January 23, 2023

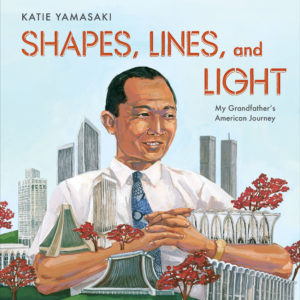

Artist and children’s book author Katie Yamasaki has traveled around the world creating murals and stories that explore issues of identity and social justice. Her latest book, Shapes, Lines, and Light, celebrates the life and legacy of her grandfather, acclaimed architect Minoru Yamasaki. Katie joined Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director Natasha Varner for a conversation about how Yamasaki’s childhood in pre-war Seattle and his later experiences as a Japanese American man building a career against the backdrop of WWII incarceration inspired him to create spaces to make people “feel fully human” — and what readers of all ages can learn from his story today.

Katie Yamasaki will share more about her new book at an all-ages event hosted by Densho, the Seattle Public Library, and Elliott Bay Book Company on Saturday, January 28th in Seattle. Learn more and reserve tickets.

Natasha Varner: First, I just want to say how much I love this book and how excited we are to have you come to Seattle to talk about it. And I know this is a place that figures pretty heavily into your grandfather’s life and creative outlook—can you tell us a little about how growing up in Seattle in the 1910s shaped him?

Katie Yamasaki: I think that the natural beauty of Seattle at that time—there was still so much of the city that was wild—and I think for him, nature was the place that he went to feel fully human when otherwise there were so many places and spaces that were denied to him and his community. [His family] lived in pretty significant poverty, but he would talk about the beauty of the waterways and the beauty of the natural landscape.

I think that when it comes to how he saw patterns in nature, and how that played heavily into his architecture later on, I’m sure that growing up in Seattle was a big part of that. And I think that the Seattle World’s Fair, in particular those arches at the Pacific Science Center, to me represent this kind of beautiful statement about how our emotional experience with a built structure is just as important as the practical ones—you know, the four walls and the roof—but also how can a structure uplift, and make you feel inspired or excited about the natural world? That those structures are in Seattle is pretty special, and also pretty relevant just to his experience with the natural environment that he grew up in.

NV: What made you want to write a book about your grandfather, and why’d you decide to do it at this stage in your career?

KY: I have wanted to tell his story since before I was an artist. I started graduate school like a week after 9/11 happened to pursue illustration and making children’s books. And when that happened people would say things like, “Oh, if you write your grandfather’s biography, it definitely could get published now.” [Ed. note: Minoru Yamasaki was the lead architect for the World Trade Center].

It was this awful circumstance of his work somehow becoming a symbol for pro-war propaganda. And it was pretty crushing to see these buildings that certainly weren’t his biggest artistic achievement, but they were his biggest professional achievement, to see that become this symbol for violence and aggression.

So I started thinking a lot about symbols and stories, and who gets to tell these stories. I started working on this book a few years after that, but I wasn’t ready to publish it because I felt like I needed to grow as an artist myself so that I could have enough space from his story to be able to tell it with a little bit of distance.

I wanted to have the time to really do it justice for my family. And so I think that the first thing was to create a lot of space between 9/11 and whenever the book would come out, because I didn’t want it to be remotely associated with 9/11. And so because of that, I think I needed a lot of time to pass, and also artistically for myself, I needed a lot of time to pass. From 2008 until 2019, I did five or six fully drawn drafts of this book. And each time I would do it, certain things would kind of fall away as no longer necessary.

Finally, in 2020 I took it on and it was a really good time to work on it particularly because, tragically, a lot of the circumstances of his life and the anti-Asian sentiment of the country that he experienced were happening again while I was working on the book. That was enraging and heartbreaking, but also made me feel like, well, this book really needs to come out because obviously we still need this content. And kids still need to understand the fact that these moments, these incidences of Asian hate are not happening in a vacuum. They’re happening in a huge context of the history of Asians in this country. So I’m glad that the book is out there as part of that story.

NV: Could you talk a little more about that context and, more specifically, how World War II incarceration and all the anti-Japanese sentiment surrounding it shaped your grandfather’s life and career?

