July 7, 2017

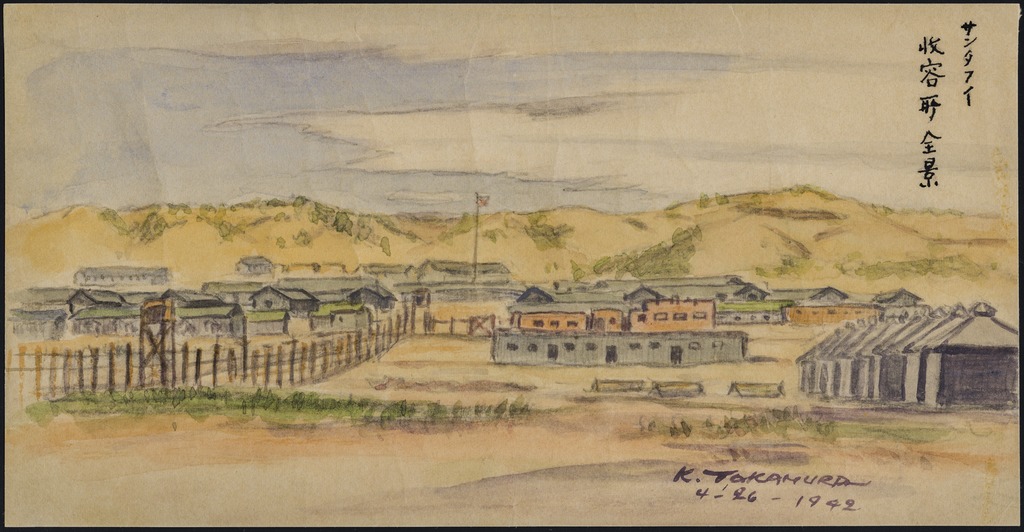

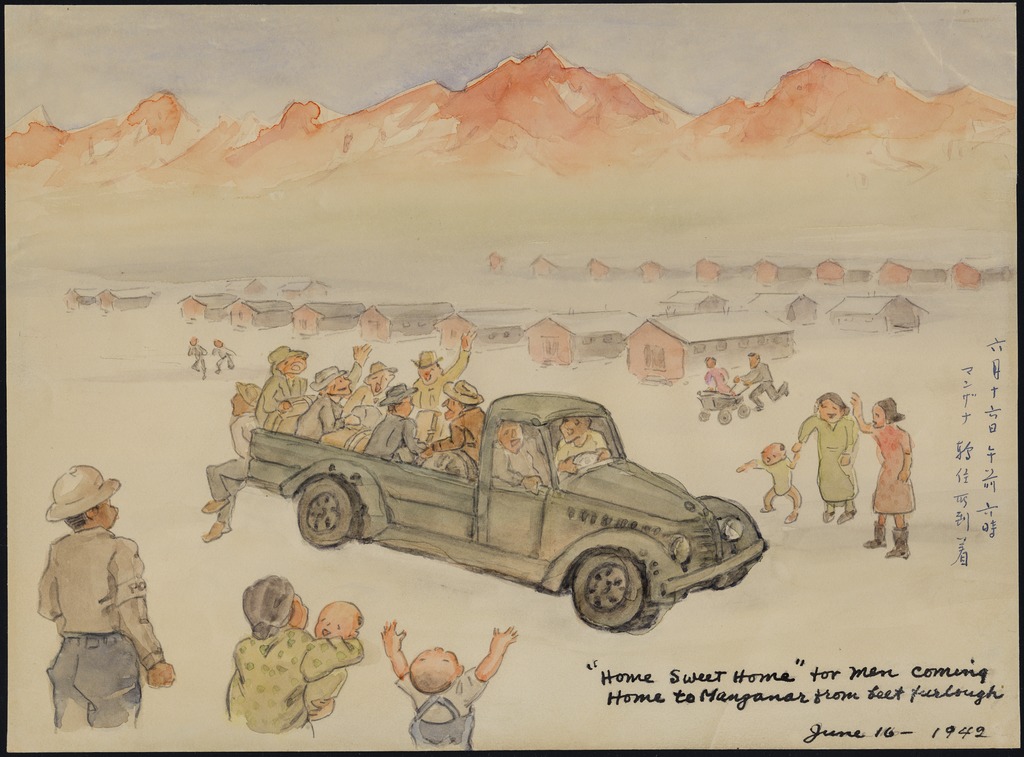

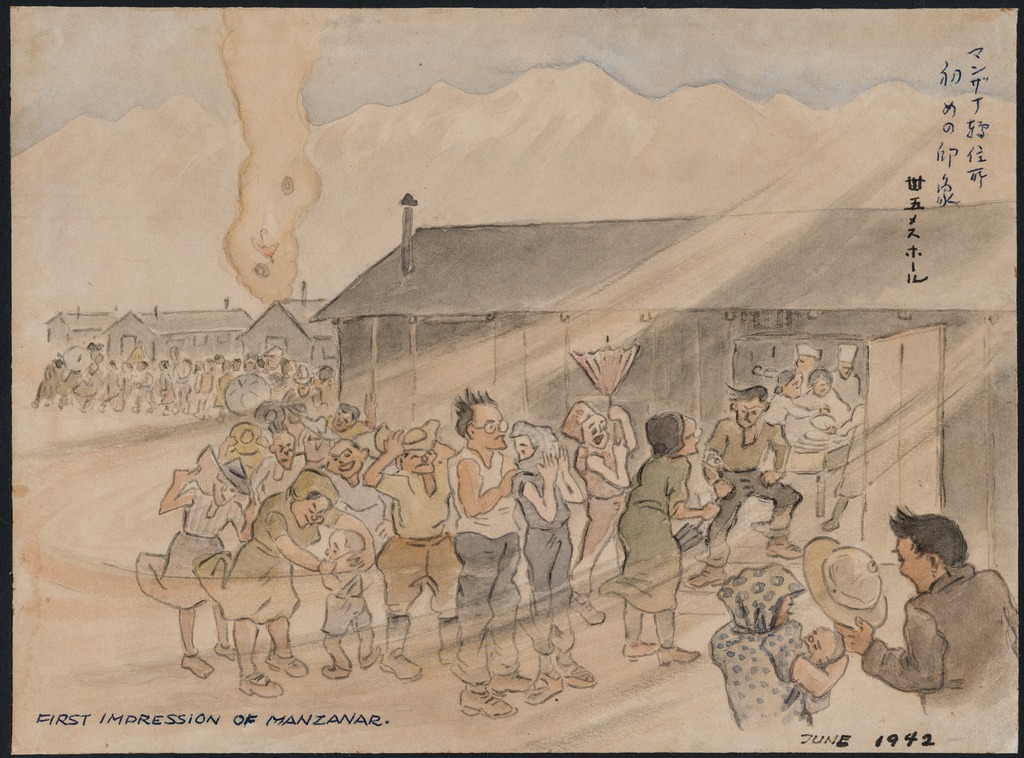

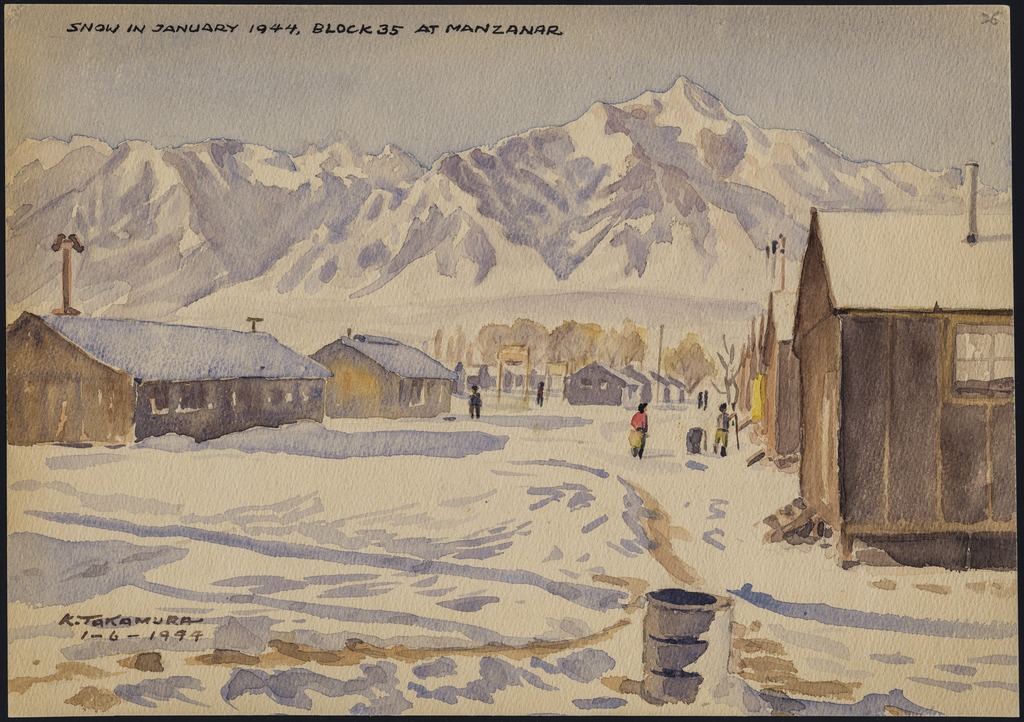

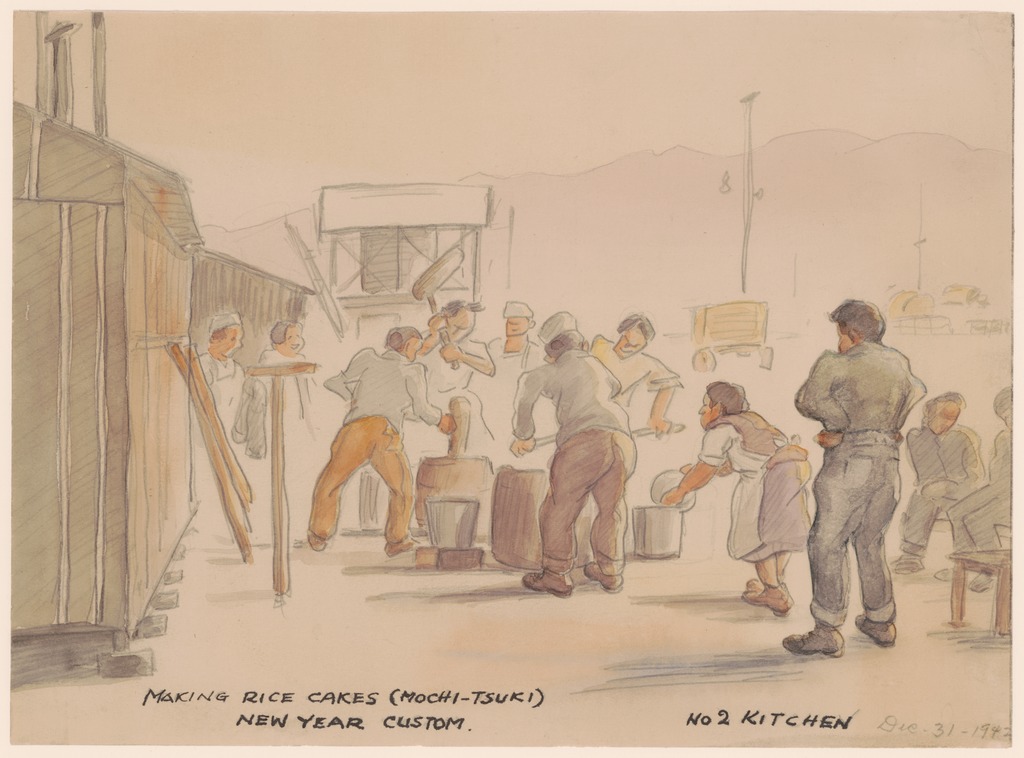

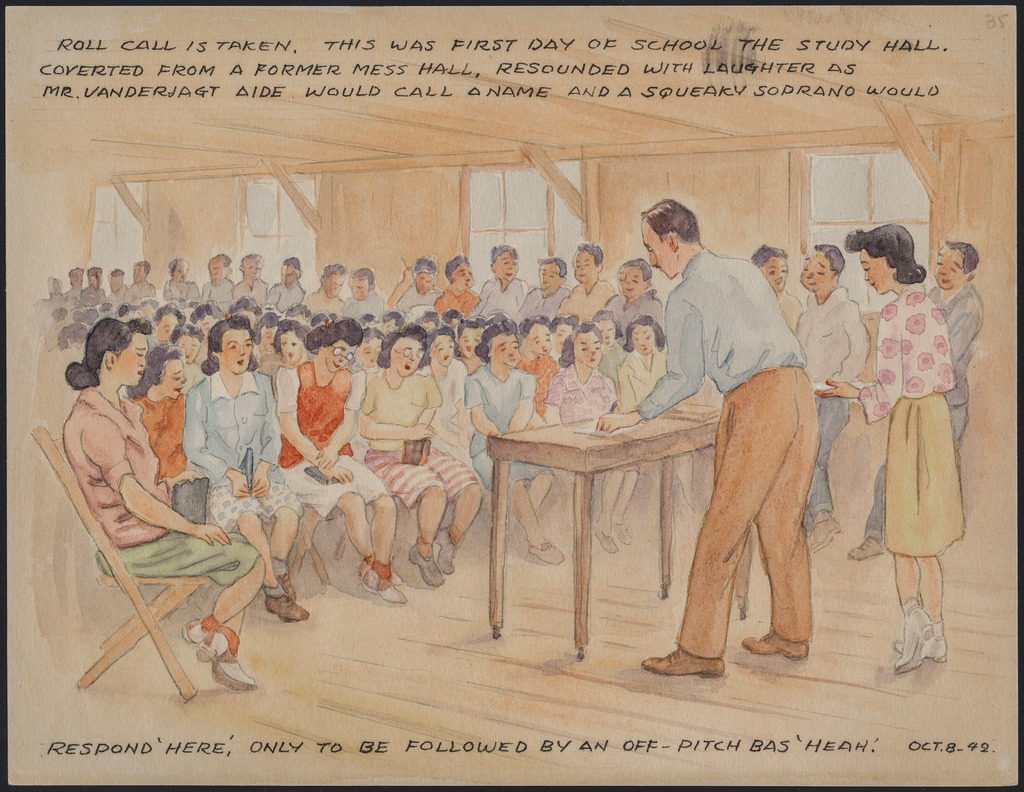

“You are not allowed to shoot photographs. That’s why I sketch exactly what was, everything I saw. It was exactly like this,” Takamura later recalled. [1]

Born in Kumamoto-ken, Japan in 1895, artist Kango Takamura immigrated to the United States when he was seventeen years old. He lived in Hawai’i for ten years, then his interest in the motion picture industry brought him to New York. There, he worked at the Paramount Studios before relocating to Hollywood. He took a job in Los Angeles with RKO studios, where he worked on film projects like King Kong (1933) and retouched publicity photographs. He aspired to be an assistant cameraman but was told he was “too short, too small.”[2]

After he arranged to sell a motion-picture camera to a visiting Japanese general, Takamura aroused the suspicion of the FBI. He later explained that he was simply looking to make a little extra money. [3] Nevertheless, he was placed under observation and then arrested shortly after the Pearl Harbor bombing. He was held at the Santa Fe detention facility for several months, then relocated to the Manzanar concentration camp. His images and handwritten captions, paired with recollections from an interview he conducted at age 88, reveal intimate details of daily life in both facilities.

