January 9, 2024

As we celebrate the arrival of 2024, it’s time for our annual roundup of prominent Nisei who would have turned one hundred years old in the year to come. We are exiting the peak years of Nisei births on the continent, as their numbers began to fall with 1924 and continued to fall steadily until the late 1930s, even as the earliest Sansei births began. As with their older siblings, those born in 1924 would have their lives profoundly reshaped by World War II. Many of the people on this list were set to graduate high school before their plans were interrupted by forced removal and incarceration.

Military Stories — from both sides of the Pacific

For men born in 1924—who thus turned eighteen as world war raged in 1942—the question of military service played a central role in their lives. While most of the men on this list served in the military—or consciously decided not to—the wartime experiences of this trio and its long aftermath are what they are remembered for today.

Fred Shiosaki was born and raised in Spokane, Washington, where his parents ran a laundry. Being east of the restricted area, the Shiosakis avoided being sent to a concentration camp. Volunteering for the army as soon as the ban on Nisei enlistment was lifted in 1943, Fred saw combat in Italy and France from June 1944 until the end of the European war in May 1945, taking part in the rescue of the “Lost Battalion.” He was awarded a Bronze Star and Purple Heart for his service. After the war, he worked as a chemist and administrator for the Spokane Air Pollution Control Authority and Washington Water and Power Company, while serving on the Washington State Ecological Commission and Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission. He is one of the main characters in Daniel James Brown’s 2021 best-seller, Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II.

Chronicler and advocate of Nisei veterans William Yoshito “Bill” Thompson grew up in Hilo, Hawai`i, the son of a Nisei mother and Scottish immigrant father. At age nineteen, he joined two older brothers in volunteering for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, serving in the Headquarters Company, Second Battalion’s Antitank Platoon. After a career with the Hawai`i State Department of Land and Natural Resources, he became active with the 442nd Veterans Club, later serving as its first mixed-race president, while also contributing many articles on the veterans to the Hawai`i Herald.

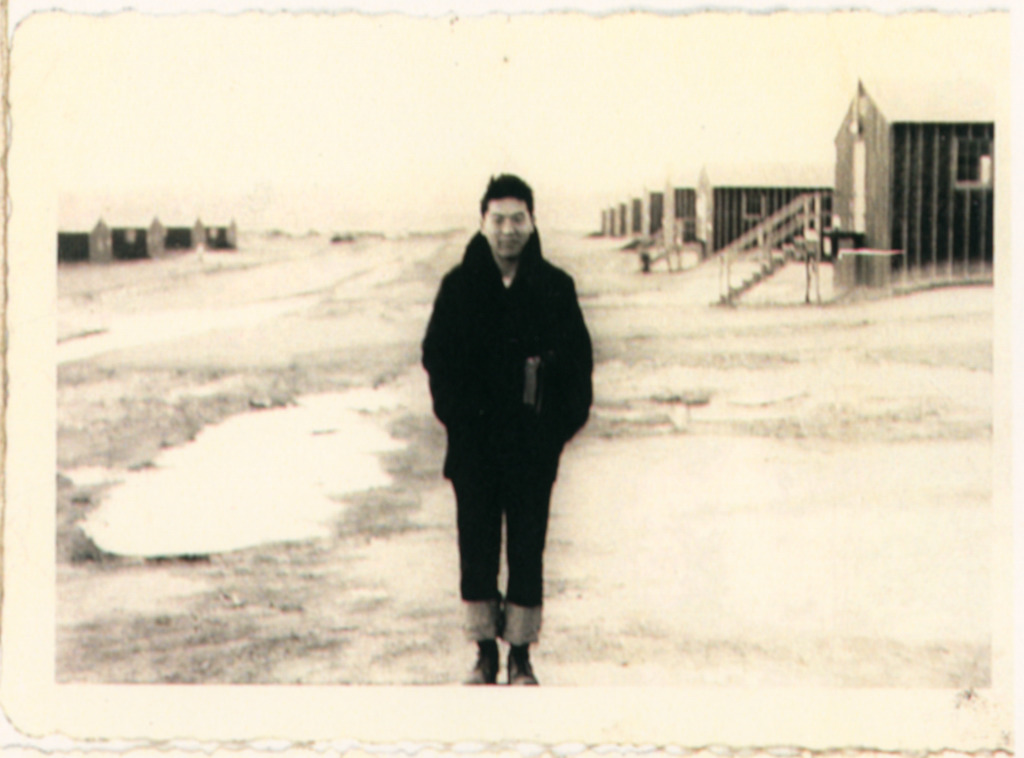

Iwao Peter Sano had a very different kind of military experience. A Nisei born and raised in California’s Imperial Valley, Sano was sent to Japan at age fifteen to be a yōshi—an adopted son of a childless relative—and spent the war years there. As a dual citizen, he was drafted into the Japanese army towards the end of the war and was stationed in Manchuria at war’s end, when he was captured as a POW by the Soviet Union. He would end up imprisoned in Siberia for nearly three years. Released in 1948, he was able to return to the United States in 1952, eventually settling in the San Francisco Bay Area and becoming an architectural draftsman. He chronicled his wartime odyssey in a memoir, 1,000 Days in Siberia: The Odyssey of a Japanese-American POW, published in 1999.

