September 12, 2017

Fairgrounds in Fresno, Merced, Pomona, Puyallup, Salinas, Stockton, Tulare, and Turlock have a dark common history. Seventy five years ago, they served as sites for the temporary detention of Japanese American men, women, and children. The fairground detention sites mostly housed Japanese Americans from rural areas and were part of a larger network of assembly centers run by the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA). They were quickly transformed into prisons intended to hold detainees while more permanent concentration camps were being readied in desolate spots across the country. But even in their impermanence, fairground detention facilities hold painful and enduring memories for many Japanese Americans.

This month, as fair-goers flock to indulge in fried foods, games, and rides, we hope they’ll pause to remember the stories of loss and injustice that these sites contain.

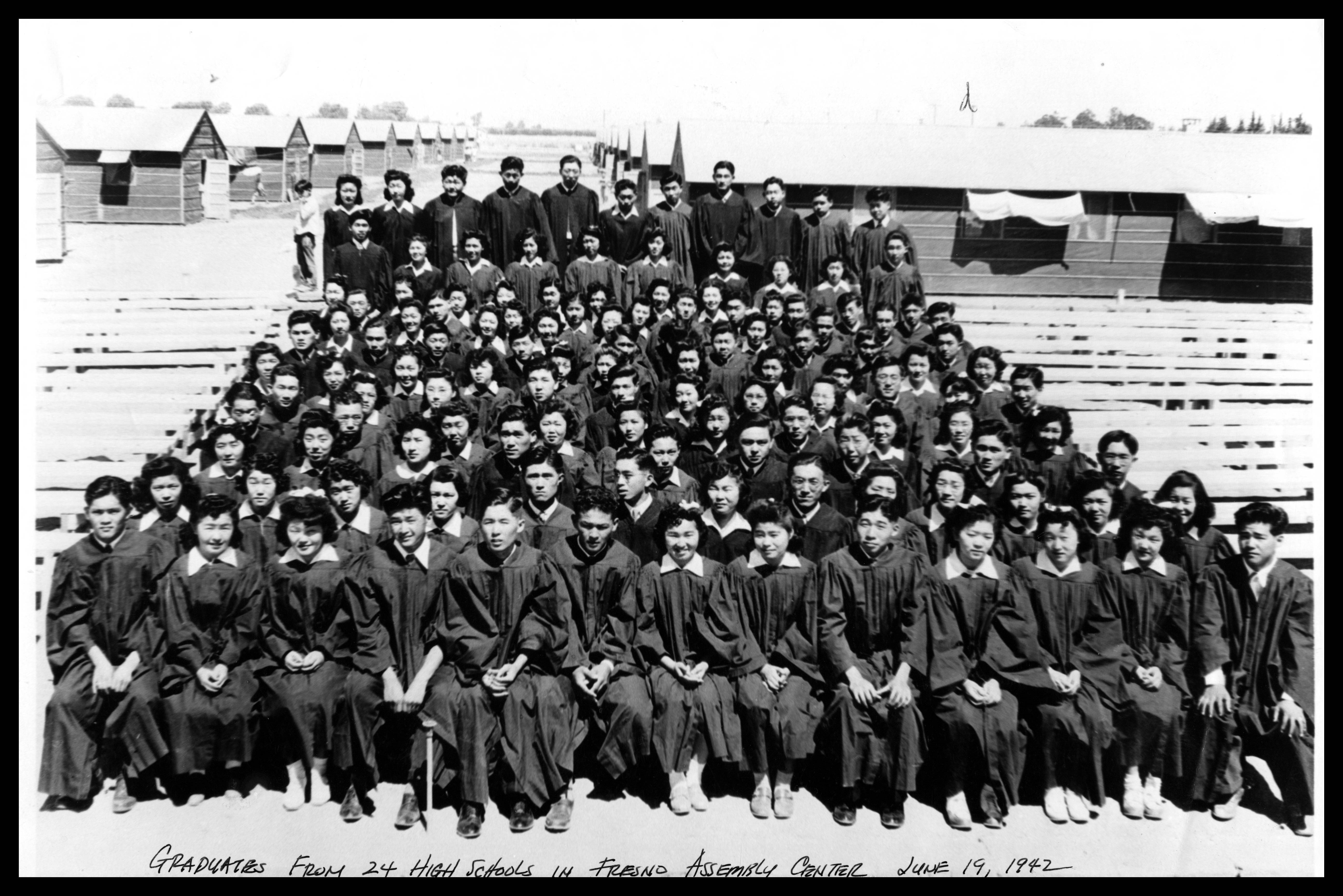

Fresno (California)

