September 11, 2023

In this photo essay, Densho’s communications and public engagement director Natasha Varner shares images and some of what she learned during a two-week immersive learning experience about Japanese Canadian internment history this past summer. The field school included a bus tour through interior British Columbia hosted by the Nikkei National Museum and then a seminar at University of Victoria through the Past Wrongs, Future Choices program. This is just the start of what we hope will be more Densho offerings about the Japanese Canadian internment* experience in coming years.

Much like in the US, Japanese Canadian internment didn’t materialize overnight. It was the culmination of decades of anti-Asian racism that included everything from discriminatory laws to violent mob attacks, most notably Vancouver’s 1907 “race riot.” Although both Issei and Nisei were denied the right to vote in Canada, many had become naturalized British subjects so that by the time of the Pearl Harbor attacks, three quarters of the Nikkei population was either naturalized or native-born Canadians. But that status did not protect them from egregious acts of state violence.

After Pearl Harbor and a December 1941 Japanese attack on British territory in Hong Kong, Canada’s federal cabinet used the War Measures Act of 1914 to enact a series of policies, many of which were inspired by BC politicians under the leadership of Ian Alistair Mackenzie, an open white supremacist and anti-Japanese cabinet minister from British Columbia. As long as the War Measures Act was in effect, the drastic measures could not be legally challenged.

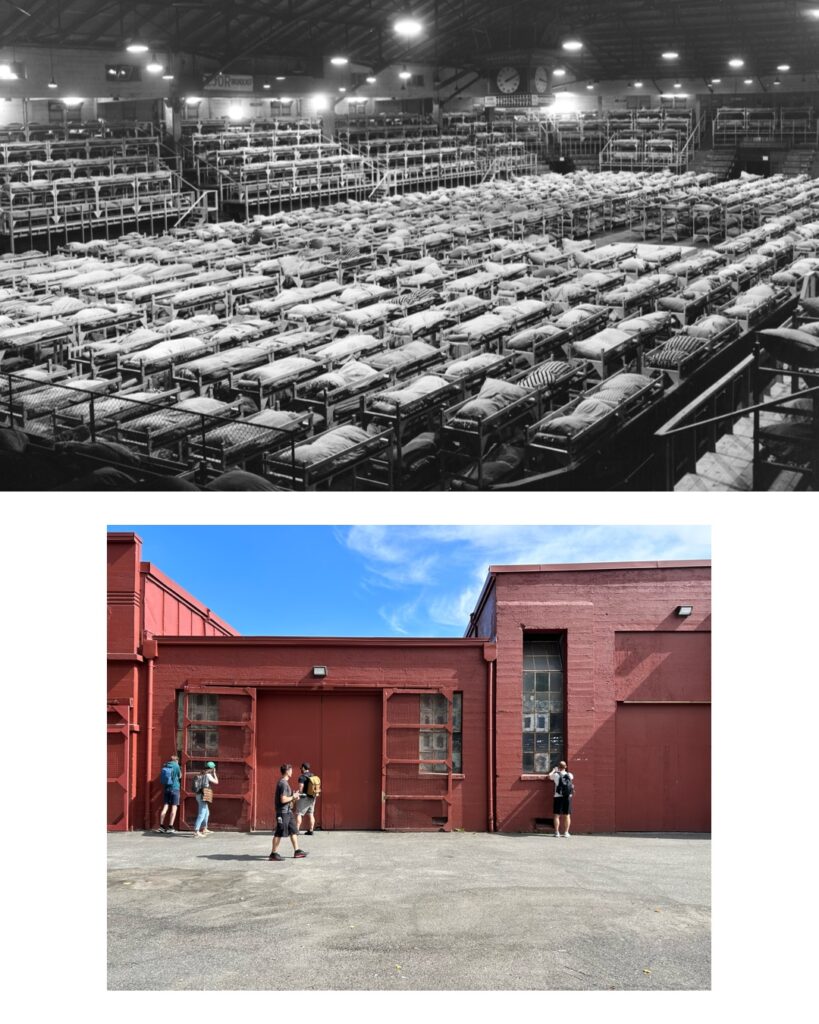

Caption: Hastings Park, where some 8,000 Japanese Canadians were packed into converted fairground buildings and forced to live in squalor for months on end while they awaited longer term placement. Oral history accounts often mention the terrible noise and smell, and complete lack of privacy. Historic photo shows the interior of the men’s dormitory, courtesy of the Nikkei National Museum Alex Eastwood Collection 1994.69.3.18. Contemporary photo taken outside the old livestock building where women and children were temporarily forced to live in unsanitary conditions.

