December 1, 2025

Densho Content Director Brian Niiya reflects on the ways camp pilgrimages have changed over the past few decades, evolving from redress-era gatherings into expansive, intergenerational events that connect Japanese American wartime incarceration to broader histories and present-day injustices. Brian grounds these reflections in his recent experiences at this year’s Fort Lincoln and Poston pilgrimages. He shows how pilgrimages continue to thrive—adapting, expanding, and strengthening community remembrance of the past to meet the needs of the present.

Reflections on the Evolution of Community Remembrance Programs

When I returned to the continental U.S. in 2017 after over two decades of living in Hawai‘i, I started to re-engage with the Japanese American community in Southern California that I had been heavily involved in when I left. At first glance, a lot of things seemed to be largely unchanged. I had been on the staff of the Japanese American National Museum when I left in 1996, and while I had worked on various projects for them from afar, I hadn’t visited the museum on any kind of regular basis for some fifteen years.

While there was a new building and new leadership, I remember running into some of the same volunteers who had been there in the 90s. While Bill, Masako, Richard, Hal, Barbara, Nahan, and the rest were surprised I remembered them—but really, how could I not?—I was bemused that I remembered them as having been old in 1996, and yet here they were still there twenty years later, looking pretty much the same, while I looked much worse for the wear. (Some of them are still active volunteers to this day.) They were and are the soul of the museum, and as long they and others like them are still there, the museum has the same general vibe as it did way back when.

It was the same to varying degrees at other community institutions, with some of the particulars being different—and indeed with some institutions fading away (RIP Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California), while new ones formed to replace them (hello, Little Tokyo Historical Society)—but the same general feeling, whether in Little Tokyo or in suburban areas like the South Bay or San Gabriel Valley where most of our families are situated.

And then I started going to camp pilgrimages.

In my memory, camp pilgrimages—as well as the related Days of Remembrances (DoR)—were in a state of transition in the 90s. Both were in some respects vehicles of the Redress Movement, drawing from the same drive by community members to reclaim stories of the WWII incarceration, and growing with that movement through the 70s and 80s. It’s hard to remember the pre-Internet days when information traveled much more slowly, but looking back at pilgrimage and DoR flyers from that time, nearly all were focused on redress and they served as mediums to pass on information, to issue calls for action, and consolidate general community support for redress.

And then, stunningly, came the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and the culmination of the movement. While there were still issues related to redress—first, the appropriation of funds and second, clarifying who would be eligible for redress—that were addressed at post 1988 pilgrimages and DoRs, these issues applied to fewer people and, while important, didn’t inspire the same sort of urgency and energy from the entire community that redress did. With the slow passing of the Nisei generation, the pilgrimages seemed to be getting smaller and less frequent around the time I headed to Hawai‘i. I figured they might fade away as the years went on.

And I figured wrong. When I returned to the continent, there were more pilgrimages—they were more frequent, and they were bigger. The same was more or less true for Days of Remembrance programs. They had morphed into something that, while related to their original purpose, was more expansive and variable.

A key development started in the 1990s, after the Gulf War of 1990–1991 brought out latent anti-Arab/Muslim sentiment, which led some pilgrimage and DoR groups to draw on the Japanese American exclusion and incarceration experience to speak out in support of other groups similarly targeted on the basis of their race, religion, or ancestry. This general trend really took off after the 9/11 attacks of 2001. Since then, many if not most DoRs, and a fair number of pilgrimages, have taken the general tack of drawing parallels between the Japanese American WWII experience and current issues and injustices—of which, unfortunately, there have been many.

Upon moving back to Los Angeles, I joined the Manzanar Committee and have been helping on Manzanar Pilgrimages these last few years. But I also usually go to a couple of other camp pilgrimages each year, and this year was no exception.

Experiences at This Year’s Pilgrimages

The inaugural Fort Lincoln (Bismarck) pilgrimage in September—which coincided with the dedication of the Snow Country Prison Memorial—and the Poston Pilgrimage in October highlighted some key trends of the current pilgrimage scene.

Fort Lincoln Pilgrimage

I’ve written before on the remarkable Snow Country Prison Japanese American Internment Memorial at United Tribes Technical College (UTTC) before, so I won’t repeat the back story, but it was great to return to the site and see the new memorial courtyard unveiled. Designed by MASS Design Group, the memorial includes two curved walls, one with the names of the some 1,900 incarcerees who were at Fort Lincoln—courtesy of the Ireizō Project—and the other with a timeline of the site that incorporates both the Native American and Japanese American stories, flanking a Native American drum circle. Bleachers lead to a building that once imprisoned internees and is now used by UTTC to house classrooms, offices, and a library/archive. Carefully selected native plants augment the memorial.

