November 1, 2021

Award-winning mystery novelist, public historian, and journalist Naomi Hirahara’s new novel, Clark and Division, follows the story of a young woman searching for the truth about her revered older sister’s death, and the struggles of one Japanese American family released from mass incarceration at Manzanar. Hirahara recently joined Brian Niiya, a longtime friend and Densho’s Content Director, to talk about the novel, her literary icons, the secret lives of Nisei in resettlement Chicago, and more.

Below is an excerpt of Naomi and Brian’s discussion from “Mystery After Manzanar,” which has been edited for length and clarity. The full conversation is available to view here.

Brian Niiya: Could you give us a summary of the book?

Naomi Hirahara: Sure. Clark and Division is a book about sisters, and it’s also specifically about a Japanese American family. The Ito family, who are from an area called Tropico, which, if you know Los Angeles, it’s kind of around the Atwater area, close to Los Angeles and Glendale. And so the father, Gitaro Ito, works as a manager for the produce market and during World War II they’re forcibly removed from their homes and they are sent to Manzanar. And from there, there’s early release so the older sister — this book is told from the younger sister’s point of view, Aki, and she idolizes her older sister Rose. Rose is the one who does the early release and she goes to Chicago, which was the number one destination for Nisei from the ten mass incarceration camps. And the rest of the Ito family, Aki and her parents, follow some months later only to discover something tragic has happened to Rose. So now it’s up to Aki, who’s always been in the shadow of her older sister, to find out the truth as well as to carry her parents through this tumultuous period of their lives.

BN: Now, this is a little bit of a departure for you in the sense that you haven’t really written other purely historical novels, even though your Mas Arai books have a lot of flashback scenes and stuff. Where did the seed for this one come from?

NH: I think I was kind of avoiding straight historical fiction and one reason why is I love the contemporary voice. I love writing about, like, spam musubi or the weird way Niseis dried their persimmons on the clothesline. Just those everyday kind of observations, I adore, so I try to integrate in the Mas Arai mysteries. I think in some ways I was, not necessarily waiting, but I just thought the appropriate time for me to write fiction — especially about the Nisei generation — is the time where that generation would be no longer. I know there’s some Nisei that are still alive today, but their memories may be compromised, and I have really noticed that when I interview someone in their 50s, 60s, 70s, that’s really different than when I’m talking to them in their 90s. So I think maybe emotionally or psychologically I felt like, “Okay, Naomi, this is your freedom to kind of explore this in fiction.”

Brian, you probably are more comfortable with the Nisei female voice than I am because Nisei women love you. [Laughs] You’re a spoiled Sansei boy, whereas I think the relationship between a Nisei woman and a Sansei woman, it’s a little more complicated. I didn’t really experience this firsthand because my mother’s Issei, so I’m kind of a Nisei raised by a Japanese immigrant woman. I think that gave me some insights to my character Aki. The book is written in first person, but I’ve been trying to crack the Nisei female voice for some time in fiction. I noticed there was this level of optimism, yet I know there was so much trauma that occurred, so how do I poke this veneer?

I had written a noir short story called “The Chirashi Covenant,” and it was set in 1950s. They were all beauty queens. I wanted to write about more attractive people because I’m very drawn to unattractive people. [Laughs] So they were former, like, Nisei Week type queens in 1941, and this is 10 years later. And there’s a kind of a femme fatale who has an affair with a white guy. She’s married with children and she eventually chops that white guy up and puts him into a suitcase and drops him into the ocean. Some people who really like dark noir, outside of the community, liked it, but I think everyone else — I don’t think most people read it, but the ones who did were probably puzzled and not really thinking, “That is my aunt or mother.” It wasn’t representative. So it was like, well, how I tend to write mysteries, how do I write this kind of character? And it wasn’t until I was working on Life after Manzanar and reading about the criminal activities that had taken place by young people in Chicago and without parental supervision, and that’s when it really occurred to me, like, this is it, this is how I could write the Nisei. The character has optimism, has filial piety and all these things, but the outside forces are very dark, so how is she going to interact with that?

