April 13, 2021

Earlier this year, Densho artist-in-residence Lauren Iida sat down with Erin Shigaki — a longtime Densho friend, designer, and artist — for a conversation about how their art is influenced by their shared lineage as descendents of WWII incarceration. Since they couldn’t safely sit in the same room together due to COVID, this interview was conducted via Zoom with creative workarounds engineered by Common AREA Maintenance, a beloved Seattle art space. Lauren’s work is currently featured in their storefront as part of their Second Avenue Sign Project, and is safely viewable from the street. If you’re in the Seattle area, we encourage you to stop by and check it out (2125 2nd Ave. in Belltown)!

This interview has been condensed to highlight the artists’ conversation about WWII incarceration history and its legacies. For more on Lauren’s practice and work in Cambodia, watch the full interview:

Erin: How is your spirit today?

Lauren: Good, I’m feeling pretty good. It’s a crazy time. It’s been a crazy year, but I’m really happy to be here in Seattle. And I got to see a few people social distanced, and it’s nice to reconnect with my hometown, and see the rain, smell the ocean a little bit. So, I feel pretty good today, yeah.

Erin: Good. Yeah, I think it’s been a pretty challenging year for everybody, but I was wondering if this pandemic, racial uprising, election year has brought you any unexpected gifts?

Lauren: Yeah, it has actually. The main thing is that I have had more time to make my own art, which has been really great for me, personally. Normally, before COVID, I would be guiding contemporary art tours, working with artists in Cambodia, like, more at a faster pace. And doing lots of other things, all the time. Traveling back and forth between Cambodia and Seattle. But I’ve actually been in Cambodia for the entire pandemic, until about a week ago. Which has just given me a huge amount of time to work on my own projects for the first time in quite a while. So yeah, that has been real good.

Erin: Awesome. So, I wonder if you could just talk a little bit about your creative and artistic beginnings, for those of us who don’t know you very well.

Lauren: Okay. I have been drawing and painting and making art since I can remember. As a child, I was always making art. I grew up in Seattle, I’m born and raised in Seattle, and I’m a graduate of Cornish College of the Arts. I graduated in 2014. And for the last 12 years, almost 13 years, I’ve been back and forth between Seattle and Cambodia, about half and half. Sometimes I’d spend a year here. Sometimes I would spend a month here, and go back for a couple years. So back and forth between Seattle and Cambodia. Those have been my two homes. I make art in both places, and I’m primarily a cut-paper artist. So I do very intricate, highly detailed, very fragile smaller works for exhibition, and also larger scale installation. I cut everything with a scalpel, with an x-acto knife.

Erin: Something that we both do is work around the Japanese American incarceration that happened during World War II. I have a few questions about that matter. The first is, when did you first learn about that history?

Lauren: I sort of had the knowledge that my family had been through that experience, as a childhood thing. Although, I don’t feel like it was really explicitly talked about too much in my family. But as an adult, I became interested in learning about the history on my own, and particularly relating to my art. Because I found the historical photos from that time really profound. And because of Densho, there’s just a fantastic archive of photos from that time. And also my grandmother’s older sister, who I call my Grandma Clara. She also has always been interested in photography, and so she’s kept extensive photo albums from like the first photo of my great-grandfather in America around 1900, until now. All the way through camp and everything. So, yeah, I just found those photos to be really interesting. But, the history in my family was not really talked about very much at all.

Erin: You’re so lucky to have an album full of images from immigration time! But then, especially from camp, right? Since cameras were supposedly not allowed, or at least they weren’t in the beginning. I think that’s really cool. What did you learn in subsequent research or discussions with your relatives about how the incarceration experience impacted them?

Lauren: Well, what I observed was that the — I found myself not knowing anything about my Japanese heritage, at all. My father is Japanese. My mother’s not, so I’m biracial, but I found that I actually had no information about anything having to do with Japanese traditional culture. Maybe a few food things, a few foods kind of made it through. But, no language and no other cultural traditions at all made it down to me. So, that was kind of strange. As an adult, I realized that that was the case, and so I started investigating more on my own. What I inferred from that realization of not being in touch with the traditions of my Japanese heritage was that, probably — I mean, I figured that after camp, my grandmother would have been very embarrassed and very shy and not wanted other people to know that she was Japanese.

I feel like they felt shame about that. And I think that was mentioned to me at some point in my childhood, but I’m not really sure. All I know is that after the war they tried to rebuild their lives in Washington state, in Seattle. And that seems to be when most of the traditional aspects of how they lived disappeared. Yeah, so my father also was not raised with those Japanese traditions, either, or language or anything. So, I think that probably because of the shame of being incarcerated for being Japanese, during the war, they probably tried really hard to hide the fact that they were Japanese, or at least not outwardly celebrate the Japanese parts of their heritage.

