August 22, 2020

Lane Ryo Hirabayashi was an innovator in the field of Asian American Studies, a historian and storyteller who dedicated his life to deepening public knowledge of Japanese American WWII incarceration, and a mentor to generations of students. In this touching tribute, Densho Content Director (and longtime friend) Brian Niiya describes Lane’s incredible life and impact.

Even though we all knew it was imminent, I was still shocked and saddened to learn of the passing of Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, a good friend, and one of the most important chroniclers of the Japanese American incarceration and its aftermath.

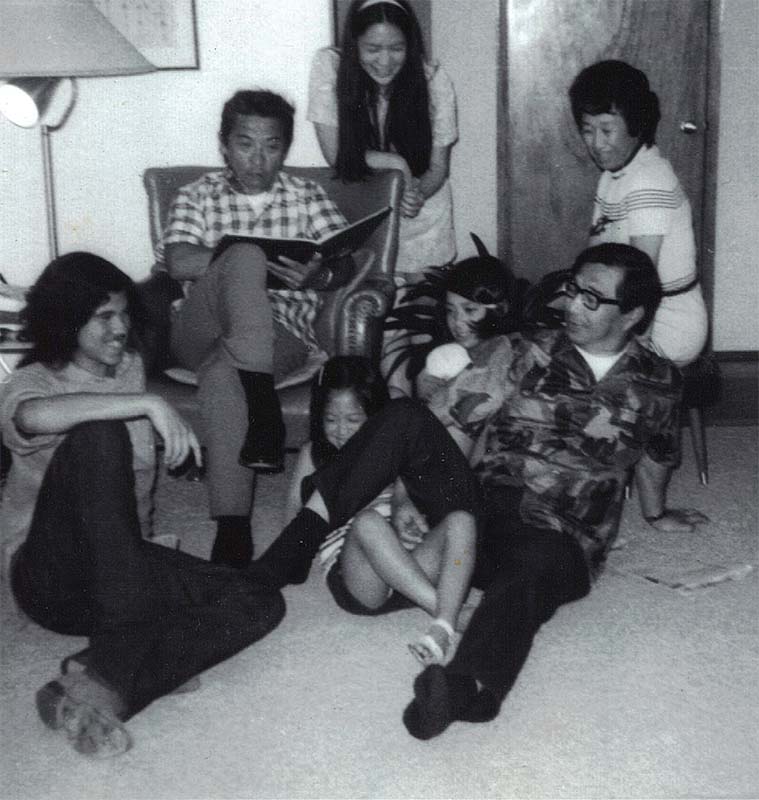

Lane Ryo Hirabayashi was born on October 17, 1952 and grew up mostly in Mill Valley (just north of San Francisco) with his younger sister Jan and his parents James and Joanne after his Nisei father took a faculty position at San Francisco State University. As a teenager, young Lane became caught up the 1960s music scene in the San Francisco Bay Area and became almost famous as a guitar player for the Muskadine Blues Band before his life and career took a different path. After graduating from Cal State Sonoma in 1974, he entered a graduate program in anthropology at UC Berkeley, no doubt influenced by the academic career of his father as well as his uncle, Gordon Hirabayashi.

As with his father Jim (an anthropologist who was a pioneering figure in the fight for ethnic studies at S.F. State) and Gordon (yes, he was that Gordon Hirabayashi), Lane mixed his studies with activism. He was a member of the San Francisco-based Committee Against Nihonmachi Evictions, which fought to preserve housing for Issei elders during the redevelopment process of San Francisco’s Japantown. In the early 1980s, while based in Southern California, he did participant observation research on the formation and early years of the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR) and also did research on the history of the Japanese American community in Gardena, California while volunteering with Gardena Pioneer Project, a social service organization that aided elderly Issei. In the meantime, he did his anthropological fieldwork in Mexico and completed his doctoral dissertation at Berkeley in 1981 (titled “Migration, Mutual Aid, and Association: Mountain Zapotec in Mexico City” and later published as Cultural Capital: Mountain Zapotec Migrant Associations in Mexico City by the University of Arizona Press in 1993), taking a series of lectureships in California upon his graduation before landing a tenure track position at San Francisco State in 1984. From there, he moved on to the University of Colorado at Boulder in 1991, UC Riverside in 2003, then to UCLA in 2006, where he served as the George & Sakaye Aratani Professor of the Japanese American Incarceration, Redress and Community and chaired the Asian American Studies Department. He retired to emeritus status in 2017.

Over the past forty years, Lane has been one of the most prolific and significant scholars of the Japanese American incarceration experience, as well as someone who has engaged with community based organizations to make that experience better known. His work on the incarceration falls into several different areas. One major thread has been his exploration of the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS), a multi-disciplinary research project based at the University of California Berkeley that placed dozens of fieldworkers in the concentration camps in an attempt to study the events as they took place. Controversial then and now, Lane wrote/edited two books and various articles on key Nikkei figures in JERS, Richard S. Nishimoto and Tamie Tsuchiyama, that, among other things, show us the value of JERS-generated research and how, given the right context, they remain useful bodies of data for studying the incarceration.

