September 13, 2022

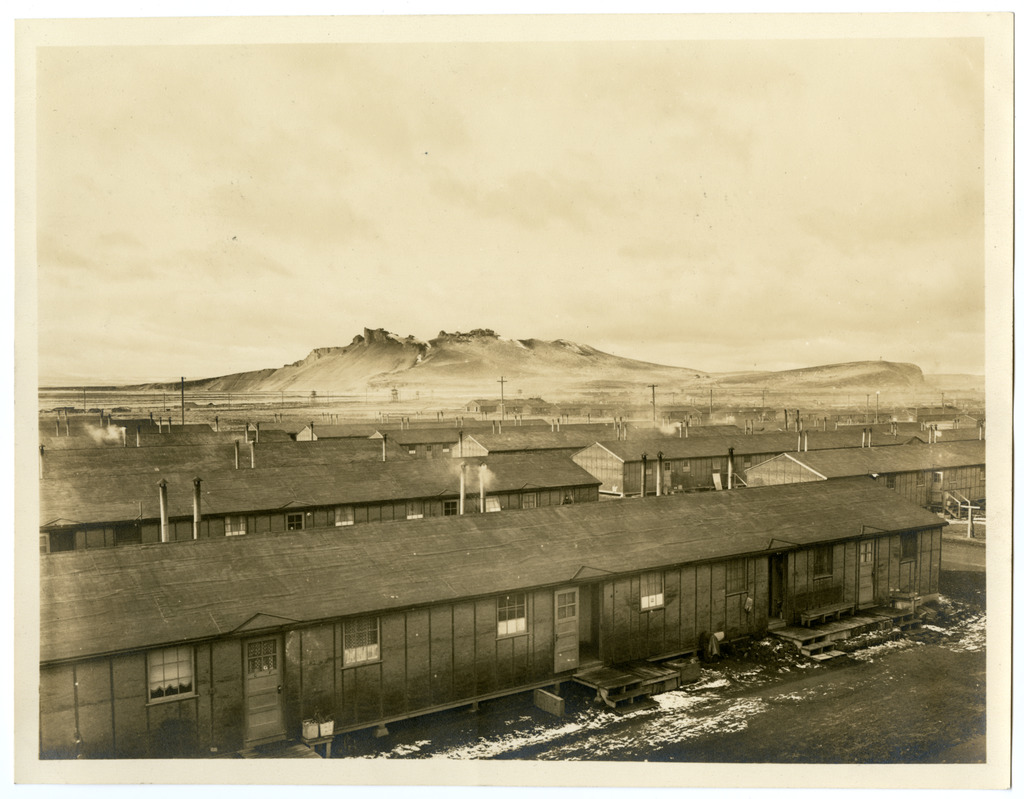

Shootings by guards, martial law, divided loyalties among families, intra-camp conflicts and antagonistic administrators, and mass renunciations of U.S. citizenship all contributed to making Tule Lake—initially one of ten War Relocation Authority camps, but later dubbed a “segregation center”—a site of suffering. During the two chapters of its existence, Tule Lake inspired four poets to write about the incarceration in different ways. All of them participated in small, pre-war poetry circles around the West Coast, wrote poetry during their incarceration, and left their impact on Asian American literature. All of them also wrote in Japanese and English, with some of their poems appearing in both languages. Here are profiles of these poets, with examples of their work.

Bunichi Kagawa (1904-1981)

Literary scholar Stan Yogi describes Bunichi Kagawa as the Issei writer who had the “closest link with the Japanese American communities,” and has been praised by writer Ishmael Reed as the “most interesting of the immigrant poets.”1 Among the first Japanese American poets, Kagawa established himself in the early 1930s among poetry circles around San Francisco.

Originally born in Japan in 1904, Kagawa immigrated to the United States in 1918 and lived with his father in Los Altos, California. He studied at nearby Stanford University, where he met poet and literary scholar Yvor Winters. Winters took the young Kagawa under his wing and jump started his career by co-authoring with Kagawa the poetry volume Hidden Flame in 1930. Soon after, Kagawa began sending his verses to various publications, and his poems appeared in the pages of Poetry Magazine and Stanford’s Carillon Magazine. Kagawa’s fame spread within the Japanese American community; he helped form a poetry circle among Japanese Americans in northern California, and several community newspapers such as the Rafu Shimpo and Kashu Mainichi published his poems.

In the wake of Pearl Harbor, Kagawa joined several other writers and artists, including Isamu Noguchi and Ayako Ishigaki, to form an anti-fascist circle to support the American war effort. Soon after Executive Order 9066, Kagawa was incarcerated at Tule Lake concentration camp. Following the segregation program in 1943, Kagawa and several Kibei writers—Masao Yamashiro, Jyozi Nozawa, and Kazuo Kawai —began a literary magazine in camp.2 Titled Tessaku, or “iron gate,” the magazine incorporated a variety of poems, short stories, and essays. While Kagawa could not serve as an editor because he was an Issei, his contributions to Tessaku reflected his influence on the publication.