Prominent Players in Post-War Hawai`i

Another group of Nisei veterans played important roles in post-war Hawai`i.

A well-known surgeon in Honolulu, Victor Mori came from a notable Honolulu medical family, then saw his father, grandfather, and stepmother all separately interned during World War II. Victor himself was arrested as a seventeen-year-old and held in solitary confinement for ten days. He later served in the U.S. Army before completing his medical training in the segregated South. He practiced medicine in Honolulu for thirty years, from 1959 to 1989.

Dick Kosaki had a wide-ranging career in academia, politics, and education that touched many lives in postwar Hawai`i. The student body president at McKinley High in Honolulu when the war began, he served in the Military Intelligence Service, becoming an intelligence officer during the occupation of Japan. Returning to the University of Hawai`i after the war, he initially intended to be a lawyer, but ended up pursuing academia instead, finishing master’s and doctoral degrees at the University of Minnesota and returning to teach political science at UH. Getting caught in local politics, he was among a group of professors who met with future Governor John Burns to exchange ideas, and later took on staff positions in both the state house and the U.S. Congress, even as he continued teaching. Returning full-time to UH and entering administration, he was a key figure in the establishment of Hawaii’s community college system, and ultimately served as the acting chancellor of UH Manoa. I had the pleasure of knowing him in his later years, when he was an advisor to the Japanese American National Museum’s International Nikkei Project, as well as serving as interim director of the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai`i.

And then there is Daniel Inouye, the legendary senator and war hero. Rather than rattling off a list of his accomplishments that most of you reading this no doubt are aware of, a couple of observations: While I saw him in many formal settings over the years, where he always showed his stentorian and overly formal voice and demeanor, together with a seriousness of purpose befitting someone in his position, I most remember seeing him in more informal settings back home, especially among his old 442nd buddies, where the pidgin returned and his ribald (and sometimes inappropriate, at least by today’s standards) humor flowed. Was this the same person? And is this duality part of the Nisei experience, especially for those who succeeded in the mainstream world? As younger generations reframe Hawai`i’s history through a settler colonial lens and as views on race and gender shift, I wonder how he and other leaders of his generation will be viewed by history in the years to come?

Artists, Actors, and Writers

For most of us, “artist” or “performing artist” is not the first image we have of Nisei. And yet, as I write these pieces, every year I find a good number of notable Nisei who fall into these categories. No doubt people like me and my friend Greg Robinson, who suggested two of these names, just like to write about them, rather than successful engineers, dentists, or civil servants!