The Fresno Assembly Center was located at the Fresno County Fairgrounds just east of downtown Fresno and only about twelve miles from the Pinedale Assembly Center. The detention facility was populated from May 6 to October 30, a total of 177 days. It was last of these facilities to close. When the camp closed in October of 1942, nearly all of the inmates held here were sent to the Jerome, Arkansas camp, with the remaining handful going to Gila River, Arizona.

In his interview with Densho, Saburo Masada recalled details of life at Fresno:

“I do remember certain things that stand out, and all of us, as soon as we mentioned it everybody laughs if they can remember, and it’s the community toilets. They were just holes in a blank, on a plank, I forgot, maybe five or six, and over here [raises arm] was a big tank that’s filled with water, and when it got so full it would just tip the tank and the water would rush down, and whoever sat on the last hole there, the water would splash up. And so nobody wanted to sit there, but sometimes I guess they didn’t, they didn’t think that it was going to unload when they were there, but if it did they made sure they got up. In fact, all of us sitting, when that tank emptied out we would stand up, because the water’s gushing down. I remember early on, but then, maybe a couple, three weeks, they had a talent show going on, try to make life as normal as possible, and they had about six chairs on the stage and they pantomimed, these guys sitting there, jumping up and sitting down, jumping up and sitting down. We all knew what they were pantomiming. That was so vivid in our experience. That didn’t happen in Jerome or Rohwer; they had a little different system. But then showers were very difficult, especially for the women, since there was no privacy. That was really embarrassing and degrading for the women.”

Merced (California)

The Merced Assembly Center was located at the Merced, California Country Fairgrounds and operated by the Wartime Civil Control Administration. There were approximately 200 tar paper barracks (each 20 by 100 feet and each divided into units for five families), eleven mess halls, five laundries, forty shower areas, and thirty toilet areas. The detention facility was fenced in with barbed wire 4½ feet high. One hundred sixty soldiers guarded the prisoners. About 1,000 of the 4,669 prisoners were school-aged children, and temporary schools were set up for them.

The Merced Assembly Center was closed five months after opening on September 15, 1942. While some inmates ventured inland to do sponsored seasonal agricultural work or participated in the student college resettlement programs, the vast majority of imprisoned families were transported inland by rail car to the desolate Amache (Granada), Colorado camp where they were incarcerated for the duration of World War II.