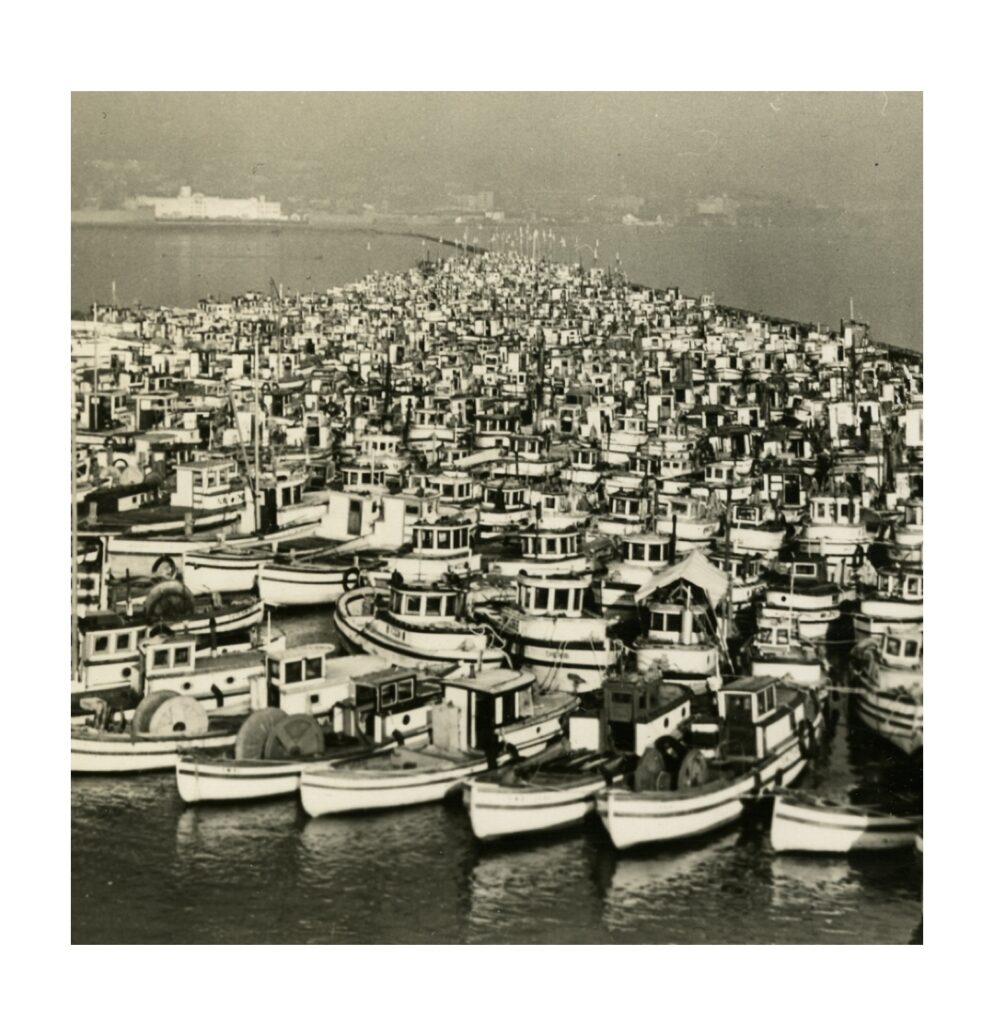

Caption: Confiscated fishing boats in the once-thriving Japanese Canadian fishing village of Steveston, at the mouth of the Fraser River. The boats were stored so haphazardly that many sustained serious damage and were either destroyed entirely or sold off at a fraction of their value. Image of impounded fishing vessels courtesy of Nikkei National Museum Kishizo Kimura Collection 2010-4-2-1-11a.

