June 3, 2025

In March 2001, while at a Medal of Honor Ceremony to recognize Private First Class William K. Nakamura and Technician Fifth Grade James K. Okubo, Seattle Mayor Paul Schell reflected “Nothing can be done to atone for the fact that our government devastated [the Japanese American] community, then took away their sons to fight in a foreign land. The lessons learned during that period in our country must never be forgotten.”

Nakamura and Okubo were both forced into concentration camps with their families after the enactment of Executive Order 9066. Each volunteered for combat, and both were posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Nakamura was incarcerated at Minidoka and was later killed in action while serving in Italy in 1944. Okubo survived the war after leaving Tule Lake and treating injured men under enemy fire while serving as a combat medic in France.

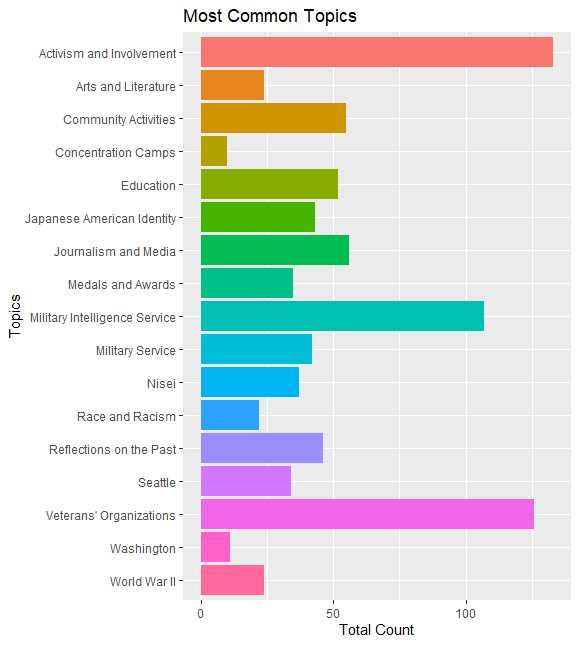

Both men’s accomplishments were recognized and “honored 56 years too late,” in the words of the accompanying Seattle Times headline. Japanese American military accomplishments had been overlooked due to discrimination after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, but the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) Northwest Association, a veterans group for former members of the MIS residing in the Pacific Northwest region, worked to ensure that Japanese American history would be remembered and honored. The Military Intelligence Service Northwest Association collection contains the copies of the MIS Northwest Association membership newsletter, newspaper clippings highlighting its community engagement, and documents related to the running of the organization. Many common ‘topics’ or subjects tagged throughout the material in the collection are displayed in the data visual below.

As seen above, “activism and involvement” and “education” are prominent themes, as the association prioritized legacy and remembrance through historical preservation and educational outreach. The Military Intelligence Service was composed mostly of Japanese Americans who served as linguists during World War II. They helped interrogate Japanese prisoners and acted as translators, but because of the “extreme secrecy of this intelligent work, these fascinating facts have only recently come to light,” explained author of the 1994 book Honor by Fire Lyn Crost.

Military Intelligence Service veterans prioritized documenting and sharing MIS experiences with schools and communities to promote understanding and preserve history. In addition to contributing research to Crost’s work, members of the MIS Northwest Association also published an organization history in 1996, “Unsung Heroes: Military Intelligence Service: Past – Present – Future,” and collaborated with Dr. James McNaughton, an army historian, to compile an official history of the MIS titled “Nisei Linguists : Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service during World War II” in 2007.

Not only did the MIS Northwest Association advocate for recognition of military accomplishments like the above-mentioned Medal of Honor Ceremony, they also supported cultural and historical projects. Members helped create the historic Kubota Garden in Seattle and installed a commemorative plaque for MIS Veterans in the Kawabe House Garden. They participated in oral history projects to preserve the legacy of WWII MIS veterans, and collaborated with the Seattle Public Library to host an exhibit on contributions of the MIS during WWII.