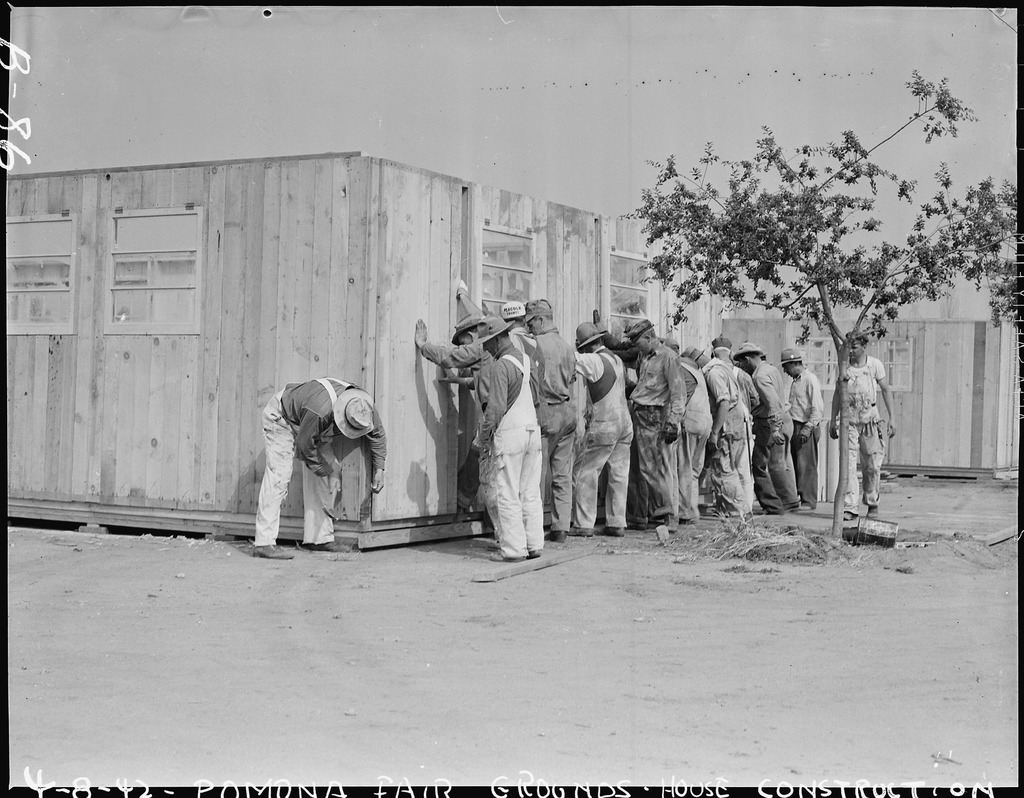

Pomona (California)

The Pomona detention facility was located at the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds (“Fairplex”) about thirty miles east of downtown Los Angeles. Two days after its official opening, 72 Japanese Americans were the first to be inducted on May 9. By May 15, the center was near capacity, holding 4,270 people. At induction, detainees were subjected to medical examination and inspections of belongings that resulted in thousands of items being confiscated. Living space per person was 73 square feet on average, well below the WCCA standard of 200 square feet per couple. The rooms were empty except for army cots and a single light bulb. According to oral history interviews, some had to live in horse stalls and sleep on straw mattresses. On July 3, the center newspaper reported that there were still not sufficient steel beds and cotton mattresses available for the sick and the aged.

Puyallup (Washington)

For two weeks beginning April 28, 1942, 7,390 Nikkei residents of Seattle and rural areas surrounding Tacoma, and a handful of Alaska residents were forcefully removed from their homes by army troops and transported into the barbed wire confines of the Puyallup Assembly Center (“Camp Harmony”), located at the Western Washington Fairgrounds in the city of Puyallup, 35 miles south of Seattle.

Units within the new barracks each had a single window cut into an eight-foot back wall, while a windowless doorway on a ten-foot front wall opened out to face another barracks. Buildings took on the appearance of long sheds. Electrical wiring ran the length of every barracks, but each apartment had only a single socket hanging from the ceiling. In each living space a wood stove sat on common shiplap floorboards.

In all, allotting 50 square feet per person as planned, the new assembly center had a capacity of just over 8,000 individuals. Many inmates who later described their accommodations recalled them as unfit for families, “nothing more than a shed on a chicken ranch,” or “rabbit hutches.”

Salinas (California)

The Salinas Assembly Center was built on fairgrounds at the north end of Salinas, a part of California’s coastal Monterey Bay area. The detention facility was populated for a total of 69 days, from April 27 to July 4. The camp was made up of 165 buildings, with barracks located north and east of the racetrack and with six buildings within the racetrack. The population of the Salinas Assembly Center came almost entirely from the Monterey Bay area. The total population was 3,608, with a maximum of 3,594. Upon the closing of the camp, nearly all of the inmates were transferred to the Poston, Arizona camp for long-term confinement.

On June 20, 1942, the facility’s newspaper, The Village Crier, reported on an Arizona send-off party darkly themed “The Last Roundup.” A mere eighty-five residents attended the event at the Salinas reception center, which had been adorned with “clever and artistic desert decorations” to “celebrate” residents’ pending relocation to Arizona.