Beginning in January 1942, Nikkei men within a 100-mile radius of the coast of British Columbia between the ages of 18 and 45 were rounded up and sent to forced labor camps – euphemistically called “road camps” – where they had to engage in grueling highway construction. BC politicians – particularly Ian Mackenzie – didn’t stop there. They continued to advocate for the removal of all Japanese Canadians and on February 26, 1942 their vision came to pass in the form of an Executive Order closely modeled off of EO9066.

Within a matter of weeks, the forced removal of all Nikkei residents of British Columbia began. Japanese Canadian women, children, and the men who had not already been forced into labor camps were given as little as 24 hours notice to pack their belongings and leave their homes. Many were then forced to live in overcrowded squalor in a massive fairgrounds-turned-detention facility – Hastings Park – in Vancouver.

They were then funneled to different types of camps depending on their circumstances: Around 12,000 were sent to internment camps in interior BC, many of which were situated in repurposed ghost towns or on lands leased from farmers. Some families were able to reunite by “volunteering” to work on sugar beet farms in Alberta and Manitoba. And those with enough savings on hand and the right connections were permitted to establish “self-supporting” camps or relocate to live with family in eastern Canada.

Their trials didn’t end there. Beginning in 1943, Japanese Canadians were systematically dispossessed of their property by the Canadian government. Homes, farms, businesses, and other possessions were sold – often at a fraction of their value. The funds were then placed in government-managed accounts and doled out in tightly restricted monthly stipends which internees had to use to pay for basic necessities in the camps. This scheme – which Ian Mackenzie also masterminded and advocated for – served to deter Japanese Canadians from ever returning to the West Coast and provided jobs and housing for white Canadians, particularly veterans. As Masumi Izumi writes in the Densho Encyclopedia, “The Canadian government systematically deprived Japanese Canadians of their property, and effectively made them pay for their own incarceration.”

