November 13, 2025

This post concludes our three-part series on teaching with the Densho Digital Repository. Building on earlier guides about navigating the archive and teaching difficult histories, this article presents Densho’s pedagogical approach to teaching Japanese American incarceration.

Each letter, photograph, and oral history in the Densho Digital Repository represents a family’s act of trust—the belief that sharing personal, and sometimes painful, experiences can ensure this history lives on. Grounded in Densho’s values and collaboration with the Japanese American community, this final installment in our series on teaching with the Densho Digital Repository invites educators to approach these materials with the same care our archivists bring to preserving them. It offers pedagogical guidance for teaching Japanese American incarceration during World War II so that students can engage with this history critically, empathetically, and with a sense of responsibility.

There is no single “right” way to teach Japanese American incarceration. Just as Densho’s collections hold many perspectives, effective pedagogy requires multiple entry points. These approaches often overlap—an Ethnic Studies lens might shape inquiry questions, while teaching with care might guide how we introduce an oral history. Together, they reflect Densho’s belief that teaching this history is about cultivating relationships with the material, with students, and with the communities whose stories we carry forward.

Teaching with Densho’s Digital Repository: Engaging Evidence and Community

Teaching with Densho’s Digital Repository invites students to engage directly with primary sources—letters, photographs, oral histories, and government documents—to construct meaning rather than relying solely on secondary interpretation. Centering the perspectives of families and individuals who experienced incarceration, rather than only official documents like Executive Order 9066, helps students understand how people navigated loss, uncertainty, and resilience in real time.

Because Densho’s collections are contributed by community members, they capture intimate details often absent from traditional archives: handwritten letters, family albums, and oral histories that reveal how ordinary people lived through extraordinary injustice. Yet, as with all archives, not every perspective is present. Some stories were never documented or have been lost to time. Recognizing these silences is as important as studying what remains—it teaches students to think critically about whose histories are preserved, whose are missing, and why.

Educators can use sources from Densho’s Digital Repository alongside secondary sources such as textbooks or children’s books to help students move beyond simplified or single-story representations of Japanese American incarceration. Pairing these texts with Densho’s primary sources allows students to compare narratives, analyze accuracy, and recognize what voices or details are missing from the broader record.

Inquiry: Developing Historical Thinking

Inquiry-based teaching positions students as investigators who ask questions, analyze evidence, and construct interpretations—an approach central to the C3 Framework for Social Studies and to developing critical, informed citizens. Building on Peter Seixas’s framework of historical thinking concepts—evidence, significance, continuity and change, cause and consequence, perspective-taking, and the ethical dimension—teachers can guide students beyond a linear narrative of Japanese American incarceration (Pearl Harbor, camps, apology) to examine the deeper causes and consequences of injustice. Through questioning and analysis, students can trace how fear, law, and racial ideology intertwined to shape decisions and policies. Teachers can also help students avoid presentism by grounding their interpretations in the historical context of the 1940s while still acknowledging the human cost of those choices.

Seixas’s work and that of scholars like Lindsay Gibson underscores that ethical judgment and ethical reasoning allow students to weigh historical context against moral responsibility. Students are tasked to consider not only what happened and why, but also what was at stake and what obligations exist today. Gibson, Milligan, and Peck stress that ethical judgement “humanizes history” by connecting the study of past injustices to the lived ethical choices of the present.

Inquiry Design Models offer a framework for teachers to structure units around compelling questions and to ask students to apply historical thinking concepts. By using the Densho Digital Repository, teachers can curate primary sources that center the experiences of Japanese Americans. Students can explore various questions by analyzing government orders, propaganda photographs, and oral histories to evaluate competing narratives. Their learning might culminate in a discussion, written reflection, or creative project that synthesizes evidence and spurs them to take informed action, connecting the incarceration to present-day struggles.

