March 22, 2019

Patsy Takemoto Mink was born in Pā`ia, Maui, on December 6, 1927, to Nisei parents Suematsu and Mitama Takemoto. Like many Japanese Americans growing up in Hawai`i at that time, she was raised on a sugar plantation. However, as the Sansei daughter of a land surveyor allotted a private cottage, company car, and two acres of land, her experiences were very different from her mostly Nisei peers in the overcrowded and heavily segregated plantation camps—differences she began to see clearly once she started attending school. As a young girl, she would accompany her father to local election rallies, sparking an early interest in politics.

Patsy was a sophomore at Maui High School when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into WWII. Over 1,000 Buddhist priests, Japanese language school instructors, newspaper editors, and other community leaders were arrested throughout the islands and imprisoned, but the Japanese population in Hawai`i was ultimately spared the mass incarceration enacted on the mainland. Patsy’s own father was swept up in the arrests, but was later released. Against this backdrop of fear and mistrust, Patsy decided to run for student body president in her senior year. Her campaign was successful, and she graduated in 1944 as both student body president and class valedictorian.

After high school, she enrolled at the University of Hawai`i as a pre-med student—having decided at age four that she wanted to become a doctor. She wound up transferring to the mainland at the end of her sophomore year, first to Wilson College in Pennsylvania, and then to the University of Nebraska. At Nebraska, Patsy was assigned to the International House, a separate dormitory for foreign students as well as American students of color who were barred from the school’s dormitories, fraternities, and sororities. Outraged at the blatant segregation, Patsy began giving speeches and writing letters to protest the university’s discriminatory housing policy, and mobilizing other students to participate as well. She was soon elected president of the Unaffiliated Students of the University of Nebraska—a separate branch of student government for the “international” students excluded from the school’s regular dorms and Greek system—and the board of regents ended the policy of segregation that same year.

Just when she was beginning to thrive, a serious thyroid condition forced Patsy to leave Nebraska and return to Hawai`i for surgery. She finished college at the University of Hawai`i, and applied to more than a dozen medical schools in the spring of 1948—when just two to three percent of students admitted to medical schools were women. She was rejected by them all. After a few months working as a clerk on a local Air Force base, she decided to apply for law school instead and was accepted to the University of Chicago.

While at Chicago, Patsy met geology student John Francis Mink, and they married in 1951, a few months before they both graduated with their respective degrees. John immediately found a job, but Patsy’s search was less fruitful, and she ended up back at her student job at the University of Chicago Law School library. They moved back to Hawai`i soon after their daughter Gwendolyn was born, in 1952, where Patsy, again, encountered steep obstacles in finding a job that matched her qualifications while John, again, was hired almost immediately. Patsy was considered a resident of John’s home state of Pennsylvania under a law that required women to take the residency status of their husbands, making her ineligible to take the Hawai`i bar exam. Undeterred, she challenged the statute and got the attorney general to reverse the denial.

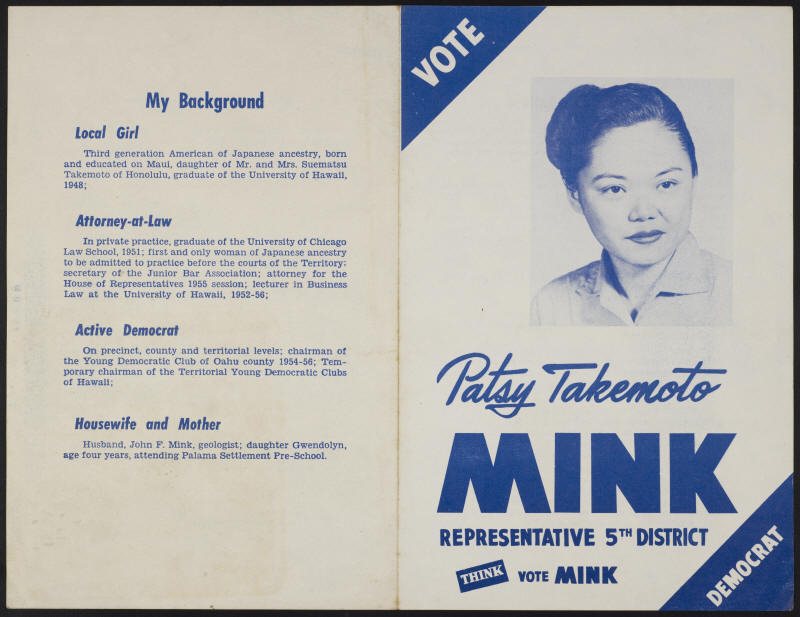

Even after passing the bar in 1953—becoming the first Japanese American woman to practice law in Hawai`i—she was not well accepted within the legal profession. Law firms she applied to would reject her outright because of her interracial marriage, because she had a child, or because they believed a woman “should not be out late at night.” Tired of being excluded, Patsy started a solo practice, taking on criminal cases, divorce, adoption, and other cases that more established (and male-led) law firms would typically turn down. But with few clients willing to hire a young Asian American woman as their attorney, Patsy found herself with extra time on her hands. She began to volunteer for the Democratic party in Honolulu, working to engage younger voters and helping to usher in the “Revolution of 1954” as chairman of the territory-wide Young Democrats club.

In 1956, Patsy decided to run for the territorial House of Representatives—bucking the Democratic party leadership, who didn’t believe a Japanese American woman was “electable” and advised her not to run. “I had no visible support in the community, no organizational support,” she later said—but that didn’t stop her. Patsy walked her full district, more than half the land area of Oahu, and went door-to-door to speak directly with voters. The grassroots strategy paid off, and she became the first Japanese American woman elected to the Hawai`i legislature. She achieved another first just two years later, when she won a seat in the territorial Senate (once again, without the support of the party’s male leadership).