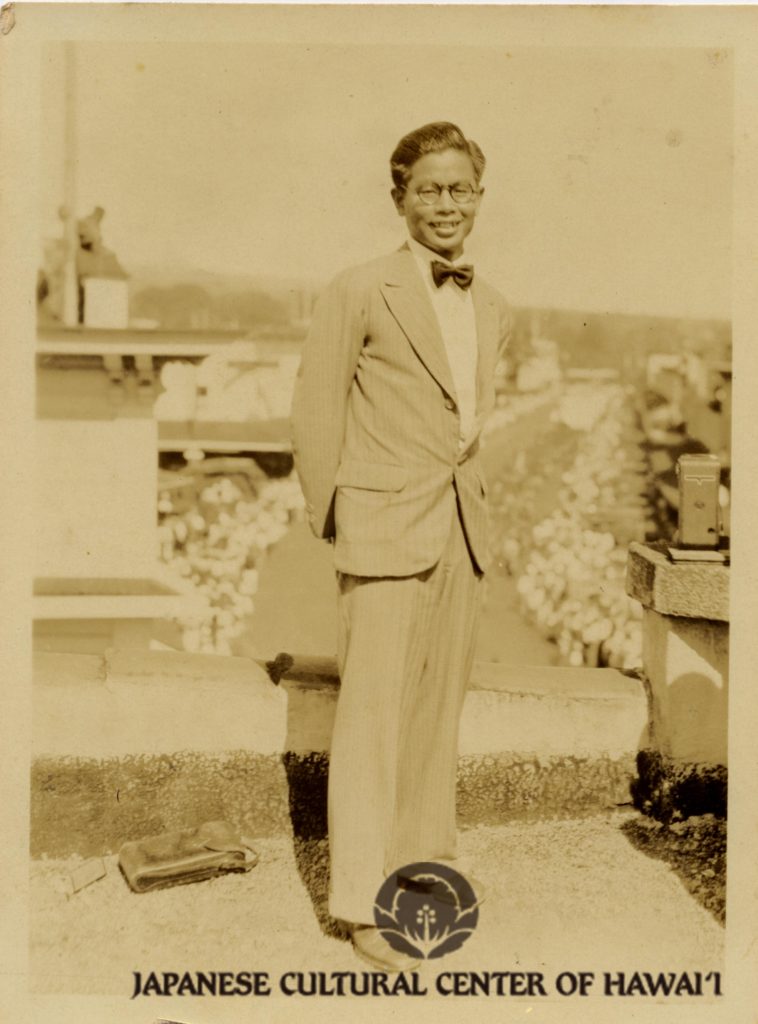

Muin Ozaki (1904-1983):

Like Kagawa, Muin Otokichi Ozaki distinguished himself as a Tule Lake poet after the segregation program. Born in 1904 in Japan (the same year as Kagawa), Ozaki moved with his parents to Hawai`i in 1916. After attending Hilo High School, Ozaki began working for the subscription section of the Hawaii Mainichi. At age 19, he became the youngest member of the newly founded Hilo Tanka Poetry club. Immediately following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the FBI arrested Ozaki and several other Issei leaders. Ozaki was imprisoned in a series of internment camps in Hawai`i and the continental U.S. – Sand Island, Angel Island, Fort Sill, Camp Livingston, and Santa Fe. In March 1944, Ozaki reunited with his family at Jerome concentration camp, and following the loyalty questionnaire was sent with his family to Tule Lake.3

Throughout his internment and incarceration experience, Ozaki authored more than 200 tanka poems that illustrated different aspects of each camp.4 Ozaki wrote his poems on rice paper in order to preserve them during his trips to the different camps. After the war, he returned to Hawai`i and worked for the Hawaii Times. He authored two poetry anthologies, and was featured prominently in the poetry volume Poets Behind Barbed Wire: Tanka Poems.

Tule Lake Internment Camp

(from Poets Behind Barbed Wire, 59)

“fuchusei” to

Kokuin osare

Tule Lake ni

Okurareshi mizo

Kuyuru koto naku

“Disloyal”

With papers so stamped

I am relocated to Tule Lake

But for myself

A clear conscience

Violet de Cristoforo/Kazue Yamane (1917-2007):

One of the more tragic stories from Tule Lake is that of Violet de Cristoforo. Born Kazue Yamane, she grew up in Fresno, California and later married bookshop owner Shigeru Matsuda. In the 1930s, Violet and Shigeru joined a haiku club in Fresno, and soon Violet rose to prominence as a writer of “kaiko,” or free-form haiku. Following Executive Order 9066, Violet, Shigeru, and their two kids were imprisoned in the nearby Fresno Assembly Center. Shortly after recovering from surgery to remove a tumor, Violet gave birth to her third child at the Fresno Assembly Center, where temperatures rose about 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The family was then transferred to Jerome concentration camp in Arkansas. Throughout her time in camp, Violet continued to write poetry with members of her circle.5

