November 11, 2024

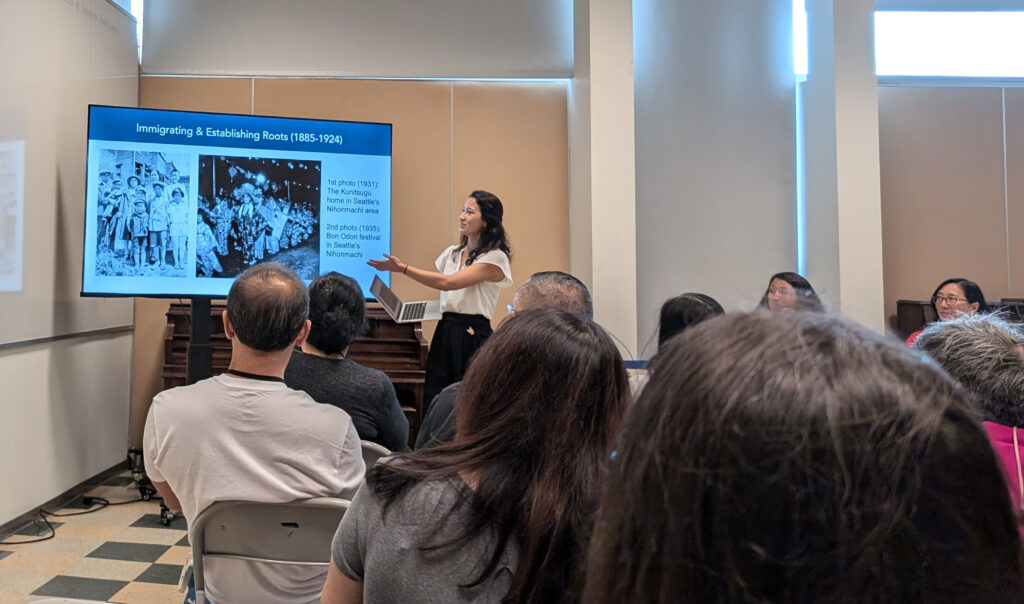

Last month, Densho was invited to participate in Tsuru for Solidarity’s multi-day event Kintsugi 2024—a first-of-its-kind gathering for Japanese Americans focused on intergenerational trauma and repair. Densho Staff Writer and Project Coordinator Jennifer Noji joined teachers of the Rosa Parks Japanese Bilingual Bicultural Program in a workshop on “Reclaiming our Language, Culture, and History.” She shares some of that Kintsugi presentation here, offering an overview of Densho’s efforts to revive and preserve our language and culture, as well as a brief history of how and why they were lost in the first place.

A Brief History of Forced Assimilation and Language Loss

Prewar Prejudice (1885-1941)

From 1885 to 1924, approximately 200,000 Japanese people immigrated to Hawai’i and 180,000 immigrated to the mainland US. Through arduous work, often in agriculture, many of these Issei built vibrant communities in their new homelands, raising families, starting churches, and forming social and business organizations. They also created Japantowns (or Nihonmachi) in their new towns and cities, many of which included Japanese language schools (discussed in more detail below). In addition to smaller enclaves, there were over 43 established and recognized Japantowns before the war. In these communities, Issei and their Nisei children kept Japanese culture alive, including traditional Japanese customs like Bon Odori and other celebrations.

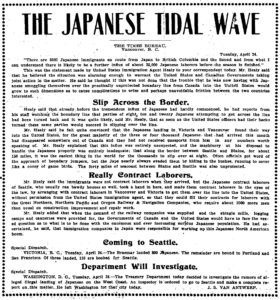

However, in response to the success of Japanese immigrants, a wave of nationalistic, anti-Japanese sentiment began to grow stronger among white mainstream Americans. Inflammatory news articles and propaganda began to circulate about the “threat” of Japanese immigrants and their children.

Demonizing news articles and publications inflamed anti-Japanese racism and led to the creation of widespread stereotypes of Japanese people as “treacherous” and “unassimilable” aliens—people sent from Japan as part of a “Colonization Scheme.”

As Japanese immigrants were seen as more and more of a “threat” (especially by white landowners and laborers), Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924 (also known as the Johnson-Reed Act), which effectively banned Japanese migration to Hawai’i and the United States and prohibited Japanese travel to America. Alongside this immigration exclusion law, Issei also had to deal with exclusionary citizenship and land ownership laws.