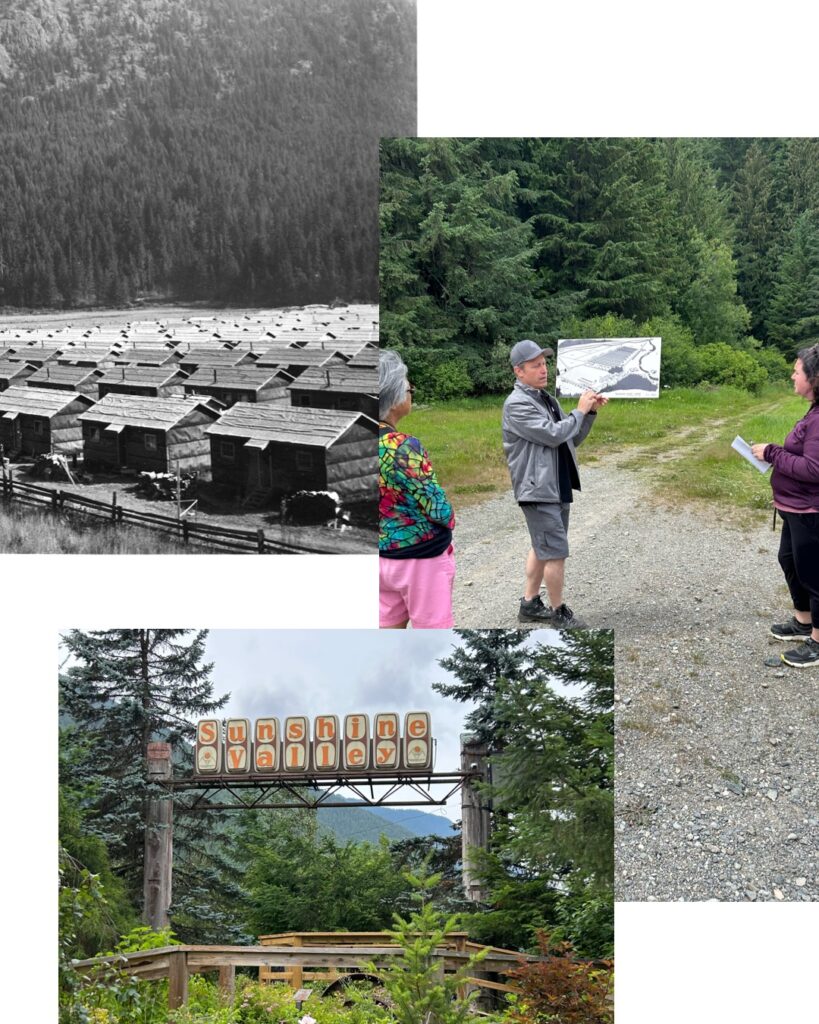

Caption: Tashme, the largest and most isolated of the camps in what’s now called Sunshine Valley. Now a small museum and the Tashme Historical Project is housed in what was once the butcher shop and an 80-year old gobo plant grows outside a replica barrack. Historic photo of Tashme courtesy of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre. Contemporary photos show Tashme museum founder and curator Ryan Ellan giving a tour of the site to bus tour participants and a sign that marks the entrance to Sunshine Valley, the former site of the Tashme Internment Camp.

Caption: Fellow members of the bus tour listen to a talk at the Nikkei Legacy Park in Greenwood, BC. Greenwood was an abandoned copper mining town in 1942. Catholic clergy welcomed many fishing families from Steveston who were trying to keep their families intact and provided education to the children for the duration of the war. Many Japanese Canadians stayed in Greenwood after the war, helping to reverse the economic and social decline that had preceded their arrival.

Caption: There are no visible remains of Lemon Creek, which was once the second largest of the camps with a population of 1,851. Lemon Creek was one of four detention sites in the Slocan Extension, where the BC government leased pastures and farmlands on which Japanese Canadians were made to build their own shacks and cities to sustain them. Historic photo of Tsusano Baba and Jack Baba seated on a garden fence at Lemon Creek; courtesy of Nikkei National Museum Frank Baba Collection 2013.9.1.2. Contemporary photo of a fellow bus tour participant walking what was once a railway that ran along the perimeter of the camp.

Caption: Some 1,500 Japanese Canadians lived in New Denver, where an impressive interpretive center, surviving barracks, and historic artifacts donated by the families that once lived here help make the history of what was once here feel more tangible. Our guide at the museum, Ruby, talked about why Japanese Canadians continued living in New Denver long after the war: “They stayed and they stayed and they stayed until 1957,” she said, “because they had nowhere else to go and because they had each other.” Photos show barracks and artifacts from the camp at the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre.

