November 20, 2024

Newspapers have played an important role in informing societies of current affairs and influencing public opinion for centuries, as a primary form of communication and a main source of information before telephones, television, and the internet. Densho recently finished digitizing The Japanese American Courier, a Seattle, Washington newspaper created and edited by James Y. Sakamoto, a prominent figure in the Seattle Nisei community. The Courier ran from January 1, 1928 until April 24, 1942 and had significant influence for Japanese American communities, particularly in Seattle where it kept its audiences apprised of world events, community happenings, sports news, and Japanese American Citizens League activities.

Densho Archives Intern Kathryn Perry Bolin, who worked to digitize the Courier over the past year, looks at how this publication facilitated community building through food for Japanese Americans in pre-war Seattle.

Edith Rauch and the Courier Cooking School

Many interesting topics caught my eye while processing this collection. I considered writing about the Japanese American perspective on international relations or the growing tensions that led to World War II. I also became interested in the many pieces that offered advice about skiing and the “Cinematographs” column which highlighted music, theater, movie, and television trends. However, as I started photographing parts of the collection after 1938, I saw recurring images of a woman I did not recognize who turned out to be Edith Rauch.

Edith was a “domestic science and cookery expert” who led courses at the Courier Cooking School. Hosted by the The Puget Sound Power & Light Company between 1939 and 1941, the Courier Cooking School was a free program that offered classes in modern cooking specializing in American recipes, holiday meal planning, emerging kitchen technology, nutrition, and methods of “beautifying the home.”

It was sometimes referred to as the “Japanese-American courier cooking school” and appealed to multiple generations of Japanese American women. For example, a 1940 article explained that “the increasing number of second generation homes in this community has been noted, and this has increased interest in American dishes.” Similarly, another article titled “Culinary Expert Inspiration for Japanese Women” stated that “recipe experimenters are increasing in the Japanese Community” and explained how the cooking school gave women of all age groups a space to learn about and make new foods.

Edith’s picture was frequently used in advertisements with her endorsements of which markets to shop at, what brands of food to use in cooking, and preference in kitchen appliances. It even encouraged audiences to shop at Japanese businesses for their kitchen and other home-related needs. In 1941, articles about the school addressed rising political and economic concerns about food production and costs, but asserted that the Department of Agriculture was not worried about the nation running out of food and the government instead wanted to raise awareness about having a “better diet for the people in these times of national emergency.”

The paper’s frequent promotion of Edith and the school demonstrated how food could be used as a bridge between Japanese households and American cultural practices. Reflecting Sakamoto’s conviction that Nisei could overcome discrimination by learning “to talk and to act like their fellow Americans,” as well as larger efforts steering Japanese Americans toward assimilation, the school promoted the image of women as homemakers and active members of society. Nevertheless, it also taught women how to strive for a balanced diet and ways to get the most economic value out of food, especially with fears of potential war-time rationing looming.

Local Groceries and Other Advertisements

In addition to Courier Cooking School features, it was also popular to see pastry recipes and advertisements for food promotions, appliances, decorative kitchenware, and local Japanese-owned grocery stores like those seen in the images below.

Cuisine Cues

Today we have the luxury of quickly finding recipes online or going to bookstores and browsing the cookbook section by category, but the Courier reflects a time when people were more dependent on periodical updates, like new recipes to try, from newspapers. Food sharing, as seen in the Courier, is a form of cultural immersion and even acts as a kind of assimilation.