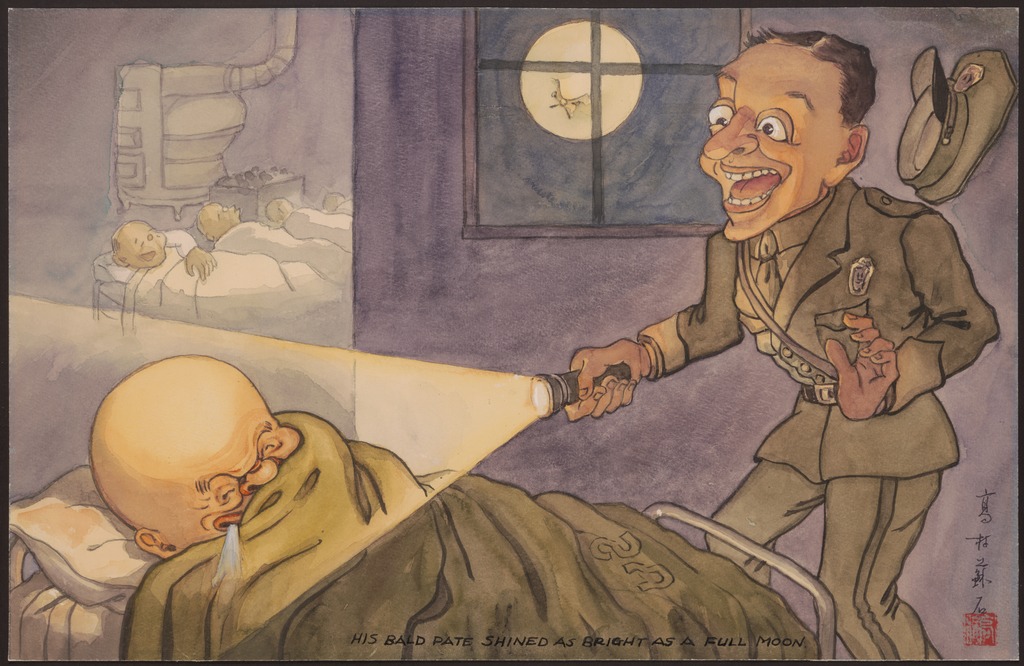

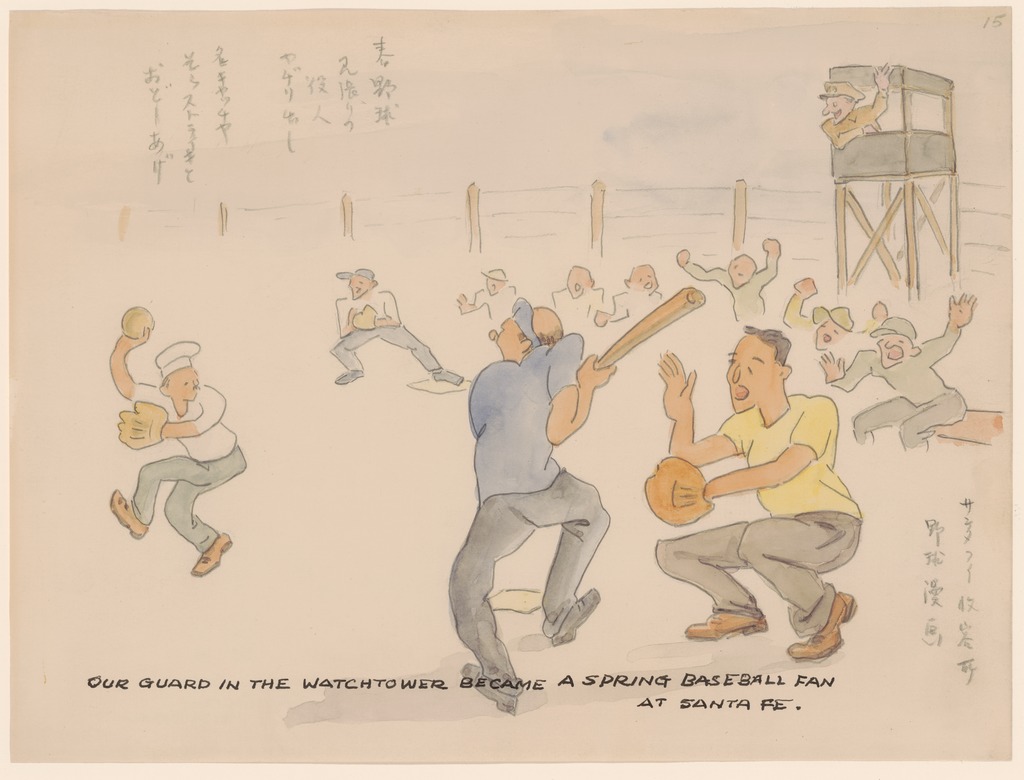

Since Takamura was initially uncertain about whether or not his sketches were permissible, he often gave them a cartoonish effect in order to make them seem more benign.

“As you know, we cannot use any camera. So I thought sketching’s alright. But I was afraid I was not supposed to sketch. Maybe government doesn’t like that I sketch…so I work in a very funny way purposely, made these funny pictures.” [4]

“Very often we play baseball. This is the kitchen band. And always the umpire says ‘fifty-fifty’—nobody wins or loses. Always fifty-fifty. And after that, they made noodles for people, you see. So people appreciate so much. This is the way we play. And sometimes the ball runs over the fence and then the guard would come down and get it. He liked it so much.” [5]

