May 11, 2017

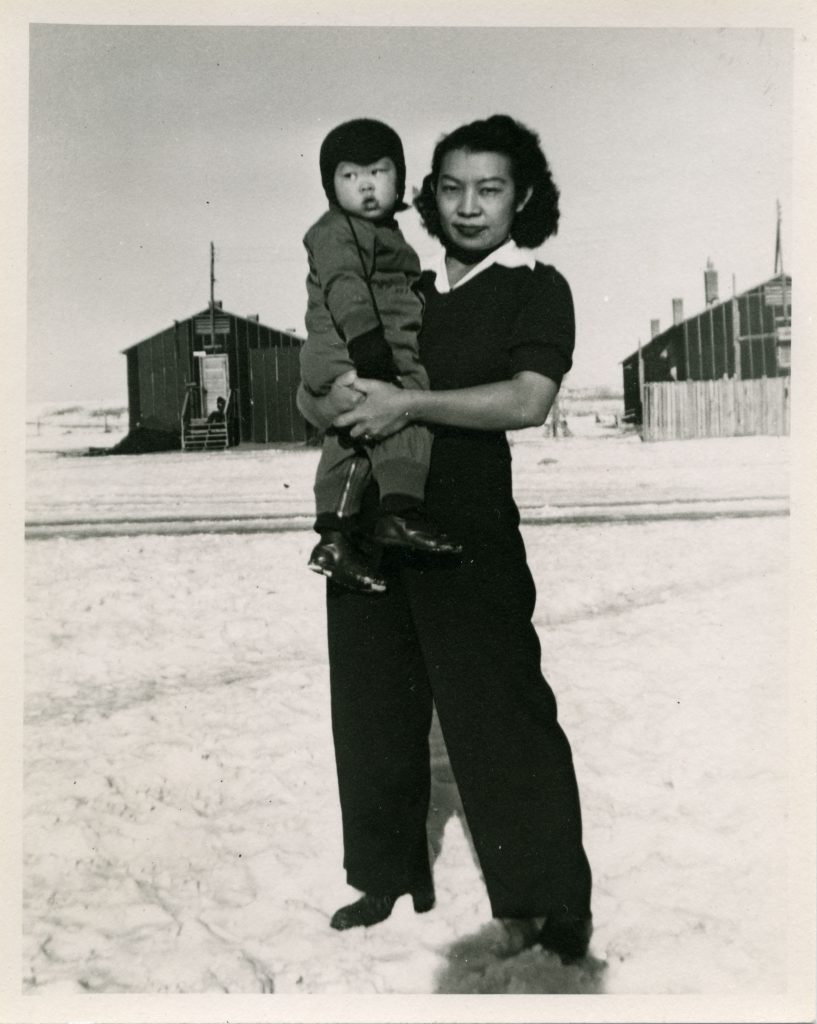

The events of World War II—from forced removal and incarceration on the mainland to martial law and the separation of internee families on Hawai’i—was difficult for all Japanese Americans, regardless of age, gender or family status. But mothers faced unique challenges that compounded many of those hardships.

Within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI began arresting the mostly Issei men flagged as security threats during the decade of government surveillance that preceded the war. Over 1,200 businessmen, Buddhist priests, Japanese language school teachers, and other community leaders were taken into custody within the first 48 hours. That number would eventually swell to more than 5,500.

Many of these men left behind wives and children. They were picked up without warrants or charges, and families sometimes waited weeks to find out where they were being detained—in many cases learning that they had already been sent to Department of Justice internment camps like Santa Fe or Missoula. In Hawai’i, mothers faced a tough decision: remain in the territory and attempt to eke out a living under the restrictions of martial law, or submit to “voluntary” incarceration on the mainland so that they could be reunited with their spouse.

Women who had the misfortune of losing their husband to the Enemy Alien Control Program, as it came to be known, suddenly found themselves alone in a hostile environment, bearing the full responsibility for supporting their children financially and emotionally. Mako Nakagawa remembered her mother’s struggles to keep the family afloat after her father’s arrest: “My mom, she paid a high price. I think most of the Issei women paid just a dear, dear price with getting no recognition for the kind of pain that they went through. And not only was she in dire straits [because the money was frozen], she had four little girls. The oldest one was just eleven and the youngest one was just a baby yet.”

Even for mothers who were “lucky” enough to keep their families intact, preparations for removal—packing up belongings, deciding what to keep and what to sell or give away, attempting to minimize interruptions in their children’s educations, not to mention the emotional labor expected of women during family crises—proved difficult.