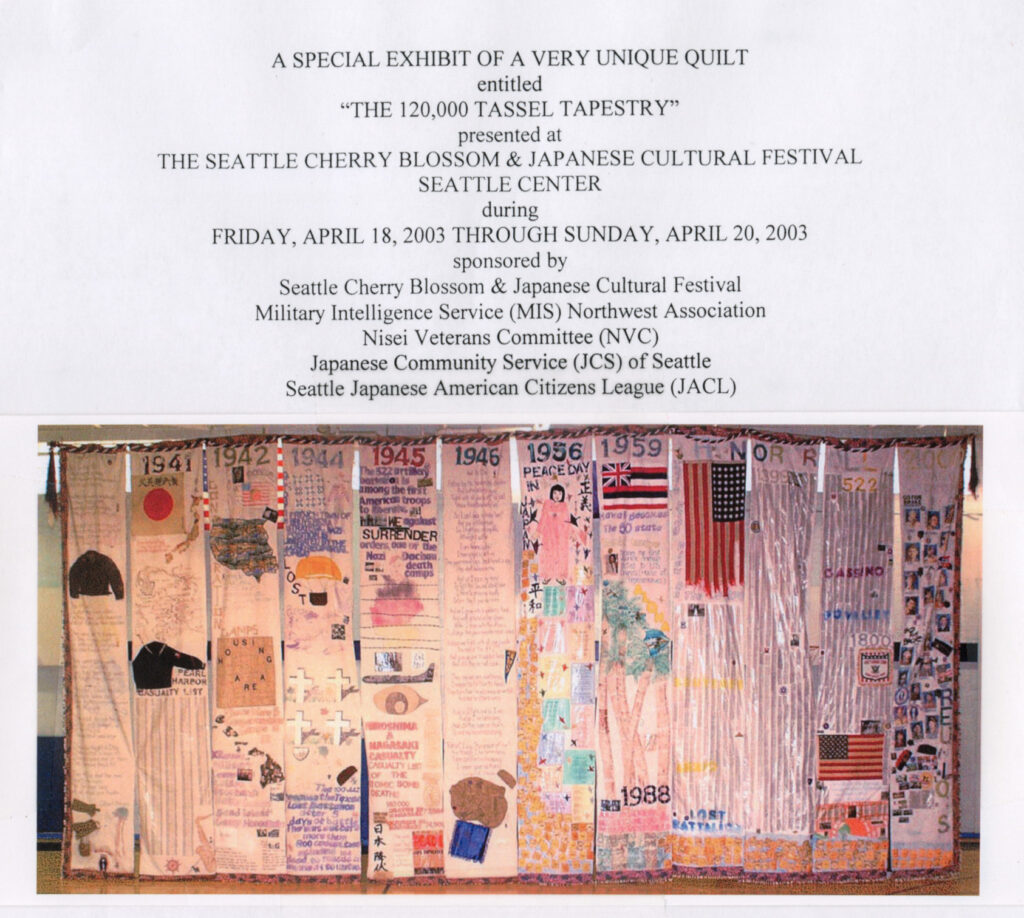

Other “community activities,” a frequently used tag throughout the collection, promoted by the MIS Northwest Association include a Cherry Blossom Dedication in Seattle Center for the 50th Anniversary of World War II and the coordination of a display of the “120,000 Tassel Tapestry,” a quilt created by middle school students in Indiana to illustrate the Japanese American experience during World War II, at the 2003 Seattle Cherry Blossom Festival.

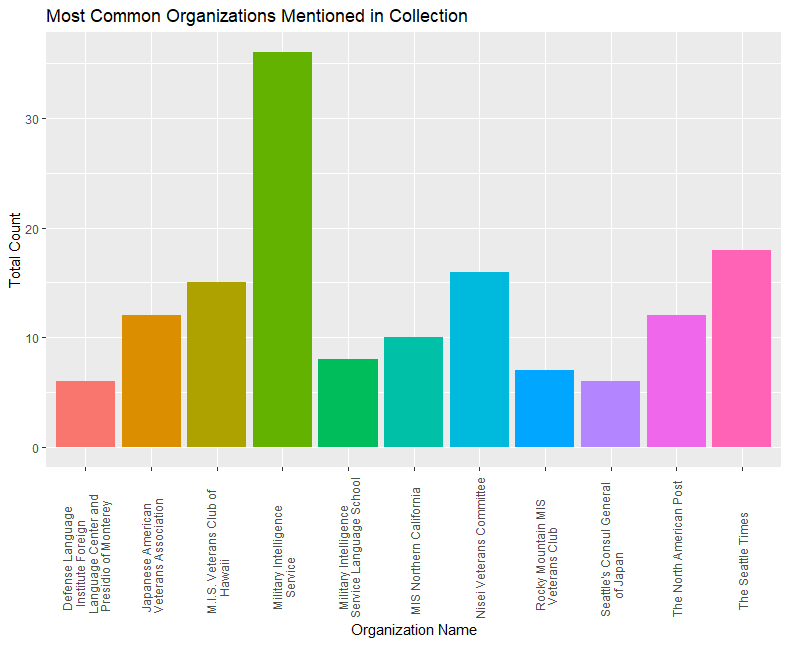

The MIS Northwest Association collection also emphasizes collaboration and engagement with other Japanese American organizations, such as other branches of the Military Intelligence Services veteran organization (like the MIS Northern California, Rocky Mountain MIS Veterans Club, and the MIS Veterans Club of Hawaii), Japanese American Veterans Association, Nisei Veterans Committee, and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

