June 27, 2017

The drama of the Japanese American exclusion and incarceration has inspired a bewildering number of non-Japanese Americans to write novels that incorporate this experience, with pretty much all portraying the events as a travesty of justice. At least five of these novels have made national best-seller lists; there is little doubt that more people have learned of the World War II removal and incarceration from these novels than from all of the scholarly books put together. Interestingly, two of the authors are of part Chinese ancestry and one is Chilean American. While I think this popular exposure is mostly a good thing, each book does get at least a few things wrong. But despite some historical inaccuracies, it’s easy to see why they were best-sellers (with perhaps one exception): all are fun to read and tell engaging stories.

At the same time, all of the books—with the exception of Danielle Steel’s—mostly tell the story through the perspective of non-Japanese Americans. This points to the need for more novels by Japanese American authors that are written from a Japanese American perspective, such as Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine or David Stewart Ikeda’s What the Scarecrow Said. I’ll be writing about more of these books soon.

But without further ado, here are the best-sellers (ratings are on a scale of 1-5):

Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson (1994)

78 consecutive weeks on the Publishers Weekly trade paperback bestseller list (Oct. 9, 1995 to Apr. 14, 1997) including 37 weeks at #1.

A publishing phenomenon, Snow was about as unlikely a best-seller as one can imagine, a slow-moving murder mystery by an unknown author set on a perpetually dismal island in Washington State (modeled on Bainbridge Island) in the 1950s. The story follows the murder trial of Kabuo Miyamoto, a Nisei accused of killing a fellow fisherman over a land deal gone bad, largely due to the alien land law and the wartime forced removal. The protagonist is newspaperman Ishmael Chambers, who is covering the trial and has never gotten over his childhood romance with a girl who grew up to be Kabuo’s wife. The plot picks up steam in the second half of the book, and the author does a good job of exploring the latent prejudices that lingered on the island a decade after World War II. At the same time, I never really bought the Nisei characters, whose portrayals veer into exotic and inscrutable stereotypes. (Kabuo often plays the stoic, “unreadable” Asian, while his wife, Hatsue, has “the flat-footed gait of a barefoot peasant.”) Though there are a few minor historical miscues, Snow‘s rendering of the roundup and incarceration is generally handled well.

Entertainment value: 4

Historical accuracy: 4

Best/worst gaffe: an Issei woman character came over as a picture bride who was “sold” by her parents into marriage; the Japanese American islanders are rounded up by the WRA and sent first to the Puyallup fairgrounds before being sent to Manzanar. (In reality, the army did the rounding up, and Bainbridge Islanders were sent directly to Manzanar, as the “assembly center” at Puyallup did not open until a month later. The picture bride phenomenon evolved in part as a reaction to restrictive immigration laws and was an extension of Japanese arranged marriage customs; it did not involve the selling of brides.)

Silent Honor by Danielle Steel (1996)

9 consecutive weeks on the hardcover fiction list (Nov. 18, 1996 to Jan. 20, 1997) including two weeks at #1.

9 consecutive weeks on the hardcover fiction list (Nov. 18, 1996 to Jan. 20, 1997) including two weeks at #1.

At the same time that Snow Falling on Cedars was on the trade paperback charts, perpetual best-selling author Danielle Steel’s incarceration saga hit the top of the hardcover charts. The plot involves a young Japanese college student named Hiroko Takashima who comes to stay with Japanese American relatives in the San Francisco Bay Area. The family she stays with is headed by an Issei professor at Stanford (perhaps modeled after Yamato Ichihashi), and inevitably, romance develops between Hiroko and a young white professor who is a friend and colleague of the family head. Since it is 1941, their romance is interrupted by war, the Nikkei family forcibly incarcerated, the young professor sent off to war in Europe. Both far-fetched and predictable, the story gets dull quickly. While Steel’s account is certainly sympathetic to Japanese Americans, there are many errors in the portrayal of the incarceration, including such common ones as exaggerating conditions in the camps (inmates are described as having to shovel out “two feet of manure” for their horse stall dwelling at Tanforan), getting the timing of events wrong (an inmate who volunteers for the 442nd is killed in action on New Year’s Day, 1944, five months prior to the first such death of a volunteer from the concentration camps), and having inmates go to the wrong camps (while nearly all those from Tanforan were sent to Topaz, the characters here go from Tanforan to Tule Lake and Manzanar). Though only a modest success by Steel’s standards, Honor had sold a staggering four million copies by the end of 1997.