KY: Well, he was married on December 5, 1941, to my grandmother, so two days before Pearl Harbor. She was a graduate student at Julliard, she was on a full scholarship to be a concert pianist. Her parents were Okinawan immigrants who lived in Los Angeles. My grandfather was able to work with his architecture firm to get his parents quickly evacuated from Seattle and take a train to New York. So during the war, he was living in a one-bedroom apartment with my grandmother, his parents, and his brother, Ken.

My grandmother’s whole family was sent first to the Santa Anita racetracks and then they were incarcerated in Amache. They lost my great-grandfather on that side. He was co-owner of a produce market or part owner of a produce market that sold wholesale produce to vegetable vendors. And he was, because of that he was considered a threat by the FBI. So he was arrested that first night, which meant that they lost all their money, they lost their livelihood. My grandmother’s sister had to drop out of college and her brother had to drop out of school. He ended up enlisting to get out of the camps.

But, yeah, I think that one thing that happened with my grandfather during the war was that he kind of became a symbol of success in the Japanese American community because he was able to work the whole way through and create quite a few prominent buildings. And so that put him in a position of incredible financial pressure because he was paying for many people, he was providing for many, but also I think it meant a lot to him that his success meant a lot to the community.

For a long time he couldn’t find work. When he first graduated, it was the Great Depression. And so he had moved out to New York, and he couldn’t find work at any firms. So he went back to graduate school at NYU to get his master’s in architecture and one of his first jobs was designing a naval base in upstate New York at the beginning of the war. When he was working on it, he was the lead architect on the project and he was denied entry. When he went to go and visit the site to see how the progress was coming along, they thought he was a spy.

I think that in New York City, things were different because the Japanese weren’t incarcerated there, but it wasn’t that there wasn’t this racist sentiment. So people would ask him on the subway if he was Chinese or Japanese. He was investigated by the FBI, by the NYPD. It was not an easy time.

I work within a lot of communities impacted by incarceration now, and you see that there are the people who are incarcerated, and then the impact on the overall community is also profound. And I think that that further deepened this feeling of wanting to create spaces where people could feel truly seen and feel fully human.

NV: In the author’s note, you talk about how many critiques of your grandfather’s work were rooted in racism and negative stereotypes relating to his Japanese American identity—can you say more about that?

KY: For me, it’s impossible to separate when people are starting an architectural review by talking about his small frame, his diminutive stature, you know, and then talking about his effeminate forms as decorative and excessive and things like that, it’s really hard for me to isolate that from the way Asian men have forever been considered in our country as emasculated, as petite, as less-than. And so I would think about how that would impact him.

And I’d heard plenty of family stories about how hard these reviews sometimes landed. And he was from a public university, the University of Washington, and from a poor family in a field that is the field of white elitism. This was the world that he lived in and I think that, on the one hand, it made him feel the need to prove himself on a constant basis and prove his worth, and prove the worth of his work. On the other hand, I think it enforced the need that he already felt to create these spaces where people could feel fully human, and have a fully human, expansive emotional experience.

So these emotional experiences around making art and being a person of color in this country, it all intermingles and also impacts how people receive your work. I often will think about not just what the impact was on him, but what the impact was on his whole family. You know, if your dad comes home from work after being spoken about like this in a broad public forum of your professional peers, how devastating that is. I always think whenever I’m looking at art that I don’t like or agree with, but just try to get at the intention of the artist before I try to judge it or take it down. So that’s something I learned from him.

NV: That reminds me of a line from the book: “Every bitter sound made a brick. Every brick built a stronger foundation.” That really struck me because it’s a beautiful way to talk about resilience, but it also recognizes the weight that racism and injustice has on the people who are targeted by it.

KY: Yeah, it’s interesting because I think about, like, if he had been born in a time where his inherent worth as a human being was a given, I wonder what his accomplishments would have been. I wish that people didn’t grow up feeling that they needed to prove themselves and prove their worth, and prove their value and work to the point of being unwell in order to feel like they matter. And what I hope is that when kids read this book, they’ll think about their own inherent value as a starting point with whatever they choose to pursue.

Learn more about Shapes, Lines, and Light: My Grandfather’s American Journey by Katie Yamasaki here.

[Header image: Page excerpt from Shapes, Lines, and Light, courtesy of Katie Yamasaki.]