October 26, 2023

As an intern at Densho, I have spent this past summer and fall processing new additions to the Kaneji and Sally (Fujii) Domoto Collection. During that time, I enjoyed getting to know Kaneji Domoto, who created or contributed most of the 1,000 or so items I have been preparing for the archives. When I say “getting to know,” I don’t mean I’ve ever met him. “Kan,” as he was known to friends and family, was born in 1912 and passed away in 2002, long before I became aware of him. But, as anyone who has spent time in archives can attest, there is an intimacy that arises from handling the material artifacts of personal history. My time at Densho has shown me how complex and even painful that personal connection can feel in an archives with a dark throughline: this collection wouldn’t be here for me to witness if Kan and his family hadn’t been incarcerated at Merced and Amache during the war.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Disciple

When I began my project in June I wanted to learn more about who I’d be working “with,” so I took the quick and dirty approach: I Googled him. I soon discovered that Kan completed over 700 projects over the course of his career, working as both an architect and a landscape architect. Most of the articles I found in my initial search featured his contributions to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonia project, a series of homes in New York’s Hudson Valley that combined Wright’s concept of “organic architecture” with the mission of providing modest and affordable homes to the middle class. I also learned that Kan was known for incorporating creative design elements in response to each client’s unique needs, and for keeping costs down by using unglamorous but readily accessible materials such as plywood and industrial piping. I was curious to find out more about the path between the major events in his life: what had it been like to emerge from incarceration and chart a course to success under the wing of a celebrity architect?

Carving a Path

To find out, I had to start at the beginning. As I worked my way through the photographs, correspondence, school report cards, and clippings in the collection, a picture of Kan began to emerge. He was born into a family of landscapers and flower growers, and his years helping out at Domoto Brothers Nursery left him well versed in the workings of both horticulture and business. By his mid-20s his talents were evident, and his skills as a landscaper took him to the East Coast, where he worked on the garden at the 1939 New York World’s Fair’s Japanese Pavillion. It was during this time that he read Wright’s autobiography and developed an interest in architecture. He reached out to inquire about an apprenticeship, and by late in the summer of 1939 he was immersed in a fellowship at Wright’s Wisconsin teaching studio Taliesin East.

This period comes to life in a series of letters from Kan to his sister Wakako back home in California. Page by page, I began to get a sense of his personality—playful, personable, strategic, and self-confident—and I took pleasure in rooting for him as he surveyed his opportunities and honed his skills. But as I tracked the advancing dates at the top of each letter, I couldn’t help anticipating the war that he couldn’t see coming.