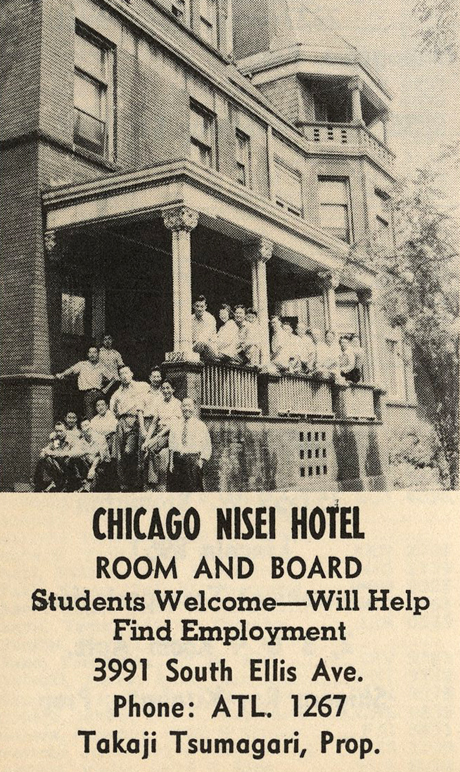

BN: I think the novel really captures that sense of being a Nisei at that point in time. This mixture of just terrible living conditions that may or may not be better than camp. There are jobs, but they’re all kind of menial. And of course then you’ve got this family tragedy on your hands, and at the same time, you’re right, the sense of optimism, excitement, just freedom for so many of the Nisei. It captures that resettlement period really, really well. Was there any doubt you’re going to write about Chicago or did you consider, like, New York, Denver, other major resettlement hubs as well?

NH: I was thinking about Bronzeville, but then I wasn’t really getting this throughline that the Nisei had been exposed to a lot of crime. I mean, I am a mystery writer so I am looking for kind of dark things. And there were families that were returning together and it was a slightly different time, so I think that was the difference. Chicago is just such a notorious place. Just the mob and how ethnically it’s so interesting, like the Polish community, the Irish community. That whole city, it’s so different than Los Angeles.

I found a document with the Chicago Resettlers Committee from 1946, where it had this list of people having babies out of wedlock, and then abortions, which were illegal at the time, and several other very specific crimes. I just read that and I said this is crazy. I knew, through the Children’s Village [in Manzanar], there were babies, interracial babies born out of wedlock. I was cognizant of that, but the other types of crimes, I was kind of shocked and surprised. And then I went back to the same oral histories, but I was reading around the edges. They would say, “Oh yeah, there was a little skirmish. There was a little fight.” It wasn’t the center of the oral history, but once I became more aware that there were very specific criminal problems and then when I look back, it’s like, oh, people are referencing it but not very directly. Us being Japanese American observers, we’re very used to it, reading between the lines. So that’s why I knew it had to be Chicago.

BN: I was also wondering, were you influenced at all by other works on this period? I think we both are admirers of Pineapple White, John Shirota’s novel set in LA in the late 40s. But were there other works like that that were significant for you?

NH: I’m a big fan of Hisaye [Yamamoto]. She’s written some post-camp stories which are just devastating. I mean, she’s just such a queen. I feel lucky that I knew Hisaye. It’s not like we were best buddies or anything, but she was on my rolodex and we would get her hand typed material when I was [at the Rafu Shimpo].

BN: There’s a couple of unanthologized pieces she did in the Rafu in the early 60s that were, it was a period when supposedly Nisei weren’t talking about camp, but she did. Even called them concentration camps. Like this 1960 story [“Pleasure of Plain Rice”] about leaving camp as a student and then coming back to camp after a brother dies in the 442nd, so I think some of these should really — there needs to be another anthology of her work beyond Seventeen Syllables because there’s a lot more there in those old Rafus.

NH: She was a role model to me in the sense just of her presence. Just physically, she was a small person that I think was underestimated. I saw it for myself where people didn’t realize who she was and didn’t let her into a talk, like, “Oh, we’re all full.” And I’m saying, “You don’t know who this is!” She was very unassuming, but she was a journalist too, for the African American paper [the Los Angeles Tribune]. She was motivated by social issues in addition to her art, so I related to her from that point of view. I loved her friendship with Wakako Yamauchi and I think that was meaningful to me too. To see friendship among creative people because so much of the time society characterizes female friendship as being adversarial and competitive and it was a good model, like, it doesn’t have to be like that.

BN: Are we going to see Aki again?

NH: We are. I said this would not be a series, it would be standalone, but they wanted to follow demand. So yeah, there’s going to be a follow-up. It’s called Evergreen and it’s set in 1946 Los Angeles, so it turns out I will be covering Bronzeville.

—

Naomi Hirahara is an Edgar Award-winning author of multiple traditional mystery series and noir short stories. Her Mas Arai mysteries, which have been published in Japanese, Korean and French, feature a Los Angeles gardener and Hiroshima survivor who solves crimes. The seventh and final Mas Arai mystery is Hiroshima Boy, which was nominated for an Edgar Award for best paperback original. Her first historical mystery is Clark and Division, which follows a Japanese American family’s move to Chicago in 1944 after being released from a California wartime detention center. Her second Leilani Santiago Hawai‘i mystery, An Eternal Lei, is scheduled to be released in 2022. A former journalist with The Rafu Shimpo newspaper, Naomi has also written numerous non-fiction history books and curated exhibitions. She has also written a middle-grade novel, 1001 Cranes.

Learn more about Clark and Division and purchase a copy here.

[Header image: Nighttime street scene in the Gold Coast neighborhood of Chicago, 1940. Photo by Milton Halberstadt, courtesy of the University of California, Davis, Library, Dept. of Special Collections.]