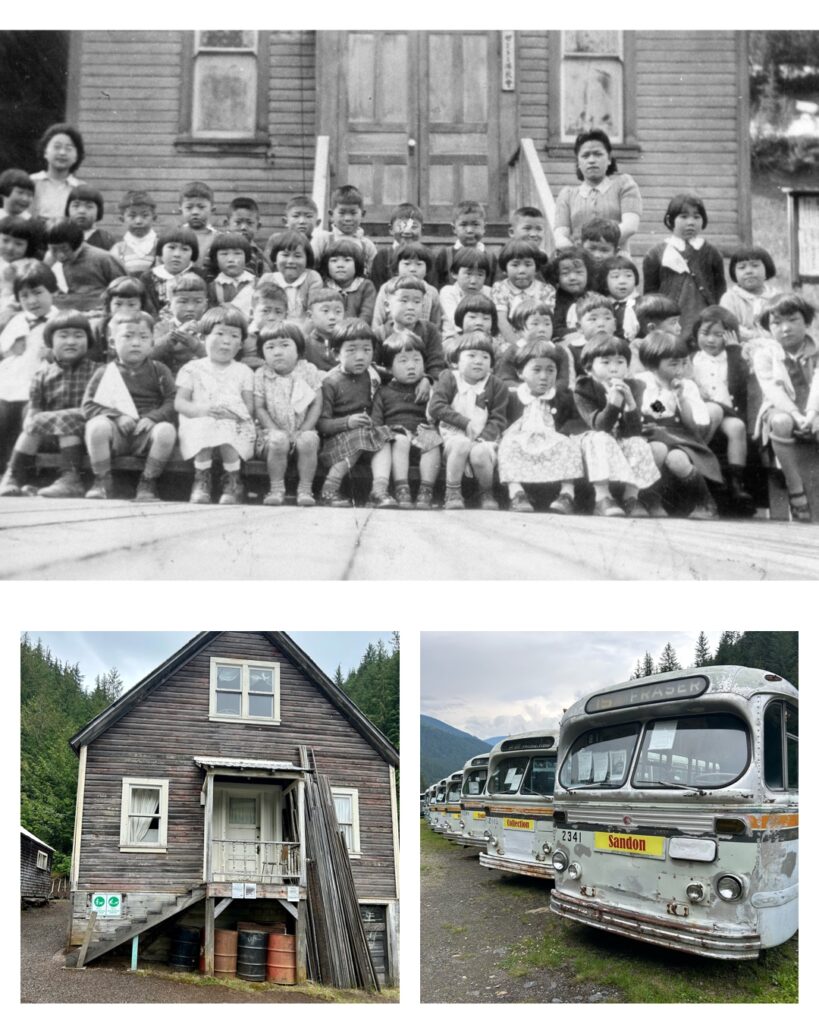

Caption: Sandon is nicknamed the “Sunless City.” It’s a mostly abandoned ghost town situated in a narrow valley between two steep mountains prone to rockslides and cloaked in damp gloom even at the height of summer. During the war, its population swelled from 20 to nearly 1,000 mostly elderly Japanese Canadians who renovated and rebuilt buildings that had been abandoned after the town’s 19th century silver mining boom had ended. Historic photo shows children posing in front of a building in Sandon, BC. The teacher in the top right corner is Lillian Nishikawa; she taught Sunday school and played the piano at the Buddhist church, courtesy of Nikkei National Museum and the Sakamoto Family Collection, 1993.34.9.a-c. Contemporary photos show a building in present-day Sandon and a row of salvaged Vancouver trolley buses now being stored in the town.

