February 17, 2016

During World War II, Black and Japanese American fates crossed in ways that neither group could have anticipated. While Japanese Americans were being forced to abandon the lives they’d built on the West Coast, African Americans were in the midst of the Great Migration from the South. During the war, many Black migrants set their sites on the West coast where labor shortages in the defense industry signalled new employment opportunities. Vacated Japanese American neighborhoods provided space for these new arrivals to establish themselves, but the process of putting down roots did not come easy.

Take Los Angeles for example. While Black laborers were welcomed in the city’s defense industries, the lives and families they brought with them were not. Restrictive housing covenants barred people of color from living in white neighborhoods, so the newly vacated Japanese American neighborhood known as Little Tokyo was one of the few places that had space available to arriving African Americans.

80,000 people–most of whom were African American–took up residence in an area that had been home to approximately 30,000 Japanese Americans before the war. Little Tokyo was rechristened Bronzeville and Black-owned businesses replaced shuttered Japanese Americans establishments. The deserted Kawafuku restaurant reopened as Shepp’s Playhouse, one of many night clubs that hosted the likes of Coleman Hawkins, Herb Jeffries from the Duke Ellington band, and T-Bone Walker.

As the Black community began to thrive, overcrowding and governmental neglect led to an increase in crime and public health concerns in Bronzeville. The neighborhood was treated as a blight by the city of Los Angeles, with officials regularly issuing evictions and abatement notices in response to living conditions they deemed substandard. This was the cruel irony of the structural racism Black residents faced in wartime Los Angeles: they were punished for the inevitable outcomes of overcrowding that the city’s restrictive housing covenants had precipitated.

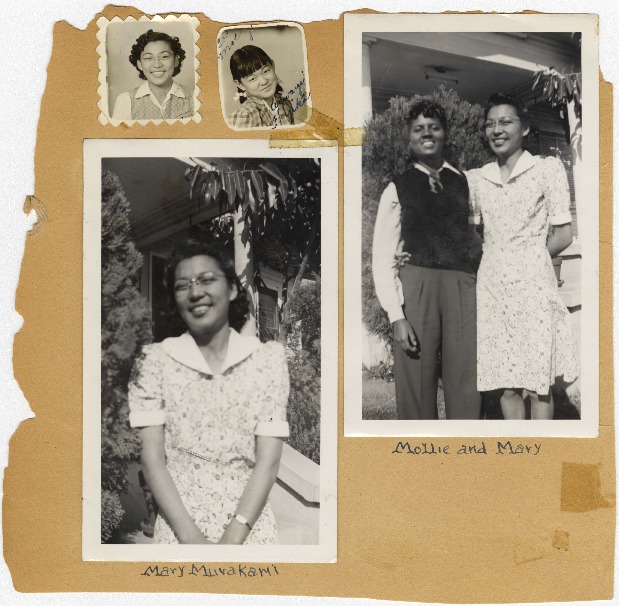

Even as African Americans were struggling for their own basic rights in Los Angeles, individual stories document an incredible showing of support for incarcerated Japanese Americans. Takashi Hoshizaki, for example, recalled the shock and joy he felt at discovering his Black neighbors, the Marshalls, had traveled all the way to the Pomona detention facility in order to bring apple pie and ice cream to his family. Boyle Heights resident Mollie Wilson had a number of Japanese American friends in pre-War Los Angeles. Throughout their incarceration, she kept in regular contact with several of them, sending morale-boosting letters, cards, pictures, and gifts.

African Americans expressed support for Japanese Americans in the public sphere too. Scholar Greg Robinson writes about Hugh McBeth, a Los Angeles-based Black attorney and the leader of California’s Race Relations Commission. McBeth was an outspoken defender of Japanese Americans during the war. In speeches, lobbying, investigatory reports, and lawsuits, he challenged official discrimination,” and argued that “race-based confinement constituted unconstitutional racial discrimination.”

A November 1943 article in the progressive Black newspaper, the California Eagle, called the “persecution of the Japanese-American minority…one of the disgraceful aspects of the nation’s conduct of the People’s War.” In a showing of support, they discontinued use of the racial slur, “Jap,” even though mainstream news outlets would continue using it for years to come.

As Scott Kurashige explains in The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles, “Throughout the following year, California Eagle columnist Rev. Hamilton T. Boswell devoted considerable effort to educating its readers about the problems confronting Japanese Americans and encouraging Blacks to develop greater cooperative bonds with other communities of color,” and condemning “the undemocratic evacuation of Japanese Americans” as the “greatest disgrace of Democracy since slavery” (165).