Erin: Yeah, kind of a sad but really true part about surviving is assimilating, or an idea of assimilation. But, so, now you are embracing this history in some of your work. And I was wondering if you could talk about that.

Lauren: I will also say that my grandmother’s older sister Clara has been a really important resource for me, to learn about what happened to our family, and how life was before the war, and how she felt about it. So, she was interviewed by Densho in 2013, 2014. And she lets me use the photos, and she’s still alive in West Seattle. She’s 101 now. And so she’s been a really important resource. I can ask her, or I could before ask her direct questions and she would give me amazingly detailed information that she remembered.

Erin: Could you tell us a bit about your work that you’re making about the Japanese American incarceration in the States?

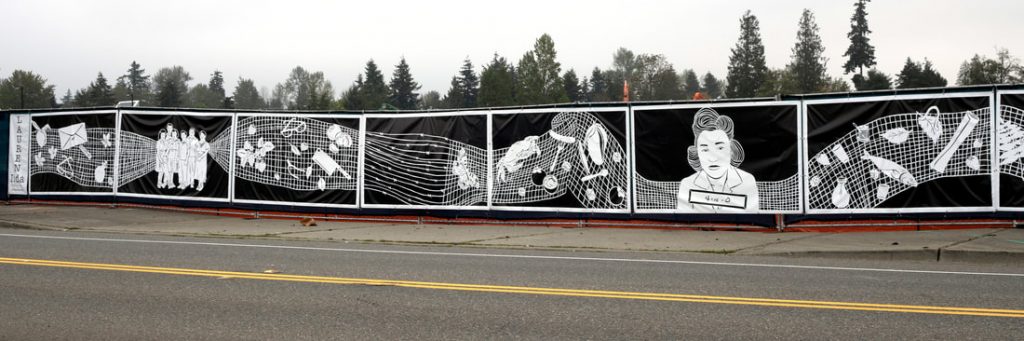

Lauren: Yes. So, a very large mural — a 120 foot long mural just went up in Federal Way a few months ago at the Federal Way Sound Transit Center, which is under construction right now. It is a vinyl-printed reproduction of 12 panels that I made from hand-cut paper in my studio in Cambodia. And then digitally sent them over, and they were printed here. Because of COVID, I couldn’t physically be here to paint them by hand, so that’s what we had to do. That piece incorporates “The Memory Net” with symbolic objects from myself and also from Japanese incarceration — from Lawrence Matsuda’s book, My Name is Not Viola; from my own family’s stories and photos; and from Densho. And then, I put a family portrait from before the war of my grandmother, her older sister, they’re two brothers, and my great-grandparents at their farm in Rockland, California. And they’re all kind of connected by “Memory Net,” with “Memory Net” objects. And there’s a photo, or there’s a part of that mural that is my grandmother’s older sister, Grandma Clara, with her ID numbers from inside Tule Lake Concentration Camp, etc. I also asked a few people who I knew, or just generally asked on Facebook and asked my community for objects relating to the immigrant and refugee experience in America. So, there’s a Hmong baby carrier in there. There are some Cambodian American symbolic objects that people suggested to me as well. So, the whole piece is like a very long Memory Net with symbolic objects trapped in it. And then some portraits of my family members.

Erin: Yeah, it’s gorgeous. If you’re comfortable talking about it, that’s another thing that you and I have in common — we’ve both had public artwork about the incarceration defaced. And I wonder if you had any thoughts to share on what happened with that, and sort of how that affected you?

Lauren: Yeah, as soon as the slashing of my mural panels happened, I thought about what happened to your work immediately and researched more about what happened to your work at Bellevue Community College. What happened to mine was basically somebody took a box cutter and slashed through many parts of the mural, mostly on faces of people in my mural. And also through faces depicting, other murals nearby my mural by other POC artists depicting Black faces, as well. And so, at first Sound Transit said, “Oh, is that an act of racism? I don’t know.” They repaired it. They taped things back together. They printed some panels that couldn’t be saved. And then it immediately happened again. And so, then Sound Transit came out with a statement that said they believed it was an act of racism, and the press wrote some articles about it.

I was in Cambodia still, at that time. So this is the most important, most large-scale piece of public art that has ever come to fruition in my life and it was really, really devastating for me to go through that experience of feeling personally attacked in a racist way. A couple times. Watching your art get defaced — I didn’t really think about it before. I didn’t think how much that would hurt, but it was pretty bad. It was pretty profound. It made me very angry and very sad. So, right now, actually, I’m working on repairing or renovating the panel using the ancient art of repairing broken pottery with fine metals, like gold, which is also Japanese. I’m taking gold paint and gold wire and sewing it back together across the whole slash mark. The one panel that was really badly damaged that they had to reprint. So, I’m repairing it with gold and then it’ll be like an art piece. And Sound Transit is gonna let me put it up with a statement, as well.