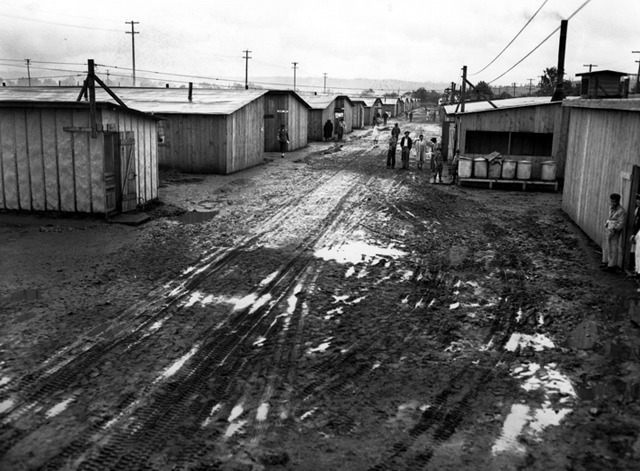

Stockton (California)

The Stockton Assembly Center was built at the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds site, just a few blocks southeast of the Stockton city center. The detention facility was populated from May 10 to October 17, 1942, a total of 160 days. The site included 125 barracks in the racetrack infield, along with forty more east of the fairgrounds. The population of the Stockton Assembly Center came mostly from the surrounding San Joaquin County area, with a total population of 4,390. Upon the closing of the camp, nearly all of the inmates were transferred to the Rohwer, Arkansas concentration camp for long-term confinement, with a handful sent to Gila River, Arizona.

In his interview with Manzanar National Historic Site, Alfred “Al” Miyagishima recalled, “The Stockton Assembly Center, that was the fairgrounds right there in Stockton, Stockton Assembly Center, and then they showed us to your barracks, and, where you were going to stay. You walk in there, and if there’s four in the family, there’s four cots there and nothing else. And I, I think there were some mattresses on the cots. We found out that there was some other friends, and so we located them, and they were housed in the stables. They had ticks, mattress ticks, ticks are mattress covers, and they had stuffed straw into those, and those were their beds. And they had whitewashed the walls and put light bulbs in ’em, but you could still smell the horses.”

