October 29, 2020

The rescue of the “Lost Battalion” holds a near-mythical place in Japanese American history. Over the years, dozens (if not hundreds) of films, novels, memoirs, history texts, exhibitions, and even children’s books have told some variation of the story. The impressive record of the 100th Infantry Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team—and this famous battle in particular—is widely credited with improving public perception of Japanese Americans in the years following World War II. As President Truman told members of the 442nd at the White House in July 1946, “You fought the enemy abroad and prejudice at home and you won.”

While there is certainly much more nuance and complexity to the story, that mythos is easy to understand. The rescue of the Lost Battalion is a story of immense courage in the face of a terrifying, impossible situation. It’s a story of what people are capable of when their survival is on the line. But more than 75 years and at least three generations of war later, I hope we can also recognize it as a story of the hazards of careless and ego-driven leadership, the ways some lives are appraised at higher value than others, and the unequal sacrifices demanded of Japanese Americans during WWII.

How the “Lost Battalion” got lost

The 36th Infantry Division—which included both the 442nd and the ill-fated “Alamo Regiment”—had spent most of October 1944 in eastern France, engaged in heavy fighting on harsh terrain. When the 442nd was ordered to attempt the rescue of the Lost Battalion, they had just finished nine straight days of fighting against German troops entrenched in the densely-forested Vosges mountains. Perhaps foreboding events to come, the Japanese American soldiers of the 100th Battalion (which was by then part of the 442nd) was at one point ordered to march beyond the nearest friendly troops and cut off from the rest of the unit. They held out in the cellars of abandoned houses for two days, until help arrived from the 3rd Battalion.

The men were supposed to have five days of well-deserved and much needed rest—a time to, as Fred Shiosaki bluntly put it, “no longer worry about, this guy gonna take a shot at you, or artillery shell’s gonna land or something.” But that rest would be short-lived.

Instead, they were roused up in the middle of the night and ordered back to the Vosges mountains to rescue 275 lost Texans trapped behind enemy lines. It was the first time most of the men had slept in over a week, barely a day-and-a-half after the brutal Bruyères-Biffontaine campaign.

The 141st Regiment, like the 442nd a few days earlier, had been ordered to march beyond the nearest Allied troops to capture more French territory. And like the 442nd, their concerns that the human cost of the mission outweighed its strategic importance were ignored by higher-ups. The 1st Battalion was soon cut off from the rest of the regiment and surrounded. But unlike the 442nd, attempts by the 141st’s other two battalions to rescue the stranded soldiers were unsuccessful. By the time the Nisei soldiers were recalled, the Lost Battalion had been under siege by German troops for two days and was already running dangerously low on food, water, ammunition, and medical supplies. A fighter squadron had tried airdropping supplies to the men, but most of the packages landed in German-occupied positions.

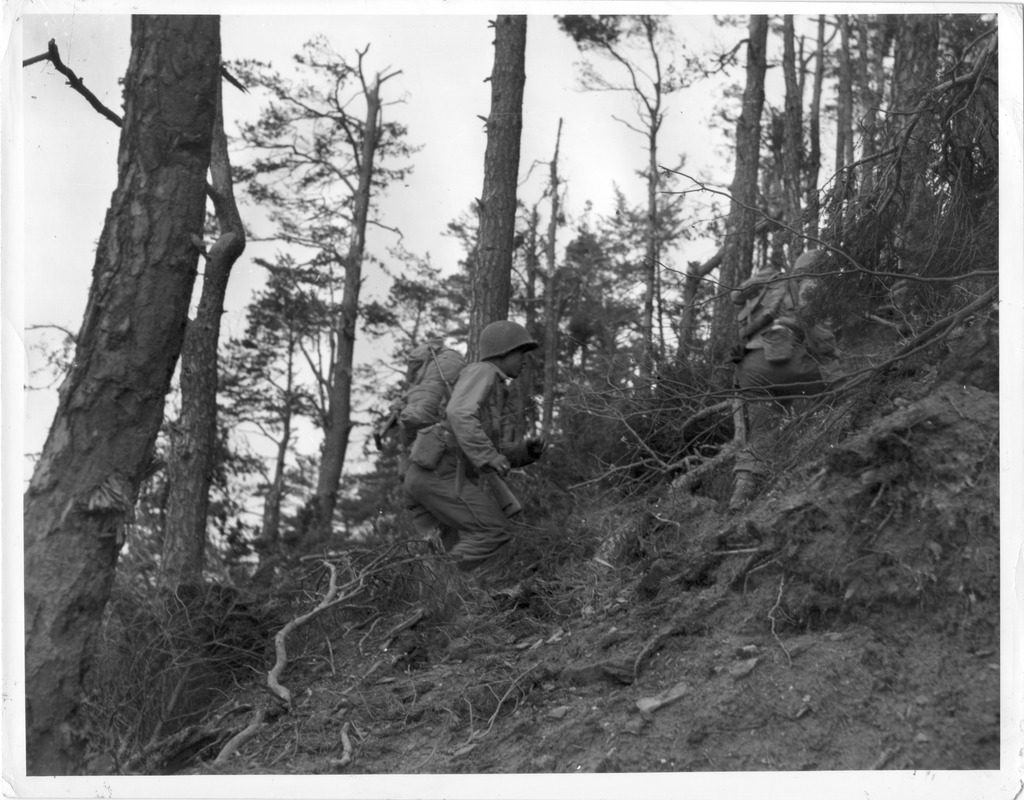

So in the early, pre-dawn hours of October 25, 1944, the 442nd set out to reach the Lost Battalion. They trudged through miles of heavily mined fields and steep ravines in the mud and icy rain, each holding onto the man ahead of him because the fog was too thick to see more than a few feet ahead. As one soldier later recalled, “it was blacker than the inside of a wolf.”