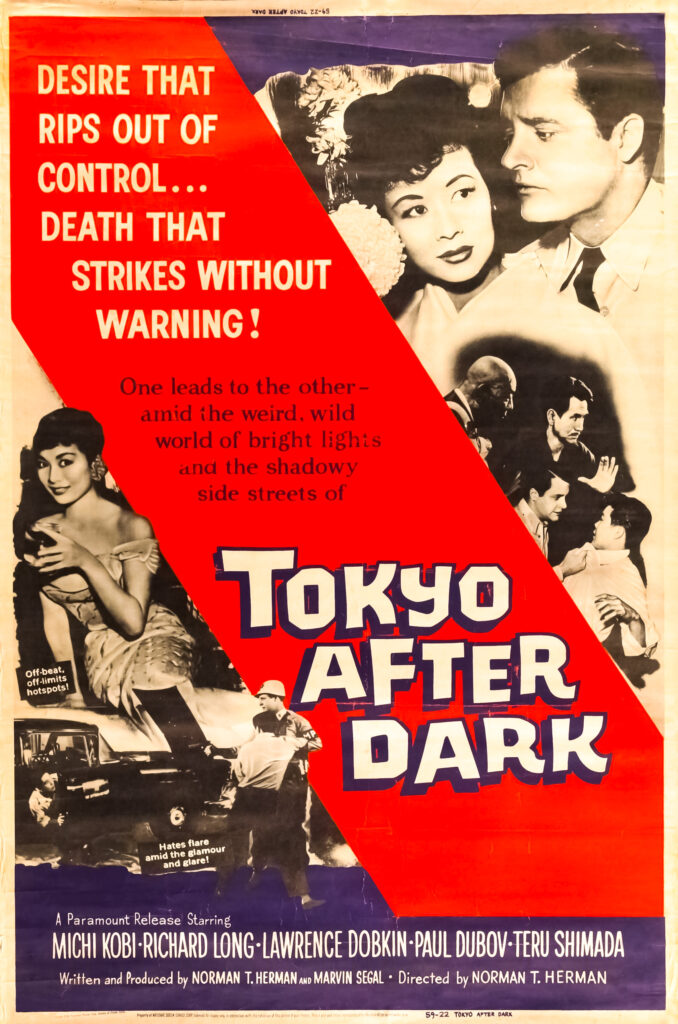

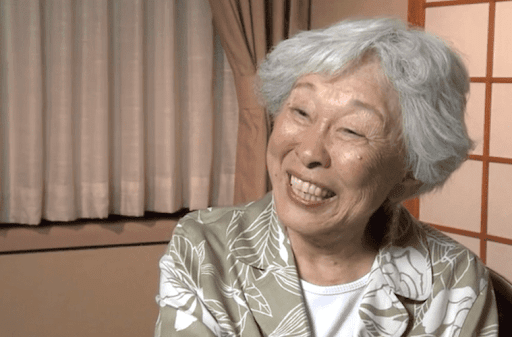

Michi Kobi (Michiko Okamoto) was one of a number of Nisei who pursued acting careers after the war. After a difficult early childhood– her physician father died when she was just a toddler and she spent a subsequent stint in an orphanage–Kobi grew up in San Francisco. She and her mother were forcibly removed to Tanforan and Topaz during World War II. Graduating high school in Topaz, she worked as a nurse’s aide and as a researcher for Community Analyst Oscar Hoffman. While in camp, she found an escape through acting, starring in a school production of Our Town. Leaving for New York at the end of 1944, Kobi was able to secure scholarships to NYU and the New School for Social Research, where she studied drama. Through the 1950s and 1960s, she acted in various stage, television and film productions, starring in Tokyo After Dark (1959), which was produced by a Nisei production company, and playing a supporting role in Hell to Eternity (1960), the first Hollywood film to depict the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans. Kobi spoke frankly about her wartime incarceration in later interviews and was active in the Redress Movement.

Wai`anae born Jerry T. Okimoto was among the group of Nisei artists from Hawai`i who moved to New York in the 1950s in search of greater opportunity and inspiration as an artist. Part of the Metcalf Chateau, a group of seven such artists, Okimoto was perhaps the least well-known back home because he alone never returned to the islands, moving to Long Island after over twenty years in New York City. Known initially for his Pop Art influenced paintings of colorful geometric figures, he turned to sculpture later in his career, specializing in large laminated wood pieces that drew on his experience as a carpenter and house builder in Hawai`i. His works are in the collections of the Whitney and Hirshhorn among other art museums.

Though Wakako Yamauchi was also a painter, she became better known for the striking short stories and plays that often revealed uncomfortable truths behind the “model minority” façade of the Japanese American community. Though her works for the most part were set in the Issei and Nisei eras, there is something that feels quite contemporary about them in their frankness and understanding of gender dynamics and community history. Her work represents a great place to start for someone who wants to understand who we are and how we got here. (Yamauchi’s best-known work is probably “And the Soul Shall Dance,” a short story turned into a play, though I am partial to a short story titled “The Sensei.” These and her first anthology, Songs My Mother Taught Me, are an excellent introduction to her work.)

Community Pillars

While there could be many in this category, I am highlighting three here. Mary Karatsu was best known for her role as a community volunteer for the Japanese American National Museum and Go For Broke, drawing on connections she had made in twenty-eight years as a staff person for the YMCA to lead early fundraising efforts for both organizations while also playing a key on-the-ground role for the former. She also had a fascinating World War II story as a “voluntary evacuee” who spent the war years in New York City, later visiting her family at Heart Mountain and bringing two of her younger siblings back with her.

The next two notables were both the keepers of family and community legacies.

The eldest of legendary Issei photographer Toyo Miyatake‘s four children, Archie Miyatake mostly grew up in Boyle Heights before the war and was a student at Roosevelt High School when the war broke out. Sent with his family to Manzanar, Archie graduated from Manzanar High School and helped his father run the camp photography studio under the auspices of Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises. After the war, Toyo reopened his photo studio, which Archie took over upon the former’s death in 1979. In addition to taking portraits and documenting family milestones, the studio—and Archie in particular—also documented postwar community life as the official photographer for the Rafu Shimpo newspaper for decades. In later life, Archie was active with Nisei Week, serving on the board and as board chairman and was honored as the grand marshal of the Nisei Week parade in 1993. He was also active in efforts to preserve the Manzanar site.