Erin: Oh, I love that. I love reclaiming that kind of situation, which we did at Bellevue College as well. Yeah. It’s interesting. It’s the intergenerational trauma that really bubbles up, especially when the defacement is about our history, right? It’s pretty intense. So, what other projects are you working on right now, public-art-wise or other, in the Seattle area or the States?

Lauren: A lot. There’s the Washington State Convention Center addition garage door, all the public art that I’m making for these different projects have to do with World War II and the Japanese during World War II, or some part of the history before or after. After Black Lives Matter started, I made a commitment to myself that I would continue to make work about that topic for public art in Seattle and not really anything else for a while. So, let’s see. There’s the Washington state Convention Center garage door. That’s cut from metal from my paper-cut design. There is Common Area Maintenance. There is going to be an illuminated sign out the front here, and maybe a window display. There’s a project for Sound Transit in ceramic tile mosaic. They’re like these five elevated panels that go along the bike trail to the new Sound Transit Center in Redmond. That will be in the future, but working on it now. There is another mural project that hasn’t been announced yet in downtown Seattle. And a project about, actually, specifically about the Japanese American contribution to agriculture in a mixed-use zone in Bellevue that I’m working on right now as well. Incorporating the words from the poet, Lawrence Matsuda, into my work as well.

Erin: Can you tell us about the piece that we are looking at, that’s right behind you?

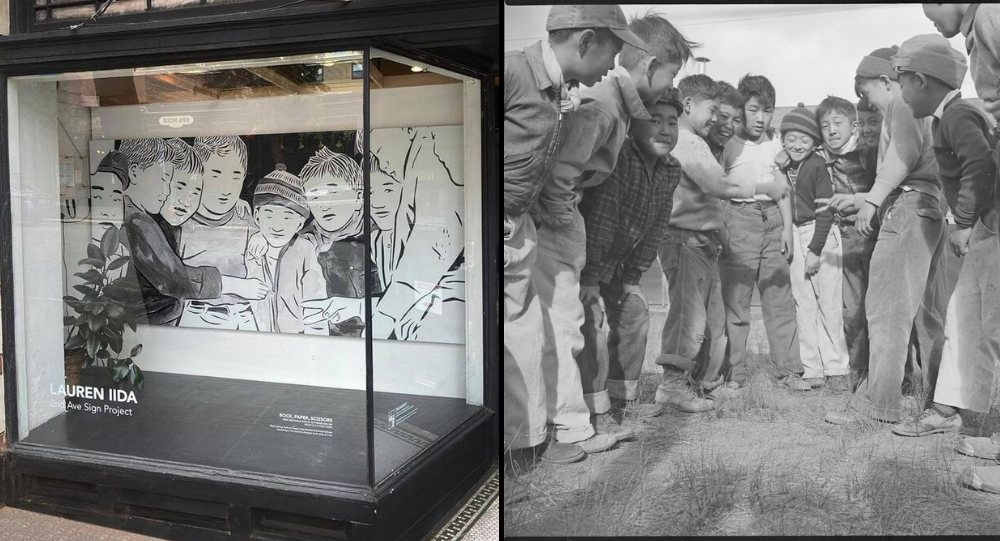

Lauren: Yeah, this piece is called “Rock, Paper, Scissors” and it is derived from a photo I found in the Densho archives of some boys in one of the camps — I’m not sure which one — playing rock, paper, scissors.

And the photo really struck me because I remember a story that Grandma Clara told me about how, when the Japanese were moved into the camps, they suffered in many, many ways but one of the things that was kind of an unexpected positive surprise for her, and she saw in other young people, was that suddenly Japanese families who may have been more isolated, like in rural areas before, suddenly had a lot of other people around, and a lot of other kids to play with. So they started like rec centers and sports teams and schools. And they ran in packs around, and it destabilized the family structure, which probably was not positive in many ways. But it also offered a lot of socialization and fun times for Grandma Clara, which she remembered fondly.

So, the kids playing in this photo really reminded me of her telling me that. And then also I use chance, or the element of chance a lot. The idea that everything in life could be changed at the drop of a hat, or that there’s an element of unpredictability in life, in general. Like the Japanese incarceration, we saw, just one day, you know, their freedoms were taken away and they were moved out of their homes and they had nothing left. And also a lot of people that I am close with in Cambodia are Khmer Rouge survivors, or children of Khmer Rouge survivors. And their lives were completely destroyed at the drop of a hat, as well. So, one of the symbolic objects I use a lot in my work — in “The Memory Net” and other pieces — is dice to symbolize that element of chance in everything we do. And I thought rock, paper, scissors was also kind of a symbol for that.