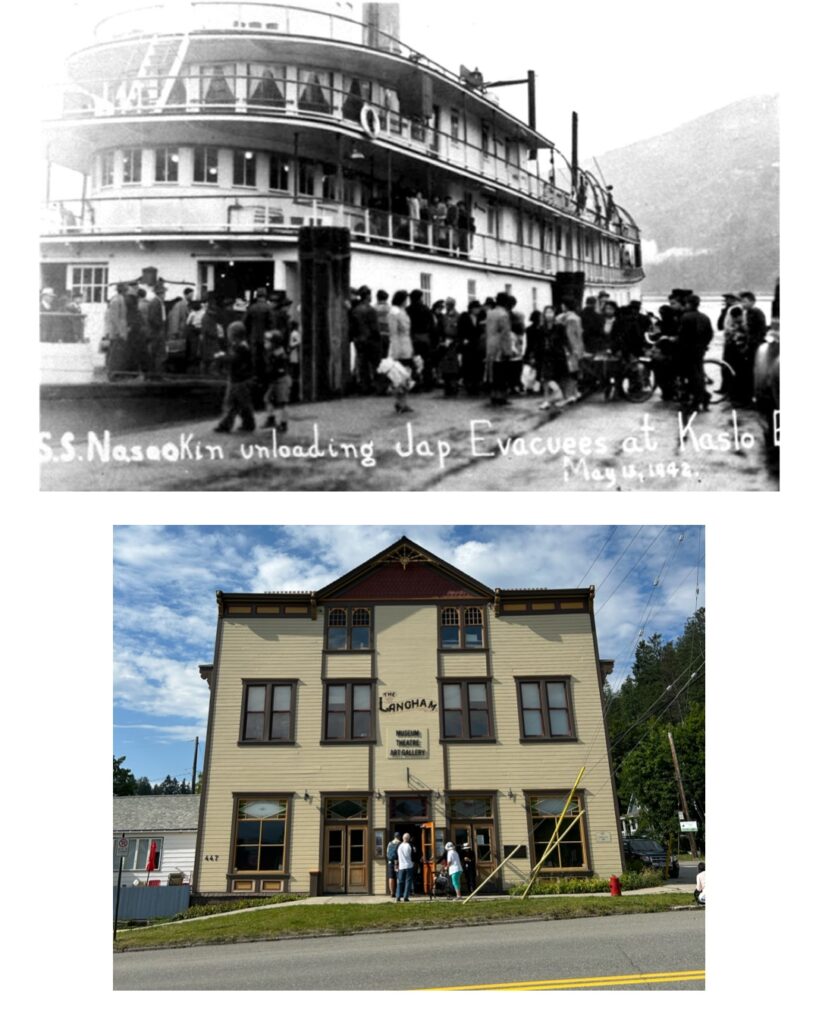

Caption: Kaslo, another ghost town camp where nearly 1,000 Japanese Canadians lived during WWII. The only Japanese Canadian newspaper that was allowed to be published during the war, The New Canadian, was published out of Kaslo. The offices and printing press were housed in what is now a natural foods store. Around 80 Japanese Canadians lived in The Langham, pictured here, during WWII. The building later fell into disrepair but now houses a small museum and performance space. Historic photo shows a steamer docked at a pier on Kootenay Lake with Japanese Canadian men, women and children walking off at Kaslo, courtesy of the Nikkei National Museum Kumano Family Collection, 2011.19.15. Contemporary photo shows bus tour participants outside the present-day Langham Cultural Centre and museum.