The long but moving dedication ceremony on September 5 included speeches by UTTC President Leander McDonald, who drew parallels between the displacement of Native Americans from the region and that of Japanese Americans removed from the West Coast during World War II. The program also featured Satsuki Ina and Barbara Takei, who led the Japanese American advisory group (of which I, representing Densho, was also a member), and Masako Takahashi, whose family foundation provided much of the funding for the memorial. Revs. Duncan Ryuken Williams and Ron Kobata led a Buddhist service and also the simultaneous recitation of all of the names of Japanese Americans incarcerated at Fort Lincoln. Joseph Kunkel and Mayrah Udvardi of MASS Design discussed the meaning and process of designing the memorial. The Sloughfoot Singers opened the program and later joined a taiko performance by TaikoArts Midwest—a highlight of the program. Janet Aisawa and Osamu Uehara of Ai Dance Theater also performed a routine inspired by the incarceration.

This inaugural pilgrimage to the Fort Lincoln site highlights one of the trends of recent pilgrimages and of the camp industrial complex as a whole: a greater interest in sites other than the ten main War Relocation Authority (WRA) sites.

For instance, just a month later, a pilgrimage took place to the Crystal City, Texas, site—the third since the first one in 2021. (Though I was unable to attend, I really want to go to this one eventually, since I have a personal connection to Crystal City through my mom’s family.) During my years in Honolulu, I helped to organize the first two pilgrimages to the Honouliuli site in the 2000s. There have been virtual pilgrimages to the Fort Missoula site, as well as a pilgrimage to the site of the Sante Fe internment camp marker in 2022. These events—along with new websites and various levels of site commemoration—represent the growing interest in other parts of the internment and incarceration story beyond Manzanar and the like.

The actual pilgrimage portion of the Fort Lincoln events was relatively modest, with perhaps sixty to eighty attendees and a small number of programs about the site’s internment history. This is, in part, a reflection of it being organized at the same time as the completion of the memorial and the organizing of the dedication ceremony. But it also has to do with some of the differences between these sites and the WRA sites.

While there were many thousands of Japanese Americans held at each of the WRA sites, sites such as Fort Lincoln held a fraction of that number. Since the redress era, stories of the incarceration in WRA camps have become pretty well-known in the Japanese American community, and there are various groups tied to most of the WRA camps that have been organizing pilgrimages to them for years. In contrast, even Japanese Americans who know their family’s wartime incarceration story fairly well are often fuzzy about Issei ancestors who were swept up in the post-Pearl Harbor roundups of community leaders—perhaps knowing that grandpa, or great-grandpa, was interned at various Justice Department and army run internment camps, but not knowing much about which ones. So there was a much smaller descendant family community to appeal to.

My hope is that events and memorials like this will lead to greater understanding of the pre-EO 9066 roundup and internment, and the various detention sites that were a part of it, as well as a step towards building descendant family communities tied to each of the sites.

Poston Pilgrimage

About a month-and-a-half later, at the end of October, I was invited to speak at the Poston Pilgrimage, somewhat incongruously headquartered at the Bluewater Resort and Casino in Parker, Arizona, the town nearest to the Poston site. It was the first time I had been to either Parker or the Poston site, so I was excited to attend. It turned out to be only a four-and-a-half hour drive from my home in Los Angeles, barely longer than the drive to Manzanar and shorter than a drive to the Bay Area.

The Poston Pilgrimage was more of a “typical” pilgrimage, in that it was organized by an organization—the Poston Community Alliance—that had been organizing them for a number of years (since 2018). It was attended by around 300 people, most seemingly with familial ties to the site, and it included educational workshops on incarceration history and current work at the site. Though I didn’t know many of the attendees going in, it nonetheless felt familiar with a vibe similar to other pilgrimages to WRA sites.

Poston and Fort Lincoln highlight a second trend of recent pilgrimages: the intentional highlighting of connections between the Japanese American incarceration experience and the experiences of other communities, in particular Native American communities. While this is something you see at many pilgrimages, the unique histories of the Fort Lincoln and Poston sites make these stories particularly salient.

As many reading this will know, Poston was the only WRA camp that was jointly run with what was then called the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA), an arrangement that did not go smoothly given the dramatically different goals of the two organizations. Poston was also built on land controlled by the OIA and was a part of the Colorado River Indian Reservation; the OIA proceeded with the building of the Poston camp over the objections of the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) Tribal Council. The site remains on reservation land, so the Poston Community Alliance has to work closely with CRIT in planning pilgrimages, as well as doing preservation, memorialization, and archeological work on the site. The weekend events served as a constant reminder of the connections between Japanese Americans incarcerees and descendants and the tribal members.

