May 1, 2025

This May Day—also known as International Workers’ Day—we take a look back at the intersection of labor history and Japanese American incarceration during World War II.

Japanese Americans were expected to help build and maintain the concentration camps where they were held, as well as grow some of their own food to offset the costs of their imprisonment. While many welcomed job opportunities within the camps—whether for the pay or to gain experience, or simply to have something to do to pass the time—the working conditions and paltry wages offered by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the government agency responsible for managing the camps, left much to be desired.

Inmates were often not provided with adequate equipment to safely do their jobs, and their diets were insufficient for the physical demands they were expected to meet. There were also tensions and resentment between Japanese American workers and white supervisors and administrators. Worker strikes, stoppages, and slowdowns erupted across almost all of the WRA camps and at least one “assembly center.”

Keep reading for a brief overview of the history of Japanese American incarcerated labor during WWII, and head over to the Densho Encyclopedia for a deeper dive.

Santa Anita Assembly Center

The Santa Anita camouflage net factory opened on May 25, 1942, and from the beginning workers voiced concerns about low wages, health risks, and being “compelled to work.” By June 12, 1,523 Japanese Americans were employed at the factory, but only 1,214 showed up for work. On June 16, some 1,200 workers staged a sit-down strike, complaining their food was not sufficient for the work they were expected to do and their pay rate ($8 per month for “unskilled” labor) was too low. The next day, Camp Director Russell Amory met with the workers, and the army agreed to establish the position of weaver in the skilled classification at $12 per month. However, Shuji Fuji, the author of a pamphlet urging the workers to strike, and other strike leaders were transferred to another camp, and another 25 “recalcitrant workers” were fired by June 22. On the morning of June 18, Amory addressed the camouflage net workers in a special meeting in front of the grandstand and assured the camp population that “legitimate grievances of camouflage net workers will be considered and remedies made.”

Soon after, on June 23, camp dishwashers went on strike after two workers were fired for disobeying a white supervisor’s order about handling the chinaware. They demanded an increase in personnel and supplies like linens and towels, and to be paid for a full 8-hour day. They also complained about the chief steward because he presumably had refused to do the necessary requisitions, had allowed white staff to eat at the mess hall (sometimes leaving nothing to eat for the dishwashers), and was patronizing to the Japanese American workers.

After listening to their grievances, Amory ruled that the chief steward was to remain but promised to re-employ the two dishwashers after a period of time, while explaining the difficulty of recruiting new kitchen staff and warning that incidents like this would sway public opinion to put camps under military control.

Manzanar

The camouflage net factory in Manzanar became a site of labor unrest due to working conditions, wages, and the political meaning of aiding the war effort while incarcerated.

Inmates objected to the fact that Issei were not allowed to work at the factory and were thus shut out from higher wages. Working conditions were difficult, as the net making work generated much lint that caused skin irritation and breathing difficulties. “The dust and the lint from the burlap would fly around,” recalled Sue Kunitomi Embrey. “We had masks, but I don’t know how much help they were.”

The administration set a quota of five nets per crew per day, after which workers would be allowed to leave. As workers became more proficient, they began leaving early. The administration then tried to enforce an eight-hour work day for the net factory. As a result of this and the prohibition of the Japanese language at meetings, 670 net workers walked out on August 12. The factory reopened five days later, with the compromise that the rest of the eight-hour day after the quota was reached would be filled by training classes.

Minidoka

Due to a cutback in inmate workers in 1943 and other factors, much labor unrest took place in the last two years of Minidoka.

In January 1944, a strike by some 160 boilermen and janitors left inmates without hot water for a week in the dead of winter. They were protesting a dramatic decrease in the workforce that forced remaining workers into longer hours.

Similar work stoppages took place with mail carriers, warehouse workers, garbagemen and others. Cooks staged slowdown strikes in 1945 in protest of administration plans to close mess halls as block populations dropped. Workers building the high school gym also engaged in slowdowns that resulted in the gym never being completed.

Topaz

Just a few days after the arrival of the first “volunteer” group on September 11, 1942, kitchen workers charged with preparing the mess halls for the mass arrival of inmates from Tanforan walked out over a conflict with their white supervisor. The strike continued for three days, until an agreement was reached that limited the supervisor’s authority over them. A year later, in September 1943, garage workers, also upset about treatment by a supervisor, staged a walkout that spread to include agricultural workers as well and lasted a week.

