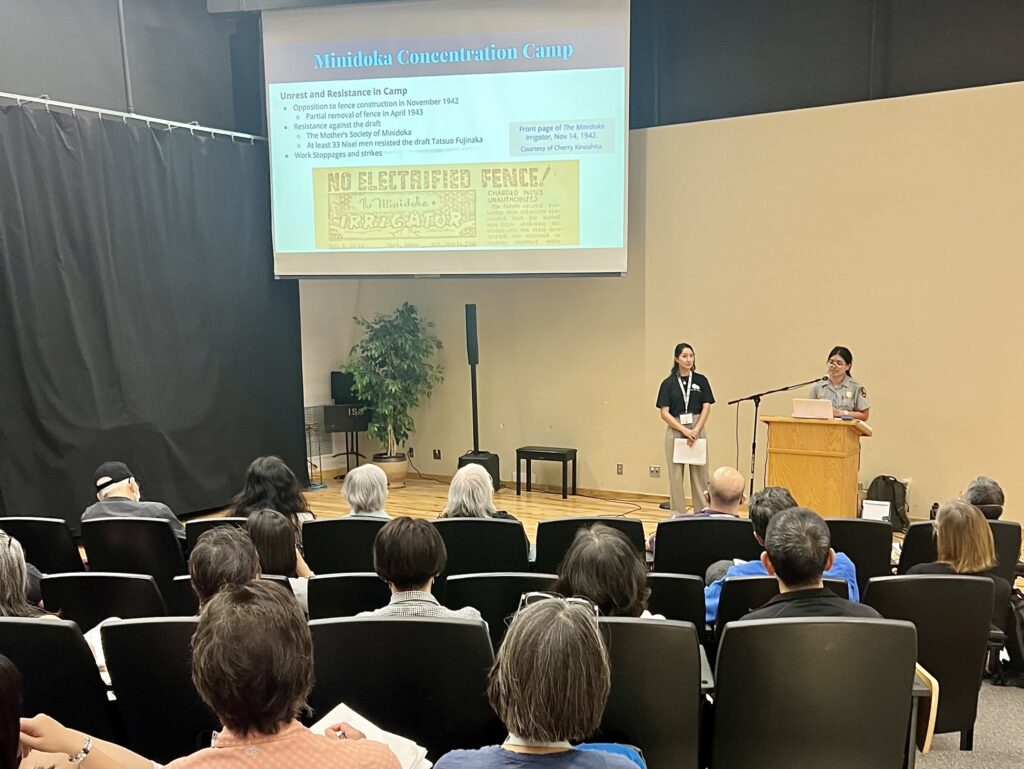

My second educational session—titled “Exploring Minidoka’s Complex History through Primary Sources”—was one that I organized on behalf of Densho, in partnership with Minidoka National Historic Site (NHS) staff members. Putting on my “Densho hat,” I co-facilitated this session with Emily Teraoka, a Manzanar NHS ranger who had previously worked at Minidoka NHS. Together, we offered participants a brief yet in-depth overview of Minidoka’s complex history, by drawing on Densho’s historical and archival resources, including important primary source materials such as The Minidoka Irrigator camp newspaper. In addition to exploring what makes Minidoka unique, we highlighted a diverse collection of stories, voices, and experiences, including those of Alaska Natives who were incarcerated in the camp.

In examining key primary sources that offer direct and firsthand documentation of the Minidoka incarceration experience, we engaged with several survivor testimonies. One was an oral history conducted by Densho with Yosh Nakagawa, who was in the third grade when he and his family were forcibly removed from their home in Seattle in 1942. We viewed one interview segment in particular, in which Yosh recalls befriending a young boy from an Alaska Native family who lived in a neighboring barrack. His oral history offers insight into the kind of discrimination that the Native Alaskan family experienced—ultimatley shedding light on this little-known part of WWII incarceration history.

After watching this oral history, we asked the audience, which was largely made up of survivors and descendants, if anyone wanted to share their own personal or familial stories. To our great honor and privilege, two Minidoka survivors and a descendant volunteered to speak, offering precious insight into the everyday lives, experiences, and hardships of Minidoka incarcerees and their families. Later, one of the three speakers confided in me that another speaker had thanked him for sharing, since his story gave this other speaker the courage to share her own story for one of the first times in public.