Moreover, as Noreen Naseem Rodríguez, Sohyun An, and Esther June Kim point out in Teaching Asian America in Elementary Classrooms, “True inquiry gives students opportunities to develop their own questions,” citing that this strategy drives engagement. This kind of open-ended exploration drives engagement and empowers students to become co-constructors of historical understanding. By encouraging students to ask and refine their own questions through the Densho Digital Repository, educators can help them see history as an evolving process of discovery—one that connects evidence to empathy, and critical thinking to civic responsibility.

Teaching with Care: Honoring the Emotional Legacies of History

Japanese American incarceration was a collective trauma—marked by forced removal, imprisonment, and the loss of home, rights, and community. As Naomi Ostwald Kawamura and Tobias Ryan (2021) note in their study of the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre, caring for histories of racial trauma also means tending to the emotional legacies—both collective and intergenerational—that accompany them. This insight underscores a truth that extends beyond museums: when educators teach about injustice, they enter into the emotional legacies of those histories. Teaching with care, like archiving with care, requires empathy, transparency, and consent.

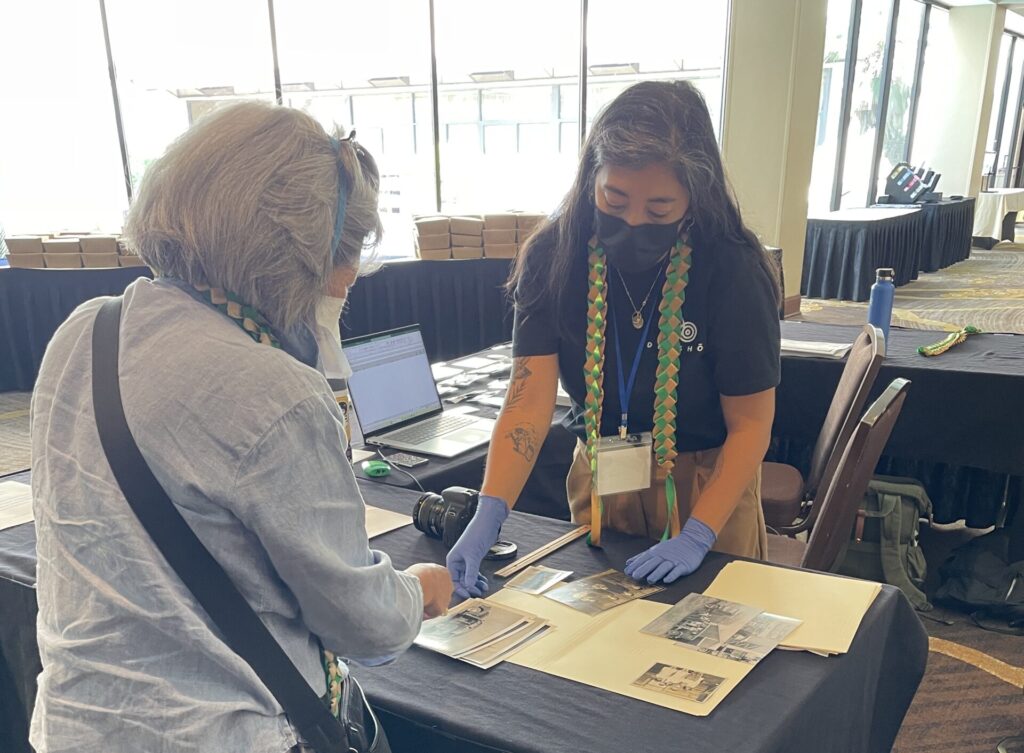

At Densho, compassion and consent are foundational to how we preserve and share memory. Donors retain full control over what is made public; individual photos, letters, or passages from oral histories can be kept private or redacted at any time. This practice reflects Densho’s commitment to community agency and emotional safety: honoring stories without exploitation. Educators can mirror this same ethic in the classroom by creating conditions that prioritize trust, choice, and respect for emotional boundaries.

In practice, this might mean co-creating community agreements before introducing sensitive materials, allowing students to opt out of specific discussions, or pairing challenging sources—such as photographs of forced removal or testimonies from camp life—with accounts of care, creativity, and postwar activism. Kawamura and Ryan suggest that museum educators can draw on strategies such as self-awareness, nonverbal attending, and reflective listening when encountering grief; teachers can use similar approaches to create presence and support in the classroom. These strategies help students engage with both pain and perseverance, learning that history is not only about what was endured but also about how people rebuilt, resisted, and remembered.