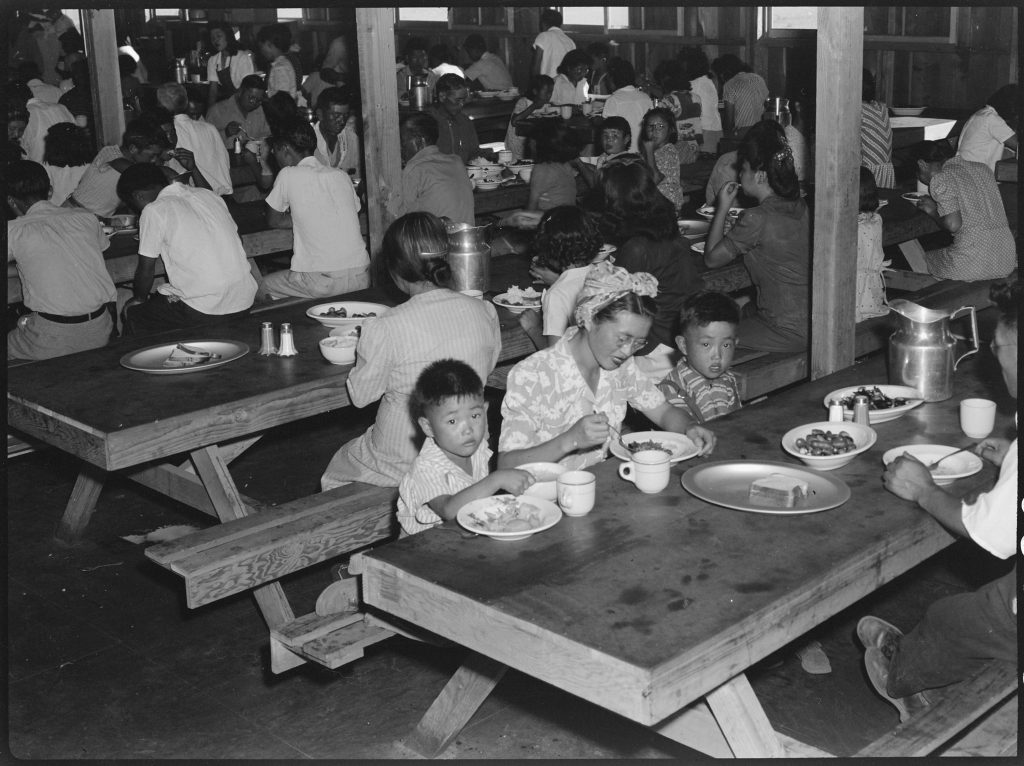

After arriving in camp, mothers encountered a whole new set of issues. Everyday chores like laundry, housekeeping, bathing and feeding their children, and other examples of typical “women’s work” became harder in the crowded, subpar camp facilities. Women who were incarcerated in the same facility as their extended family appreciated the benefit of additional helping hands, but others who were more isolated reported feeling overwhelmed by their motherly duties.

At many of the camps men took seasonal jobs as farm laborers or factory workers that required them to be gone for months at a time, leaving their wives to take on the primary childcare responsibilities. While this was certainly a valuable means of contributing to the family’s welfare, some mothers resented the burdens imposed by these absences.

Ada Otera Endo, for one, recalled, “I felt the inequity of the whole thing. A woman is left, is stuck with everything. A man is free as a bird, and they don’t share with the care of the children or worry about their future or anything like that. They just go their own way. I felt that way.”