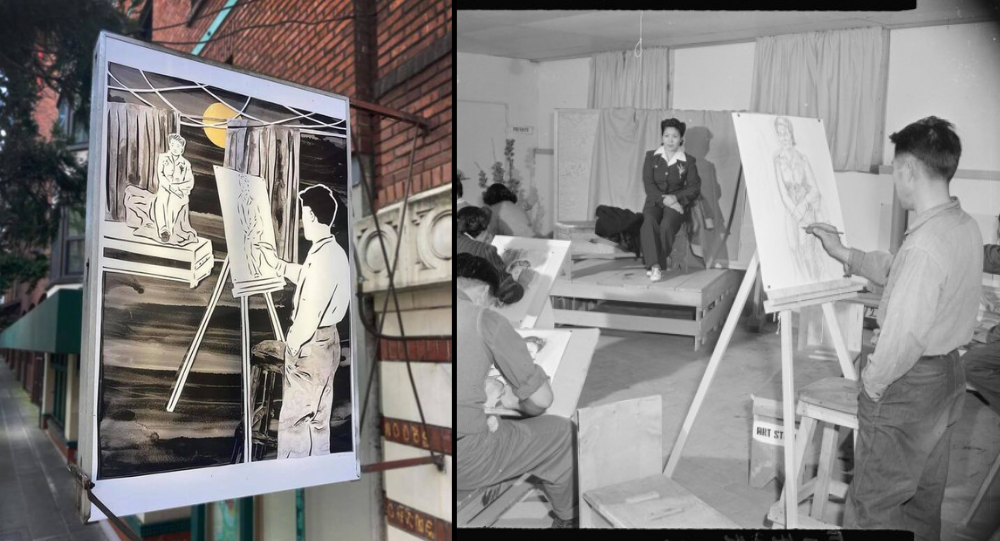

The piece that I made for the sign project for Common Area Maintenance is called “The Artist.” And it was one of the most striking photos I found in my research on the Densho archives as well. I believe it’s from Tule Lake, where my family was incarcerated. It’s a man who is attending a life drawing session inside the prison. And he’s just sketching a woman who’s sitting on a platform, as a hobby. And I thought that was so fascinating that I noticed through many many photos that I find from all the different camps. They really continued to try to have some kind of normalcy in their daily lives, even though they were in such a terrible predicament. I was really inspired by the fact that people would still attend a life drawing session or make an event or community events like that. Just to pass the time and try to pursue some kind of skill or education, even though they were incarcerated and they had no idea what their future held.

Erin: Yeah, I love that about our community. And I find that that helps me balance my emotions, you know, working in this subject matter as well. Like, just looking at these moments of resistance and resilience, you know, that sort of counteract against what I’m sure was a ton of depression and anger and sadness. So, I’m really glad you’re looking at that too.

Lauren: Yeah, it reminded me also of this historical photo that I found many years ago of Matisse painting from his bed. When he was very very ill, towards the end of his life, I think. And he had attached a paintbrush to the end of a very long stick and was painting murals on his own wall, in his bedroom, I guess. He couldn’t get out of bed but he was still making art like that. And I think art is such a powerful tool for self-healing, for getting through difficult times. I know this whole 2020 situation, if I wasn’t an artist, I don’t know how I would’ve handled it. Being able to meditate while doing art, and express yourself creatively, and have something productive to ground yourself. And I feel really, really lucky that it’s part of my daily practice, and it’s always been part of my daily practice, because I do think that it helps get people through tough times.

—

Lauren Iida ( she/her) was born in Seattle and holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Cornish College of the Arts (2014). Her main medium is intricately hand-cut paper, often incorporating layers of ink washed paper and focusing on negative space and shadow play. Iida shares her time between Seattle and Cambodia, exhibiting her work, creating public art installations, and mentoring and representing emerging contemporary Cambodian artists through Open Studio Cambodia, an arts collective that she founded. In the US, Iida is represented by Seattle’s ArtXchange Gallery. Her work has been exhibited at numerous venues throughout Washington state and collected by the City of Seattle Portable Works Collection (2016), King County Public Art Collection (2019) and the Washington State Arts Commission (2020). Iida has been commissioned to create temporary and permanent public art by The City of Seattle, The City of Shoreline, Washington State Convention Center Addition, The Office of Arts and Culture/Seattle Department of Transportation, The City of Bellevue, Plymouth Housing, and Sound Transit.

Erin Shigaki is a yonsei born and raised in Seattle, WA. While not formally trained in any single artistic practice, she considers her mother’s and grandparents’ artistic interests and encouragement to be foundational to her curiosity and exploration. In her emerging social practice, she infuses community stories into murals, sculpture, and installations. Erin is also a community activist with the Minidoka Pilgrimage, Tsuru for Solidarity, and serves on the board of the TV program Look Listen + Learn. All of this work is fundamental to her artistic practice.

[Header image: Lauren Iida’s 2nd Ave Sign Project on display at Common AREA Maintenance in Seattle. Photo courtesy of Lauren Iida Studio.]