July 21, 2025

At Densho, it is common to come across scrapbooks that document the variety of memories that make up someone’s life, capturing friendships, personal growth, family milestones, and other moments of joy and celebration. Often, entries about incarceration during WWII appear alongside these mementos, and they serve as a reminder that even in the face of injustice, people continue to live full, complex lives. These scrapbooks serve as a visual testimony that provide further insight into the daily life in the camps.

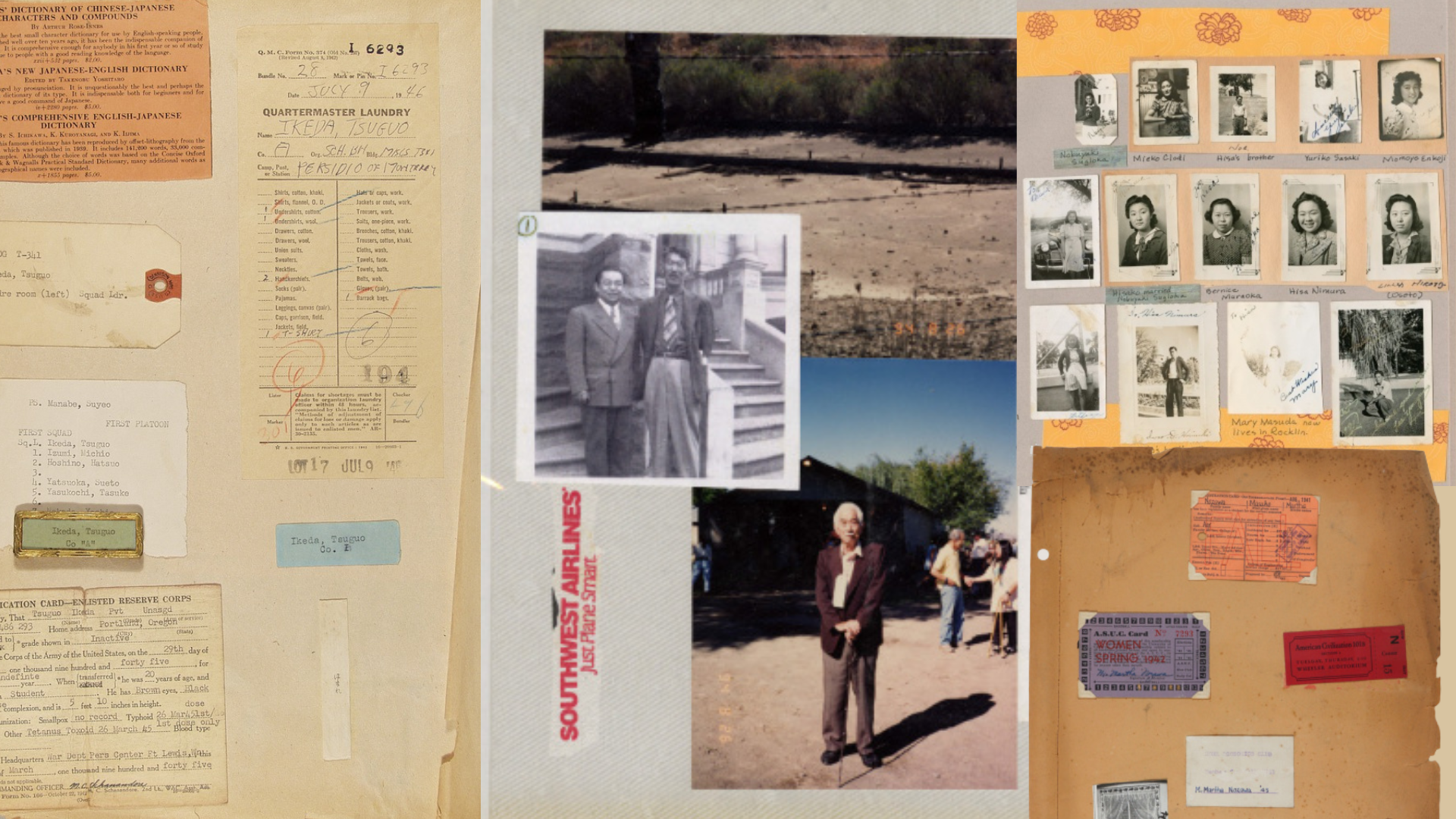

At the start of my internship, I began processing the Tada Family Collection. As part of this collection, I digitized a scrapbook that detailed the life of the Tada family through newspaper clippings, graduation announcements, wedding invitations, and letters between friends. Layered alongside this memorabilia were materials documenting their incarceration at Minidoka. As I scanned each page, I came to understand the scrapbook as not only an act of self-documentation but also historical preservation. In addition, I got to learn how tricky it can be to digitize visual objects that have minimal descriptions or labels.

