October 6, 2025

Guest post by Rob Buscher

Located in South Texas about 80 miles southwest of San Antonio and 40 miles east of the Mexican border, Crystal City Family Internment Camp opened on November 2, 1942. This detention site held over 4,000 incarcerees during the period it operated until January 1948. Conceived of as a family reunification center, the prison camp was jointly administered by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). Some of the Issei who were arrested under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 were eventually transferred here. The site was unique for many reasons, notably as one of the few WWII detention centers that held persons of Japanese, German, and Italian ancestry at the same time during the war. Other prisoners included Japanese and German Latin Americans.

Here are ten little-known facts about the Crystal City camp, its origins, and the experiences of those detained there during WWII.

Popeye Is the Town Mascot

In the 1930s, the town of Crystal City became one of the country’s leading producers of spinach and began using the slogan, “Spinach Capital of the World.” By 1936 Crystal City hosted its first annual spinach festival, a tradition that continues until current day. Known for his love of spinach, Popeye the Sailor Man became the town’s unofficial mascot when a statue of Popeye was erected in 1937 outside of its city hall. Due to his popularity in the prewar era, Popeye was used in several national wartime anti-Japanese propaganda campaigns including a US war stamps poster and a 1942 animation titled, “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap.” Del Monte Corporation built a major spinach canning plant northwest of the town in 1945, which continued operations until 2019. Today statues of Popeye can be seen in several locations throughout town, and his image is prominently featured on spinach festival merchandise.

Built on the Grounds of a Former Mexican Migrant Worker Camp

In the 1930s, the majority of Crystal City’s approximately 6,000 residents were migrant laborers of Mexican heritage. Migrant laborers would typically travel throughout the state following the work wherever it was available during various planting and harvest seasons. They made their homes on land owned by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) on the edge of town. Known to some of the Spanish-speakers as El Campo, the poorly furnished migrant labor camp lacked running water and indoor plumbing. Most of the houses were built from corrugated sheet metal and had dirt floors. This site was included in the 200 acres that INS leased from the FSA to create the Crystal City Family Internment Camp in 1942.

The Last WWII Concentration Camp to Close

Although WWII ended with Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, Crystal City Family Internment Camp remained open until January 1948. Like some of the other DOJ camps, Crystal City was used as a staging facility for Tule Lake renunciants awaiting deportation. Civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins filed a mass habeas corpus lawsuit on November 13, 1945 that resulted in a temporary stay of deportation ruling for nearly a thousand renunciants. However, each case had to be decided on its own merit. While the defendants awaited their rulings, 368 of them were transferred to Crystal City. A separate group of Japanese Peruvians represented by Collins were also held at Crystal City long after the war ended while the US government determined their fate. The last prisoners were not released until more than two years after the war was over.

Detained Latin Americans

After the European war erupted in 1939, the US government posted FBI agents at embassies throughout Latin America to compile information on Axis nationals and potential sympathizers. By 1940, the US took on a direct role in regional security in Latin America, establishing the Emergency Advisory Committee for Political Defense. Composed of representatives from the US, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Uruguay, and Venezuela, the Committee sent a list of recommendations to the governments of Latin American countries on how they could better secure the hemisphere. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the US government convinced 18 Latin American nations to allow the extrajudicial rendition of persons of Japanese, German, and Italian ancestry residing in their countries. This resulted in the kidnapping and human trafficking of more than 2,200 Japanese Latin Americans, over 4,000 German Latin Americans, and several hundred Italian Latin Americans.

Entire families were taken from their homes and forced aboard US military transport ships from their countries of origin to the Panama Canal Zone. From there, they were taken by ship to the port of New Orleans. Upon arrival, their travel documents were confiscated and destroyed, and they were told they had entered the US illegally. They were then detained under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, with plans to use them as hostages in a prisoner exchange with Axis nations for US civilians trapped behind enemy lines when the war began. Crystal City was one of several camps used to imprison these individuals, who were transported there from New Orleans. They traveled overland 650 miles by train and bus, with some of the Japanese Peruvians unsure of what country they were in. About two-thirds of the total population of Japanese Latin Americans kidnapped by US agents in Latin America were imprisoned at Crystal City, the majority of whom were Japanese Peruvian.

Facing intense anti-Japanese prejudice in Latin America, most were never allowed to return to their prewar homes. Many were deported to Japan, while others represented by lawyer Wayne Collins were granted leave to remain in the US. A group of about 200 were hired as laborers at Seabrook Farms in southern New Jersey. Others were able to resettle in San Francisco thanks to Reverend Yoshiaki Fukuda, who allowed several dozen to live at his Konko-kyo Church in Japantown until they found permanent residences elsewhere.