These legal policies not only responded to but also further fueled anti-Japanese attitudes throughout American mainstream society. As racism and discrimination toward Issei and Nisei increased, which included physical forms of violence, more and more Japanese families felt the pressure to assimilate and become American. Nisei in particular, who were born as American citizens to Japanese parents, felt the pressure to assimilate, and many immersed themselves in American culture, joining typical American clubs and sports teams, and speaking primarily English. Thus, due to both social and legal pressures, Nikkei slowly began to lose their culture, including their ancestral language.

The history of Japanese language schools serves as a prime case study for demonstrating the transformation of the Japanese American community, in particular, showing how growing anti-Japanese sentiment and policies led to the destruction of Japanese culture and language.

As Issei established Japanese communities in Hawai’i and the mainland US, many Nisei children began to attend Japanese language schools that were often associated with Buddhist or Christian churches. To develop a more stable labor population and to ensure Japanese children could easily transition to schools upon their return to Japan (since Issei still assumed they would eventually return to Japan), both sugar planters in Hawai’i and their Issei parents encouraged the growth of Japanese language schools, which also provided needed childcare services for Japanese day laborers. By 1920, there were over 163 Japanese language schools in Hawai’i alone, educating nearly 20,000 students.

However, Japanese language schools soon became sites of controversy as some whites perceived them as institutions that taught not just language but also nationalistic Japanese sentiment. Despite their innocuous beginnings, Japanese language schools soon became embroiled in controversy as they became associated with labor movements, issues of loyalty and national allegiance, and growing local and national anti-Japanese sentiment.

As a result, bills were passed in both Hawai’i and the mainland US to restrict the operation of language schools, including discriminatory tax policies, unreasonable teacher qualifications (the Parker Bill), and limited operation hours. Consequently, in line with a growing anti-Japanese movement in the continental United States and Hawai’i, Japanese language schools began to shut down due to increased operational costs and excessive restrictions. Around this time, Congress also passed the 1924 Exclusion Act (mentioned above). Collectively, these events signaled a new era of tighter oppression by political and economic leaders in Hawai’i and the US. Eventually, Japanese language school teachers and principals would be among the first to be apprehended and incarcerated during World War II, and the war would officially lead to the closure of all remaining schools.

WWII Mass Removal & Incarceration (1942-1946)

The outbreak of World War II brought a whole new set of problems for Japanese Americans, namely, their forced removal and incarceration. After the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the US president signed the infamous Executive Order 9066, authorizing the mass removal and incarceration of people of Japanese descent from the West Coast into temporary detention facilities, military internment camps, and concentration camps run by the War Relocation Authority (WRA)—the federal agency created in 1942 to oversee the displacement and imprisonment of these Japanese Americans.

Needless to say, the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans further exacerbated the population’s loss of their Japanese language and culture. In addition to dissolving the language schools and prompting many families to destroy cultural artifacts that might make them look “disloyal” in the eyes of the state, the forced removal led to the decay and destruction of flourishing Japanese communities, including many established Japantowns. These prewar communities would never be rebuilt to the same extent after the war.

The loss of culture and language continued throughout the incarceration period, especially among the younger generations. A key site of forced assimilation and cultural erasure included the camps’ WRA-run schools. These schools were quickly organized throughout the ten primary concentration camps, but they suffered from crude facilities and lack of teaching materials. Instruction was given for nursery through high school, and even some adult education was offered. However, trained teachers were in short supply, and uncertified Japanese Americans with college degrees often filled in.

In stark contrast to the prewar Japanese language schools, these schools not only taught strict American educational curricula but also enforced American customs and practices, such as mandatory recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance. In accordance with this American education program, students were prohibited from speaking Japanese or learning about Japanese history and culture. These WRA-run schools thus significantly contributed to the state’s overarching “Americanization” efforts to turn Japanese Americans into loyal American citizens who could eventually be reintegrated into society after the war.

While Japanese American school children grew disconnected from Japanese culture and language through education in camp, several thousand Nisei men also developed a strained relationship to their cultural heritage during the war. These Nisei men—many of whom were Kibei born in the US but educated in Japan—served as Japanese linguists within the state’s Military Intelligence Service.