A Stark Interruption

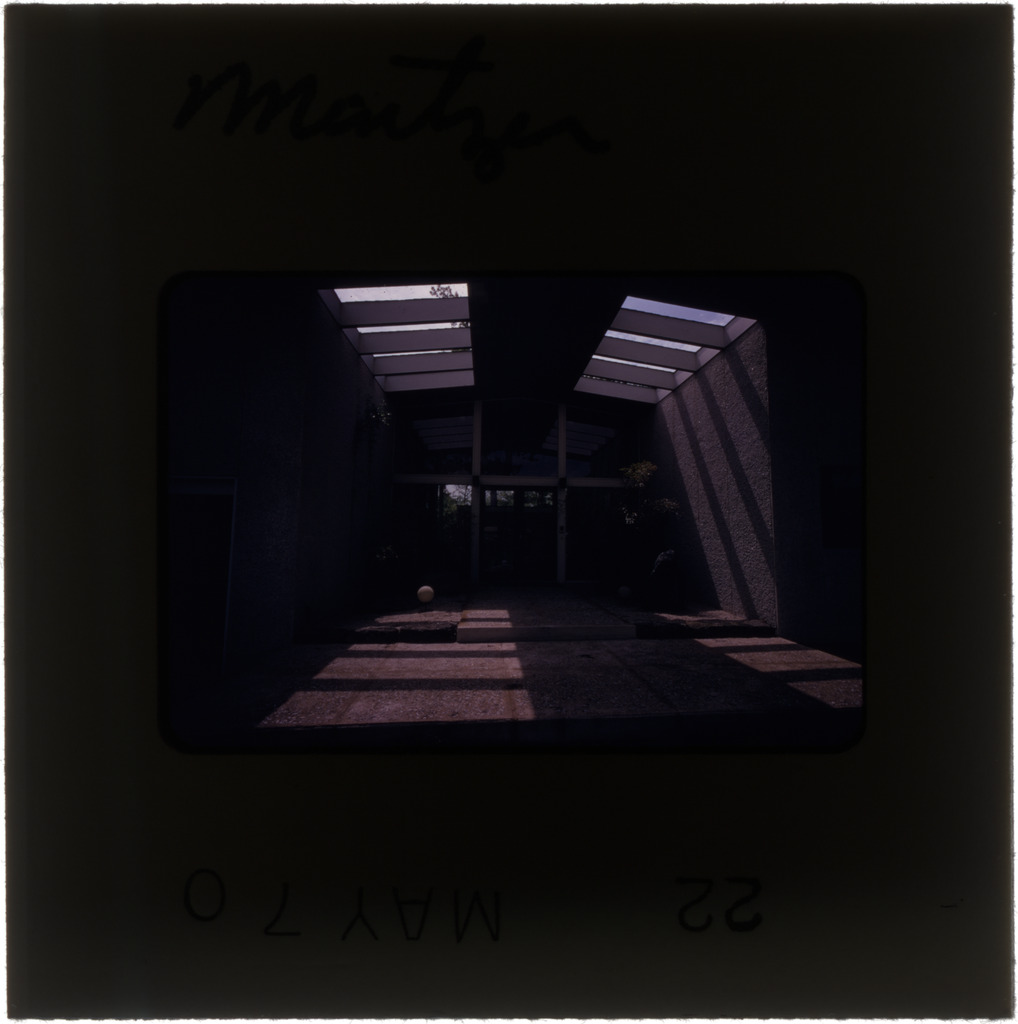

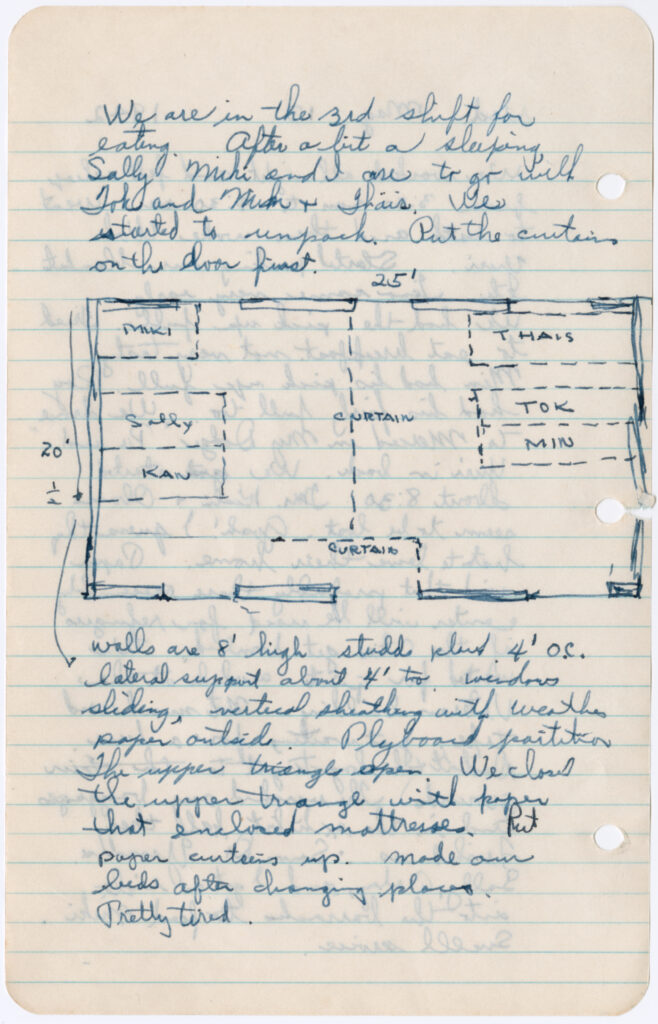

The first six months of Kan’s experience of incarceration—first at Merced and then at Amache—are chronicled in his diary. His writings reveal the unique perspective of an architect’s eye, as he documents the physical spaces that circumscribed his life and the lives of his growing family. At the time he was newly married to Sally Domoto (nee Fujii) and raising their first child, three-month-old Mikiko. They lived in a barracks that he shared with his sister and her family, with a curtain hung to divide the space.