Having the largest initial population of any of the WRA camps (post-segregation Tule Lake eventually had a larger population), Poston consisted of three separate camps—generally referred to as Units I, II, and III—that were located about three miles apart from each other and that were somewhat separately administered. Unit I, the largest with a capacity of about 10,000, was laid out more or less like similarly sized camps, such as Manzanar or Heart Mountain, while Units II and III were each about half the size.

Poston Community Alliance President Marlene Shigekawa greeted us on Friday night and introduced a panel discussion that featured five speakers. Three of them, Jane Katsuyama, Tom Nishikawa, and Bob Shintaku, were Sansei who were incarcerated at Poston as children, and they talked about their memories of Poston as well as their families’ post-camp experiences. Shintaku in particular had an unusual story, since he family moved to Texas, and he largely grew up there. Needless to say, Texas was not a popular resettlement destination for Japanese Americans! I hope we can do an oral history with Bob at some point. But beyond the specifics of their experiences, these were stories similar to those one might hear at any camp pilgrimage.

The other two speakers were anything but that. Debbie Pettigrew and Karen Harjo were descendants of the Hopi families who moved into Poston in September 1945, as Japanese Americans were moving out. The two populations lived side-by-side for a short period of time. Both Pettigrew and Harjo shared family lore about that time and talked about the impact of the Poston site after the war. Amelia Flores, chairwoman of CRIT Tribal Council, also spoke and welcomed us.

On Saturday, we traveled by bus to the CRIT Museum for the opening ceremony, which featured dancing and singing by the Ase S’maav Parker Boys and the River Tribes United Dance Group. Rev. Duncan Ryuken Williams led a Buddhist prayer and the reading of the names of those who died at Poston, before inviting the performers and tribal leaders to stamp the Ireichō. We had just a few minutes to visit the museum, which features a section on Poston and the Japanese American incarceration.

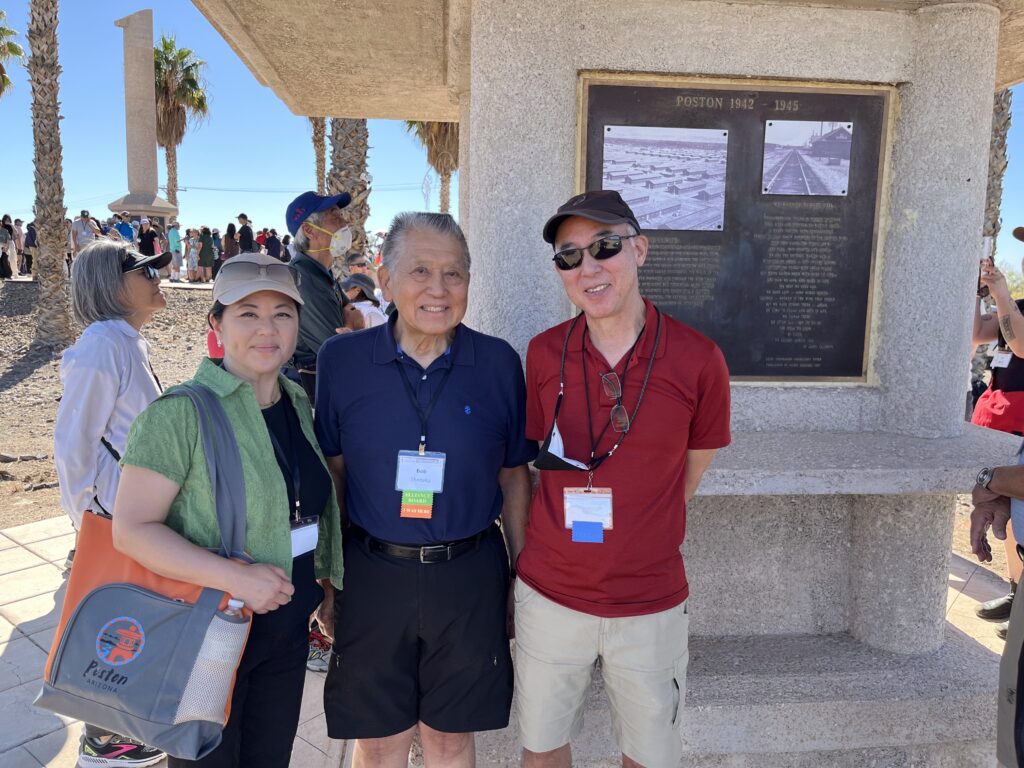

From there, we headed down the road about eighteen miles to the Poston Memorial Monument, which was built in 1992, with an information kiosk that went up in 1995. The memorial is located on Mohave Road and is accessible to the public.