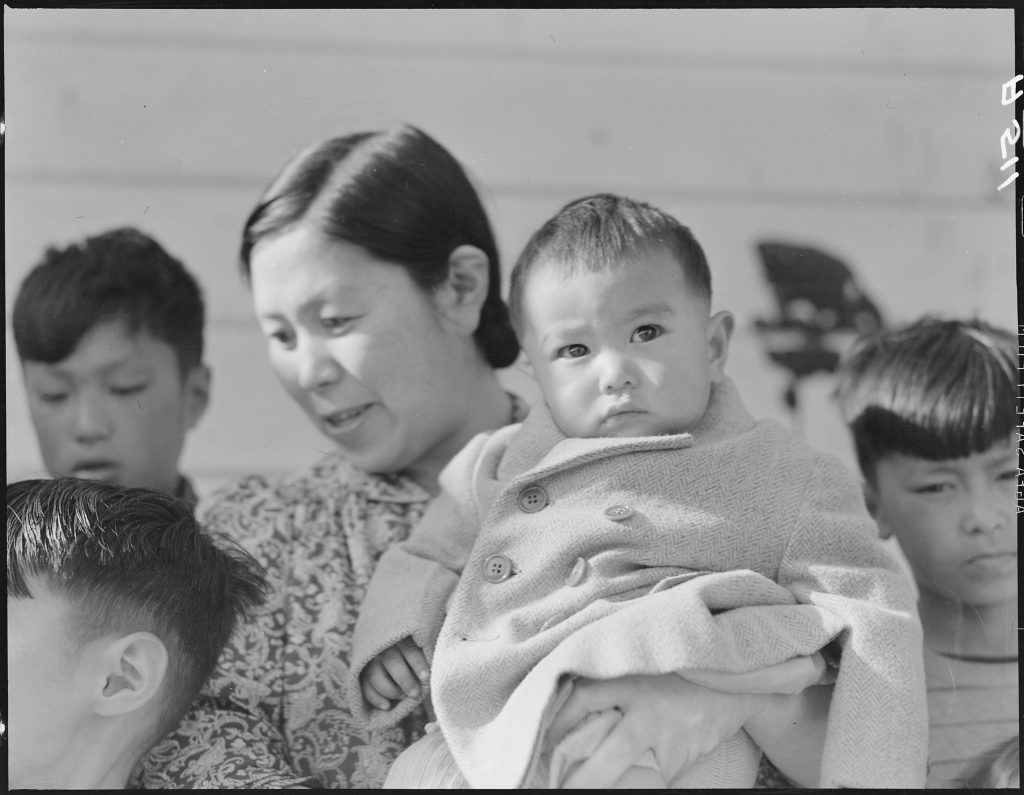

Pregnancy and childbirth were another challenge—and one that, with an uncertain future and limited access to reliable contraception, many women did not face entirely willingly. In an atmosphere so overtly hostile that Oklahoma Senator Jed Johnson in 1945 proposed a bill to forcibly sterilize Japanese American women, it’s no wonder that many inmates were reluctant to take on the responsibilities (and risks) of motherhood.