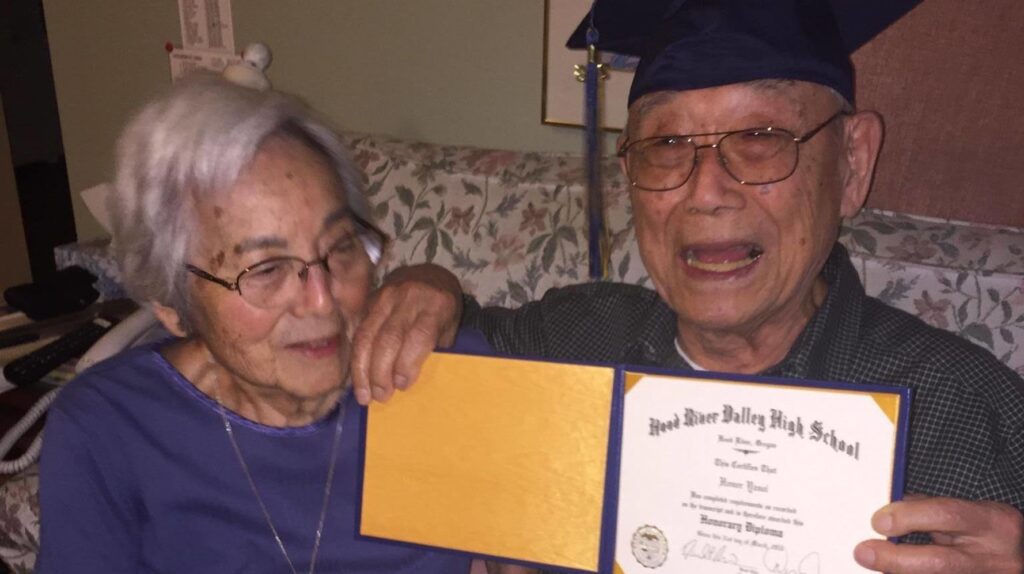

A leader of the Japanese American community in Oregon, Homer Yasui was incarcerated with his family at Pinedale and Tule Lake before leaving the latter in the fall of 1942 to attend college at the University of Denver, going on to medical school as did several other of the Yasui siblings. After a stint in the navy during the Korean War, he settled in Portland, where he was a surgeon, while also being active in the JACL, serving as president of Portland chapter and as a district governor of the Pacific Northwest District Council. In addition to sharing his life story through oral history interviews and countless public appearances, he helped found what is now the Japanese American Museum of Oregon, wrote a series of autobiographical vignettes for his extended family, and tended to an expansive archive related to his family’s incarceration experience, including his brother Minoru Yasui’s widely known legal battle. He was also a key supporter of Densho and remained sharp and engaged well into his nineties until his passing in 2023.

Redress Leaders

Two important leaders of the Redress Movement are among those who would have turned 100 in 2024.

Chiye Tomihiro was a key redress figure in Chicago, serving as the redress chair for the Chicago JACL and the witness chair for the Chicago Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians hearings. Born and raised in Portland, she was sent to the Portland Assembly Center with her family just a month before she was set to graduate from high school. After being transferred to Minidoka, she left in April 1943 to attend the University of Denver, in part because of her family’s friendship with the Yasui family and their presence there. She later transferred to the University of Wisconsin before joining her family in Chicago, where she got involved with the JACL around 1950, during the time they were pushing for naturalization rights for the Issei. An accountant by profession, she remained in Chicago—and active in the JACL—for the rest of her life until her passing at age eighty-seven in 2012.

