August 26, 2020

It is one of the most poignant—and often told—stories of the WWII roundup and incarceration of Japanese Americans: the wrenching decision that had to be made about a beloved pet as families were being forced to leave their homes in the spring of 1942. Unable to take the pet with them, the family has to leave it behind in the care of friends, neighbors, or strangers. In most cases, the family never sees the pet again.

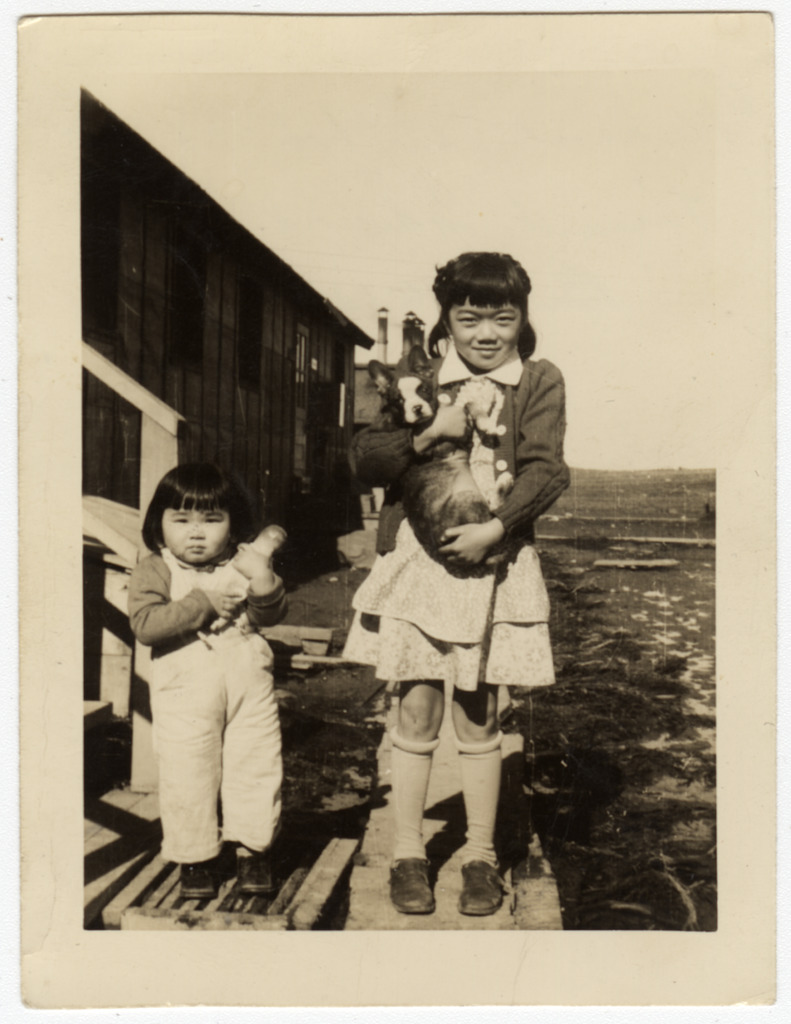

You come across many stories in this vein in oral histories and in literature about the incarceration, and such stories have seemingly come to proliferate. One origin story is found in an often reshared pair of photographs (which can be found in Densho’s collection) of the Moji family of Bainbridge Island and their dog King. The devoted King had to be left behind with neighbors when his owners were taken from Bainbridge, but he reportedly refused to eat and subsequently starved to death.

Yoshiko Uchida’s pioneering 1971 children’s book, Journey to Topaz, includes the story of the family dog that has to be left behind and that dies shortly thereafter. (It turns out this story was based on the Uchida family’s real life dog, as related in her memoirs Desert Exile and The Invisible Thread.) And there is a powerful scene of a woman killing the family dog before being sent off to camp in Julie Otsuka’s widely-read 2002 novel When the Emperor Was Divine.