Fighting in the Pacific theater of the war necessitated Japanese linguists for translation, interpretation, and combat purposes. When American military officials discovered the lack of skilled Japanese linguists among white personnel, they recruited Nisei soldiers to attend the Military Intelligence Service Language School. This school was critical in producing skilled linguists who were essential in the Pacific War and later the occupation of Japan.

Unlike the previous examples discussed above, the case of Nisei linguists shows an ironic and tragic reversal in which Japanese Americans are, for the first time, encouraged to learn and speak Japanese, however, not for the sake of maintaining and enriching their culture. In fact, it’s quite the opposite: these Nisei men were encouraged to learn Japanese in order to support the American war effort and fight Japan in the Pacific. In other words, Japanese became a tool for defeating their ancestral homeland rather than connecting with it. By recruiting and training Nisei linguists, the US government further complicated Japanese Americans’ relationship with their language and culture.

Postwar and Resettlement (1945 onward)

The Japanese American population’s loss of culture and language continued even after the war ended. While the removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans offered the state an immediate solution to the “Japanese problem” at the beginning of the war, the incarceration also gave the government a unique opportunity to refashion the incarcerees into model American citizens or a “model minority,” via state-engineered assimilation programs. The WRA and state officials therefore began to develop and push what they called “resettlement”—an initiative for moving “loyal” Issei and Nisei from camps into mainstream American societies.

The WRA implemented this “resettlement” program as early as Spring 1942, by allowing Nisei college students to resume their studies at particular universities and by letting some incarcerees temporarily leave camp to work in agriculture. After these initial “first leave” programs were declared a success, the WRA began to expand its efforts, hoping to push out as many “loyal” incarcerees as possible from camp into mainstream society. This process involved distributing the infamous “loyalty questionnaire,” which was supposed to more easily separate “loyal” incarcerees from “disloyal” ones. (Instead, their over-simplistic and controversial questions caused large-scale unrest and tension among the incarcerees.)

While the state had various motivations for resettlement, one major motive was to ease labor shortages. Another was to weaken the Japanese American population’s cultural and economic power, by scattering Nikkei around the country. Plus, WRA leadership believed that dispersing Japanese Americans and integrating them into white mainstream society would prevent them from becoming dependent on the government, for example, for social and economic welfare.

