January 27, 2016

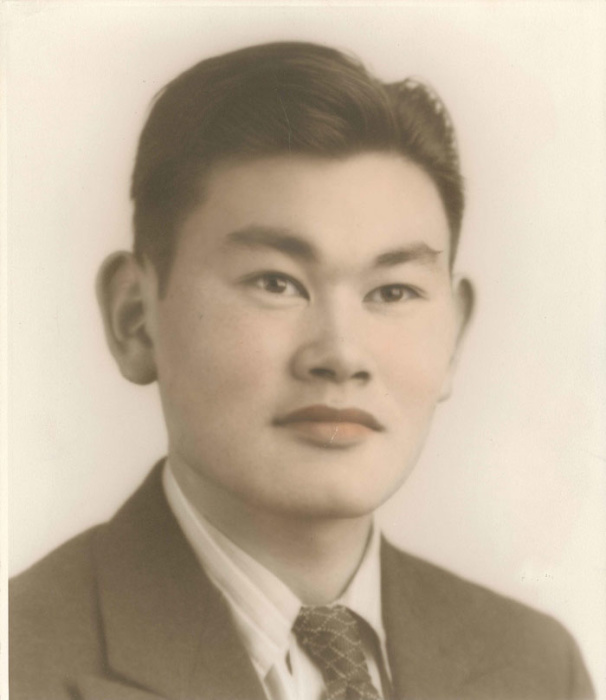

Korematsu was born on January 30, 1919, to Japanese parents who ran a plant nursery in Oakland, California. He worked as a shipyard welder after graduating from high school until he lost his job after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was 22 when the U.S. plunged into war. On May 9, 1942, his parents and three brothers reported to the Tanforan Assembly Center, but Korematsu stayed behind with his Italian-American girlfriend. By then, the army had issued a series of exclusion orders that prohibited Japanese Americans from being inside Military Area No. 1. In an attempt to disguise his racial identity, he changed his name and had minor plastic surgery on his eyes to appear European American. His refusal to comply with the evacuation order led to his arrest on May 30, 1942.

While in jail, he was visited by Ernest Besig, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California. Korematsu agreed to become the subject of a test case to challenge the constitutionality of President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 along with fellow resisters Min Yasui and Gordon Hirabayashi. Although Besig paid Korematsu’s $5,000 bail, Korematsu was sent to Tanforan immediately after his release. After the federal district court in San Francisco found him guilty of violating military orders, his court case went to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944. The high court upheld the lower court’s ruling in a 6-3 vote. (See Korematsu vs. U.S.)

In the 1980s, legal historian and author Peter Irons filed a petition to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court in San Francisco to have Korematsu’s conviction overturned on the grounds that the Supreme Court had made its decision based on false information. Korematsu spoke at the courtroom and said, “As long as my record stands in federal court, any American citizen can be held in prison or concentration camps without a trial or a hearing.” In November 1983, U.S. District Judge Marilyn Hall Patel vacated Korematsu’s conviction and argued that the Korematsu case serves as a “caution that in times of distress the shield of military necessity and national security must not be used to protect governmental actions from close scrutiny and accountability….”[1]

After the successful coram nobis petition, Korematsu continued to advocate for civil rights at countless colleges and law schools. In 1999, he received a Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian hono r. After 9/11, he filed an amicus—or “friend of the court”—brief with the Supreme Court for two cases on behalf of Muslim inmates being held at Guantanamo Bay. He filed another amicus brief in 2004, citing similarities between the wrongful imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II and Muslims following 9/11. He passed away of respiratory illness on March 30, 2005.

r. After 9/11, he filed an amicus—or “friend of the court”—brief with the Supreme Court for two cases on behalf of Muslim inmates being held at Guantanamo Bay. He filed another amicus brief in 2004, citing similarities between the wrongful imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II and Muslims following 9/11. He passed away of respiratory illness on March 30, 2005.

On January 30, 2011, California held its first Fred Korematsu Day, the first day in the U.S. to be named after an Asian American, commemorating his lifetime of service defending the constitutional rights of Americans.

Fred’s legacy continues to live on through the work of his daughter, Karen, and the Fred T. Korematsu Institute. Through educational programs and annual Fred Korematsu Day events, the Institute increases awareness of “one of the most blatant forms of racial profiling in U.S. history, the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.” Karen Korematsu carries on her father’s legacy through continued engagement with contemporary civil rights issues. This year’s Korematsu Day celebration addresses the rise of anti-Muslim sentiment through the theme, Re(ad)dressing Racial Injustice: From Japanese American Incarceration to Anti-Muslim Bigotry. In the future, the Institute plans to lobby for a national commemorative holiday recognizing Fred Korematsu, who would be the first Asian American to have a national holiday, and to create a museum/library learning center.

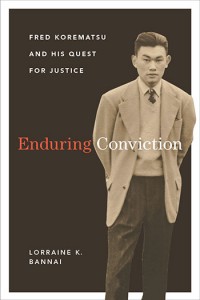

In 2015, Lorraine K. Bannai, a member of the legal team that successfully challenged Fred Korematsu’s conviction, published Enduring Conviction: Fred Korematsu and His Quest for Justice. George Takei endorsed the book—and Fred—saying, “A remarkable story of a man who stood up and spoke out in the same tradition of others in this country who have spoken out against oppression and discrimination…Fred Korematsu was an ordinary man who did extraordinary deeds and with that he made history.”

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications Manager

Material excerpted from the Densho Encyclopedia entry on Fred Korematsu by Shiho Imai.

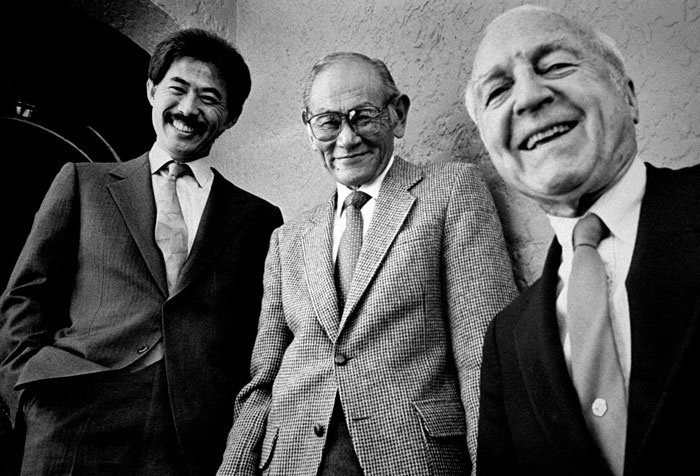

[Header photo: Fred Korematsu, center, with ACLU lead counsel (1982-1983) Dale Minami and ACLU attorney (1942-1944) Ernest Besig. Photo by Shirley Nakao, courtesy of the Korematsu Institute.]