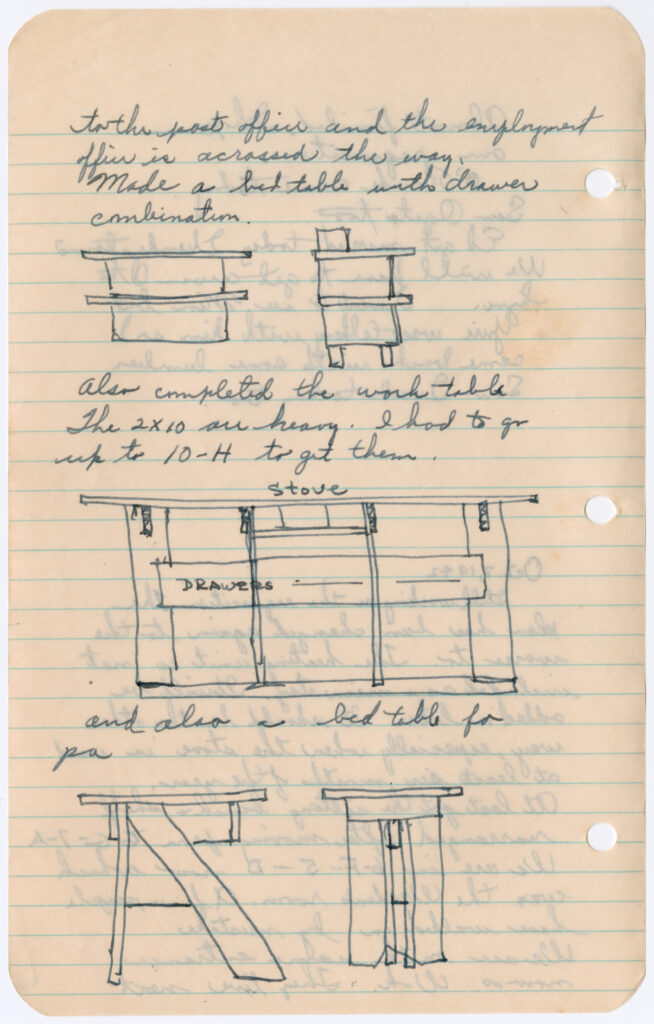

Whatever Kan’s emotional experience of camp, it can only be read between the lines. If he felt any inner turbulence in reaction to the violation of his civil rights he did not record it. The gravity of his situation is implied only through his concise reports of Sally’s fluctuating mood, in which her despair is visible as if glimpsed from the corner of the eye. Instead, Kan used his diary to recount the many productive activities with which he busied himself, as a teacher of architecture and landscaping on the education committee, an organizer of recreational events, and a camp architect and builder. He spent his days sourcing materials, drawing plans, and working on construction crews, and in the evening he used his free time to build furnishings for his family out of leftover wood salvaged from more official projects.

Design as a Humanizing Act

I wonder if Kan gravitated towards building and design work in camp because it gave him a sense of agency. Maybe he took solace in exerting his personal vision over some part of the built environment, when so much else was outside his control.

Ultimately, it’s impossible to know the impact camp may have had on Kan’s inner life, but he has spoken (albeit briefly) about its place in his professional arc. In an oral history conducted by JACL in 1996, Kan credits his time there with helping him develop key skills in carpentry and design. “The experience I had in camp helped me quite a bit,” he explains. “There were a lot of buildings to be done—so I got a lot of practical experience, at $10 a month or whatever they gave you.” (A laughable wage considering hourly pay for union carpentry jobs in 1942 ranged between $1 and $2 per hour.) Indeed, he wasted no time putting his new skills to use, leveraging an offer of employment with Wright to forge a path out of camp for his family. He soon gained recognition as an architect and landscape architect through his work on the Usonia homes.

Though I have not been able to find reflections in Kan’s own words connecting his time in camp with his later work, it still feels possible to infer a resonance. Recalling his reputation for honoring his clients’ unique needs—as reflected in features like low countertops for a client who stood less than 5’ tall, and multiple sinks so that an orthodox Jewish family could more easily keep kosher—I was reminded of the dedication with which he outfitted the plain camp barracks for everyone in his extended family, modifying structures and building furnishings to transform a prison into something more like a home. His commitment to staying within budget by using cheap materials like plywood and fluorescent strip lighting brought to mind the afternoons he spent sourcing recycled materials for projects like a bedside table for his elderly father.

Kan’s signature style bears an aesthetic echo of the design practices he honed out of necessity while at camp, but it also speaks to an ethical sensibility. The homes that he created show the possibilities of compassionate architecture—the opposite of the shoddy, repurposed, dehumanizing structures to which he and his community were relegated during the war. They reveal how design can be a humanizing act: the act of listening deeply to someone and honoring their needs, including their need for beauty.

Making Sense Of Camp And Its Contradictions

A complicated series of emotions arose for me as I worked on Kan and Sally’s collection. Alongside a deep respect for Kan’s resilience, I also felt anger on his behalf. There were moments when I wished that, rather than quietly making the most of the situation, he had articulated a sharp condemnation of his circumstances. Instead, I am learning to accept that camp was and is multiple contradictory things: it was a grave injustice and a smear on American history—and for many people it was a learning experience, a professional training ground, and the seed of future inspiration. (An essential reminder: despite recent remarks by certain politicians, civil rights violations like incarceration camps or chattel slavery can never be justified or excused by the skills that their victims managed to wrest from their experiences.)