Scanning Process

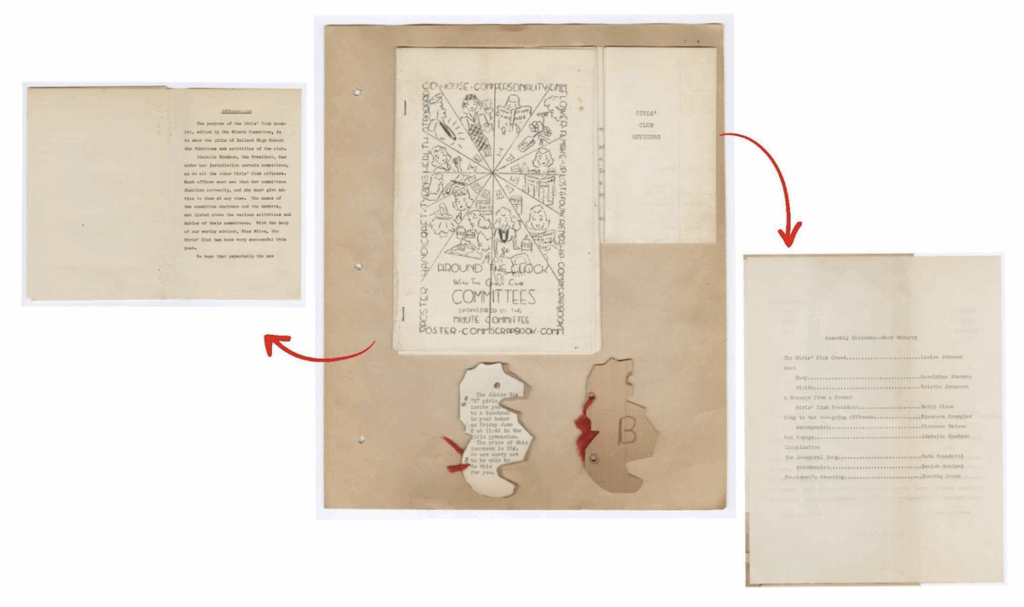

The layered elements of scrapbooks often create many challenges when preparing them for the digital archive. Scanning can prove to be difficult, especially when images overlap, extend past the page, or include three-dimensional objects.

As part of our workflow, we often scan each scrapbook page in multiple segments to fully capture every element of it. Sometimes, that results in merging the scans later on in Photoshop. Sometimes, we have to use different imaging equipment if we aren’t able to use our typical scanner. While archivists value standardization in order to maintain consistency across collections, scrapbooks often resist uniformity. Therefore, our approach to digitizing these materials requires flexibility, creativity, and attention to the smaller details that shape the overall narrative of the scrapbook.

When first interacting with the scrapbook, I carefully turned each page to preserve the original order. This was especially important because, over time, many of the mementos had come loose and were no longer glued to each page. And as I started the scanning process, I began to learn more about the collection.

Masako Tada was a member of the Big “B” Girls Club at Ballard High School, a club for students who maintained good grades and were active on a sports team. For Masako Tada, that sport was tennis. Here’s an example of a page that included several different elements that highlighted her participation in the student organization:

When digitizing items, it’s important to try to maintain the tactile experience of interacting with a scrapbook. While a digital archive greatly increases access to these materials, the lack of physical interaction with a collection can make it more difficult for viewers to fully grasp the texture and depth of the item. To try to mimic the tactile experience of interacting with the object, each element of the page is scanned as though someone was flipping through the scrapbook themselves.

Description Process

During digitization, we focus on making each object easy to search for through descriptions and tags. Since scrapbooks rely heavily on visual elements with limited captioning, it can be difficult to determine the relevance of each item. Oftentimes, a few labeled items or contextual clues help put the pieces together.