A devastating rescue campaign — “Was it because we were Japanese?”

Over the next six days, the Nisei soldiers of the 442nd and the attached 522nd Field Artillery Battalion attempted to break through the entrenched German lines. They were outnumbered four to one at times—the lines so close together that the Nisei had to jump into trenches to avoid their own artillery fire. Later, when the fighting was over, they’d learn that Adolf Hitler himself had gotten wind of the battle and ordered that the Lost Battalion must not be rescued, no matter the casualties.

On the American side, too, General John Dahlquist put similar pressure on the 442nd to secure a victory at any cost. Many of the Japanese American soldiers, and even their white commanding officers, questioned whether any other unit would have been pushed so far.

“How come they don’t use the other regiments to help the battalion,” Larry Sakoda asked in a 1998 interview. “To use only the Japanese outfit, and not his own men. That was, I don’t know, made us really mad.” Rudy Tokiwa was more direct: “Well, what the hell was this damn deal, where he has three times the amount of men that we have. Why didn’t they go in and make the risk? It was their own people. Why us? Was it because we were Japanese?”

On October 30, 1944, the 442nd was finally able to push through one last German artillery barrage and reach the Lost Battalion. 211 of the 275 trapped Texans were saved. But the losses for the Nisei unit were devastating, with at least several hundred wounded or killed. It was the worst fighting they’d encountered since landing in Europe, and the men reasonably expected to be dismissed for a period of rest. But Dahlquist instead ordered them to continue chasing the Germans through the forest to secure additional territory. It was another nine days before they were finally allowed to rest—a total of more than three weeks of almost nonstop combat for the entire Vosges campaign, costing approximately 150 deaths and over 1,800 wounded.

Four days after the 442nd was finally relieved, on November 12, 1944, Dahlquist ordered a now-infamous parade review. Less than half of the men in the unit were still standing. The general took the poor showing as a personal affront and accused the Nisei of failing to turn out, before being informed that “the rest are either dead or in the hospital.”

There is a photo of this review. The Nisei soldiers stand at attention on a frostbitten field somewhere near Bruyères, the fog heavy enough to hide the surrounding forest. If you look closely, you can see small deposits of snow atop boots and helmets, a white medic’s armband, a wedding ring. Noticeably absent is the rigid military order you’d expect from the most highly decorated unit in American history (for its size and length of service).

The men look exhausted to their bones, helmets askew and arms alternately hanging at their sides or clasped behind their backs. One lilts to the side, his weight shifted onto his left leg while his rifle rests casually against the right. The soldier bearing the American flag shuts his eyes as if steeling himself to get through the moment, while the color guard next to him looks somewhere off camera, his eyes low to the ground and unfocused.

Looking at this photo today, it’s hard not to read into the soldiers’ expressions. To ascribe certain emotions to a clenched fist there, a hard stare here. I catch myself searching for signs of the same anger and grief I feel when I remember the sacrifices these young men—and those in other units, like my great-uncle Frank Kubota of the MIS—were asked to make for a freedom denied to many of their own families. We tend to romanticize them, transform them into symbols of “Go For Broke” stoicism rather than individual people with thoughts and feelings and memories of their own. But who do we serve with this celebration of superhuman sacrifice and quiet, uncomplaining endurance?

The legacy of the Rescue of the Lost Battalion

Fred Shiosaki participated in both the liberation of Bruyères and the rescue of the Lost Battalion. In a Densho interview decades later, he described being “scared all the time”: “Combat is something just completely different… until you experience it and survive it, you can’t describe what the hell goes on.”

Mits Takahashi, who joined the 442nd soon after the Vosges campaign, recalled observing intense trauma in the surviving soldiers:

“My first impression when I joined the 442 is the fellows that had gone through the Battle of the Lost Battalion and the Battle of Bruyères and things, they looked like insane people. They just… I mean, it was frightening to look at ’em. They were so traumatized in so many ways that you knew that they had gone through an awful lot. I mean, they were stressed out, and my first impression was, ‘My God, these guys are scary to look at.’”

We don’t often associate soldiers with vulnerability, or perhaps more accurately, don’t allow them to expose vulnerability. Fear, uncertainty, empathy—these are liabilities, weaknesses that must be buried deep down and closely guarded in order to survive. But without an honest accounting of the layers upon layers of trauma we have asked these men to carry over the last seven-and-a-half decades, there is no room for healing. I think these men—our fathers, grandfathers, uncles, cousins—have sacrificed enough.

The men of the 442nd did something remarkable and truly selfless in the rescue of the Lost Battalion. I believe we can hold space for both gratitude for what they gave—to the 211 Texans whose lives they saved, to the people of Bruyères and Biffontaine, to the Japanese Americans whose increased acceptance was bolstered by their battle record—in addition to an interrogation of why they were asked to give so much. These men fought and died because, despite the many degradations and prejudices they’d experienced at home, they believed this nation’s promise of “justice for all.” We can honor that legacy by reckoning with the uncomfortable truths lurking beneath the ganbatte veneer, and fighting for a world where our young people can live long and peaceful lives without being asked to prove their loyalty in blood.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator

[Header photo: The parade review of the 442nd RCT ordered by General John Dahlquist on November 12, 1944. Courtesy of the Seattle Nisei Veterans Committee and the U.S. Army.]