More recently, pets-left-behind stories have become a common element in children’s literature on the incarceration. It is a central plot element in the recent children’s novels Dash by Kirby Lawson (2014) and Paper Wishes by Lois Sepahban (2016), and the children’s picture book My Dog Teny by Yoshito Wayne Osaki—and a less critical element in many other books such as The Journal of Ben Uchida: Citizen 13559, Mirror Lake Internment Camp (1999) by Barry Denenberg and A Diamond in the Desert (2012) by Kathryn Fitzmaurice. Gary T. Ono also wrote about pets and the incarceration for Discover Nikkei in 2012.

Though often effective in conveying the harshness of the forced removal, these stories of pets left behind have led many to believe that all pets suffered such a fate and have obscured the stories of pets in the concentration camps. It turns out there are many interesting—and no less poignant—stories of this kind.

Getting Pets Into Camp

Though not necessarily large in number, many inmates recall stories of pets in the various types of concentration camps that held Japanese Americans. In some of the camps, pets and the policies towards them became sources of discord between inmates. The exclusion orders that forced Nikkei from their homes expressly banned them from taking pets along, but pets nonetheless found their way into the camps. Most pets entered the camps in one of two ways: they were found at the camp sites and adopted, or they were later shipped by friends to the concentration camps.

Those pets that were adopted on site fell into two categories. Many inmates made pets out of the local fauna. For instance, Minidoka Reports Officer John Bigelow noted that many inmates there trapped jackrabbits they made into pets, and others kept lambs, chickens, geese, and pigeons.[1] At Topaz, the community council noted prairie dogs, coyotes and “even a badger” (!) that were kept as pets.[2] Various types of reptiles[3] were also popular pets, as well as some birds. At Heart Mountain, Shig Yabu adopted a magpie he named “Maggie,” and later wrote a children’s book about her.[4] Other inmates adopted domesticated animals such as dogs and cats that somehow found their way into the camps, presumably from nearby small towns. At Gila River, Reports Officer Ethel A. Flemming wrote that “a good many Indian dogs have drifted in and stayed in and around camp,” potentially another source of inmate pets.[5]

There are also numerous stories of prewar pets that were later sent by friends. Mas Hashimoto recalled that his family had given “Sunny,” the family dog, to a friend in Watsonville, but the friend reported that “our dog was not eating well, and so she wrote to us. When we got to Poston, Arizona, she asked if the dog could be sent to us because she didn’t want the dog to die under her care. So she sent the dog to us by Greyhound bus….” Joyce Okazaki remembered that her next door neighbor brought their dog to rejoin the family at Manzanar, while May Y. Namba recalled their family dog being shipped to Minidoka.

And despite the prohibition of conveying pets to the WRA camps, at least a few did come with the inmates. Charles Kikuchi’s family somehow acquired a puppy that had been born at Tanforan and were able to find a sympathetic staffer who allowed them to take the dog with them to Gila River.[6] Isao Kikuchi (no apparent relation) was one of the early “volunteers” at Manzanar who helped to finish building the camp. Among those who drove his own car there, he was able to bring his dog along.