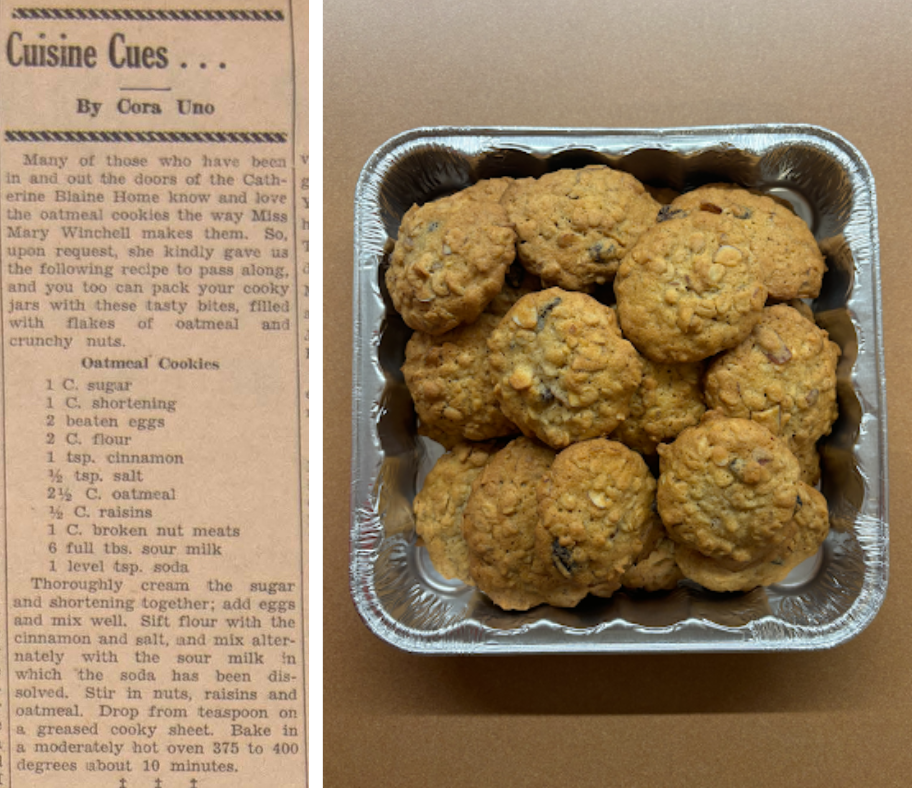

In 1938 and 1939, the Courier featured the “Cuisine Cues” column which provided various dinner and dessert recipes. Recipes could be mailed in for submission by community members and typically included short descriptions about the recipe and tips for improving food quality, bringing out flavor, food substitutions, presentation, side dish recommendations, repurposing leftovers, and storage. Some even had quick fixes for cooking mistakes and other home remedies such as tricks for removing rust, keeping plants healthy, and protecting wooden furniture.

Some recipes sounded familiar, like Banana Bread, Oatmeal Cookies, and Apple Pie. There were plenty I had never heard of, like Almond-Orange Ice Box Cookies or Divinity Fudge, but they sounded delicious. However, I’m not sure I have a taste for the Sour Cream Raisin Pie.

I decided to try out some of these recipes and made the Oatmeal Cookies and the Almond-Orange Ice Box Cookies. I brought them in to Densho to share with staff — you can see how they turned out below.

It was also popular to see a rise in themed dishes around the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays. For example, “Cranberry Nut Salad” and “Stuffing” recipes, as well as short histories of the holidays’ significance, were included in two such editions of the Courier.

The Courier’s coverage of food sharing and domestic life not only promoted dietary balance and practical homemaking but also symbolized broader community sharedness — even as it also encouraged Japanese Americans to leave behind Japanese cultural practices in pursuit of “Americanization.” Eventually, articles focused less and less on food sharing, and more on the rising tensions between the U.S. and Japan. The editors of the Courier promoted loyalty to America in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor up until their last edition in the spring of 1942, when Seattle’s Japanese American community was removed as part of the wartime incarceration.

—

By Kathryn Perry Bolin, Densho Archives Intern

[Header: A cooking class at the Fujin Home, a women’s shelter organized by the Japanese Buddhist Church in Seattle, c. 1920. Courtesy of the Nippon Kan Heritage Association Collection, Densho.]

The work to digitally preserve the Japanese American Courier was supported, in part, by 4Culture/King County Lodging Tax and the Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program of the National Park Service.