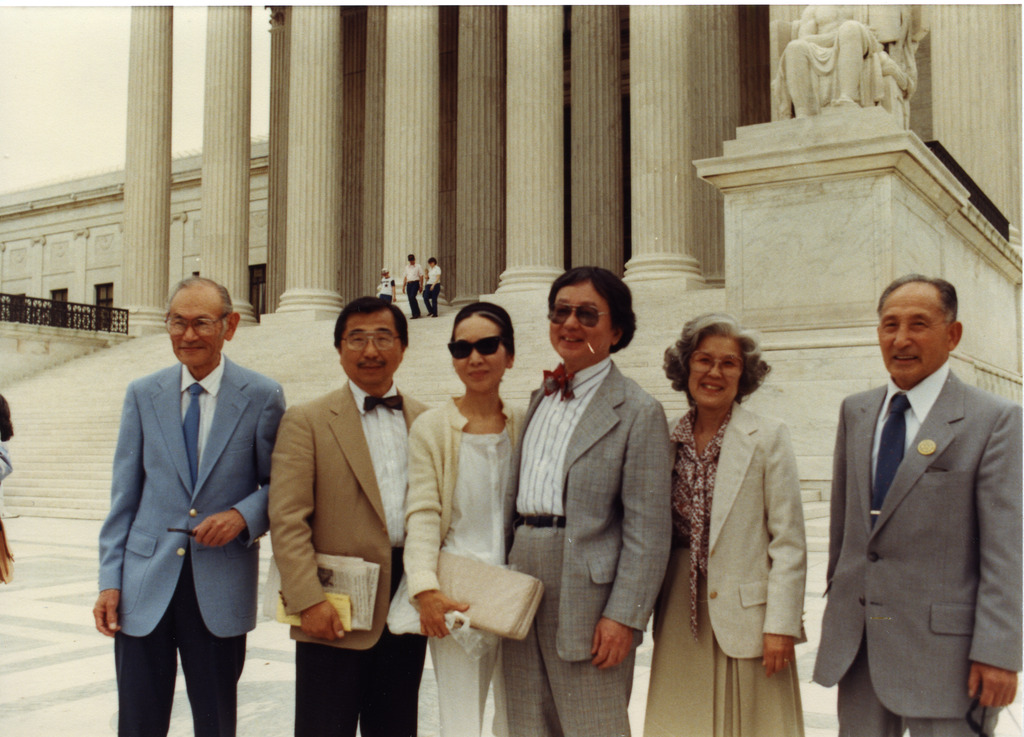

What is there to say about Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga that hasn’t already been said? Her story is the stuff of legend: Applying the skills gleaned from single motherhood and clerical work to activism and research, she became the lead researcher for the CWRIC, where her discovery of key documents fueled the CWRIC’s findings in favor of redress, the outcome of the coram nobis cases of Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui, and the class action lawsuit launched by the National Council for Japanese American Redress. Her papers stowed at UCLA continue to be a valued resource for researchers, most recently for the Irei project.

Resisters

Two prominent resisters are also in the 1924 club. Mits Koshiyama grew up in the Santa Clara Valley working on the family strawberry farm and was in his final year of high school when war transformed his life. Sent to Santa Anita and Heart Mountain with his family, he ended up graduating high school at the latter. Angered by the incarceration, he gave a qualified answer to the “loyalty questionnaire,” and when Nisei eligibility to the draft was restored a year later, he found that the message of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee resonated with him. His subsequent refusal to report for induction led to his imprisonment at McNeil Island Penitentiary. Returning to the Bay Area after the war, he ran a flower nursery and worked as a landscape gardener. When the story of the Nisei draft resisters was rediscovered by activists in the 1980s, Koshiyama became one of the main spokesmen for the resisters, speaking frequently about his experiences until his death in 2009.

After spending five years in Japan as a young child, K. Morgan Yamanaka grew up in San Francisco, the son of domestic workers, and was attending Lowell High School when the war began. Part of the first group from San Francisco to be forcibly removed, he and his family were sent to Santa Anita before rejoining other Bay Area folks at Topaz. Influenced by his resentment at the treatment meted out to Japanese Americans as well as his own family situation—he had both a brother and a sister in Japan—he and another brother both decided to answer “no-no” on the “loyalty questionnaire,” and the whole family ended up at Tule Lake. In the fall of 1943, he and his brother were both fingered as troublemakers by the administration and were imprisoned in the infamous stockade. After his release, he was among the Nisei who renounced his U.S. citizenship. After the war, he eventually returned to San Francisco and became a social worker, then a social work professor at San Francisco State University, while talking openly about his camp experience.

I’ll conclude with one other notable 100th anniversary: On May 24, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924 into law, banning further immigration from Japan. The ramifications of this law—from setting the U.S. and Japan on a path that led to war seventeen years later to profoundly influencing the demographics of the Japanese American community—would be felt for generations. As immigrants continue to come under attack today, it is worth remembering our one hundred year old folly, and taking a cue from some of these Nisei notables in working to ensure it’s not repeated.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

Author’s note: As with previous years, there are some here who are not technically Nisei by the literal definition, but given their age, all would be culturally Nisei (or Kibei) and all would likely identify as Nisei.

Read about previous years’ Nisei Notables here.

[Header: A toddler in a high chair with a large birthday cake with two candles that reads “Happy Birthday Marian,” c. 1940s. Courtesy of the Frank Miwa Collection, Densho.]