Pet Politics in the Camps

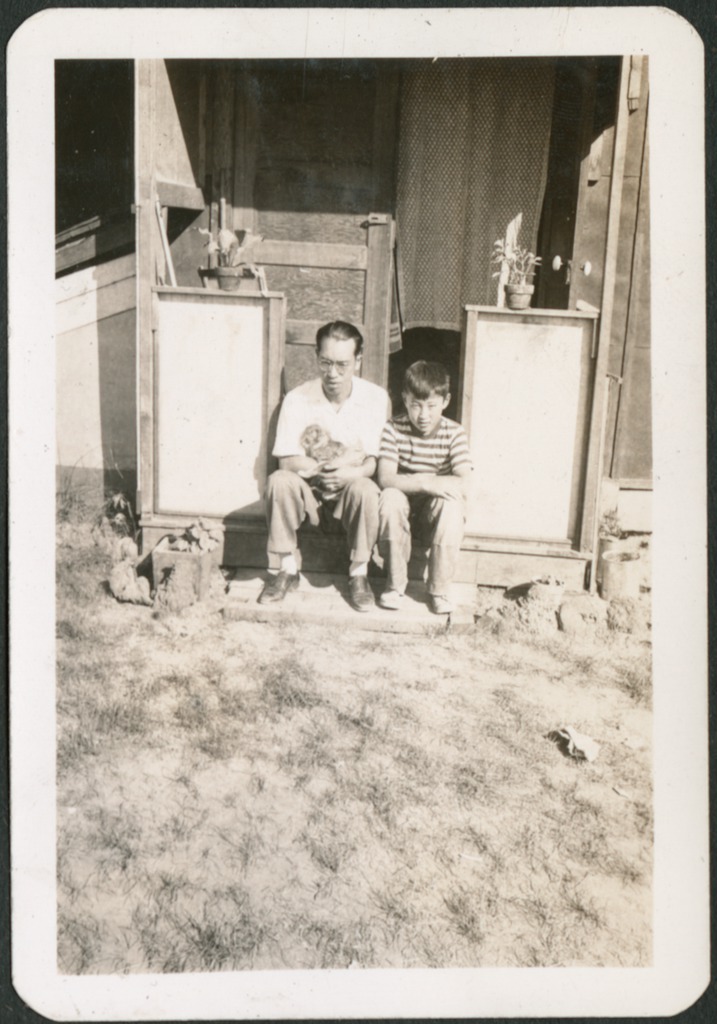

Once in the camp, pets drew much attention beyond their immediate families, given their relatively small numbers. Hashimoto called Sunny “the petting zoo,” noting that “she was such a nice dog she would go to anybody and everybody.” Charles Kikuchi’s family dog—named “Blackie”—became a neighborhood pet. “Everyone comes over to pet it,” he wrote in his diary. “I guess they haven’t seen a dog a long time.”[7] When Maggie, the magpie, learned to talk, “word starts spreading all throughout camp.” Yabu recalled that the bird “served the Heart Mountain internees by entertaining, being one of the internees.”

While the WRA did allow pets, they were technically not allowed at the “assembly centers” or in the enemy alien internment camps. But there were at least a few pets in these camps as well. Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study fieldworker Tamie Tsuchiyama wrote about Santa Anita that “[s]ince coming to camp I have noticed only two cats, one of which recently gave birth to several kittens.”[8] Charles Kikuchi wrote that at Tanforan, “[t]here are five kittens living under our barracks and the people are taking them for pets.”[9] In his internment memoir, journalist Yasutaro Soga wrote that the Santa Fe internment camp “was full of cats,” adding that while pets were forbidden, “this rule was overlooked if they were kept outdoors. Men like Mr. Yamada made pets of the stray cats, treating them like their own children.”[10]

Inevitably, in the crowded and politically charged environment of a concentration camp, pets also sometimes became points of contention. June T. Watanabe, in her capacity as secretary to a block manager at Rohwer, noted a case of a pet cat that some in the block objected to. The cat was later found dead in the forest. “I don’t see how it got out, somebody must have gotten in there out of spite, taken that cat, take it out there and died, killed or something….,” she recalled. Blackie first divided the Kikuchi family, then the block. At block meetings, neighbors complained about Blackie, citing the disturbances brought about by her many male suitors and fears that she might carry disease. As a result, resentment grew against the family among others in the block, furthering their mother’s opposition to Blackie.[11]

“Blackie is having another romance. There are about three dogs living in the next block and they all come over to court Blackie. She is very conscious of male dogs now. Yesterday, she and one of her friends had a wrestle on the lawn by the mess hall and she managed to tear all sorts of holes in the new lawn. The cooks were quite angry about the whole thing, but they have not said anything about it.”