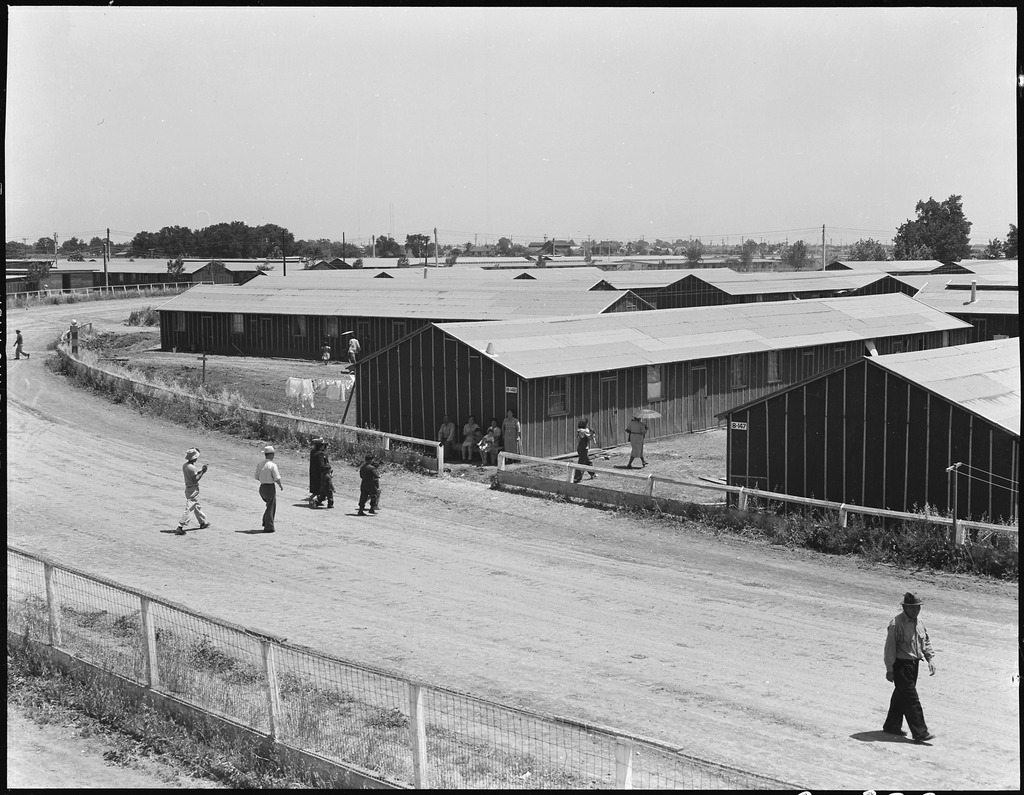

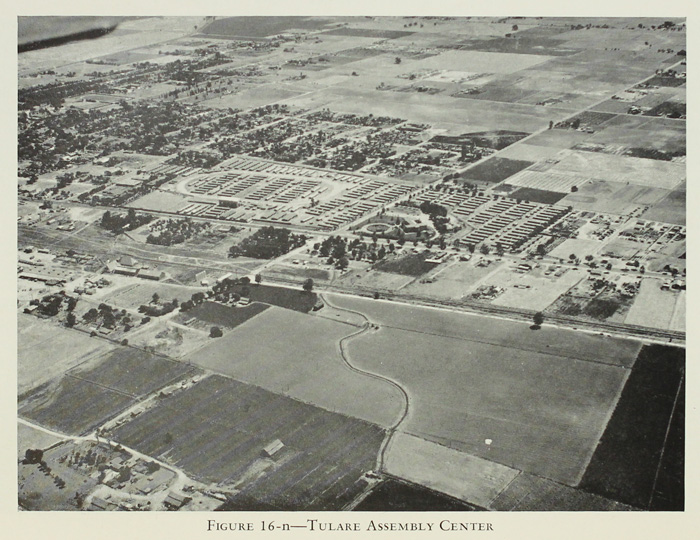

Tulare (California)