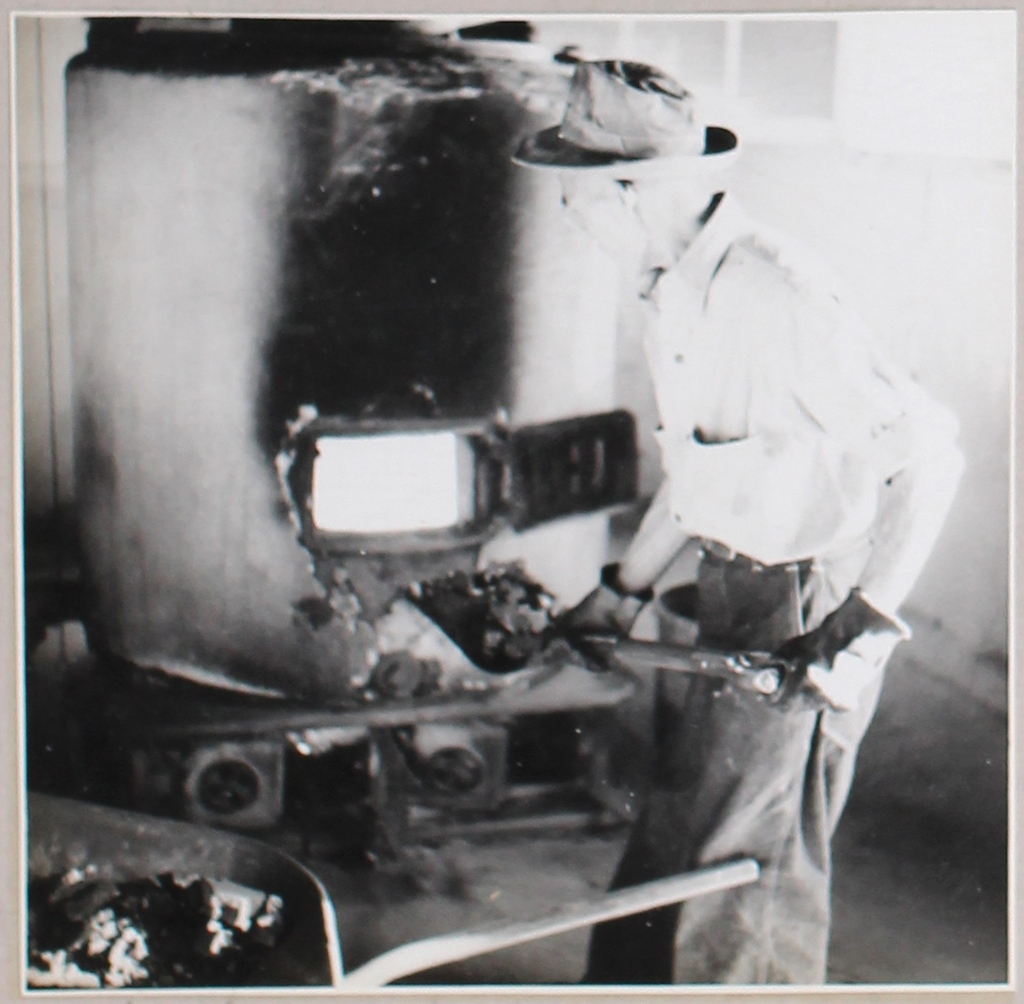

Topaz was plagued by corroded and leaking water and sewer pipes that required frequent repair, a difficult and dirty job. Inmate workers walked off the job in the summer of 1944 over clashes with white supervisors and a wage cut from $19 to $16 a month. Though the higher wage was restored and the overtime policy retooled, it remained difficult to find workers to repair the pipes.

The most notorious incident to take place at Topaz—the fatal shooting of Issei inmate James Hatsuaki Wakasa by a watchtower sentry on April 11, 1943—also touched on labor issues in the camp, when the shocked and outraged Japanese American population responded with a mass strike of inmate workers.

Heart Mountain

On September 6, 1942, the frustration of late food deliveries, thefts, and incompetent or unsympathetic supervisors drove an inmate cook to physically attack a white worker with a kitchen knife.

Amidst rising tensions, the army attempted to recruit volunteer workers to construct a barbed wire fence around the perimeter of the camp. The majority of working-age men went on strike, refusing to participate in the project. Three thousand inmates signed a petition “charging that the fence proved that Heart Mountain was indeed a ‘concentration camp’ and that the evacuees were ‘prisoners of war.'”

The following year, on June 24, 1943, more than 100 hospital employees participated in a walk-out, resulting in a five day strike.