Charles Kikuchi diary, Dec. 2, 1942

As similar disputes grew at other camps, camp administrations and inmate community councils debated policies for how best to handle pets. At Topaz, the community council formed a “Dog Committee,” which worked with the project attorney to address complaints about dogs and also the concerns of the dog owners.[12] The group worked through the summer of 1943, coming up with a pet ordinance that went into effect in September. As of September 3, only dogs, cats, and canaries could be kept as pets; all dogs had to be registered and given rabies shots; dogs were banned from dining halls; the washing of dogs in laundry tubs was banned; and dog owners would be liable for any damages or injuries caused by their dogs. Dog owners protested both the laundry tub ban and the inoculation decree, with the council eventually agreeing to make the inoculation voluntary unless there was a rabies outbreak. When such an outbreak did occur in Utah in the spring of 1944, mass inoculation was decreed for the 102 licensed dogs at Topaz, but some owners still resisted. Similar policies evolved at other camps.[13]

“I don’t know what happened to them after we left”

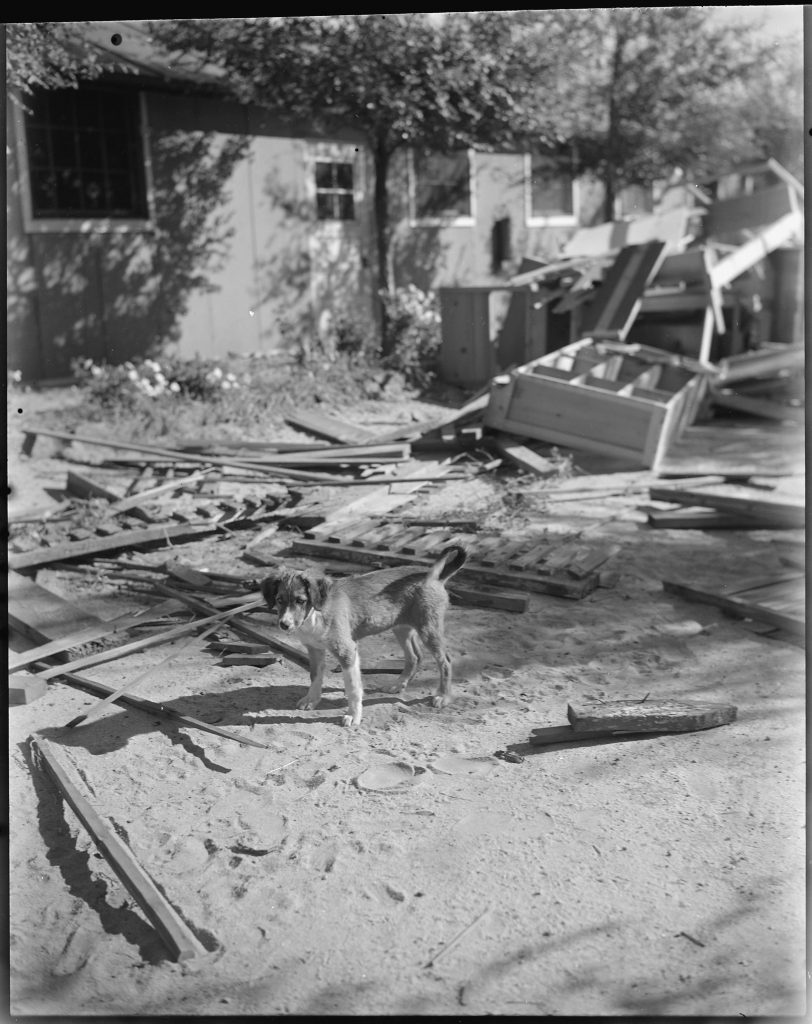

As the camps began to shut down in 1945, questions about the fate of the camp pets emerged. At the end of 1944, the WRA agreed to a policy whereby they would ship “dogs, canaries and even cats if they are bona fide family pets of the evacuees,” but not “such ferae naturae as snakes, wild birds, badgers, etc., that have often been acquired at the centers.”[14] But with many inmates facing seemingly overwhelming concerns about housing, employment, and other aspects of post-camp life, scenes similar to those that took place during the forced removal regarding the fate of pets undoubtedly recurred.