Ethnic Studies: Building Critical Consciousness

Ethnic Studies emerged from the student movements of the late 1960s, led by Black, Asian American—including Japanese American—Latine, and Native students who demanded that education reflect their communities’ histories and struggles for justice. The field cultivates critical consciousness: the ability to question power, challenge dominant narratives, and connect personal and collective histories.

The incarceration of Japanese Americans illuminates the very structures that Ethnic Studies was created to critique: systemic racism, xenophobia, and state-sanctioned injustice. Many of the activists who helped launch the Asian American Studies movement were shaped by this history, drawing lessons from their families’ incarceration and the postwar fight for redress. Teaching incarceration through this lens helps students see it not as an isolated wartime event, but as part of a continuum of exclusion, resistance, and community activism.

Educators seeking models for this kind of instruction can look to the UCLA Asian American Studies Center’s Foundations and Futures digital textbook, which features many of Densho’s primary sources in addition to lesson plans on Japanese American incarceration explicitly grounded in an Ethnic Studies framework. These lessons align closely with the Asian American Studies Curriculum Framework, which emphasizes inquiry, criticality, and solidarity across communities. As educator Christian-Joseph Macahilig explains, “…we’re not only preserving history—we’re creating spaces where communities can see themselves reflected in the broader American story. That’s how we democratize and humanize history: by ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to see their story as part of the collective ‘we.’”

Densho’s post-custodial archive embodies this same Ethnic Studies approach to democratizing history. Each oral history, photograph, and family collection is preserved not as static evidence, but as living knowledge: counter-narratives that return power to the communities who created them and invite students to see history as a shared, evolving story.

Accessibility: Expanding Reach and Centering Voices

From the beginning, Densho has understood access as both a technical and ethical commitment. The Densho Digital Repository is free, fully online, and easily searchable—removing barriers that often limit who can engage with archival materials. Object-level descriptions and human-written transcriptions of oral histories make the collections more discoverable and accurate, while the absence of paywalls ensures that anyone—from researchers to community members to students—can explore this history.

Equally important, Densho’s approach to accessibility centers Japanese American voices rather than relying solely on government records. By digitizing family photographs, letters, and oral histories, Densho ensures that personal and community perspectives are preserved alongside official narratives, allowing students to encounter history through multiple modalities.

For educators, accessibility means designing lessons that invite all students into the work of historical inquiry. The Digital Repository naturally supports multimodal learning, offering visual, oral, and written sources that can be adapted for different classrooms and learning needs. When teachers pair this with thoughtful scaffolding, such as providing context, vocabulary, and guiding questions, they model accessibility as inclusion: ensuring that every learner has the tools and opportunity to participate fully in constructing historical understanding.

From Remembrance to Responsibility

When taught with care, context, and community at the center, the history of Japanese American incarceration becomes more than a lesson about the past—it helps students understand how fear, racism, and silence can erode justice. They learn that remembrance is an act of repair and that history offers both warning and possibility. Through inquiry, accessibility, and empathy, students recognize how language shapes power, how systems can both harm and be challenged, and how people resist even within structures of oppression. Teaching in this way ensures that this history remains alive in the classroom, cultivating awareness, accountability, and the courage to act with care in the present.

—

Written by Densho Education & Public Programs Manager Courtney Wai and Executive Director Naomi Ostwald Kawamura. This post is the third in a three-part series on teaching with the Densho Digital Repository. The first installment explores how educators can search the archive, and the second examines strategies for teaching difficult histories with care. Subscribe to Densho’s quarterly Education eNews now!

[Header: Fourth grade school in Barracks 35-4-B at Rohwer incarceration camp. Teacher is Nareen Oura. November 24, 1942. Photo by Tom Parker. Courtesy of CSU Japanese American History Digitization Project.]