Had Its Own Swimming Pool

Crystal City was one of the few Japanese American confinement sites with a public swimming pool. Designed by Italian-Honduran civil engineer Elmo Gaetano Zannoni, the pool was dug out from a swamp and paved with concrete by German and Japanese laborers. The swimming pool offered a reprieve from the hot Texas sun, with an average summer temperature of around 99°F and daily highs of up to 104°F. Sadly, two Japanese Peruvian girls named Sachiko Tanabe (13) and Aiko Oyakawa (11) drowned there in 1944. In 2023, a memorial marker was erected at the former site of the swimming pool by the Crystal City Pilgrimage Committee with help from town officials.

Allowed Integrated Prison Schools During Jim Crow

As a Jim Crow state, Texas still practiced legal segregation in their school districts and other public facilities during the 1940s. Despite this fact, high school students at Crystal City Family Internment Camp had the option of attending the integrated Federal High School, regardless of race or nationality. Since many families incarcerated at Crystal City were planning to repatriate to either Japan or Germany, they often sent their children to the Japanese or German language schools where the curriculum was based on their respective overseas educational standards. However, Japanese families with Nisei children who wished to remain in the US were permitted to enroll them in the English language Federal schools, alongside German Americans. The education at Federal Elementary and Federal High School was based on Texas state curriculum. Federal High offered softball, basketball, and football as extracurricular sports. High school students produced their own yearbook and also published a school newspaper.

Housed a German Beer Hall

As a detention site created to imprison foreign nationals, Crystal City was held to the standards of the Geneva Convention on the treatment of prisoners of war. While alcohol was forbidden in the War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps that housed the majority of Japanese Americans, German internees were actually permitted a weekly beer ration at Crystal City. There are many photos and oral histories related to the German beer hall on the German American Internee Coalition’s website. At least one Nisei musician was known to play piano there on occasion, but whether the inmates of Japanese ancestry were also permitted to imbibe alcohol there is not documented. Alcohol was also allowed at other large INS and US Army operated detention sites including Fort Lincoln, Santa Fe, and Lordsburg, where prisoners were being held under the Alien Enemies Act.

Some Families Had Their Own Kitchens

While Crystal City did feature some barracks style buildings and communal mess halls, the camp was unique in the types of single-family housing that were built to accommodate family reunification under the rules of the Geneva Convention. These included prefabricated Victory Huts, duplexes, and quadplexes. Some units had indoor plumbing and most had kitchens with kerosene stoves and iceboxes. Families with their own kitchens were permitted to shop for groceries using ration coupons that were distributed on a monthly basis, and cook their own meals at home. Compared to the erosion of traditional family structure that many Japanese Americans experienced in the communal mess halls at the WRA camps, this may have helped Crystal City internees better preserve their prewar family dynamics.

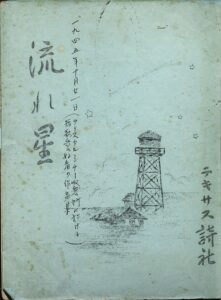

Had Its Own Tanka Poetry Club

The prisoner population at Crystal City also included Issei arrested under the Alien Enemies Act in Hawai`i. Among those from the Japanese Hawaiian community was Dr. Motokazu Mori, a Honolulu-based physician who was an avid poetry writer and member of several Hawaiian literary clubs. Arrested by the FBI after the war broke out, Dr. Mori was detained at Sand Island and several other prisons on the US mainland. He was eventually reunited with his wife, Dr. Ishiko Shibuya Mori, at Crystal City in August 1943. Together, they formed a tanka poetry club called Tekisasu Shisha, with another Hawaiian Issei named Sojin Takei, an accomplished writer and poet who had worked as principal of the Keahua Japanese School on Maui before the war. They held regular meetings of the Tekisasu Shisha with other internees and toward the end of the war, Mori and Takei compiled an anthology collection of poems written by their club. Titled Nagareboshi (shooting star), the anthology was published in camp using a mimeograph shortly before Dr. Mori returned to Hawai`i in December 1945. At least two known copies survive in the archives of University of Hawai`i at Manoa Library and the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai`i.