Another thread of his research focused on government photography of the incarceration and on “resettlement” era, the story of those Japanese Americans who left the concentration camps for areas outside of the West Coast restricted area. His 2009 collaboration with Kenichiro Shimada titled Japanese American Resettlement Through the Lens: Hikaru Carl Iwasaki and the WRA’s Photographic Section, 1943–1945 (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2009), a collection of Nisei WRA photographer Iwasaki’s cheerful images of Japanese American resettlers and an assessment of what such photographs attempted to do at the time and how they might still be useful today. He contributed biographies of Iwasaki and other (white) WRA photographers to the Densho Encyclopedia, that will help future users of these widely available images properly contextualize them. He engaged in additional research on the resettlement in Colorado during his decade plus at the University of Colorado and was working on writing that material up at the time of his passing.

Other threads included one on activism and the redress movement, a topic he wrote about throughout his career, but that culminated in the publication of NCRR: The Grassroots Struggle for Japanese American Redress and Reparations (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press 2018), which he co-edited with leaders of Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress.

He explored the family legacy in various articles as well as in a volume on Gordon that he co-edited with Jim, A Principled Stand: The Story of Gordon Hirabayashi v. United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013). It was one of several collaborations between Jim and Lane, something that they both cherished and that I always envied.

He also wrote a number of pieces on education (including one on education in the concentration camps) and teaching Asian American Studies, some of which focus on teaching specifically about the incarceration. One of my favorite articles that he wrote focuses on the use of Wakako Yamauchi‘s short story “The Sensei” to teach about the incarceration and its aftermath. This insightful essay also introduced me to Wakako’s classic story, which has become a favorite. He was also a strong proponent of using film and video in teaching, and in that capacity, led an effort to preserve and restore Toshi Washizu’s 1983 documentary titled Issei: The First Generation, one of few visual records of the Issei. In another essay, he also introduced me to what has become one of my favorite videos on the incarceration, Michael Toshiyuki Uno’s 1979 documentary Emi.

A perusal of his other publications on his website (though it is not up to date) reveals more: writings on literature, including on seminal Filipino American writer Carlos Bulosan (done in collaboration with Lane’s life partner, Marilyn Alquizola); reviews of many of the major works in Japanese Americans studies over the past four decades; essays on mixed race Japanese Americans that draw on his own experiences; work on international Nikkei communities with Jim; as well as a whole body of scholarship based on his Latin American anthropological work.

He also taught and mentored a couple of generations of students at his various university posts and remained active in various community organizations, including the Center for Japanese American Studies, the Japanese American National Museum, and Densho, among many others.

If there is a common thread in his work, it is one of advancing the study and teaching of Asian American Studies and of the wartime incarceration and its aftermath in particular. A lot of his writing, for instance, is about how to use various types of resources to advance research and teaching. A lot of his work is also collaborative. This also comes into play in his general editorship of the “George and Sakaye Aratani Nikkei in the Americas” book series at the University of Colorado Press that has produced a wide variety of works in various disciplines and has greatly added to our knowledge on the Nikkei experience. I think this emphasis that so strongly encourages the work of others is evidence of a generosity of spirit that I was one of many to benefit from.

I first met Lane around 1987, when I was a very green intern at the Japanese American National Museum. I had just started writing articles in a local vernacular newspaper, and he was the first person (other than my mom!) who noticed and had nice things to say about them, something that was very meaningful to me. He remained a mentor, sounding board and good friend ever since, someone I could always call on for advice on arcane aspects of Japanese American history, the politics of academia and of the JA community, or just life in general. He and Marilyn were my roommates for a summer in LA in the 90s, and I recall fondly a couple of visits to see them—along with a persistent bear from the nearby mountains—in Boulder, Colorado. I moved back to LA in 2017, about the time he retired from UCLA, and I found him to be as happy as I’d seen him (something that is not uncommon among recently retired academics), free to pursue the research and writing he enjoyed while being freed from the not-so-enjoyable administrative and political aspects of the job. He talked excitedly about things he wanted to do and about spending time with his grandchildren, showing a side of him that I had never seen before.

At Densho, Lane has been a key advisor on the various iterations of the Densho Encyclopedia from the beginning and has also contributed a number of articles to it. Though already sick from the cancer that would kill him, he agreed to be an advisor on its most recent California Civil Liberties Public Education Program grant. Over the past few months, I got the sense that he was trying to tie up loose ends, one of which was a final article for the encyclopedia. It is on the Center for Japanese American Studies in San Francisco, an organization that played a key role in changing attitudes in the community towards its history, incarceration, and redress, but that had been largely forgotten. As a piece that combines the personal and the historical, preserves a story that might otherwise be forgotten, and is about an organization that promoted the study and teaching of Japanese American history, it is a fitting last contribution from Lane.

It is sad that he is gone so young, with so much more that he had hoped to do left undone. It is a great loss to the Japanese American community that we will never see what he had planned for us over the next couple of decades. But the tremendous amount he did accomplish in his forty years of writing and teaching will ensure that his contributions to our knowledge of the incarceration and its aftermath will never be forgotten.

—

By Densho Content Director Brian Niiya

[Header photo: Portrait of Lane Ryo Hirabayashi. Photo by Jake Fabricius, courtesy of Zócalo Public Square.]