Among the last to leave Topaz, Midori Suzuki recalled her mother feeding the many abandoned dogs. “So I don’t know what happened to them after we left; hopefully they picked them up and took them somewhere,” she noted. Heart Mountain Community Analyst Asael T. Hansen wrote that the “atmosphere of desertion and desolation was made more marked by lonesome, hungry cats crawling over the trash heaps,” after the last inmates left in November 1945.[15] In a heartbreaking passage from her November 1945 report,[16] Flemming, the Gila River reports officer, wrote:

“It has been necessary for Internal Security to kill over three hundred dogs and cats which made a hunger march on the staff quarters after the evacuees had left. The situation and condition of these animals, whose only crime was the ancestry of their owners, has been pitiful as well as creating a problem.”

Ultimately, the story of pets in the concentration camps is one that illustrates how Japanese Americans sought agency over their lived experience while incarcerated, sometimes in contravention of official policy. It is one of many largely untold stories of that experience that helps to expand our knowledge beyond the archetypal stories of dogs having to be left behind when their owners were incarcerated. And there is undoubtedly much more to be uncovered.

—

By Densho Content Director Brian Niiya

[Header photo: Warren Suzuki (right) and Jack Hamada (left) holding a dog in front of barracks at Minidoka concentration camp, Idaho. Courtesy of the Suzuki Family Collection.]

References

1. John Bigelow, Minidoka Report No. 58, Apr. 10, 1943. Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (JAERR), The Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley. BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder P3.95:3.

2. Topaz Community Council Meeting minutes, March 29, 1943. JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H1.49:5.

3. Karl Lillquist, “Imprisoned in the Desert: The Geography of World War II-Era, Japanese American Relocation Centers in the Western United States” (Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, September 2007), 488.

4. Shigeru Yabu, Hello Maggie! Illustrated by Willie Ito. Camarillo, Calif.: Yabitoon Books, 2007.

5. Ethel A. Flemming, Weekly Report [Gila River], Sept. 24–30, 1945. JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder K1.10:4.

6-7. Charles Kikuchi diary, Oct. 8, 1942, p. 856. JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.80:06**

8. Tamie Tsuchiyama, “A Preliminary Report on Japanese Evacuees at Santa Anita Assembly Center,” July 31, 1942, p. 2n1. JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B8.05.

9. Charles Kikuchi diary, Aug. 19, 1942, p. 570. JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.80:04**

10. Yasutaro [Keiho] Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai’i Issei (Translated by Kihei Hirai; Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), 138.

11. Charles Kikuchi diary, Nov. 5, 1942, p. 1094, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.80:08**; Charles Kikuchi diary, Apr. 4, 1943, p. 2466, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.80:15**; Charles Kikuchi diary, Apr. 16, 1944, p. 4785, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.80:27**

12. Topaz Community Council meeting minutes, July 5, 8, and 12, Aug. 23 and 26, and Sept. 2 and 6, 1943, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H1.49:6; Topaz Times, Aug. 31, 1943, 2; Topaz Community Council meeting minutes, Mar. 23, 1944, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H1.49:8; Topaz Community Council meeting minutes, Apr. 3, 6, 14, May 4, and June 1 and 5, 1944, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H1.49:9

13. See, for instance, Russell A. Bankson, Summary of Monthly Narrative Reports, Topaz for Month Ending March 1944, p. 4, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H1.76; George Nakaki, [Heart Mountain] Community Government, Evacuee Viewpoint Final Report + appendices, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M1.05:8; Richard Nishimoto diary [Poston], June 27, 1944, JAERDA BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder J6.13 (11/15).

14. Edwin Ferguson [WRA solicitor] to Frank Barrett [Topaz project attorney], Oct. 14, 1944, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H1.64:2.

15. Asael T. Hansen, “My Two Years at Heart Mountain: The Difficult Role of an Applied Anthropologist,” in Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress, edited by Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, and Harry H. L. Kitano (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1986; Revised edition, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991), 37.

16. Ethel A. Flemming, Weekly Report [Gila River], Nov. 12–18, 1945, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder K1.10:4.