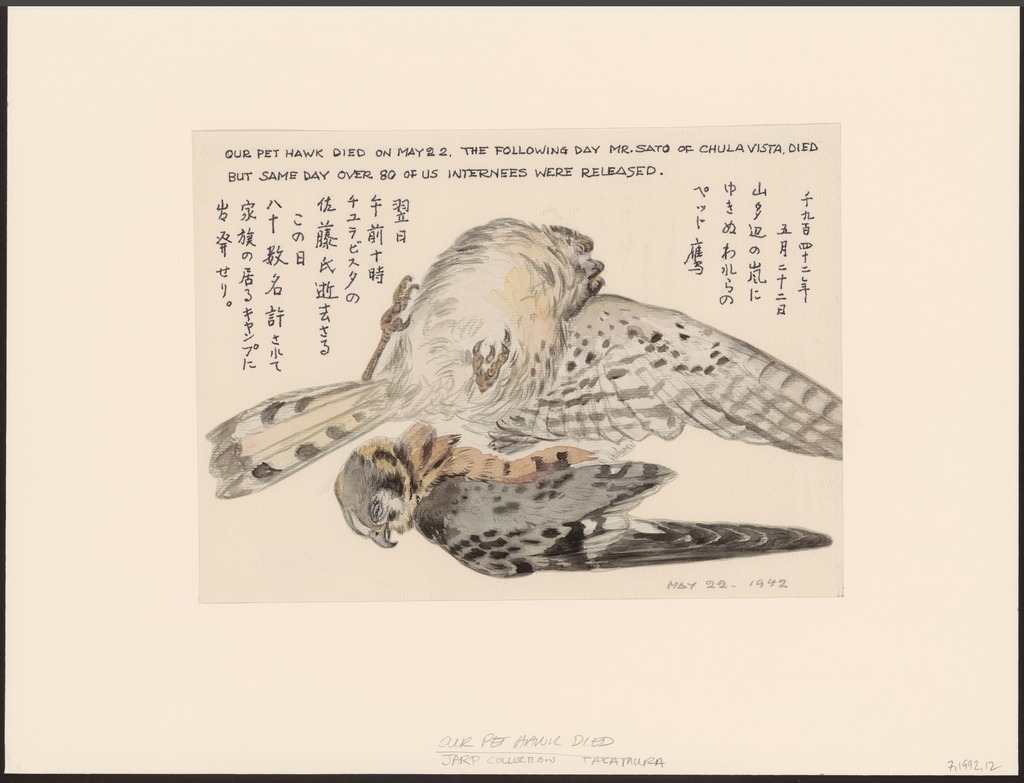

Takamura also saw symbolism and beauty in the natural world.

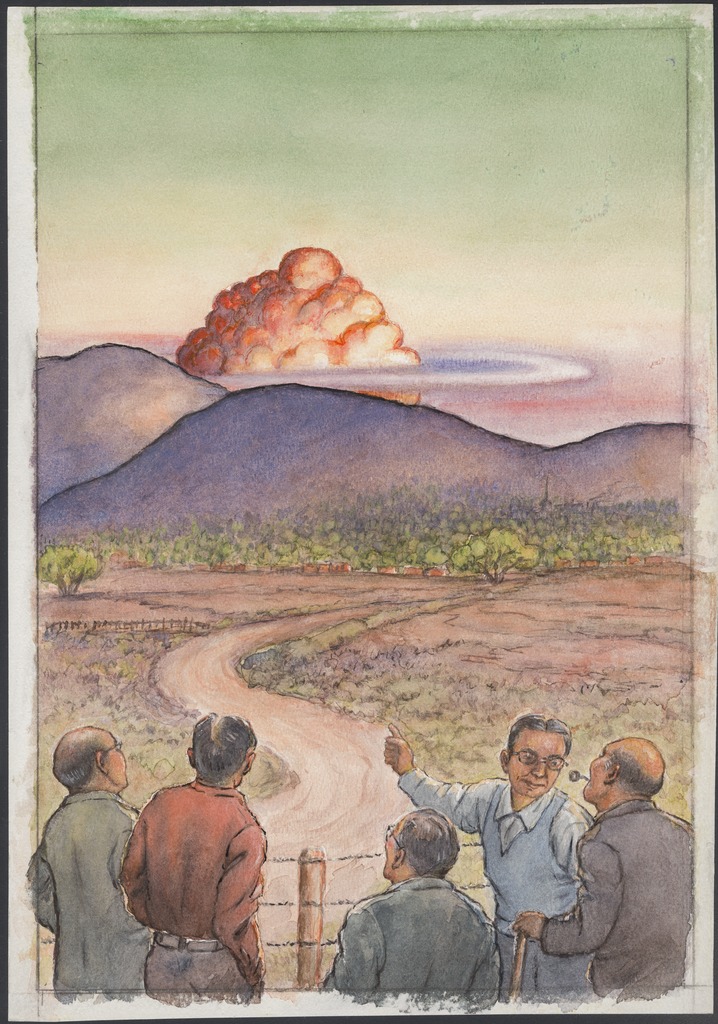

“One day we saw a wonderful cloud to the South. It was evening time. Oh, it was a big cloud. All pink. I had never seen this kind of cloud before. Really I was surprised. So we called it a ‘lucky cloud.’ ‘Look at that cloud. It won’t be long, this war,’ we said. So everybody was very happy.”[6]

