June 7, 2022

We’re delighted to introduce Densho’s 2022 Artist-in-Residence cohort! This year’s call for artists garnered more submissions than ever before and it was incredible to see all the creative ways y’all are using our archives and keeping the story of WWII incarceration alive. While we’re only able to offer two formal residencies, we added on a Community Curator position to this year’s artist cohort. Their role will be to highlight other artists over the coming year, so be sure to keep an eye out for more art and history related content coming your way soon! For now, read on to meet our 2022 artists and community curator in residence!

Matthew Okazaki, Artist-in-Residence

Matthew Akira Okazaki (he/him) is an interdisciplinary artist and educator whose practice focuses on themes of longing and belonging. Formally trained as an architect, Okazaki takes materials and processes found in architecture to explore the relationship between parts and wholes, and the blurs between. By creating objects and images that explore the ambiguous territory of the threshold, Okazaki tries to capture our own struggles with reconciling our individual and collective identities through works that are simultaneously stable and precarious, familiar yet foreign.

For his residency project, Okazaki will use photographs and records found in the Densho archives to create a series of scale models that seek to recreate the domesticity of WWII concentration camps. He will begin by examining the architecture of the camps themselves, and reconstruct some of the barracks in different stages of completion. He will photograph these models, and then layer images from the archives on top of these reconstructions. The final product will be large format prints of these multimedia layered “collages.” In addition to sharing his work with Densho audiences via digital media, he hopes to exhibit this work in the Boston area so that students and the general community can view them.

He cites his grandfather as inspiration for this work. In his residency proposal, he wrote:

“My grandfather spent his youth in the American concentration camps of World War II. They stayed in horse stables and converted army barracks. He says that there was so much dust. In the middle of the war, in the middle of the desert, surrounded by barbed wire fences and outposts and armed guards, it was a place-between, where the conflict of identity was made manifest. A placeless place for those inexplicably extracted from their former lives, from their former selves. Barren architectures in barren landscapes, these “homes” were hardly that — blank walls, a stove, a lone light bulb — devoid of any semblance and sense of a domesticity. And yet, despite the incredible trauma, looking back my grandfather told me he sometimes took comfort there in the desert. Perhaps much of this can be attributed to the resilience of the people imprisoned, who quickly began making furniture, toys, curtains, and keepsakes from scrap lumber and found objects. They began gardening in the yards, transforming areas into impossibly lush oases in these desolate regions. Here, by transforming the sterility of the desert and the architecture into makeshift homes, an act of quiet rebellion had taken place. A form of perseverance, of gaman, not to be viewed as reactive, but as a radically projective act. For people like my grandfather, like it or not this was home, and so a home it would become.”

Learn more about his work at matthewokazaki.com.

Kanon Shambora, Artist-in-Residence

Kanon Shambora (she/they) is a multi-disciplinary artist based in New Jersey. Shambora is a recent graduate of Colby College (Maine), where she earned a degree in studio art (concentration in printmaking) and East Asian studies. Shortly after earning her Bachelor’s, she worked within her school museum’s exhibitions and publications department. She now works part-time as a teaching artist in her local community arts center and is pursuing a career in art-making in Mercer County, New Jersey. Her work often deals with matters of family, community, childhood, place, and memory.

For her residency, Shambora will highlight agricultural worker exploitation and related material objects produced before, during, and after incarceration.

In her proposal, she wrote:

“This country relies on immigrant labor to produce a bulk of our necessities, especially when it comes to farming. Prior to WWII, almost two-thirds of Japanese Americans in the West Coast worked in agriculture. I would like to pull from the Densho archives records of people’s lives before they were relocated, focusing specifically on crop production. Using the medium of printmaking, I will then reproduce hundreds of images of these crops, printed in an overlapping manner. The point of this is to call attention to the way in which incarcerees’ lives were uprooted, the resulting farming shortages, and the way in which we take advantage of our farm workers. I would then compare this to American agricultural production today, depicting crop production by current immigrants.”

Shambora shared additional thoughts about why she was motivated to apply for this residency:

“Growing up on the East Coast, I was very fortunate to have been surrounded by a strong, local Japanese community. Almost everyone I knew who was of Japanese descent recently immigrated here, so their kids (the kids that I grew up with) are first generation Japanese Americans. My community here does not share a direct lineage to incarceration history, and it was seldom talked about in our local public schools. I was drawn to this residency because I not only want to educate myself about Japanese American history but also because I want to pay homage to those who have paved the way for current Japanese communities to thrive. Their resilience is the reason why my mother, her friends, and their children were able to have a fulfilling life here. The violent nature of our country’s history affects poor and marginalized communities to this day, and I believe this practice of reflecting upon incarceration can also be a tool for confronting the structural inequities that continue to persist.”

Kanon plans to document the residency and her process of developing her project on her Instagram account, so give her a follow at @kan0nshamb0ra! View some of her previous work at kanonshambora.com.

Erin Shigaki, Community Curator

Erin Shigaki, one of Densho’s first artists-in-residence back in 2018, returns as our inaugural Community Curator. Over the course of the coming year, she will select six working artists from all genres and career levels to feature on the Densho website and social media.

Erin Shigaki (she/they) is a yonsei (fourth-generation) Japanese American born and raised in Seattle, WA. She creates murals and installations that are community-based and focused on BIPOC experiences, often the WWII incarceration of her family and Japanese American community. She is passionate about highlighting similarities between that history and systemic injustices communities of color continue to face. She is keen to understand intergenerational trauma and to explore the emergence of beauty and intimacy despite unspeakably harsh circumstances. And she believes that wielding art and activism to tell these stories can educate, redress, and incrementally heal.

Erin is also a community activist and helps run an annual pilgrimage to Minidoka, the American concentration camp where her family was incarcerated. She is active with Tsuru for Solidarity, a nonviolent, direct action abolitionist project of Japanese American social justice advocates. She also serves on the board of Look Listen + Learn, a public access television show that inspires radical Black joy and advances early learning in young children of color. All of this work is fundamental to her artistic practice.

Explore more of Erin’s work at www.purplegatedesign.com.

—

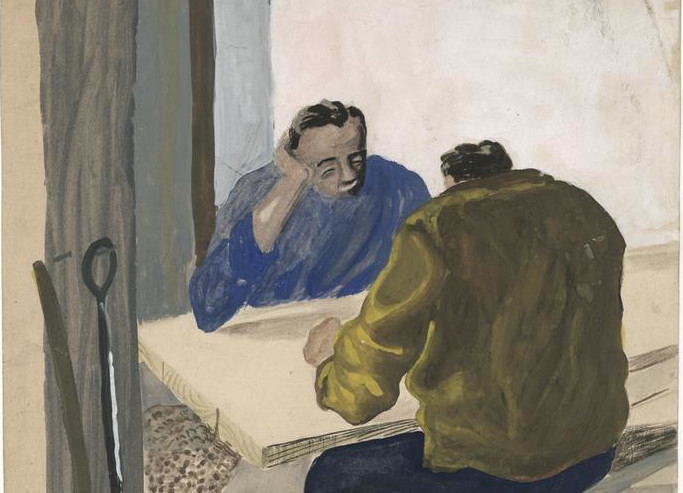

[Header: A painting titled “Playing Go in the furnace room in Minidoka,” by Art Mayeno. Courtesy of the Mayeno Family Collection.]