June 2, 2021

Do you have a burning question about Japanese American history? A piece of family lore you’re not sure is myth or fact? Brian Niiya, Densho’s Content Director and basically a walking encyclopedia of all things related to WWII incarceration, has got you covered. He’ll be answering real questions from real people in this new, recurring series—so ask us anything!

At Densho, we receive many questions about the World War II removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans and related topics. The ones that go beyond the basics usually end up in my email box. While I try to answer as many as I can, I don’t always have the time to provide an individual answer. But a good number of the questions are interesting ones that I think our general audience would enjoy learning about as well. Thus, this new feature on our blog.

Let’s start with one of the questions we get most often, one asked most recently by a TV producer researching the history of anti-Asian American violence:

Why do some accounts list the total number of Japanese Americans incarcerated as 110,000, while others use 120,000? Is there a definitive figure we should be using?

There is a fairly simple answer to the question, but also a much more complicated one.

The simple answer is that the two figures are both correct, but for slightly different reasons. The 110,000 figure is the approximate number of Japanese Americans who were forcibly removed from the West Coast in the spring and summer of 1942 under the auspices of Executive Order 9066 and who subsequently entered the “assembly centers” run by the Wartime Civil Control Administration or the concentration camps run by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). The 120,000 figure is the total number of people who came under the jurisdiction of the WRA, or the total number of Japanese Americans held in the WRA camps at one time or another. So it would be correct to say that “about 110,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from the West Coast” and that “about 120,000 Japanese Americans were held in American concentration camps administered by the War Relocation Authority during World War II.”

The extra 10,000 people are those who entered the WRA camps after the initial roundup. There were three large groups who made up the bulk of this 10,000. Over 1,700 transferred from the Department of Justice internment system, mostly from the summer of 1942 to early 1943. These were by-and-large Issei men who had been arrested and interned after the attack on Pearl Harbor but before EO 9066. Unlike those held by the WRA, these men were given hearings and as a result of these hearings, some were paroled. Most of these “parolees” were sent to WRA camps, where they were still imprisoned, but could at least be reunited with their families.

A second large group were the over 1,100 from Hawai`i who were sent directly to WRA camps in four shipments between December 1942 and March 1943. This group included family members of male internees who hoped to be reunited with their husbands/fathers as well as those deemed either security risks or drains on the economy, including a substantial number of fishermen who had had their boats confiscated and been driven out of business under martial law. About 80% of the Hawai`i group was sent to Jerome, with the rest sent to Topaz. But by far the largest group were the nearly 6,000 babies who were born in the WRA camps. Along with a few other smaller clusters, these groups along with the 110,000 in the initial roundup add up to the oft cited 120,000 figure.

There is also a more complicated answer. In addition to the 120,000 who were in the WRA system, there were some number of incarcerated Japanese Americans who were not. These fall into two groups: (a) those who went to the “assembly centers” but not to WRA camps and (b) those who were interned in Justice Department- or army-run camps who did not enter the WRA system. As such, the actual number of incarcerated Japanese Americans was somewhat higher than 120,000.

Based on figures in the army’s final report, there were around 800 Japanese Americans who went to assembly centers but never made it to the WRA camps. This includes those who resettled directly out of the assembly centers—scholars John M. Maki and Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi were among this group—as well as those who died in the assembly centers or who repatriated or expatriated to Japan.

The calculations for the second group are much more complicated. Tetsuden Kashima’s Judgement without Trial lists a total of 17,477 Japanese Americans (and Japanese Latin Americans) who were interned by the Department of Justice. However, most of these people were also in WRA camps and thus would already be counted in the 120,000 figure. I won’t go into details here, but based on Kashima’s figures and other data, I’ve estimated that about 5,500 Japanese Americans were interned in DoJ camps but not in WRA camps. Most of these were interned Issei community leaders who were not paroled to WRA camps and who remained in custody for the duration of the war, people like Kumaji Furuya or Masuo Yasui. Added to the 800 or so who were in the assembly centers but not the WRA camps gives us a figure of some 6,300 additional inmates beyond the 120,000 figure. For this reason, Densho has been using a figure of 126,000 as an estimate of the number of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II.

There is an ongoing project led by Duncan Williams at USC to identify the names of everyone incarcerated in any of the detention facilities that held Japanese Americans during World War II. As a by-product of that research, we should be able to finally arrive at a definitive figure.

Next, a question from Fran:

I just read your article “Terrorist incidents against West Coast returnees.” It reminded me of a ‘story’ which was related to me by my father LONG ago. I am wondering if this incident actually happened or if it was a ‘rural’ legend? He was usually quite accurate and not prone to ‘negative’ comments.

We lived in the Watsonville-Salinas areas before and after the war. I had always assumed this alleged incident happened here, partly because I do not recall him mentioning the family’s name: A family had been harassed by local residents and one night it was a group of teenagers. The father in exasperation fired in the general direction of the group. A teenager was fatally shot. I asked what happened to the farmer and he said no charges were made, because the police knew the family had been repeatedly targeted.

Is there any record of such incidents and where did they occur? (I know there was a MOST antagonistic reception in this area.)

I have not come across any incident that resembles the story passed down by your father in looking at various Japanese American newspapers in the years after the return to the coast starting in 1945. My guess is that this is a “rural” legend. Many urban legends have a wish fulfillment element to them, and this would seem to fit into that category.

At the same time, it is very difficult to prove something like this didn’t happen. Does anyone out there recall hearing a story like this in which there are details that would allow us to more carefully investigate?

If you have any questions you would like to ask—or if you have comments or additional information about any prior questions—write to us at info@densho.org or just leave a comment below.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

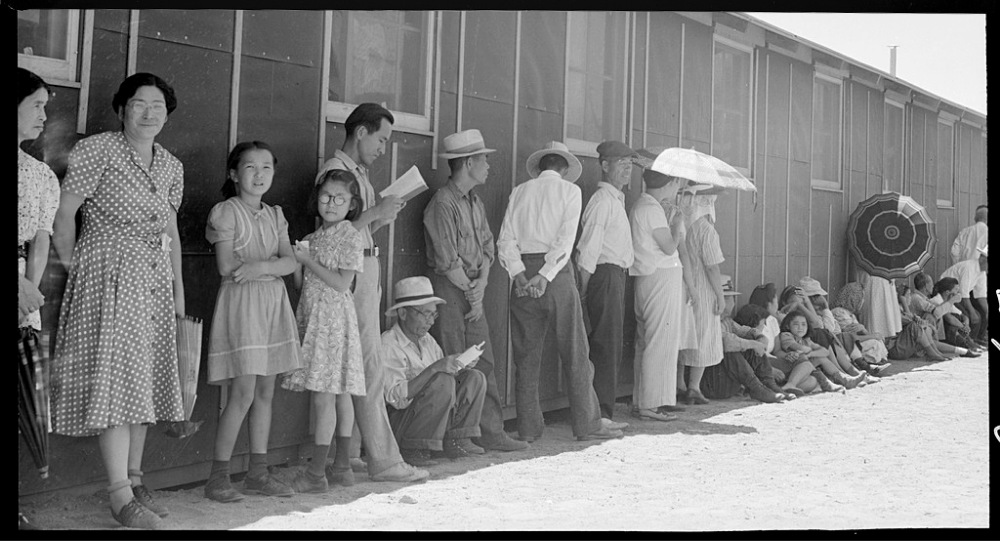

[Header: Part of a line waiting for lunch outside the mess hall in Manzanar. Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]