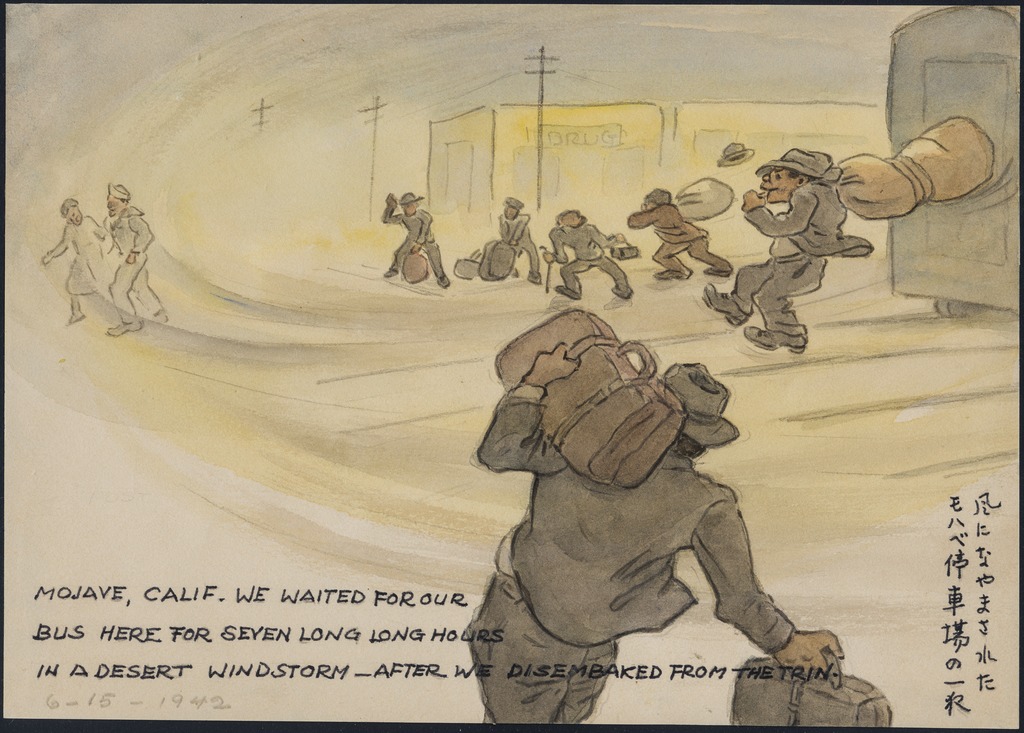

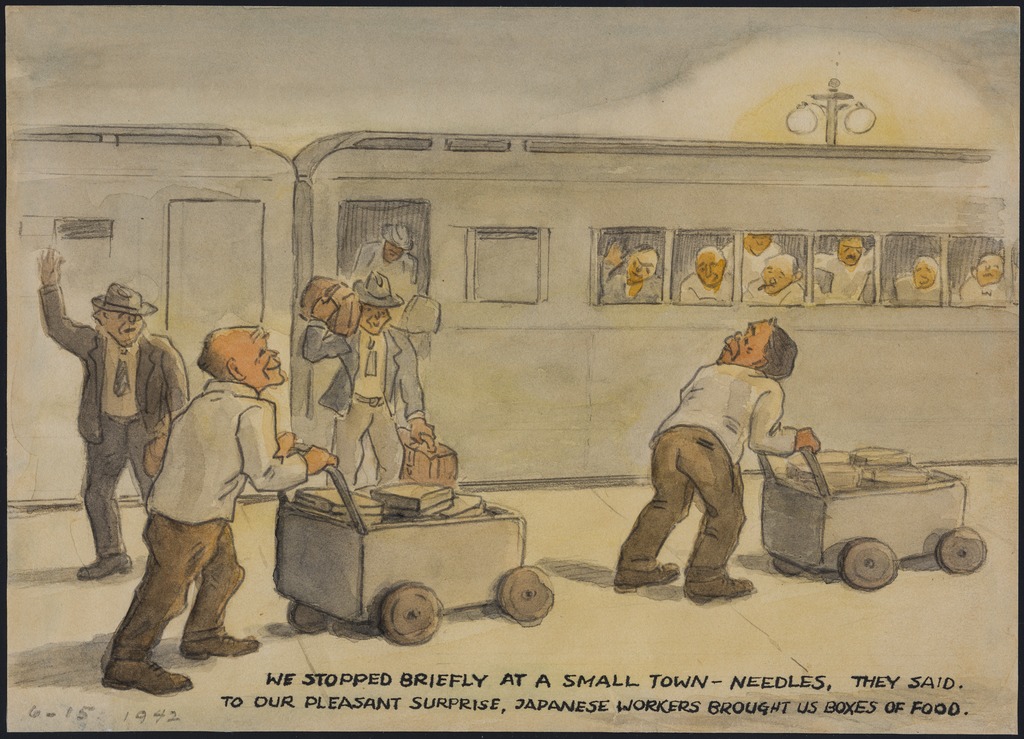

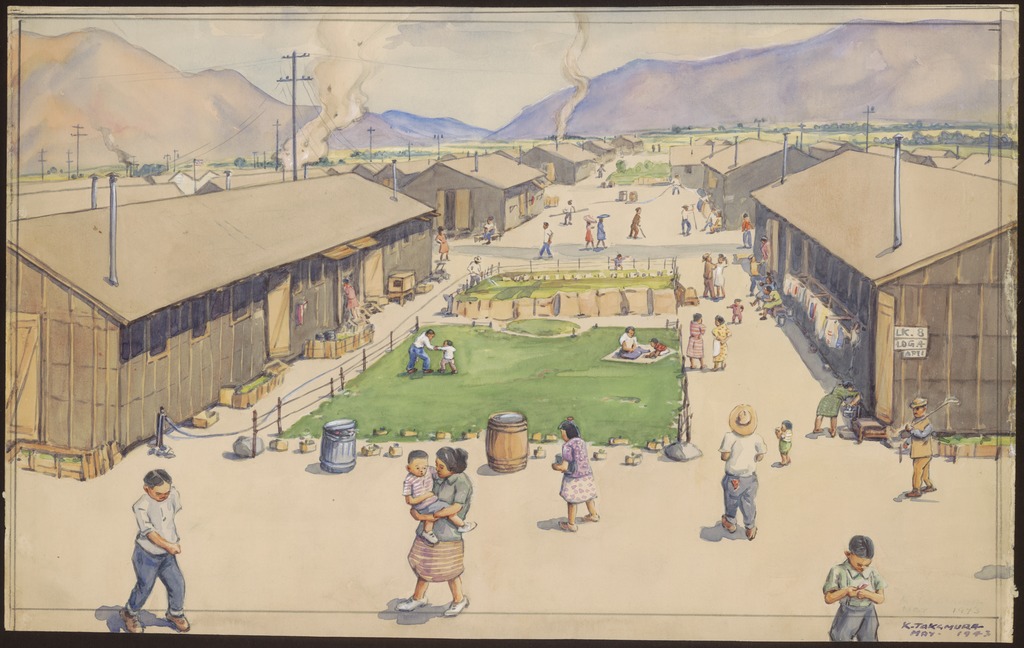

After several months at Santa Fe, Takamura was relocated to the War Relocation Authority camp at Manzanar, California. He was reunited with his wife, daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter, and remained there until the war ended in 1945. Takamura documented his travel from Santa Fe to Manzanar concentration camp.

Takamura recalled the beautiful mountains surrounding Manzanar, but also that it was hot and windy. “It is miserable, really,” he said. But after a year, more shade trees had grown and camp infrastructure had been developed. He adapted to camp life, continued making art, and took on a post as the head of a small camp museum. Years later, Takamura spoke almost fondly of his time in the concentration camp, calling it “peaceful” and “not so miserable.”

Takamura’s deep sense of patriotism sometimes drew the ire of his fellow prisoners. After a snowstorm had lodged the door to his family’s barrack shut, he remembers thinking, “I thought maybe people had nailed down the door. I thought that because some people thought my family was too much pro-America.” [7]