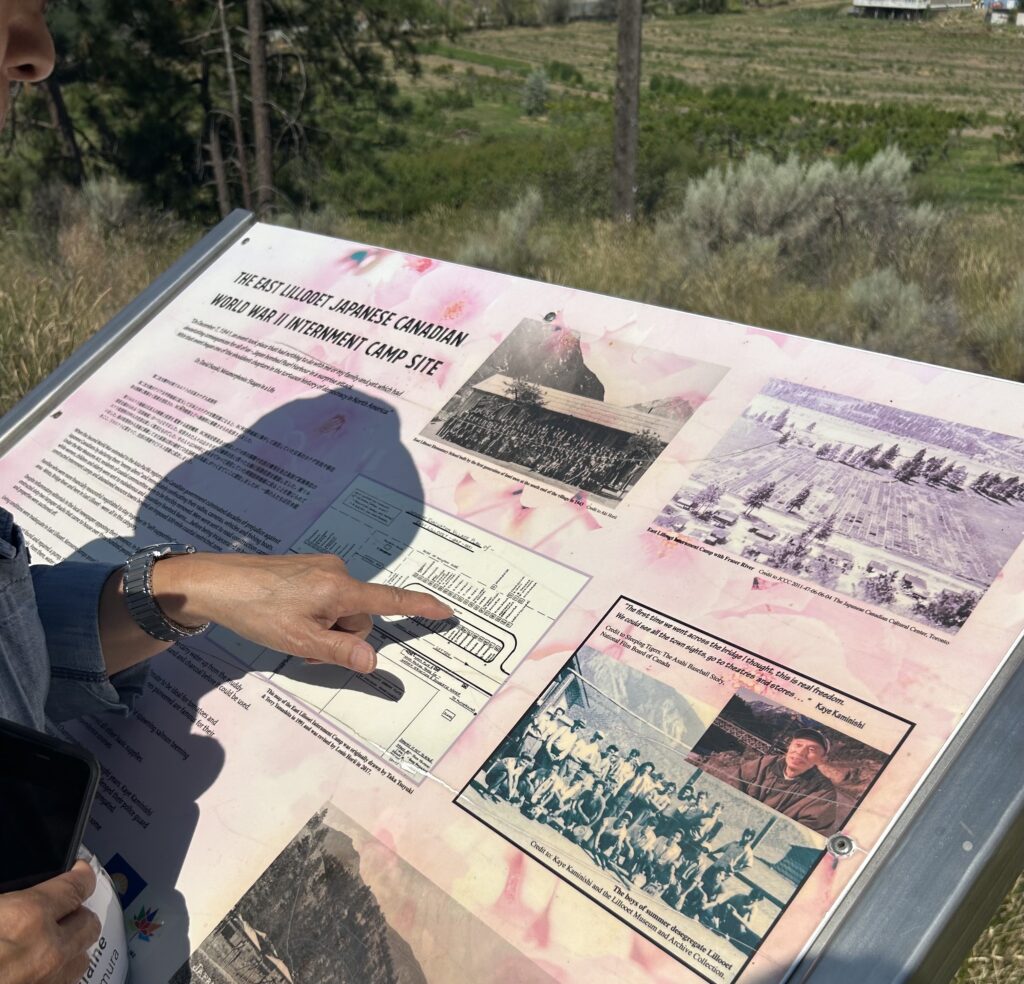

Caption: East Lillooet was a “self-supporting” camp built in the hot and arid lowlands along the Fraser River. Around 55 families who had enough resources to fully support themselves lived in tar paper shacks here for the duration of the war and into the late 1940s. In this picture, a bus tour member points to where her family’s home once stood. Her sister was also on the tour and I was able to get to know her over several hours of sitting on the bus together. She had also just suffered the loss of her husband – this was the first trip she’d taken without him, and her first time returning to East Lillooett since being born there in 1947. She later told me that she wanted to share more with the group, but that “the emotions just get too piled up.”

In December 1944, the Canadian government made all internees fill out a repatriation form. Like the highly divisive and misguided “loyalty questionnaire” in the US, this form was both confusingly worded and immensely consequential. It presented Japanese Canadians with two undesirable options aimed at ensuring their permanent removal from the West Coast: immediate relocation to east of the Rockies or postwar “repatriation” to Japan (in reality, this was a deportation to a foreign, war-ravaged land for most respondents).

The anguishing decisions about how to respond to this form were made under such extreme duress that they can barely be called decisions at all. And yet they had immediate and long-lasting consequences for the lives of Japanese Canadians. Many of the 10,000 who had chosen “repatriation” attempted to revoke their repatriation applications when Japan surrendered in August 1945. They were at first denied and then, under mounting public pressure, permitted to maintain their Canadian citizenship.

Ultimately around 4,000 Japanese Canadians were deported and stripped of their citizenship under this system. Thousands of others were “dispersed” East of the Rockies in a deliberate attempt to prevent their return to the West Coast and to isolate Japanese Canadians from their communities. This is known colloquially as the “second uprooting.” The exclusion orders were finally lifted in 1949, but the impacts of years of uprootings, dispossession, deportation, and dispersal left lasting wounds. The 1970s saw a cultural resurgence and a redress movement much like that in the US. A month after the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was signed, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney signed a redress bill that included a formal apology as well as $21,000 to survivors, recovery of Canadian citizenship to those who had been deported, and educational funds.

These are just the broad strokes of a long and complicated history. Within this overview are thousands of stories of heartbreak, of hopelessness, of resilience, and of resistance. I hope to take all that I learned during my time in BC to help bring some of those stories to Densho’s audiences, but I want to do this with extreme sensitivity to ongoing conversations among Japanese Canadians about who is telling this story and how it is told.

As I reflect back on the bus tour and look ahead to the role that Densho might play in sharing this story, I’m humbled and enormously grateful to the community of people I was able to learn from and alongside during the field school. At times, I’ve found myself comparing what I know of Japanese American incarceration history to what I learned on this trip but ultimately I think that’s an impossible calculation – the Japanese Canadian wartime experience wasn’t better or worse than the Japanese American experience, it was simply different. Both constituted large scale violations of human rights and, as with other dark parts of our history, the question we ask shouldn’t be who had it worse, but rather: what responsibility do we all have in making sure that nothing like this ever happens again?

–

Text and photos by Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director

*Terminology note: “internment” is still dominantly used in Canada, so I’m using that here even though Densho’s preferred terminology is “incarceration.”