When Hawai`i became a U.S. state in 1959, Patsy filed early and unopposed for the House seat. She almost became the first Japanese American of any gender elected to Congress—until Daniel Inouye gave in to party pressure to withdraw from his Senate run and re-file as a candidate for the House, just a few days before the filing deadline. Unable to compete with his official stamp of approval from the party establishment, and his record as a war hero, Patsy lost the election.

But after a few years back at her law practice, Patsy’s time finally came. She ran a successful campaign for the Hawai`i Senate in 1962, and another one for the U.S. House of Representatives just two years later. She was sworn in on January 4, 1965, becoming the first woman of color elected to Congress, and served six consecutive terms from 1965-1977.

During her time in Congress, Patsy was a staunch advocate of education, the environment, open government, and equal opportunity for women and people of color. She’s best remembered for authoring the revolutionary Title IX Educational Amendment of 1972, which mandated that any institution receiving federal funding equally support men and women in academics and athletics, and its follow-up Women’s Educational Equity Act in 1974. But some of her lesser known accomplishments include introducing the country’s first comprehensive early childhood education act (passed by both houses of Congress but vetoed by Nixon in 1971); sponsoring legislation creating bilingual education, student loans, special education, and Head Start; attempting to block funding for the Vietnam War and co-sponsoring a (ultimately unsuccessful) bill to immediately cease military activity in Vietnam; bringing a Supreme Court case against the Environmental Protection Agency over its refusal to disclose “sensitive” information on nuclear testing in the Aleutian Islands; and helping to block the confirmation of notorious racist and misogynist G. Harrold Carswell to the Supreme Court in 1970, paving the way for Justice Harry Blackmun, who would write the majority opinion in Roe v. Wade three years later. She even ran a brief presidential campaign from 1971-1972.

After twelve years in the House, Patsy made a run for the Senate, but lost to Representative Spark Matsunaga. She served two years as Assistant Secretary of State for Ocean and International, Environmental, and Scientific Affairs, and another three years as the first woman president of Americans for Democratic Action, before returning to Hawai`i in 1980.

Soon after arriving back in Hawai`i, Patsy got wind of Honolulu County’s controversial plans to construct a power plant without public input and became the pro bono attorney for the Waipahu community group opposing the project. With Patsy’s legal support, the group successfully blocked construction of the plant. Although she had initially planned to retire from politics, the campaign drummed up support for her to return to the campaign trail, and in 1982 Patsy was elected to the Honolulu City Council.

Despite an unsuccessful mayoral campaign in 1988, Patsy later returned to Congress in 1990, to serve out Rep. Daniel Akaka’s seat when he was appointed to fill the Senate vacancy following the death of Spark Matsunaga. Campaigning on the slogan, “The Experience of a Lifetime,” she shot down sexist criticism that she was “past her prime” and won both the special and regular elections. She remained in Congress as a strong liberal voice for Hawai`i and the nation over the next twelve years, and continued to fight for gender and racial equity, the protection of social welfare programs, and government oversight.

Patsy died in Honolulu on September 28, 2002, at the age of seventy-four. She was survived by her husband, her daughter, and thousands of public citizens whom she had served during her long and distinguished career. As a show of just how well-loved she was by her constituents, her name remained on the November 2002 ballot and she was posthumously re-elected by a landslide.

Despite facing constant criticism and outright discrimination because of her identity as a Japanese American woman, Patsy Mink never hesitated to speak her mind and stand up for what’s right, even if it meant stepping on a few toes. “It is easy enough to vote right and be consistently with the majority,” she famously said. “But it is more often more important to be ahead of the majority, and this means being willing to cut the first furrow in the ground and stand alone for a while if necessary.”

Patsy Mink may have been the first of many things, but thanks to her leadership, she won’t be the last.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator

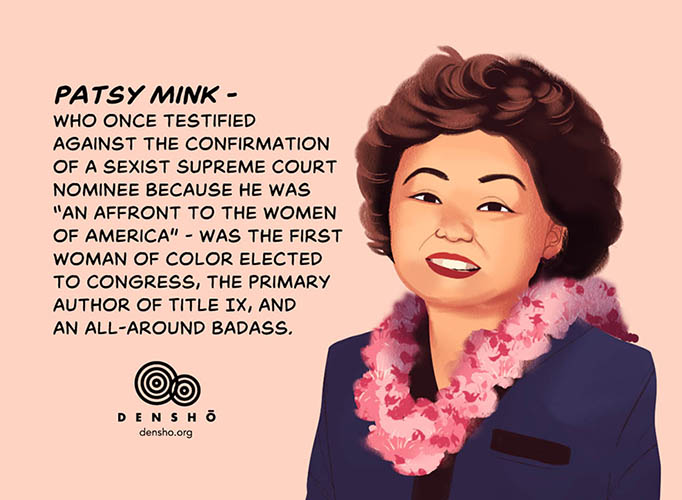

Header image: original artwork by Kiku Hughes. Kiku is a comics artist living and working in the Seattle area. Her work has been featured in “Beyond: A Queer Sci-Fi and Fantasy Comic Anthology”, “Elements: Comic Anthology by Creators of Color” and Short Box Comics Collection. She is currently working with First Second Books to publish her first graphic novel, about Japanese American incarceration. Funding for Kiku’s work was generously provided by a grant from the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture.

For more information, see Patsy’s biography in the House of Representatives Archives, and Tania Cruz and Eric K. Yamamoto’s “A Tribute to Patsy Takemoto Mink.”