After the war, Japanese Americans who returned to Los Angeles rightfully wanted to reclaim their homes and businesses, but they found a profoundly different community than the one they’d left behind. With their neighborhood brimming with new residents, many ended up crowded into temporary housing units. The California Eagle argued that Japanese Americans should be permitted to reclaim their former homes and encouraged its readers to stand in solidarity with those returning from incarceration. Even so, tensions–sometimes directly provoked by white media and politicians–rose to the surface, but so too did new opportunities for interethnic alliance.

As Kurashige argues, “Prominent white politicians and media outlets predicted violent turf battles between Black and Japanese Americans would erupt. Black and Japanese American activists, by contrast, envisioned a new level of interethnic political cooperation developing from heightened interaction between their communities” (2).

Regardless of the many instances of Black and Japanese American alliance during and after World War II, some wartime tensions persisted long after the war itself had ended. This strife was not unique to Los Angeles. Even John Okada called attention to it in his classic novel No-No Boy, set in post-war Seattle:

“He walked gingerly among the Negroes, of whom there had been only a few at one time and of whom there seemed to be nothing but now. They were smoking and shouting and cussing and carousing and the sidewalk was slimy with their spittle.”

‘Go back to Tokyo, boy.’

Persecution in the drawl of the persecuted.”

In some instances, overt anti-Black sentiments rose to the surface in the decades following World War II. Pediatrician and activist Dr. Clifford Iwao Uyeda emerged as a vocal critic of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1961, he issued racist missives contending that Japanese Americans had overcome far greater discrimination than their Black peers, but without sharing their “excessive crime rate.” He added that “the re-education of the minority groups themselves towards better citizenship” was more important than legislation supporting equality. Employing the same racist line of thinking, Hokubei Mainichi editor Howard Imazeki challenged African Americans to “improve their own communities before asking for equal rights.”

Countering these anti-Black narratives were numerous stories of Japanese Americans supporting Black rights and standing up to racism. There was Joe Ishikawa who worked with African Americans to desegregate swimming pools in post-War Lincoln, Nebraska. And Yuri Kochiyama, who famously allied herself with the Civil Rights Movement and Black nationalists like the Republic of New Africa. After meeting Malcolm X at a courthouse in 1963, they forged a friendship that would last until his death. Just 16 months after their first meeting, Yuri witnessed Malcolm X’s assassination and rushed to his side in his dying moments, a tragic moment poignantly captured in this Time Life photograph.

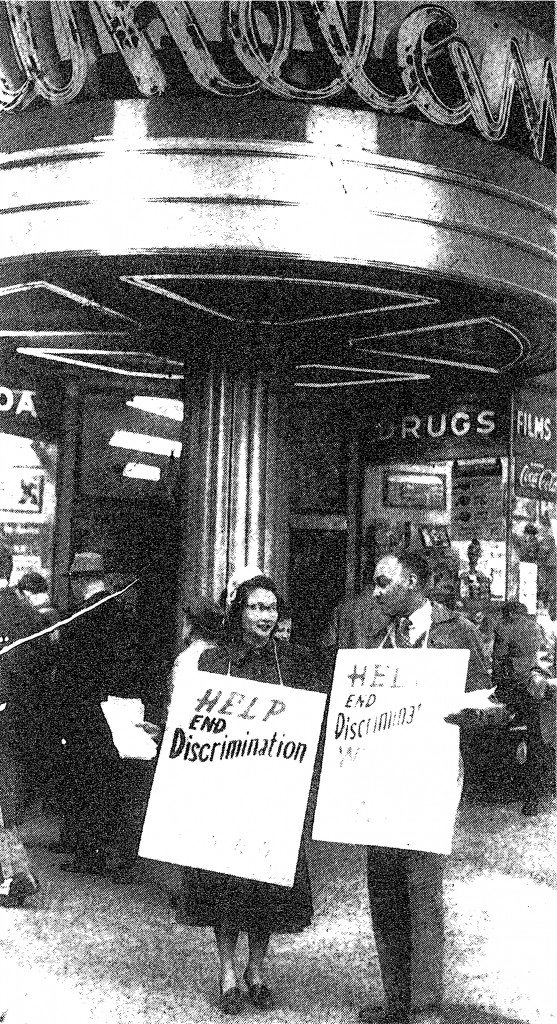

Another Japanese American woman, Ina Sugihara, became a civil rights organizer while living in New York. In 1943, she helped to found the Congress of Racial Equity (CORE) and created multiracial coalitions through the JACL and the watchdog agency, the Fair Employment Practices Committee. In 1945, she wrote presciently about the importance of multiracial alliances to fight discrimination, saying: “The fate of each minority depends upon the extent of justice given all other groups.”

Despite her commitment to coaltion-building, anti-Black attitudes impacted Sugihara on a personal level. After her 1955 marriage to Willis Jones, an African American man, she was increasingly marginalized within her own community. As Greg Robinson notes, Sugihara and her husband were “made to feel uncomfortable at community events and she largely withdrew from Japanese American activities.”

