March 27, 2023

A proposal to build a 76,000-acre wind farm surrounding the former Minidoka concentration camp threatens to erase the site’s historic legacy. The Bureau of Land Management is accepting public comments on the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for this proposed project until April 20, 2023. Here’s what you need to know about the history behind Lava Ridge and how you can make your voice heard.

Today, the American West is witnessing a new land rush. As climate change pushes the US away from fossil fuels, a boom of clean energy projects have appeared across the American interior. Whether it be solar or wind energy, huge swaths of lands are being claimed by energy companies to promote the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy. With renewed support from the Biden Administration and the Inflation Reduction Act, there is hope that the drive for clean energy will contribute to reducing US carbon emissions.

As part of this land grab, though, are several questions regarding the selection of sites for wind and solar farms. As The Los Angeles Times reported in August 2022, clean energy projects, like other large infrastructure projects, can potentially uproot communities, disturb natural habitats, and damage historic sites if conducted without oversight.

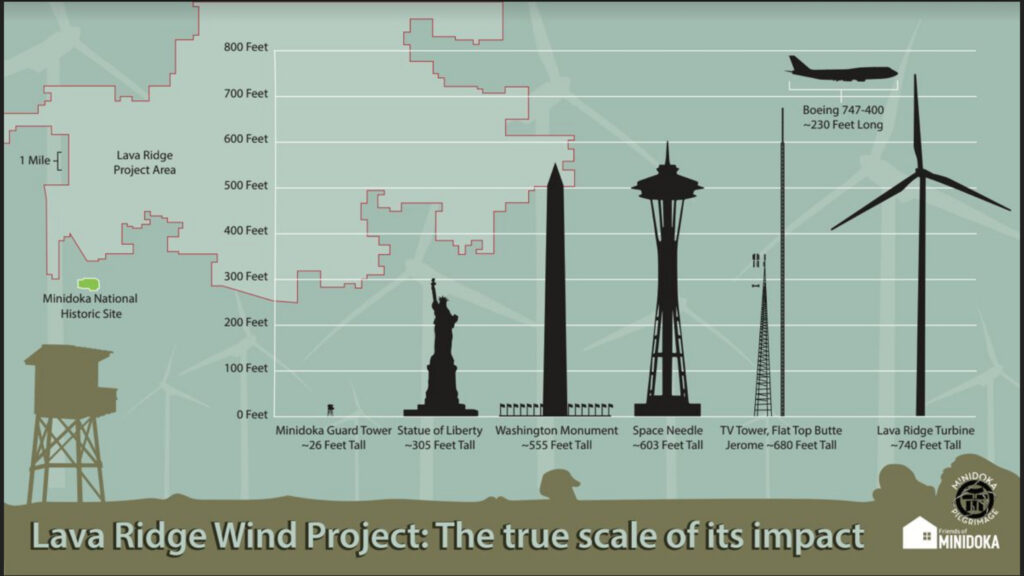

This is the case with the proposed Lava Ridge Wind Farm project. In August 2021, Magic Valley Energy proposed a 76,000-acre wind farm that surrounds the Minidoka National Historic Site. Up to 400 wind turbines, each of them up to 740 feet tall, would be sited adjacent to the former WWII incarceration site. “These windmills are not small,” Minidoka survivor Lawrence Matsuda told KUOW. “The Space Needle is 650 feet tall. So you’re talking about putting 400 Space needles around a historic site.” Part of the proposed site would fall within the historic footprint of Minidoka, and the transmission line that would distribute the power from the windmills would lie on the site of the railroad tracks that brought prisoners to the camp eighty years ago.

Upon learning of these plans, members of the Japanese American community quickly mobilized in opposition. Survivors and descendants have spent much of the past year urging the BLM not to approve the wind farm at its current site.

“Minidoka is a sacred place where our spirits come back and speak to us,” Dan Sakura, whose father was imprisoned at the camp as a child, told Grist last year. “We would like to preserve that and make sure that our children, our children’s children, and our great-grandchildren will be able to speak with the spirits that are left behind in Minidoka.”

Mary Tanaka Abo was incarcerated at the camp at just two years old. “To me, Minidoka is a place of memory, history, a place of reflection and of healing,” she said at a recent BLM open house in Seattle. “You don’t compromise a sacred place. It has to be as it is, as it was.”

Sadly, the Minidoka Wind Farm crisis is not the first time a clean energy project threatened the integrity of a former camp site. In 2013, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power announced the construction of a large-scale solar farm — 1,200 acres in total, roughly the size of West Hollywood — directly adjacent to the Manzanar National Historic Site.

Immediately, the proposal elicited outrage from former Manzanar survivors and the Los Angeles Japanese American community. The Manzanar Committee, led by chairperson Bruce Embrey, voiced their frustration towards LADWP’s “gross insensitivity” of intentionally selecting the lands surrounding the Manzanar Historic Site as the proposed location for the solar farm.

After months of heated public meetings and a letter-writing campaign by survivors, historians, and the Manzanar Committee, the LADWP announced a pause on constructing the solar farm. As of 2015, the project remains on hold.

These proposals are part of a larger history of disruptive infrastructure projects encroaching on spaces held sacred by marginalized communities.

In the early 1950s, the city of Tulelake destroyed over two-thirds of the former Tule Lake Segregation Center — including the camp cemetery — to build an airfield for local crop-dusters. More recently, in 2013, Modoc County announced plans to construct a three-mile-long, eight-foot-high barbed wire fence around the perimeter of that airfield, sparking outrage from Tule Lake survivors, descendants, and the broader Japanese American community. Those plans have been stalled thanks to a decade-long fight spearheaded by the Tule Lake Committee, but the threat still looms.

Meanwhile, many historically Black, Latinx, and Asian neighborhoods in cities across the country — including once-bustling Japantowns up and down the West Coast — have been decimated by decades of urban renewal, freeway construction, and gentrification.

This pattern of claiming land in the name of “public good” stretches back to the founding of this country on stolen Indigenous land — and continues today at Mauna Kea, the Weelaunee Forest outside Atlanta, Chinatowns in Los Angeles and Seattle, and yes, historic sites like Minidoka, Manzanar, and Tule Lake.

In both the case of the Manzanar Solar Farm and the Minidoka Wind Farm, the emotions of former incarcerees can be summed up in one question: haven’t we endured enough? Although these projects come with good intentions, they undermine the integrity of the environmental justice movement. The selection of a site in direct proximity to Minidoka — one of the few federally recognized sites of Asian American history in the United States — instills a sense of distrust in camp survivors towards these much-needed clean energy projects.

But there is also the chance to transform this dilemma into a learning lesson. If the BLM listens to groups like the Minidoka Pilgrimage Planning Committee and Friends of Minidoka, it can serve as a model for future clean energy projects that center those communities most impacted and deliver true climate justice.

Learn more about how to submit public comments on the Lava Ridge proposal here. Make sure to send in your comments by April 20th!

—

By Jonathan van Harmelen and Densho Media & Outreach Manager Nina Wallace

[Header: Two children playing in Minidoka. Courtesy of Friends of Minidoka.]