Jerome

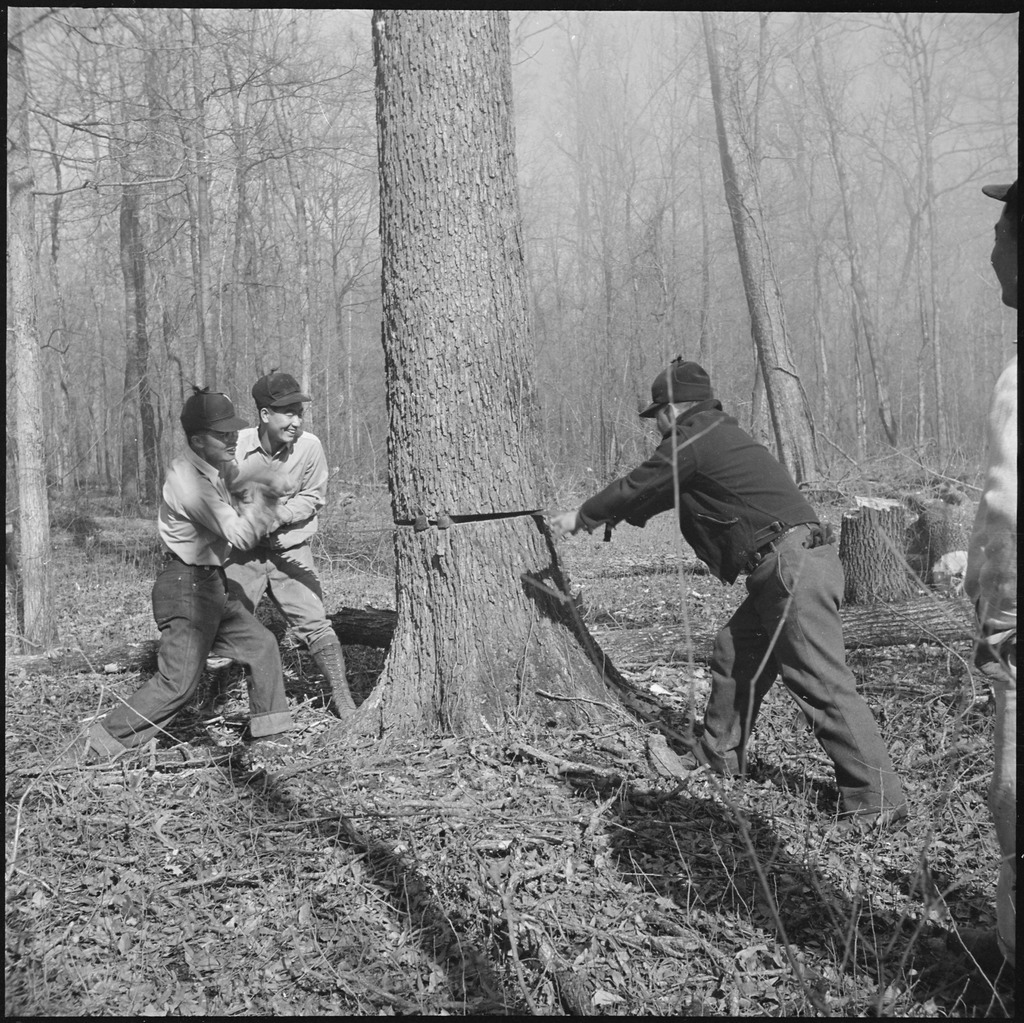

Camp administrators insisted that inmates cut wood from the surrounding forests to provide fuel for the stoves that heated their barracks. The inmates—the vast majority of whom had no prior experience—objected to being compelled to do this physically demanding and dangerous work. As early as November 19, 1942, tree cutters launched a strike over the quality of lunches and dissatisfaction with the paltry WRA wages. Camp Director Paul Taylor agreed to bump wages from $12 to $16. A month later, six wood cutting crews totaling about 75 men started a work slowdown, resulting in Taylor firing them. The wood cutting situation was described as “dire” by January 1943, and further coercion and the shifting of other workers to wood cutting duty followed.

Unrest soon spread beyond the wood cutters. In April 1943, a dispute between inmate workers in the motor pool and their white supervisor led to the firing of two inmate foremen. Thirty of the thirty-four mechanics and shop workers walked off the job.

Then in October 1943, after a trailer carrying inmate woodcutters to their jobs overturned, killing one man and sending twenty to the hospital, calls for a general strike circulated. Labor organizers put up flyers in the latrines calling for a general strike on October 25 and demanding better working conditions, higher wages, backup supplies of coal, and the removal of Taylor. Though the strike did not occur, the organizers did get one of their demands, as Taylor resigned as director a month later.

Rohwer

As at other WRA camps the meager wage scale led to both overt and subtle labor protests. Operations Director James F. Rains wrote that while inmate workers “made excellent progress” when building school buildings or other types of construction that would benefit the Japanese American inmates, they “had a tendency to loaf on the job” when building housing for white administrators.