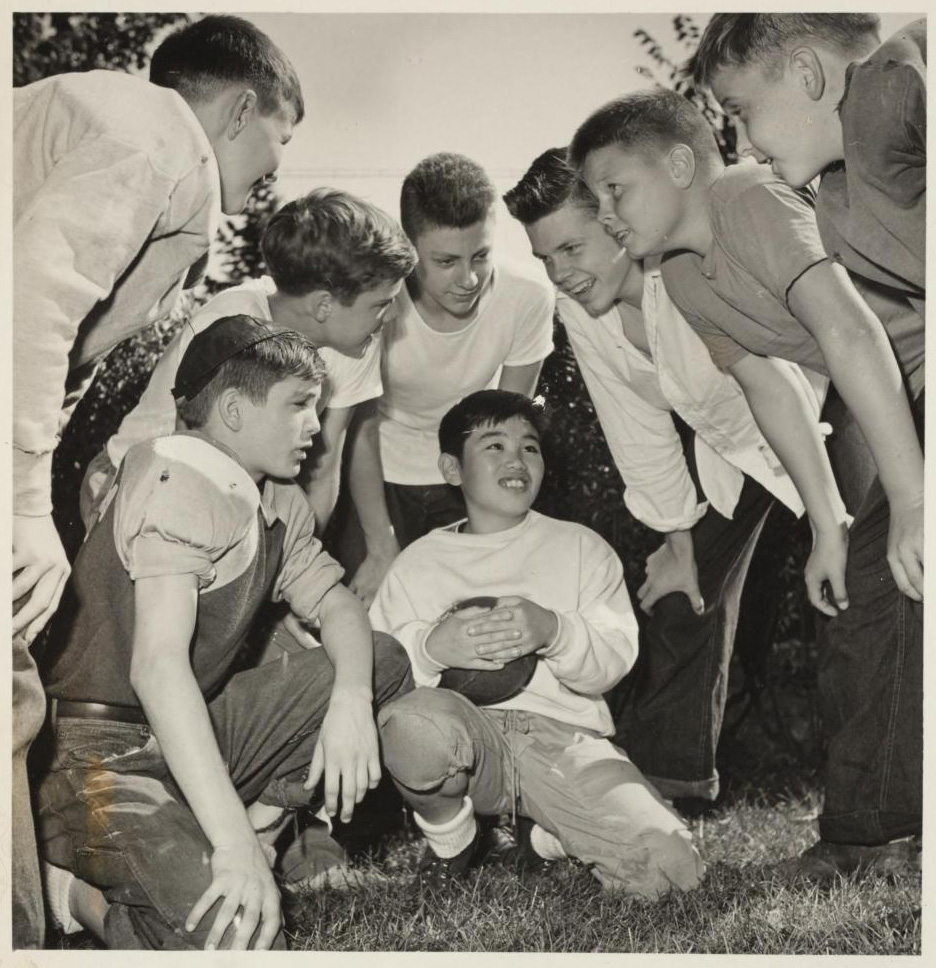

In order to garner support for their vision of “Resettlement,” the WRA distributed highly staged photos among the camp incarcerees, depicting Japanese Americans living as happy American citizens outside of camp. The photos suggested that integration into the outside world was actually quite appealing and promising. Although many incarcerees remained skeptical, they would eventually be given no choice but to leave camp in 1945 (and 1946 for Tule Lake incarcerees). Given $25 and a one-way transportation ticket, each incarceree was forced to move and start life anew once again.

After leaving camp, Japanese Americans would continue to face immense pressure to assimilate into white mainstream society. Much of this pressure came from WRA leaders and officials, who repeatedly emphasized that Issei and Nisei should “avoid segregation at all costs” and should avoid speaking Japanese and engaging in Japanese cultural activities. They were also encouraged to join hakujin (white) groups, churches, clubs, and professional associations whenever possible.

The pressure for Japanese Americans to become fully American and to leave behind Japanese language and culture thus started before the war and continued long after.

Contemporary Efforts to Reclaim Our Language and Culture

Despite this long history of racial discrimination, cultural oppression, and forced assimilation, the past few decades have witnessed a rise of Japanese Americans seeking to reclaim their culture, language, and history. Especially following the 1980s Redress Movement—led by Sansei seeking reparations for their families’ immense loss and trauma caused by the war—a growing number of Japanese Americans (including myself) are striving to reconnect with their cultural heritage and ancestral language.

Densho shares that dedication to reclaiming and sharing our cultural heritage. Indeed, a cornerstone of Densho’s work is our Oral History Program, which has amassed over 1,000 interviews with camp survivors and their direct descendants. By empowering survivors and descendants to tell their stories, Densho seeks to not only document history but to facilitate community healing and repair.

Densho also seeks to aid our community members in rediscovering their history and culture through a variety of family history and genealogy services, including our Densho Digital Repository, Names Registry, Densho Encyclopedia, and Sites of Shame. In addition, Densho’s Koseki Retrieval and Translation Service provides assistance to families in navigating privacy laws and language barriers to request their koseki (family registers), the most important genealogical documents for tracing your ancestry in Japan.

Alongside critical organizations like Tsuru For Solidarity and the Japanese Bilingual Bicultural Program, Densho will continue to support and empower Japanese American community members to reclaim their ancestral language, culture, and history, and we will fight to ensure that they are preserved for generations to come.

—

By Jennifer Noji, Densho Staff Writer and Project Coordinator

Information sourced from Densho Encyclopedia, Densho Digital Repository, and Densho Catalyst, in addition to the California Japantowns website. Sections of the article are adapted from Kelli Y. Nakamura’s Densho Encyclopedia entry “Japanese Language Schools” and Ellen D. Wu’s Densho Encyclopedia entry “Resettlement in Chicago.”

We encourage you to learn more about the Japanese Bilingual Bicultural Program at Rosa Parks Elementary School, which is a unique foreign language program that integrates instruction by native Japanese speaking Sensei with a rigorous core curriculum taught in English—all in an environment that promotes community, diversity, and positive values. JBBP was founded in 1973 to preserve and share Japanese language and culture for future generations and to reclaim cultural identity lost in the aftermath of World War II incarceration. Please email info@jbbpsf.org to learn more about the program.

[Header: Jennifer Noji (middle) stands with teachers of the Japanese Bilingual Bicultural Program, Lisa Tsukamoto (left) and Cecily Ina (right). Jennifer, Lisa, and Cecily served as the speakers of their Kintsugi workshop, while Grace Morizawa (not pictured) moderated. Photo taken October 5, 2024.