Multiple Japanese American veteran organization branches worked together to hold national reunions, including a 1993 event in Washington, D.C. which included tours of national monuments and panels to discuss personal experiences of MIS veterans and their contributions to WWII. Prominent figures like President Bill Clinton and Senator Daniel K. Inouye were invited. Additionally, the 1995 reunion hosted in Seattle commemorated the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II and the return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast after being displaced by Executive Order 9066.

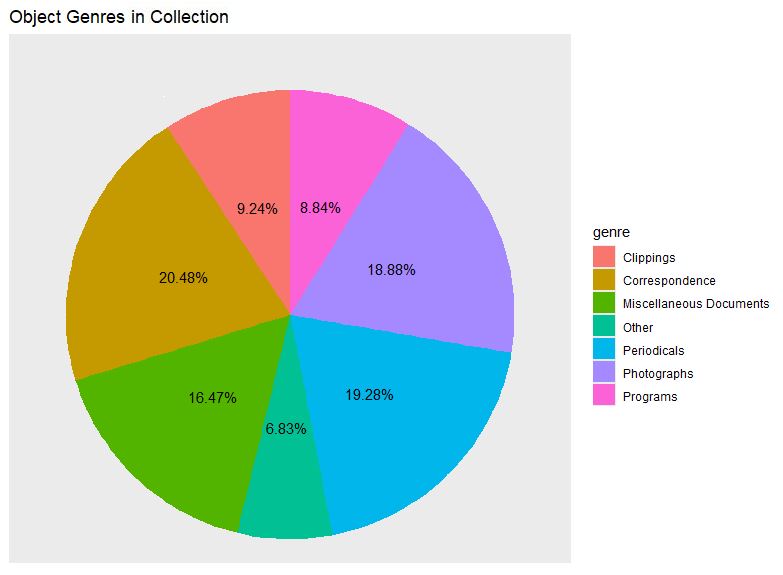

After the MIS Northwest Association disbanded, the former president collected newsletters from the MIS Veterans Club of Hawaii, which still operates today. Collaboration with other organizations mentioned in the materials often focuses on projects to document and share Japanese American military history, often through educational documentation and programming. Although there are multiple newspaper clippings within the collection—as indicated by the common mentions of the Seattle Times and North American Post in the ‘Most Common Organizations’ data visualization—correspondence, periodicals, and photographs are the most common object genres within the materials.

Members saved photographs of MIS-related events and multiple newsletter periodicals helped to preserve their written history. Staff of the MIS Northwest Association corresponded regularly with other MIS veteran organization branches, Seattle cultural heritage organizations, and even members of Congress. Correspondence relating to the campaign to change the MIS logo from a gopher wearing a Native American ceremonial headdress to a shield following criticism from the American Indian Movement and the Indian Council of Minneapolis can also be found in the collection. Fern Mathias, Director of the Southern Californian American Indian Movement, contacted the MIS Northwest Association about the original MIS logo and explained the discriminatory nature of the imagery. Mathias urged the president of the MIS Northwest Association to stop perpetuating the use of the harmful stereotype, and by 1997 multiple branches of the organization voted to change the logo to a red, blue, and gold shield.

The group dissolved in December 2004 after nearly 25 years, due to dwindling membership. Its assets and historical materials were distributed among the Wing Luke Museum, Densho, the Nikkei Heritage Association, and the Nisei Veterans Committee. The legacy of the MIS Northwest Association lives on through the historical preservation, educational outreach, community engagement, and advocacy efforts now carried forward by these cultural heritage organizations. Their work ensures that despite the injustice of wartime incarceration and discrimination by the U.S. government, the contributions and experiences of Japanese Americans in the twentieth century—both in civilian life and military service—are remembered and honored.

—

By Kathryn Bolin, Densho Archives Intern