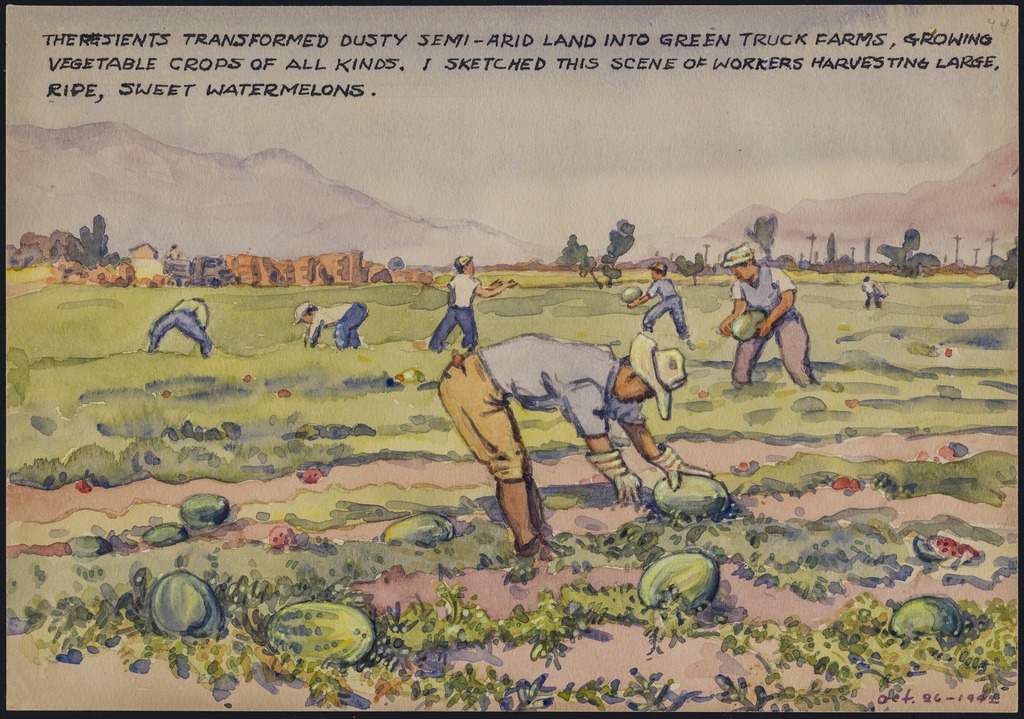

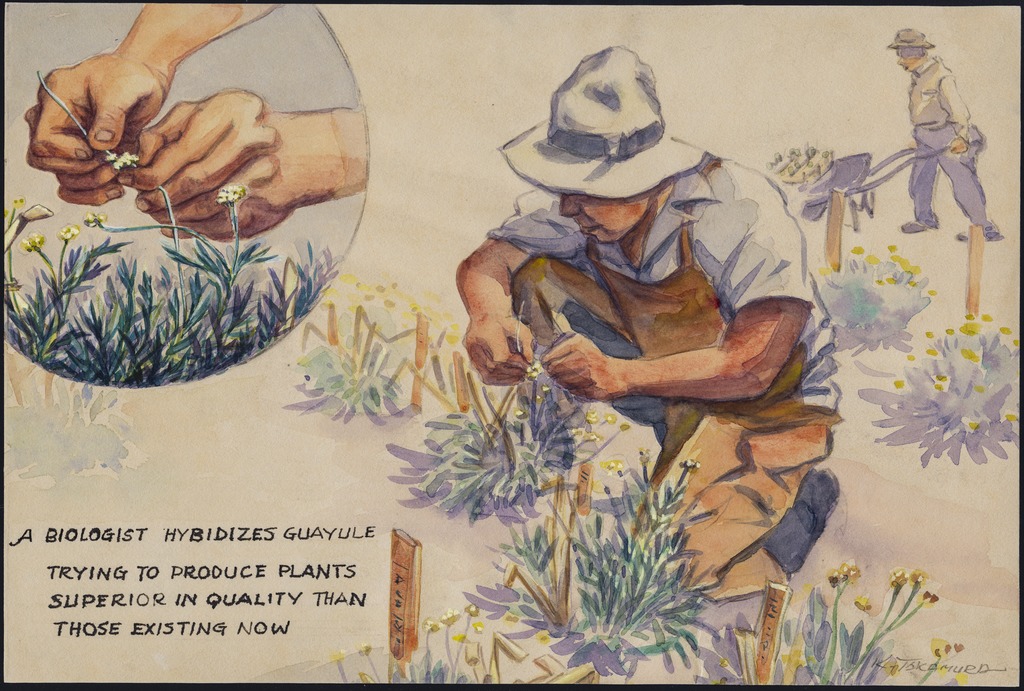

The majority of Takamura’s paintings and sketches reflected daily life at Manzanar, from school to agricultural production to special occasions.

“This was a very happy day for me, pounding mochi. We have to have mochi on New Year’s Day. Every family does. So this was a very happy day.” [8]

After the war, Takamura returned to Los Angeles and resumed his post at RKO Studios. He remembered, “I came back to RKO Studios after the war and people were really surprised to see me. I’m retoucher, you see, and the president usually never says, ‘Good morning’…but when I came back to the office, the manager and the president came to my place and welcomed me back. Twenty-five years I continued to work over there, until 1957 when they closed the studio.”