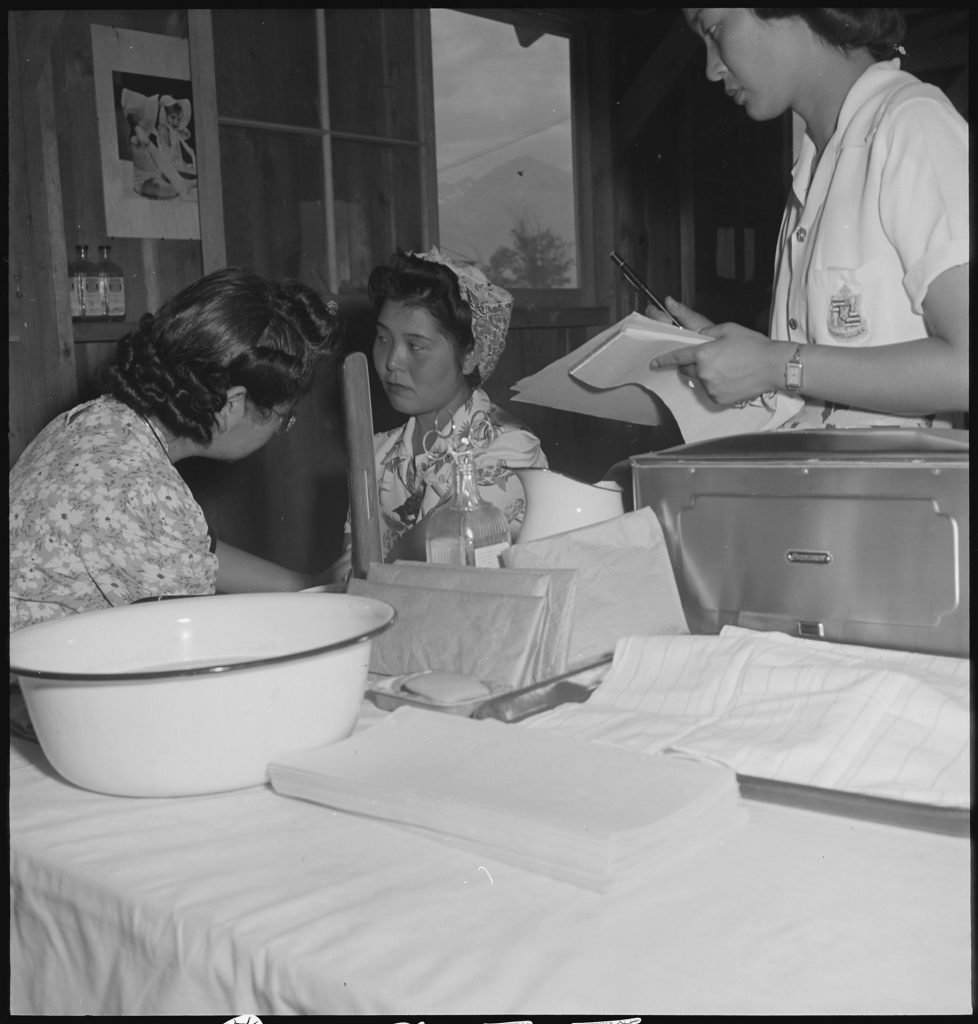

Planned or unplanned, 504 babies were born in the assembly centers and another 5,981 in the ten WRA camps. Most women described their prenatal, delivery and postnatal care as adequate, although complaints about inexperienced or less-than-friendly doctors were not uncommon. Incidents of deaths during childbirth caused by poor conditions in camp hospitals were also known to happen.