Next, we visited the site of the Unit I school complex. Located more or less in the center of Unit I, the school included adobe classrooms that were built largely by women incarcerees along with a school auditorium and library. Many of the buildings, which were used by CRIT and the Parker School District until 1980, are still standing. Though badly damaged by fire, the ruins of the auditorium also remain. There is ongoing preservation work at the site, including the preservation of a Poston barrack. Walking the expansive school site in what was fairly intense heat, even in late October, provided just a glimpse of what life must have been like for those incarcerated here eighty years ago.

From there, we headed to Le Pera School for lunch and the afternoon workshops. The original La Pera School used the buildings from the Poston Unit II school for years, though the current school buildings have been newly built. I believe the school remains on the Unit II site, or least close to it. The workshop included a mix of topics related to Poston, from scholarly research to site preservation to broader topics on the incarceration, and was reminiscent of similar workshops offered at several other pilgrimages. It was great to renew acquaintances with friend-of-Densho Hana Maruyama, now an assistant professor of history at the University of Connecticut, who talked about her Fudeko Project—a directed writing project named after her grandmother. It was also great to meet two advanced doctoral students, Katie Nuss Louis (who is also the vice president of the Poston Community Alliance) and Christina Hiromi Hobbs, who are both completing Poston-related dissertations in anthropology and art history, respectively. I look forward to learning more about their work.

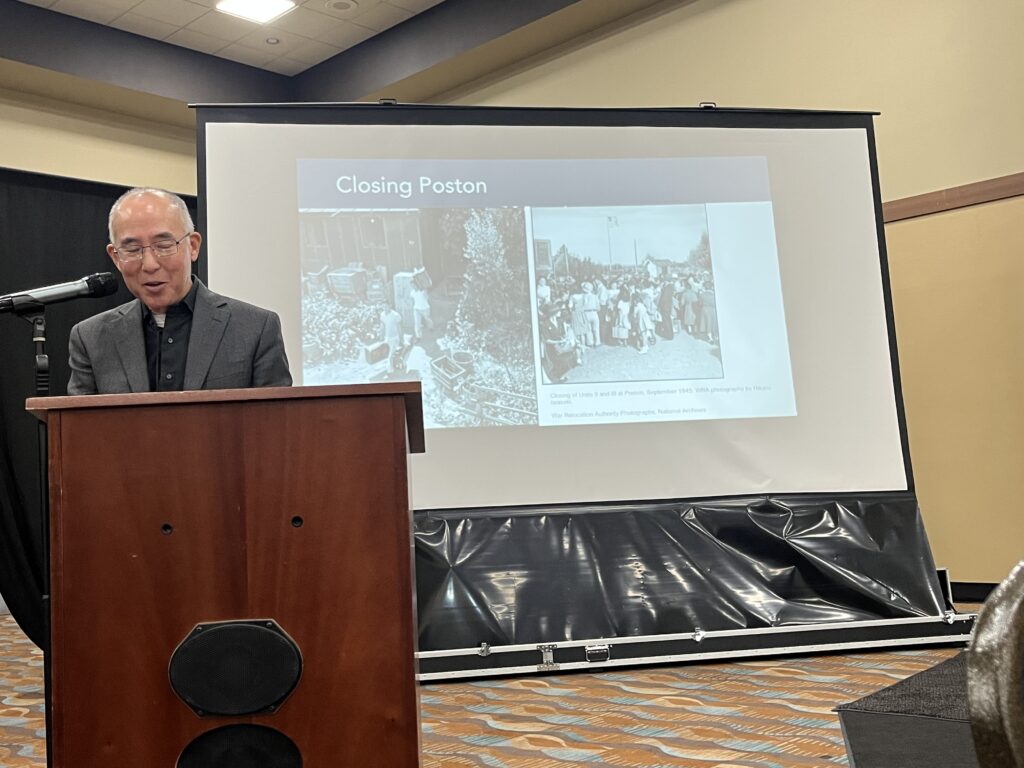

The pilgrimage ended with a dinner at which I was honored to give the keynote address, which focused on the closing of Poston eighty years ago and patterns of the resettlement and return of Poston incarcerees. I suspect I may have raised more questions than I answered. The evening ended in an unexpected and moving way: a cello performance by Jane Katsuyama, a former Poston incarceree who was a professional musician after the war in Dayton, Ohio. It was a fitting end to another pilgrimage.

I returned home energized by these pilgrimages—by the warm and intergenerational attendees, the impressive work being done at the sites, and by the inspiring welcomes by tribal communities. So indeed, camp pilgrimages not only are surviving, but are thriving and evolving as well. I’ve learned my lesson and will refrain from predicting their demise anytime soon.

—

By Densho Content Director Brian Niiya. Thank you to Marlene Shigekawa, the Poston Community Alliance, and United Tribes Technical College.

[Header Photo: Photo of Snow Country Prison Memorial wall. Courtesy of Brian Niiya.