Kan is one of many Nisei who rose to prominence for their work in design while taking aesthetic inspiration from the desert, from scarcity, and from the grace of frugality after experiencing incarceration. Maybe instead of asking Kan for anger, I would ask him for a reflection: did the stark landscape of Eastern Colorado feel like deprivation to a young man who had grown up in lush greenhouses, or was he surprised to find a new kind of beauty there? What parts of camp did he take with him when he left?

Sitting with the impressions that this collection has left me with, I find myself attaching importance to two notions: that even when liberty is threatened we can find ways to be the architects of our own lives, and that there is healing to be found in sharing the output of that skill with others.

—

By Densho Archives Intern Evan McGonagill

Evan McGonagill is a mixed Yonsei from Boston, Massachusetts. She has a BA from Bryn Mawr College and is currently pursuing an MA in library and information science with a focus on archival management at Simmons University. Her grandmother was incarcerated at Poston.

This preservation work is supported by the Frank & June Sato Internship Program and by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program.

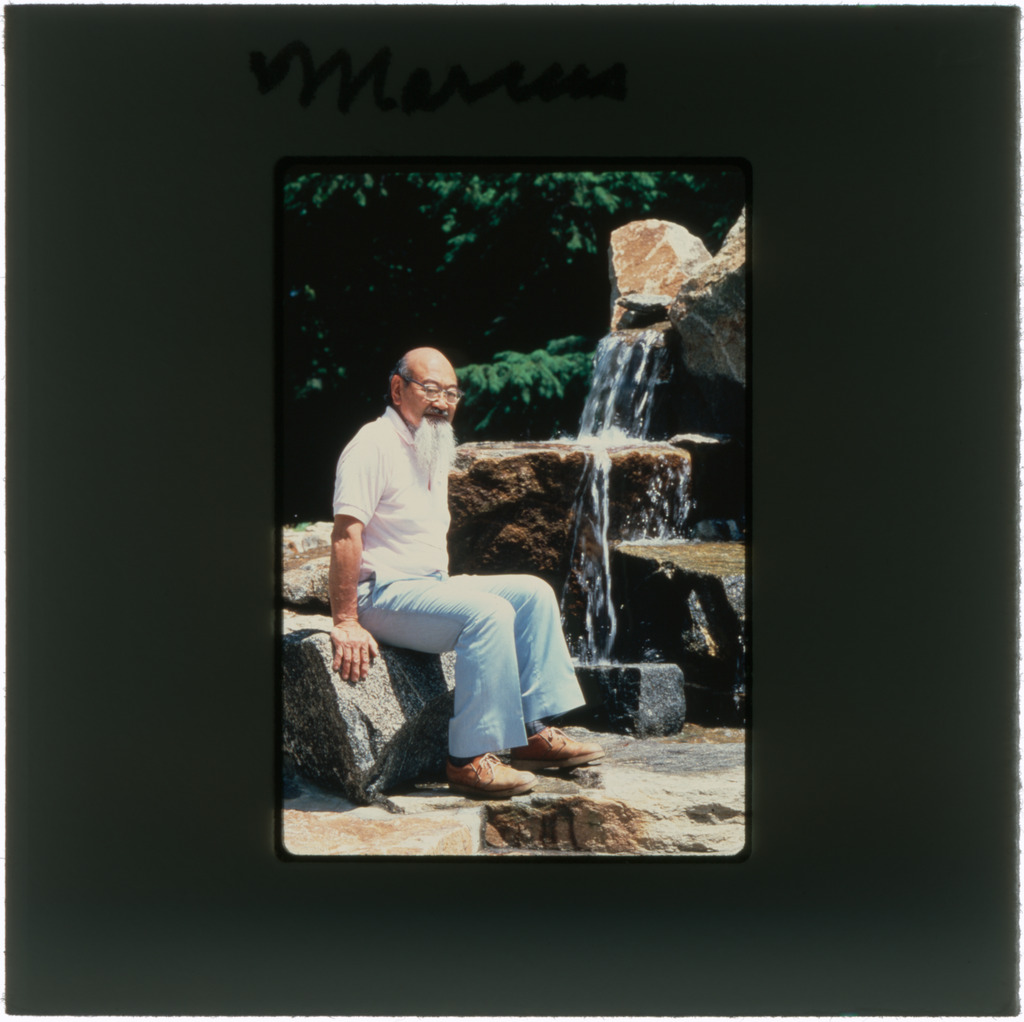

[Header: Kaneji Domoto giving a bonsai demonstration at Hill Nursery in Akron, Ohio. August 1970. Courtesy of the Kaneji Domoto Architecture and Landscape Photograph Collection, Densho.]