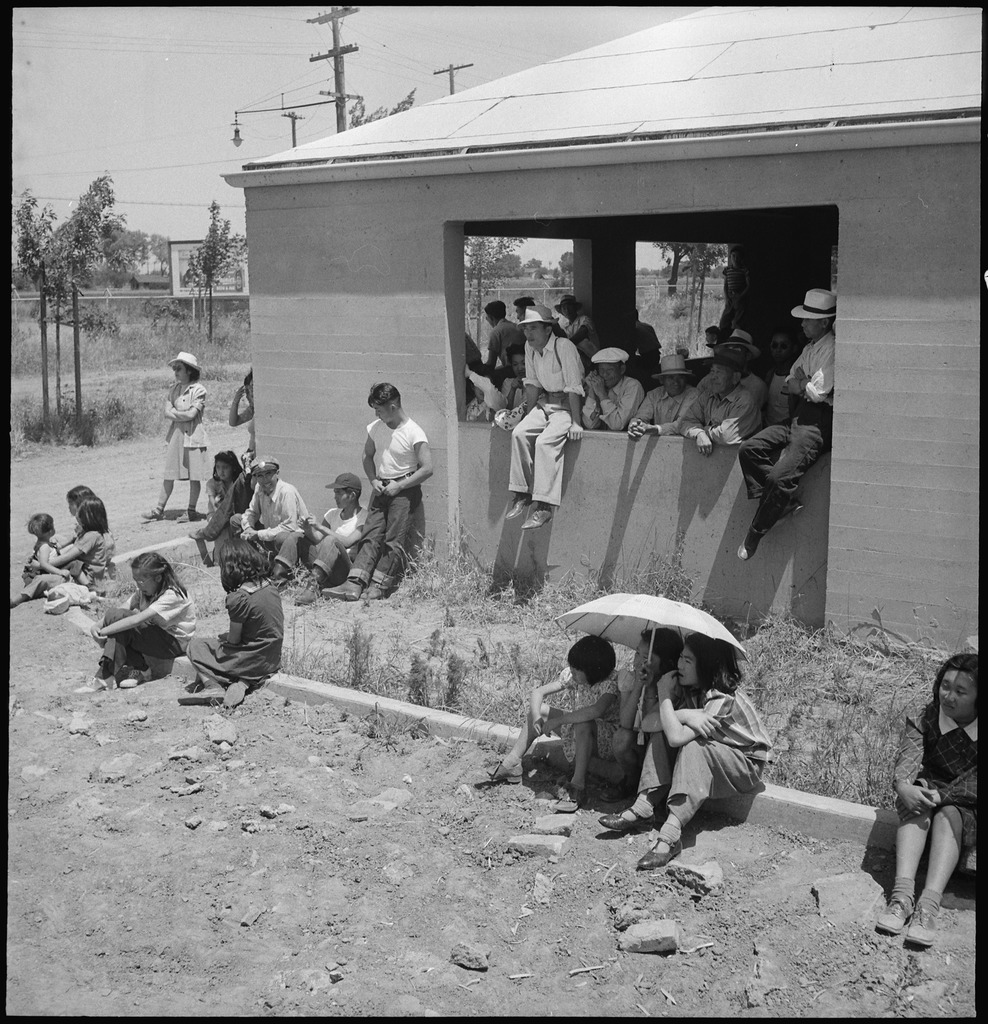

The Tulare detention facility housed residents from the coastal counties north of Los Angeles in nineteen stalls and sheds, previously used for housing livestock. The army also built an additional 152 barracks for housing, feeding, and as sanitary facilities. With one washing room for 200 persons, long lines were a common sight. “If this were designed by the Army engineers, it was certainly a crude job. I expected simple constructions […] but just ordinary common sense would have made this sort of planning ridiculous,” an inmate commented. Many mothers washed their infants in the laundry barracks, suspicious of the hygienic conditions in the washing rooms.

The hospital barracks had no medical equipment, no furniture (except the ubiquitous picnic tables and army cots), not even running water. Daytime temperatures in the barracks were between 95° and 109°F. The only thing existing in abundance was medical personnel: By the end of June four MDs, three dentists, two trained nurses, five paramedics, and forty orderlies had volunteered. Lack of medical supplies was the most serious problem, the only medication during the first weeks being aspirin. Fever and digestive problems were the most widespread medical conditions, due to the unbalanced diet and the unfamiliar heat.

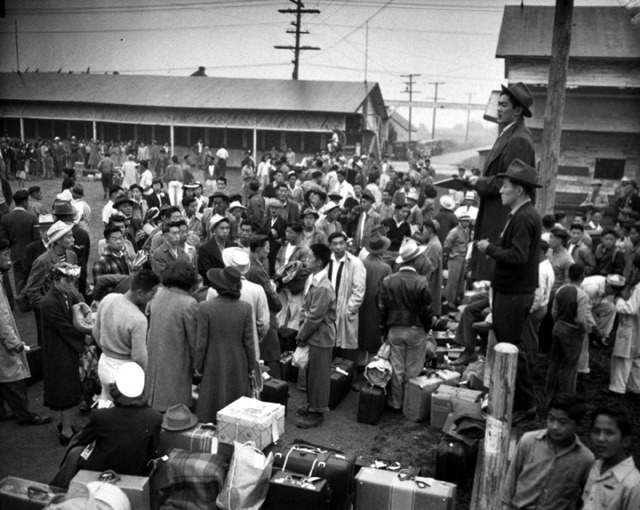

Turlock (California)