In a 1943 report on labor unrest stemming from the Reports Office, the office noted resistance against a stricter timekeeping policy meant to curb the “inclination to start to work late, to quit early, and to kill time while on the job.” The report notes an incident in which tractor drivers walked off the job for day when questioned as to why the tractors were only running part-time and another in which warehouse workers walked off the job when a man was fired for protesting orders to speed up the unloading of a truck.

As at Jerome, inmates also resisted attempts to coerce them into difficult and dangerous lumberjack work. Given the limited incentives inmates had to do undesirable work, many other similar incidents no doubt occurred.

Tule Lake

There were multiple instances of labor unrest at Tule Lake—including strikes over the lack of promised goods and salaries as early as August 15, 1942, a strike by packing shed workers the next month, and a mess hall workers protest in October 1942.

In the aftermath of a farm truck accident that resulted in five injured and the death of one inmate in October 1943, a work stoppage that began after the accident developed into a strike. Inmates demanded improved safety and working conditions and compensation for anyone injured while working. Camp Director Raymond Best responded by firing the workers and bringing in strikebreakers— “loyal” inmates from the Poston and Topaz concentration camps—to pick the crops ready for harvest. The strikebreakers’ pay was $1 an hour, enabling them to earn in two days what a Tule Lake inmate earned in a month.

Poston

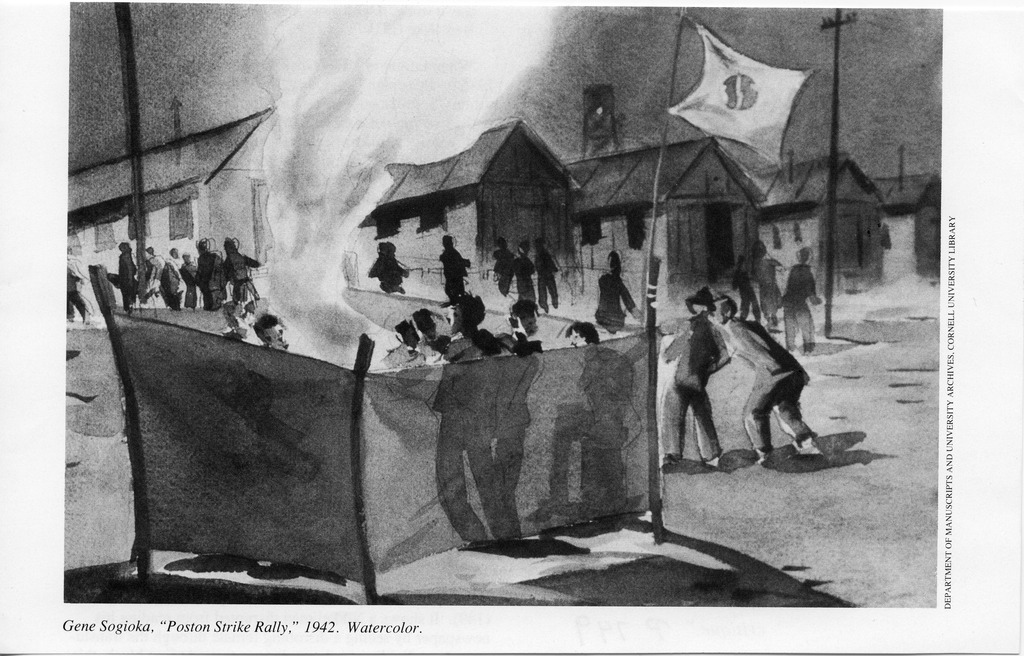

When wage scales were announced shortly after the camp opened, Japanese Americans voiced disapproval over pay, the amount of work expected, and classification of jobs, including an August strike of adobe workers. During the first year of operations, delays in pay, clothing allowances, heating and insulation as colder weather came on, together with the overall injustice of the situation only exacerbated tensions.

One manifestation of these tensions were attacks on individuals suspected of being administration informers. In November 1942, an alleged informer was beaten and seriously injured. The administration responded by holding two Kibei men without charges. Fearing that they would not be given a fair trial, demonstrations were held. After talks broke down, a general strike for Camp I was called, with only necessary services provided. The roughly week long strike ended with an agreement to release both prisoners to the camp, with the stipulations that the beatings would cease and inmates would work cooperatively with the administration.

—

Adapted from the Densho Encyclopedia articles on Santa Anita, Manzanar, Minidoka, Topaz, Heart Mountain, Jerome, Rohwer, Tule Lake, and Poston.