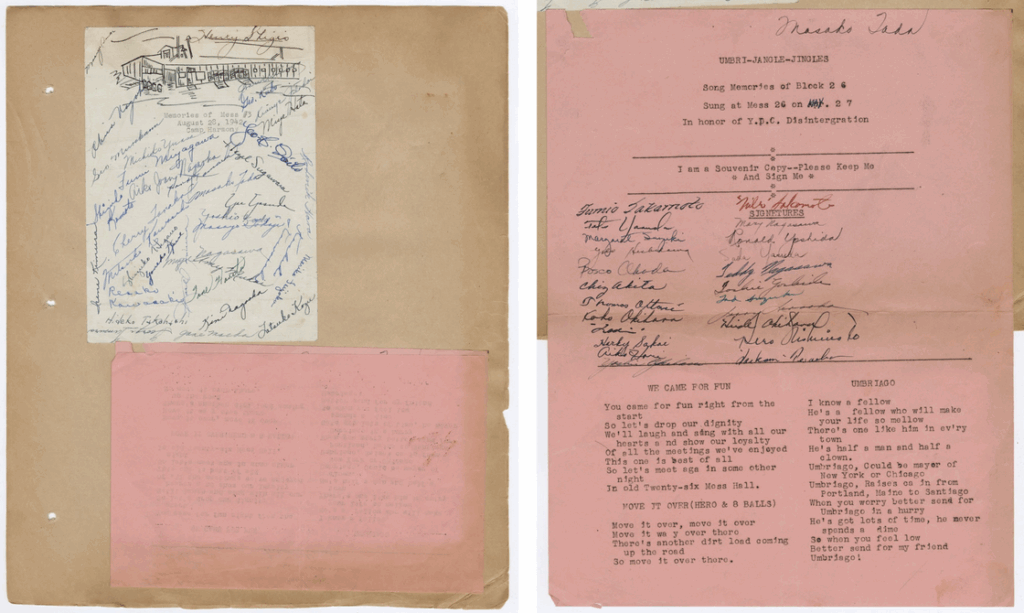

The Tada family was initially incarcerated at the Puyallup Assembly Center—euphemistically called “Camp Harmony”—a temporary camp in Washington. On this page of the scrapbook, there’s a small sheet of paper covered with signatures—a record of the many relationships that the Tada family formed during their brief time there. On the adjacent pink page, the statement “I am a Souvenir Copy–Please Keep Me” is printed at the top, surrounded by additional signatures as well as song lyrics. Together, these pages offer a glimpse into the social life at the temporary camps, documenting the efforts to preserve a sense of community in the face of displacement. Each of these items tell their own story, so we also include them as individual items in the Densho Digital Repository so that we can make it easier for researchers to find these objects, even if they aren’t exploring the scrapbook itself.

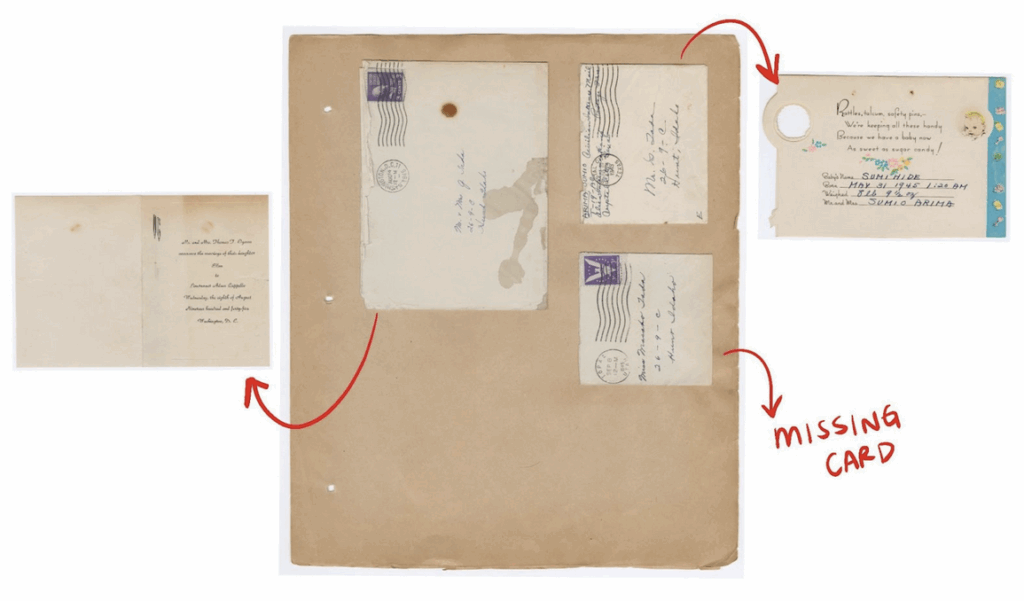

Afterwards, the Tada family was transferred to the Minidoka camp in Idaho. During their incarceration, they received letters that chronicled moments of celebration, including the news of a newborn baby, an upcoming wedding, and warm updates from friends. In order to document these connections that persisted despite the separation due to incarceration, we record the city, camp name, and date for both the sender and the recipient, along with their names. This allows us to build connections between items across the larger collection while making it easier for researchers to trace the relationships between individuals.

From Personal Keepsake to Historical Record

Scrapbooks are a personalized historical record. From birthday cards to pressed flowers, they offer insight into the emotional texture of everyday life. The scrapbooks in our collection were not made with the intention of one day being housed in an archive. Rather, they were deeply personal projects that were crafted to hold memories. Ultimately, these personal stories are part of the larger narratives of history, and they fill in the gaps left by institutions and official records.

—

Micaela Duran is a graduate from the University of Washington’s Master of Library and Information Science program. She holds a BA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Anthropology from Colby College, where she developed a critical understanding of power, identity-making, and collective memory.

Her previous experience in equity-based archival work led her to Densho, where she serves as a Digital Archives Intern in partnership with the University of Washington and the Mellon Foundation. In this role, she is digitizing, processing, and describing collection materials. Through her work, she is committed to ethical stewardship and fostering community-driven approaches to archival preservation.