Takamura lived in Los Angeles until he passed away in January 1990 at age 94. Despite the discrimination and hardship he suffered in his lifetime, he remained unflaggingly optimistic about America. At 88 he said, “I enjoy this country so much. A nice life, I had.”

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communication and Public Engagement Manager

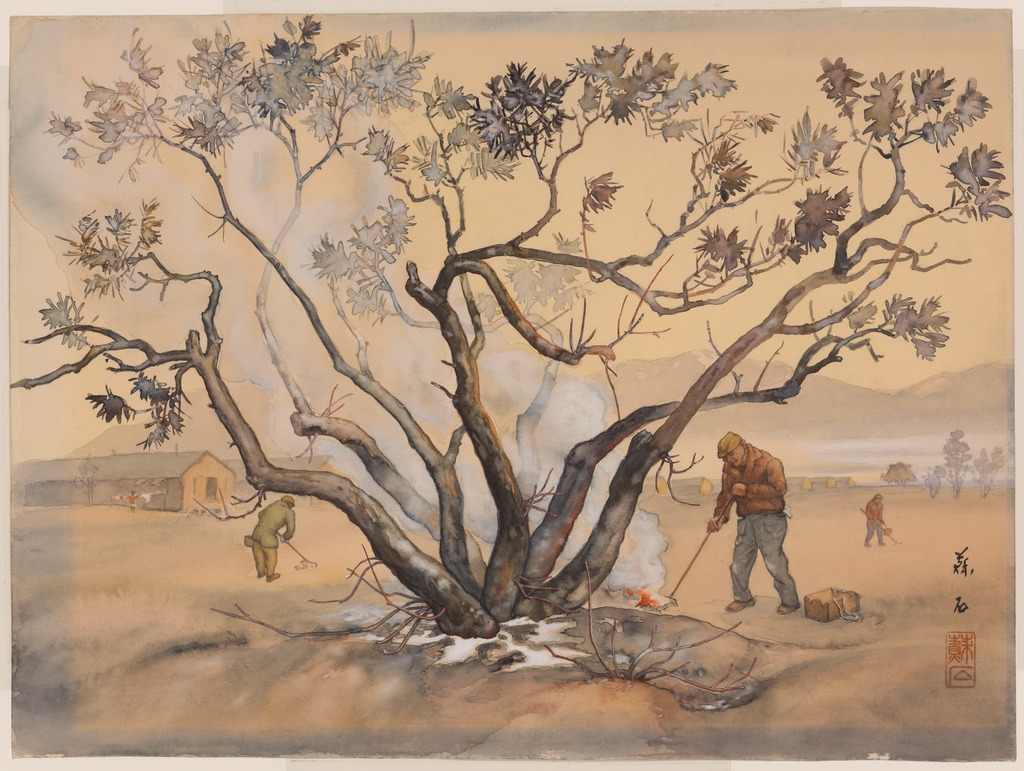

[Header image: “Keeping the camp clean and tidy.” Manzanar concentration camp. Courtesy of Manzanar National Historic Site and the Kango Takamura Collection.]

All images by Kango Takamura. View the full Kango Takamura Collection.

1. Beyond Words: Images from America’s Concentration Camps, Deborah Gesenway and Mindy Roseman (Cornell University Press, 1987), 125.

2. Ibid., 128

3. Ibid., 118

4. Ibid., 120

5. Ibid., 120

6. Ibid., 122

7. Ibid., 126

8. Ibid. 126