May 14, 2024

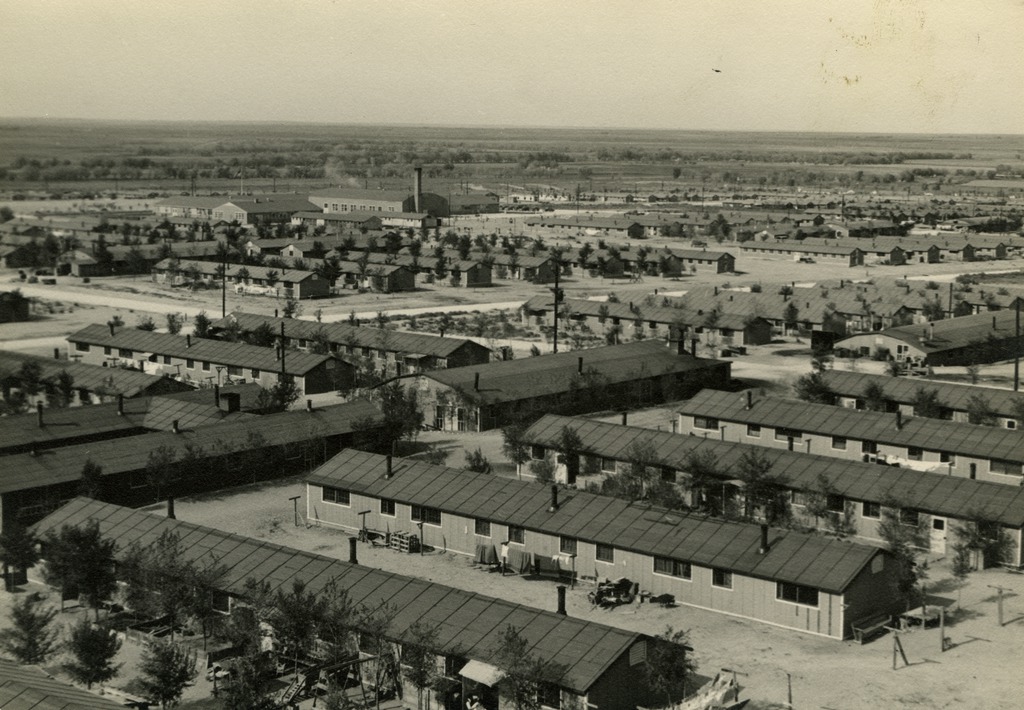

Amache was the smallest of the ten concentration camps the US Government constructed to detain Japanese Americans during WWII. Yet with a peak population of more than 7,000, the prison was big enough that it ranked as the tenth largest city in Colorado during its brief existence. And as of February 15, 2024, it’s America’s newest national park.

As survivors and descendants head to Amache this week for the annual pilgrimage, we take a look back at the site’s history as seen through the lens of photographer George Ochikubo. Native to Portland, Ochikubo arrived at Amache in 1943 — likely one of the 993 transfers from Tule Lake — and brought with him his 4×5 speed graphic camera.

With a keen eye for capturing the natural world, Ochikubo’s collection includes numerous nature photos and many images that frame Amache and its incarcerees as being dwarfed by the environment that surrounded them. This was fitting because it was a natural environment that refused to be ignored. Located on the arid High Plains of Southeastern Colorado, the region was hot and dusty in the summer and subjected to freezing temperatures and snowstorms in the winter.

Dust filters into nearly every memory of life in the camps, but it seemed especially mean in Amache. Located on the western edge of the Dust Bowl region, the dust storms in Southeastern Colorado had, just a decade earlier, been powerful enough to suffocate, to blind, and to cause a menacing scourge known as dust pneumonia. Japanese American incarcerees arrived just a few years into soil conservation efforts that aimed to anchor the soil, but the slightest gust of wind could provoke unpleasant reminders that the environmental catastrophe was not yet completely over.

“When the wind blows we have a sand storm. It’s really bad. The sand sifts in from all over and if we’re caught outside in it we’re nearly blinded by the flying sand,” incarceree Henry Fujita wrote in an October 1942 letter.

Despite the challenging environmental conditions, the incarcerees transformed tired beet and melon fields that surrounded the camp into a high yield agricultural enterprise. In 1943 alone, they produced some 4 million pounds of vegetables, generating enough surplus that they were able to send produce to the other WRA camps as well as to the US Army.

Incarcerees also transplanted fast-growing Siberian elm saplings from the Arkansas riverbed and planted them in neat rows alongside the barracks in order to serve as wind breaks and to provide some shade during the sweltering summers. Many of these trees are still standing at the site today and, along with some remaining barrack foundations, form a partial blueprint of the prison city that briefly existed there.

The town of Granada, Colorado and Amache were less than a mile apart and they became interdependent on one another in many ways. Incarcerees were permitted to pass into town to make purchases, resulting in an economic boon to the depressed region. But the relationship, as former incarceree Thomas Shigekuni put it, was “strained to say the least.” Amache’s new high school and false rumors of rich foods and a luxurious lifestyle behind the barbed wire, fueled the misguided idea that Japanese Americans were being coddled by the US Government.

Amache was the only camp with its own silk screen shop and, over the course of its two-year run, it produced over 250,000 navy posters and countless prints, pamphlets, and other ephemera for the Japanese Americans confined in the camp. The pervasive dust presented a problem here too. The poorly constructed barracks offered little protection from the elements — for workers or wet posters — so the shop would have to shut down entirely during the frequent sandstorms.

As their indefinite detention wore on, incarcerees did their best to occupy their time and bring a sense of normalcy to their daily lives at Amache. They played sports and went to school, organized clubs and outings, and found ways to make art and beautify their environment, among many other things. But the barbed wire and guard towers that surrounded the camp served as stark reminders of their imprisonment.

Ochikubo didn’t shy away from showing these uglier parts of camp life. Although the guard tower is unoccupied in the photo below, many former incarcerees recalled the stark psychological impact that the occupied towers — and the watchful eyes of armed guards — had on them.

Despite the injustice of being wrongfully detained by their own government, Amache had the highest rate of volunteerism among the 10 WRA camps, with nearly 1,000 men and women serving in the war effort. Thirty-one of those servicemen and women were killed in action, and the image below captures one of the dust-blown funerals that ensued.

A single self portrait of George Ochikubo is the only documentation we have of the man behind the camera. If anyone has more information about him, please reach out to info@densho.org.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director

Make a gift to Densho to support the Catalyst!

[Header: An approaching sandstorm over Amache. Courtesy of the George Ochikubo Collection.]