Anti-Black sentiments persisted in the Japanese American community despite the history of support from and collaboration with African Americans, but those sentiments rarely went unchallenged. The monthly newsletter Gidra, considered by many to be the voice of the Asian American movement, became a strong anti-racist agent and proponent of multiracial coalition-building. In the June-July 1970 issue, Mickey Nozawa condemned the Japanese American Citizens League community center in Long Beach for an incident in which a mixed group of Japanese American, Black, and Chicano youth were denied entry and all future access to the community center facilities. Nozawa wrote, “How can we ever bring about meaningful changes in this blatantly racist nation if we allow racism to be practiced within our own community?”

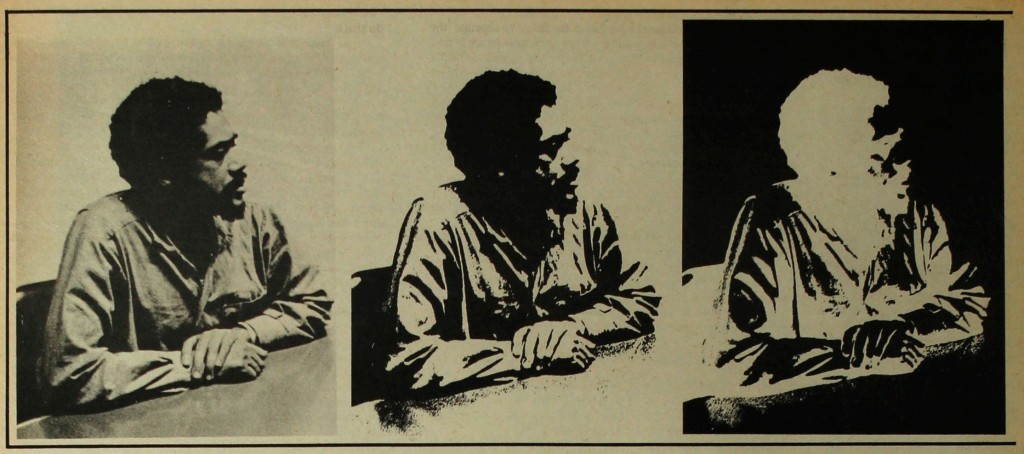

The same issue of Gidra included an exclusive interview with Bobby Seale, the National Chairman of the Black Panther Party who was being held at the San Francisco County Jail while awaiting extradition to Connecticut. In a lengthy discussion of the aims of the Black Panther Party, Seale touched upon the fact that resistance to shared oppressions should be seen as a foundation for multiracial alliance:

“In general, I see the struggle moving with all the people and not just with Black people alone. I see the Asian people playing a very significant part in solving the problems of their own community in coalition, unity, and alliance with Black people because the problems are basically the same as they are for Brown, Red, and poor White Americans–the basic problem of poverty and oppression that we are all subjected to.”

Despite this legacy of allegiance, anti-Blackness lingered in some Japanese American communities, no doubt stoked by racist narratives perpetuated by American white supremacy and the model minority myth. As Kim Tran wrote in a recent Everyday Feminism article, “The Black community frequently serves as our negative definition–the people we don’t want to be…White supremacy fed us anti-Black racism and many of us believe it out of fear–and hope.”

There are signs that these currents of racism might be ebbing while Asian American-Black coalition-building is on the rise. Asian American groups like #Asians4BlackLives stand in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. Meanwhile, Asian American students are speaking out against anti-Black policies on their college campuses. Rather then letting this be a gradual, generational shift, writers like Tran have proposed ways that Asian Americans can broach the thorny subject of anti-Black racism within their own families.

At Densho, we’re working with other Seattle-area groups, including the Northwest African American Museum, to launch new collaborations to develop social justice and racial equity curriculum. Densho Executive Director Tom Ikeda said, “As we begin to build coalitions with other communities of color, it’s important that we take a hard look at the history of anti-Black sentiment within the Japanese American community. In line with Densho’s mission to ‘promote equal justice for all’ and in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, we must speak out against the racist attitudes that have festered in our own community.”

With the work of pioneers like Yuri Kochimaya, Ina Sugihara, Bobby Seale, and the writers of Gidra and the California Eagle to turn to, we have a strong precedent of multiracial coalition-building to draw upon. This post is the first step in what we hope will be an ongoing conversation.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications Manager, with scholarly contributions from Brian Niiya and Greg Robinson.

[Header photos: Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron is shown at front of an abandoned Shinto shrine in Little Tokyo/Bronzeville. Shown with the mayor are a Bronzeville family (unnamed by the source), Dr. George M. Uhl, city health officer, and Nicola Giulli, chairman of the City Housing Authority. Photo dated May 25, 1944. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library.]