In a workshop focused on primary sources, we could not have been more fortunate to hear firsthand accounts from survivors and descendants themselves. As an organization dedicated to safeguarding history as told by those who lived through it, Densho strives to make these kinds of educational experiences possible, in which people can share and learn history in safe, communal, and protected spaces. Although Emily and I led the session, I am certain that I learned just as much, if not more, from my audience than they from me.

This second educational session was developed as part of a pilot training program created with and for Minidoka NHS interpretation staff—a project made possible by the generous funding of a National Park Foundation grant. Leading this session was therefore also an exciting opportunity for me to meet several of the Minidoka NHS staff members with whom I had been working throughout the past year. In addition to speaking with them in person, rather than through computer screens—which was in itself a wonderful experience—I also had the opportunity to see some of our project partners in action, leading tours of Minidoka.

Finding Ancestral Connections at Minidoka

My tour was led by Kurt Ikeda, former Chief of Interpretation and Education at Minidoka NHS, who worked with Densho to envision and develop our collaborative project. Seeing Kurt in action was nothing short of inspiring. His vast experience and skills as a tour guide were obvious through his clear articulation, provocative storytelling, as well as his thoughtful questions and remarks to the group. In addition to highlighting key historical sites, objects, and experiences at Minidoka, illuminating the history surrounding us, Kurt also encouraged us to look within. At the beginning of the tour, he asked us to ponder two questions: “What are we seeking? And who are we bringing with us on this quest?”

Upon returning to Minidoka, a site of my ancestors’ incarceration, I had thought that this trip would be dedicated to finding them—to uncovering traces of their lives, experiences, and thoughts as they were forced to live in this American concentration camp. I did not initially realize that this trip would be equally dedicated to learning about myself—my thoughts, needs, and desires for coming here. What was I seeking? Kurt’s questions raised many others, spurring a long and unfinished process of self-reflection and introspection.

As I walked over the dry barren ground, and along the concrete foundations of buildings long demolished, I thought about my grandfather. He had stayed at Minidoka for five harsh winter months, after being transferred from Tule Lake, and before receiving special permission to leave camp early to continue his education at Purdue University. I imagined speaking to him, which I had not done since his passing in 2013. In our discussion in my head, he asked me why I returned to this place—a site where he and others had never wanted to be. This question occupied my mind for the rest of the weekend and made me think critically about the paradox of healing from historical trauma in the very place where it occurred.

I came to Minidoka to connect with my grandfather and my ancestors—by standing on the land where they had once stood, and by immersing myself in the history that they had lived through. Like many others, I sought comfort and connection, and perhaps a bit of closure. Thanks to the meaningful programming and warm community offered by the pilgrimage, I found all of these things and more.

Honoring Lives Lost with the Wakasa Spirit Stone

One experience in particular allowed me to connect with my ancestors and our shared history in a deep and profound way. In yet another moment of immense privilege and honor, I accompanied a small group led by Glenn Mitsui and Nancy Ukai to the middle of a cornfield growing on Minidoka’s historic grounds. In particular, we navigated to an area near the historic site of the Minidoka camp cemetery. In this sacred place, Glenn and Nancy held a ceremony honoring all those who had been laid to rest there.