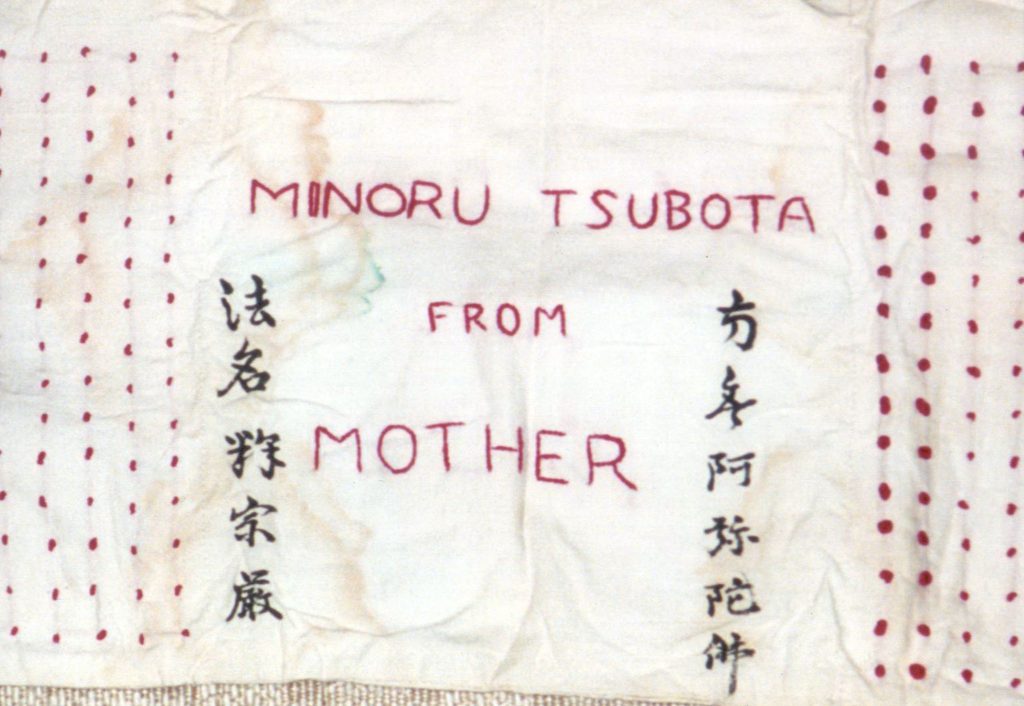

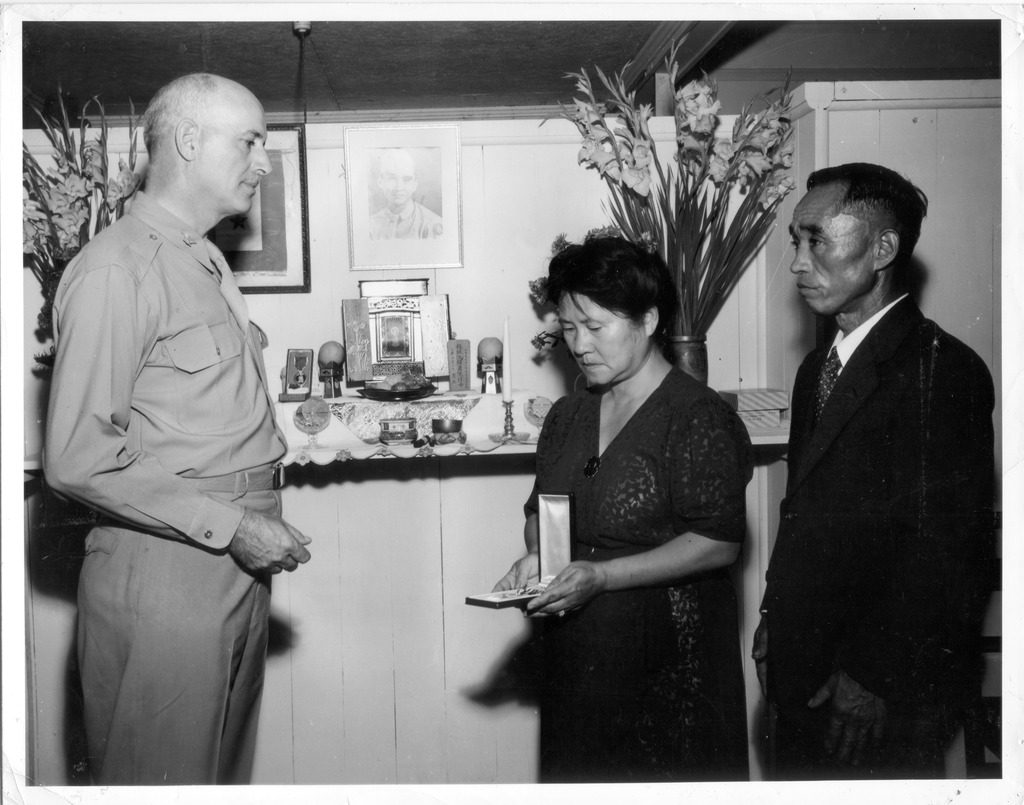

For mothers whose sons had volunteered or been drafted into military service, the constant worry for their sons’ safety was yet another reminder of their precarious situation. The irony of sending their children off to war when they themselves had been labeled dangerous and un-American was not lost.

The racial segregation of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was also seen as an affront, even to women who did not object to their sons’ military service. In a few notable cases, like the Mothers of Topaz, Issei women organized to protest the induction of their sons into segregated units while their families were incarcerated, arguing that the discriminatory nature of the draft violated their Nisei children’s citizenship rights.

As restrictions were eased on exiting the camps and the WRA increasingly pushed a policy of assimilation and resettlement, many Japanese Americans began to relocate to the Midwest and East Coast. Often fathers would leave first to secure housing before sending for the rest of the family, which meant that the task of caring for children and elderly relatives fell to the mothers who stayed behind.

These new homes were often located in areas with small or nonexistent Nikkei populations, as the WRA tried to break up the pre-war communities and steer resettlers toward “Americanization.” In this limited social network, many mothers found themselves raising their children in a foreign place with few friends.

In spite of the myriad challenges and difficult choices they faced during World War II, Japanese American mothers found ways to transcend the harsh conditions that threatened to tear their families apart. This Mother’s Day, we honor their legacy and express our gratitude for the women who carried the Japanese American community through the war years and beyond.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator

Ada Otera Endo quoted by Susan McKay in The Courage Our Stories Tell: The Daily Lives and Maternal Child Health Care of Japanese American Women at Heart Mountain (Powell, Wyoming: Western History Publications, 2002).

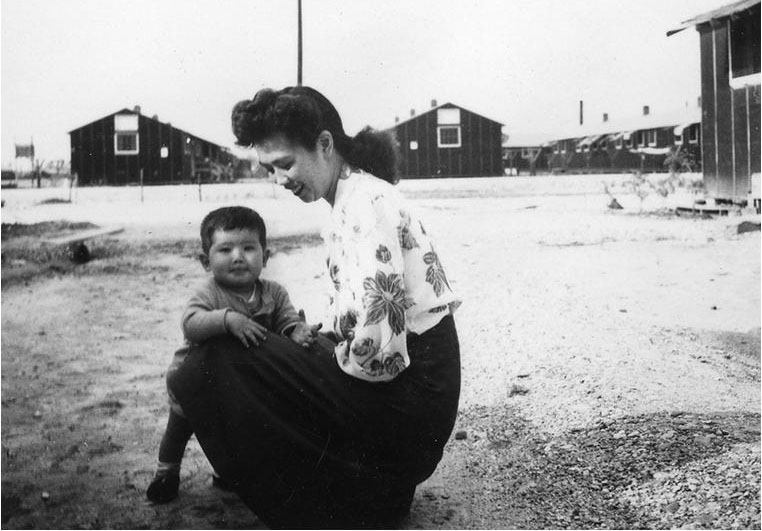

[Header photo: Mother and child in camp. Rohwer, Arkansas c. 1943. Photo courtesy of the Kuroishi Family Collection.]