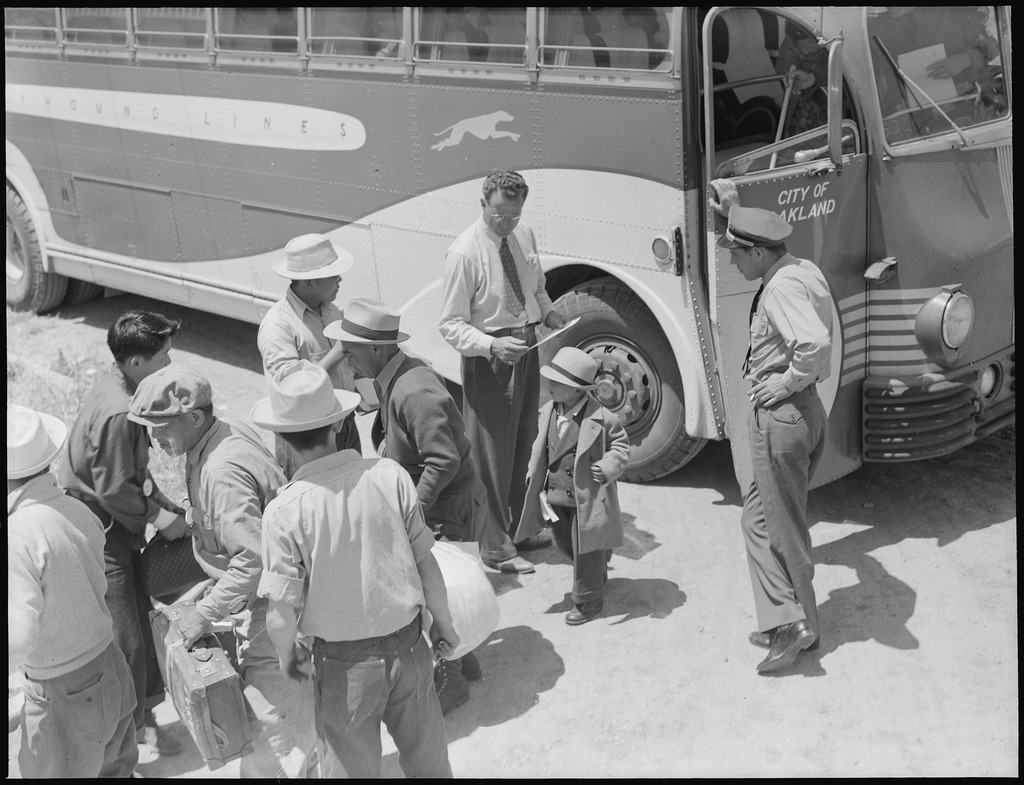

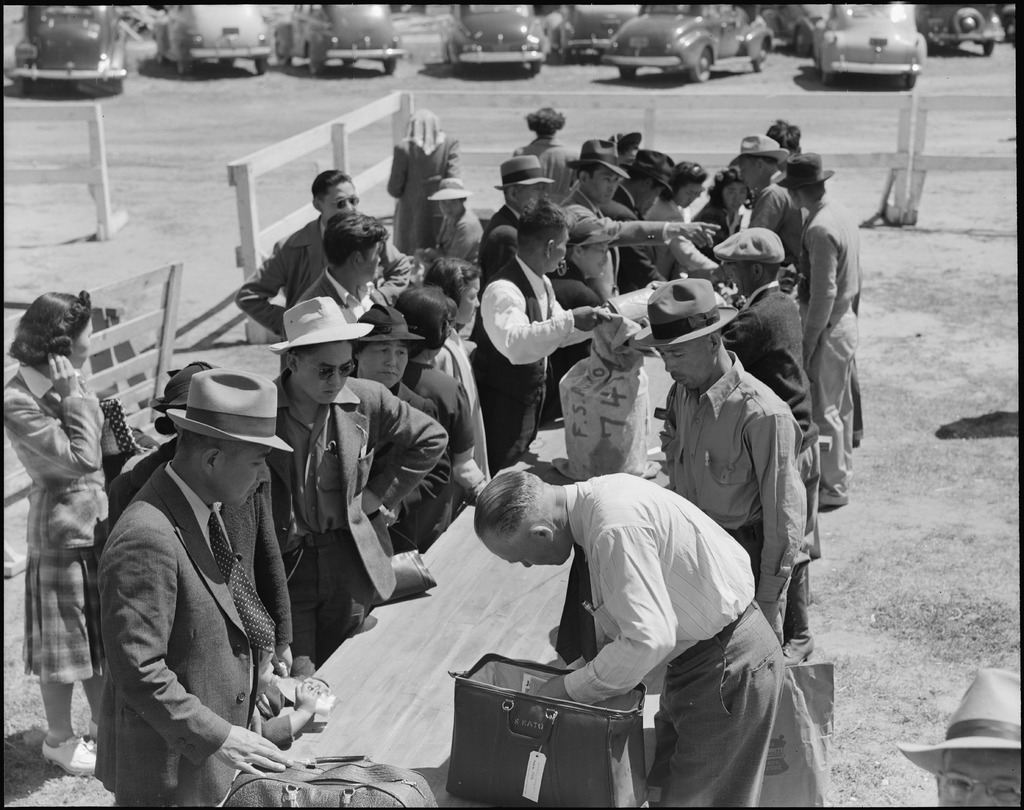

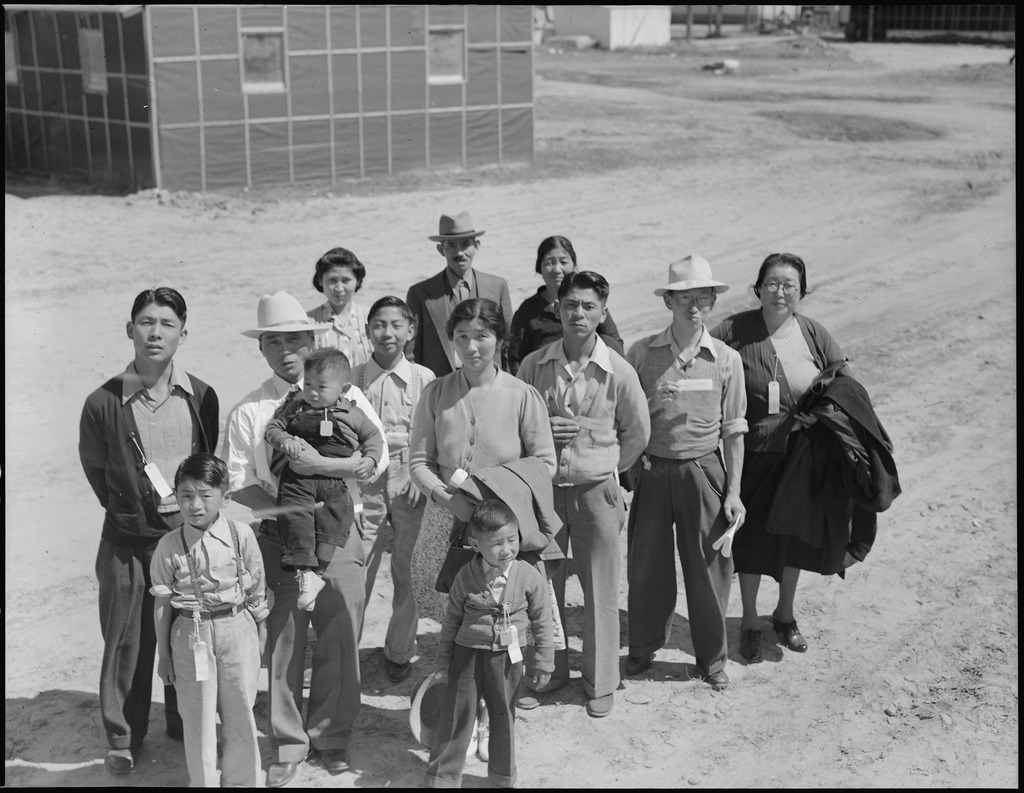

Detainees of the Turlock Assembly Center were from the Sacramento River Delta and Los Angeles regions. Dorothea Lange of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) documented the arrival of inmates through photographs on May 2, 1942. The first set of photographs was taken in Byron, California where Contra Costa County residents of Japanese ancestry were ordered to report. In Byron, crowds of people waited to board buses to make the 65-mile journey to Turlock. Individuals were only allowed to bring what they could carry, which were generally just a few suitcases.

Upon arriving at the Turlock Assembly Center, inmates were required to wait in line while their luggage was searched for contraband items. Children arriving at the center had identification tags affixed to their clothing. Once the baggage claim and search process was complete, individuals were allowed to view their newly assigned homes. The barracks were of bare and simple construction and were put together hastily. Some detainees were required to sleep in barracks that were once horse stalls. Living quarters in Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) camps were typically very bare and consisted of cots, blankets, mattresses made from straw filled sacks, and had a single light bulb hanging from the ceiling.

By August 1942, the detainees had been relocated to the Gila River concentration camp.

—

Content excerpted from Densho Encyclopedia articles by Adrienne Iwata, Konrad Linke, Louis Fiset, and Kayla Canelo.

[Header photo: Salinas, California. These evacuees, having identified their belongings which were brought to this Assembly Center by truck, are not [sic] taking it to their barrack homes. Photo by Clem Albers, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]