In response to the loyalty questionnaire of February 1943, Violet and her family responded “no-no.” While the FBI interned Shigeru at Santa Fe internment camp, the WRA sent Violet and her children to Tule Lake. Violet was caught in the whirlwind of events at Tule Lake that pushed her to renounce her American citizenship. She expatriated to Japan with her children, where, after learning Shigeru left her, she married Army soldier Wilfred de Cristoforo. She returned to the United States, and settled in Salinas, California.6

In her later years, she published several volumes of poetry, based on her poems written while at Tule Lake and later in life. One of her most prominent works was the poetry anthology May Sky: There is Always a Tomorrow. She also emerged as a prominent member of the Redress movement, and became known as a vocal critic of the University of California’s Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement Study and its staff members’ treatment of inmates during the war. In 2007, the National Endowment of the Arts awarded de Cristoforo a National Heritage Fellowship, in recognition of her lifelong contribution to “folk or traditional arts of the United States.”

Untitled poem from May Sky

Orokashisa Tada Ni Natsu No Hi O Kurashi Mukou Castle Rock

Foolishly – simply existing

Summer days

Castle Rock is there

Kenneth Yasuda (1914-2002)

In contrast to de Cristoforo’s story, Kenneth Yasuda emerged as a haiku poet who achieved success in academic circles. A kibei originally from Newcastle, California, Yasuda began his career as a romantic poet while studying at the University of Washington, publishing his poems regularly in the San Francisco newspaper Shin Sekai Asahi Shinbun. (One of his poems from 1940 appeared alongside a poem by Toyo Suyemoto.). In 1941, Yasuda returned to Japan, where he studied haiku under Kyoshi Takahama, the founder of the Japanese haiku magazine Hototogisu. It was there that he developed an affinity for haiku and other traditional Japanese poetic forms. He also became a friend of Yone Noguchi, a writer who had achieved recognition in the U.S. for his English-language poetry.

In 1942, on the eve of completing his studies at UW, Yasuda was imprisoned at Tule Lake. He spent his years at Tule Lake writing poems for the camp newspaper, the Tulean Dispatch. In one issue, he published an essay, written during his time in Japan on the aesthetics of haiku, arguing that haiku emulated the ambiguity found in the paintings of the Impressionist movement. Most of the poems he authored in camp subtly reflected the austere and desolate setting of Tule Lake. Although Yasuda was critical of the U.S. government, he eventually answered “yes-yes” to the loyalty questionnaire and transferred to the Jerome concentration camp.

While at Jerome, Yasuda met Southern poet and Pulitzer Prize winner John Gould Fletcher. A member of the Imagist movement and contemporary of Ezra Pound, Fletcher showed a distinct interest in haiku and Japanese aesthetics. He mentored Yasuda and helped arrange the publication of Yasuda’s haiku study, A Pepper Pod, with Knopf in 1946. Yasuda later published several volumes of haiku, tanka, and Noh plays, and became a prominent scholar of Japanese literature.

“At Denson, Arkansas”

(from A Pepper Pod, 117)

‘Gainst the inky sky

The lightning paints the great oak

As it flashes by.

“At Tule Lake”

(from The Tulean Dispatch Magazine‘s one-year anniversary issue, May 27, 1943)

The rainbow comes once more

To arch the clearing blue,

Bending above this new

City; and there before

Me lies the verdant moor

of lake-bed bathed with dew,

And barracks stand in view

On right side of this tor.

With out-stretched hands I cry

For joy that blooms in seven

Rich colors in a bow.

It holds me rapt, and oh,

My heart leaps to the Heaven,

I almost reach the sky!

—

By Jonathan van Harmelen

Jonathan van Harmelen is a Ph.D candidate in History at UC Santa Cruz. He is currently working as a writer for the Densho Catalyst and encyclopedia with support from UC Santa Cruz’s The Humanities Institute.

Footnotes

1. Stan Yogi, “Japanese American Literature.” From: King-Kok Cheung, An Interethnic Companion to Asian American Literature. (London: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 127; Ishmael Reed, Calafia: the California Poetry. (Berkeley: Y’Bird Press, 1979), 64.

2. Martha Nakagawa, “A Literary Lion.” Rafu Shimpo, December 29, 2014.

3. Ed. Jiro Nakano and Kay Nakano, Poets Behind Barbed Wire (Honolulu: Bamboo Ridge Press, 1983), 5-6.

4. Ibid, 6.

5. Patricia Wakida and Brian Niiya, “Violet Kazue de Cristoforo.” Densho Encyclopedia. Violet Kazue Matsuda de Cristoforo, “There is Always Tomorrow: An Anthology of Wartime Haiku.” Amerasia Journal, 19:1 (1993), 93-115.

6. Ibid.

[Header: Barracks at Tule Lake. Photo courtesy of Toshio Oku Photo Album, Archives & Special Collections, University Library, California State University, Dominguez Hills.]