Sources and further reading:

Karizumai: A Guide to Japanese Canadian Internment Sites by Linda Kawamoto Reid and Beth Carter

Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre

The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians During the Second World War by Ann Gomer Sunahara

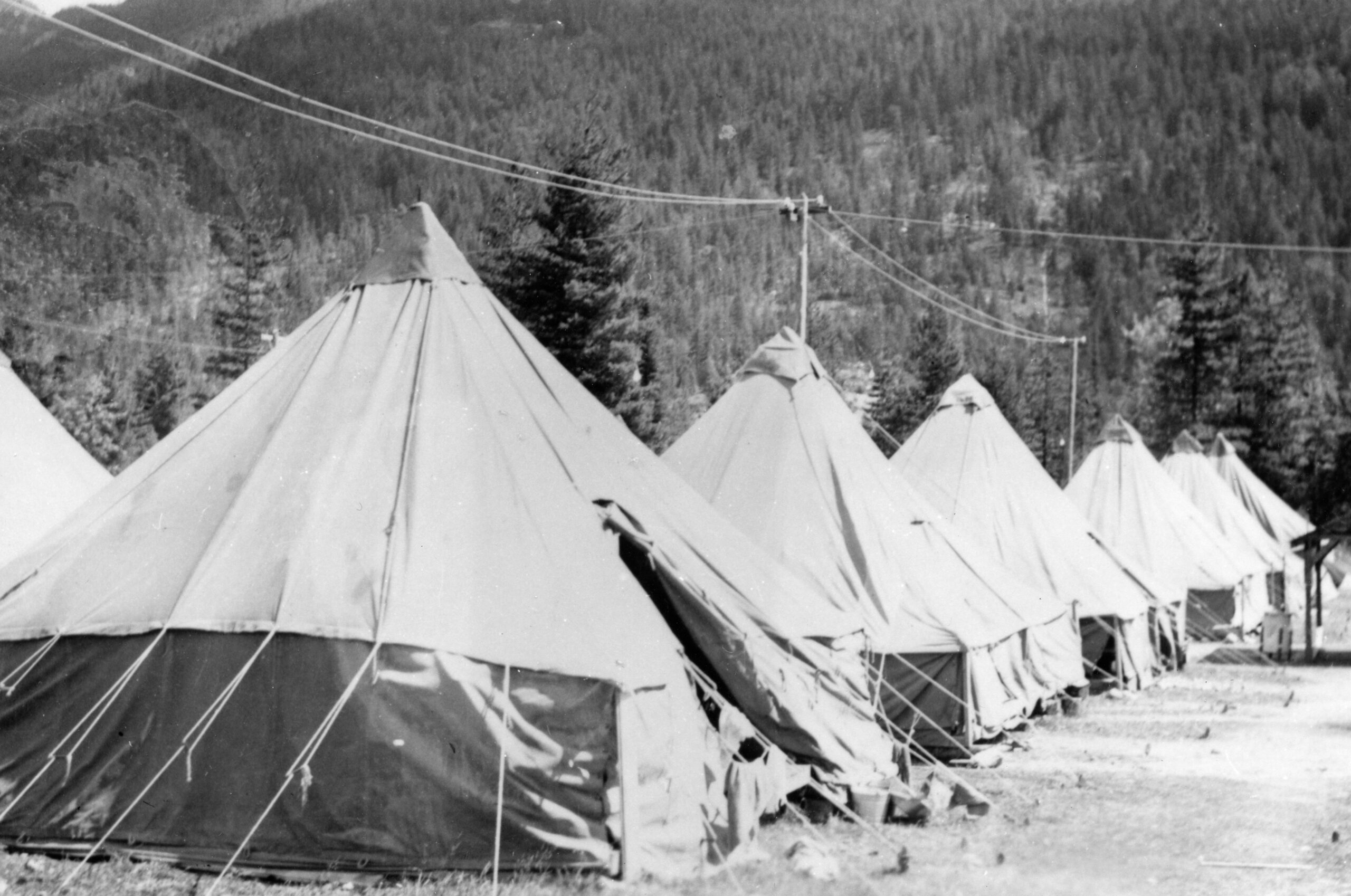

[Header image: Tents where Japanese Canadians were housed in Slocan, BC. Courtesy of the Nikkei National Museum 1992.11.1.a-c.]