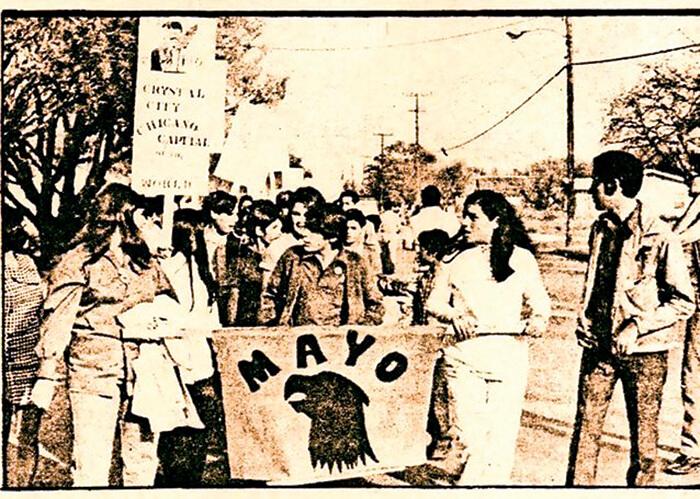

Crystal City Held an Important Chicano Movement Student Walkout in 1969

After the war ended, most of the temporary structures at Crystal City Family Internment Camp were dismantled. Those that remained were given to Crystal City’s municipal government to be adaptively reused by the Crystal City Housing Authority and school district. Local elementary students continued learning in the old German School building well into the 1960s, and some residents still live in former camp dwellings. After Del Monte expanded their canning operation in 1945, the town’s business community continued to flourish for several decades. However, many of the local residents continued to live in poverty. Despite being the majority population, Mexican Americans were regularly discriminated against by the influential white minority who held positions of power as business owners, elected officials, and school administrators. Intimidation tactics were used to keep Mexican Americans out of local politics. One example is Manuel Palacios, a decorated WWII veteran who returned home from the war and registered as the first Mexican American to run for Zavala County Sheriff. In broad daylight, a Texas Ranger beat Palacios over the head with a pistol, leaving him bloodied and threatening further violence if he did not remove his name from the ballot.

Until the late 1960s limited segregation was still being practiced in the school district, with Mexican American students restricted from eating their lunches in the school cafeteria alongside their white classmates. Instead, they had to eat outdoors on picnic tables in the midday Texas sun. Mexican Americans were also limited to a single token member of the school sports teams and cheerleading squad. Students caught speaking Spanish in school were even beaten by their teachers on a regular basis. The final straw occurred in 1969 when the two most talented cheerleaders, who were both Mexican American, were denied a spot on the cheer squad. In response, a group of students organized a walkout on December 9, 1969 to protest their mistreatment.

The walkout generated enough attention that Senators Ted Kennedy and George McGovern met with the students. By January 9, 1970, the school board agreed to student demands including the hiring of more Hispanic teachers, access to culturally competent education, bilingual learning resources, greater curriculum inclusion of Mexican American history, and a student representative on the school board. In the following election cycle, Mexican American candidates running under the progressive third party La Raza Unida Party swept both the school board and city council elections. Crystal City would continue to be an important site for progressive Chicano Movement organizing in the decades to follow.

Today, the history of the 1969 walkout is memorialized at the My Story Museum in Crystal City, the town’s first local history museum that opened in November 2024. Operated by Diana Palacios, one of the cheerleaders who was denied a spot on the cheer squad in 1969, the museum also tells the broader history of Zavala County Texas, commemorates local veterans, and features the only permanent exhibition on Crystal City Family Internment Camp. Titled “America’s Last WWII Concentration Camp” the exhibit was developed by a committee of Japanese American and Japanese Peruvian incarceration survivors and descendants working under the Crystal City Pilgrimage Committee. CCPC organizes semiannual pilgrimages to the site, and works closely with the Mexican American residents of Crystal City to steward these shared histories.

—

Rob Buscher is a film and media specialist, educator, curator, and published author. Since 2017 Rob has lectured at University of Pennsylvania’s Asian American Studies Program, where he teaches courses on cinema and activism. He is the producer and host of Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation’s thirteen-episode podcast Look Toward the Mountain, and host of PBS WHYY’s six-episode television series Asian Americans & Pacific Islanders: A Philadelphia Story. Rob is currently co-producing a feature-length documentary Kiyoshi about Sansei HIV/AIDS activist Kiyoshi Kuromiya, in partnership with William Way LGBT Center. Rob works with the Crystal City Pilgrimage Committee as a communications and public history consultant on the first permanent exhibition on wartime incarceration in Texas, “America’s Last WWII Concentration Camp” at the My Story Museum in Crystal City.

[Header: Three children stand on a dirt road between rows of houses in the Crystal City internment camp, c. 1943. Courtesy of California State University, Sacramento, Department of Special Collections and University Archives.]