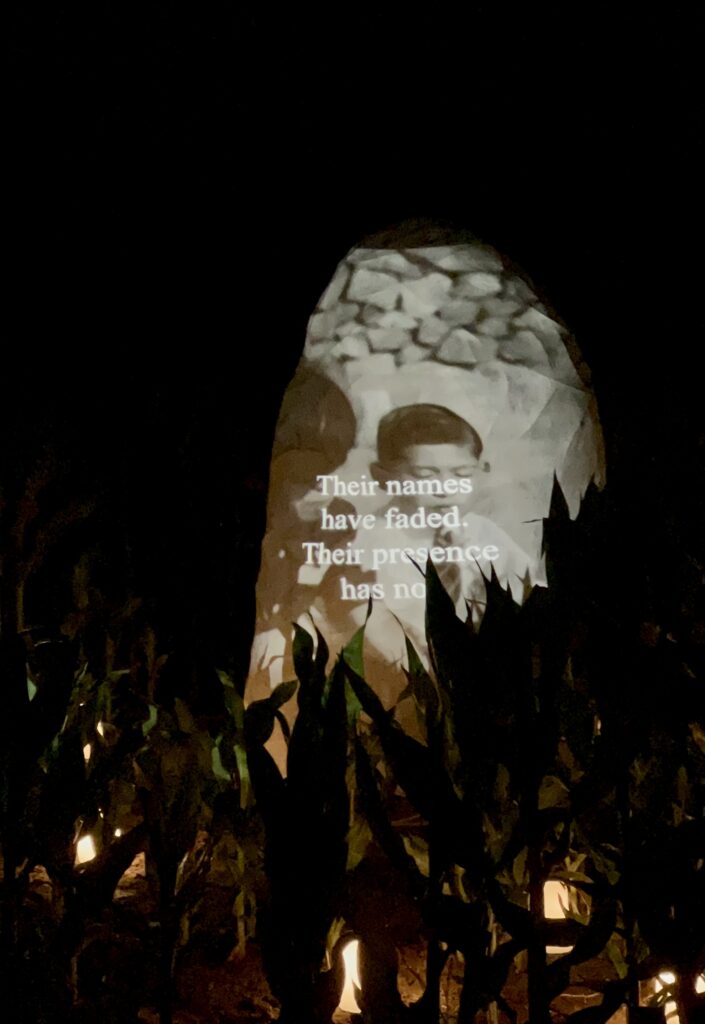

The ceremony centered around the Wakasa Spirit Stone—a traveling memorial, in the form of a washi paper sculpture, commemorating James Wakasa and the other Japanese Americans unjustly killed during the WWII incarceration. The Wakasa Memorial Committee’s mission “is to preserve their stories, inspire remembrance, and raise awareness of this history through a movable monument carried to sites of conscience… to educate, inspire reflection, and foster dialogue to ensure these injustices are never forgotten.” On this warm summer evening, Glenn and Nancy brought the Spirit Stone to Minidoka.

When Glenn first invited me to join this sacred commemoration of lives lost, he explained that it was not an “official ceremony” but rather “something we have to do.” His feelings of care, respect, and obligation were shared by the group, which was made up of descendants, close friends, and one survivor. After Glenn and Nancy shared a few words about the Spirit Stone and its meaning, the ceremony continued with the projection of beautiful and spectral images—video footage of a Heart Mountain Obon by Eiichi Edward Sakauye and photographs by Bill Manbo—on the surface of the washi memorial. These images were interspersed with the poetic words of Brandon Shimoda, and a musical chant by Mark Izu played throughout the tribute. The Stone glowed with the faces of our ancestors, some dancing the Tanko Bushi, others sitting still with their family. In that moment, in which past and present connected, we were all together as one.

After the ceremony, as we wove through the cornfields to return home, we were struck by the large full moon that had just begun to rise above the horizon. Stopping at the park entrance, we admired the open sky—a dark expanse littered with lights. The sight was particularly moving, almost haunting, as we were standing beside a reconstructed guard tower that blocked our view. The tower was a reminder that our incarcerated ancestors could not have viewed this beautiful expanse of land and sky as we did then—as people who chose to be here, who could leave freely at any moment.

The juxtaposition between the guard tower and starry night sky embodied my complex feelings about being here. Minidoka was a site of historical pain and trauma, yet also a place of community building and healing. I was grateful to the land and sky for making visible some of the internal conflicts and emotions that I felt but could not yet put into words.

Remembering “an American Story with Implications for the World”

To conclude my reflections, I want to share a brief yet special moment from the pilgrimage that made me smile. While exploring the Minidoka NHS Visitor Center, I saw one of the summer interns, Noah, whom I had gotten to know through Densho’s training program. He was in the midst of beginning his first-ever tour of Minidoka, gathering a group of visitors who were not part of the pilgrimage, and yet who had come here to learn about this critical chapter in US history.

Observing from afar, I felt happy and lucky to witness the start of Noah’s tour. When he began talking, I was immediately struck by his words. He greeted his group members and asked them to read the quote above him—a quote from Frank Kitamoto that was printed on the visitor center’s entrance. Together, they spoke these words aloud: “This is not just a Japanese American story, but an American story with implications for the world.”

—

By Jennifer Noji, PhD, Densho Development & Communications Manager.Additional Acknowledgements: We offer our heartfelt appreciation to the Minidoka Pilgrimage Planning Committee, who worked diligently to plan and execute this multi-day event. We also wish to thank Wade Vagias, Lisa Shiosaki Olsen, and their team at the Minidoka National Historic Site, as well as the Japanese American Museum of Oregon, who also helped to make this program possible.

[Header: Minidoka National Historic Site entrance. Photo by Jennifer Noji, July 11, 2025.]