Entertainment value: 2

Historical accuracy: 2

Best/worst gaffe: upon leaving Tanforan, the family is separated and two family members are taken to a different camp—later revealed to be a separate area of Tule Lake—where they are harshly interrogated for a week before being allowed to rejoin the rest of the family. This is pure invention.

Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet by Jamie Ford (2008)

Three weeks on the hardcover fiction bestsellers list, with a peak of #9 on April 6, 2008.

Another unlikely best-seller, Hotel uses the common device of events in the book’s present (1986 in this case) causing characters to go back in history to recall the war years. In this case, the protagonist is Henry Lee, a recently widowed Chinese American man, who recalls his romance with a Nisei girl when both were just twelve and her subsequent forced removal and incarceration that breaks it up. Though the story is hokey and unlikely—how many twelve-years-olds do you know who go on dates at jazz clubs?—I actually got caught up in the story once I suspended my disbelief. There are no major historical issues here, but many small ones, including more time shifting (e.g. the shelling of a Santa Barbara, California, refinery takes place after the eviction of Bainbridge Island Japanese Americans rather than a month prior as it did in real life; all Japanese in Seattle are removed on the same day in the book, whereas this took place over the course of about two weeks in actuality).

Entertainment value: 5

Historical accuracy: 4

Best/worst gaffe: placing an internment camp in Nevada (there was none); a fatal shooting in Minidoka in the fall of 1942 that never happened.

China Dolls by Lisa See (2014)

Five weeks on the hardcover fiction bestseller list, with a peak of #12 on June 9–15, 2014.

An entertaining story about performers at Chinese themed nightclubs in San Francisco and New York from 1938 to 1948, China Dolls focuses on three women whose friendships wax and wane over the decade. These real life nightclubs—the most famous of which is probably Charlie Low’s Forbidden City in San Francisco—make a great setting for a historical novel. One of the three main characters—Ruby Tom—turns out to be a Nisei masquerading as “Chinese,” and she evades the removal and incarceration for a time. See based Ruby on actual Nisei performers Dorothy Toy and Trudy Long, though Ruby’s ability to dodge incarceration for a full year while a famous entertainer is a bit far-fetched. This is nonetheless my favorite book of this group, whose portrayal of the obstacles Asian American career women faced in that time period ring true. The history is also generally handled well.

Entertainment value: 5

Historical accuracy: 4

Best/worst gaffe: Ruby’s parents spend the war years into 1946 interned at the Leupp, Arizona detention camp. A camp used to imprison dissidents from the main WRA camps, Leupp was not an internment camp and was only in existence for around seven months in 1943.

The Japanese Lover by Isabel Allende (2015)

Three weeks on the hardcover fiction bestsellers list, with a peak of #11 on Nov. 9–15, 2015.

Could this be the first fictional work that features a Nisei man as sex object? Again, events in the present trigger flashbacks to the past, as a wealthy widow named Alma Belasco arrives at a hip retirement home in Northern California. As we delve into her mysterious past, the role of her childhood friend—the Nisei son of the family’s Japanese gardener—comes into focus, revealing their decades long love affair that is inevitably shaped by the wartime incarceration. It’s a colorful and entertaining story, though the Nisei character—Ichimei Fukuda—is a bit of an exoticized cypher whom we never really get to know. (And the names! Ichimei’s mother is named “Heideko.” Allende must have been inspired by Guterson’s “Kabuo” Miyamoto from Snow.) There are also a lot of historical liberties taken here: more exaggeration of conditions in the camps—lines for the latrines that “stretched for several blocks”; letters from Ichimei to Alma that are routinely censored (this only took place at army or INS run internment camps)—along with a misunderstanding of the “no-no” phenomenon. Allende is a good storyteller, though, so I enjoyed the book despite these issues.

Entertainment value: 5

Historical accuracy: 2

Best/worst gaffe: despite leaving camp at the end of 1945, the Fukudas are deposited in Arizona because they are not allowed to return to San Francisco. But restrictions on Japanese Americans returning to the West Coast had been lifted at the end of 1944, so the Fukudas would have been free to return to California by the beginning of 1945.

—

By Densho Content Director Brian Niiya

Snow Falling on Cedars published by Vintage Books.

Silent Honor published by Dell Publishing.

Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet published by Ballantine Books.

China Dolls published by Random House.

The Japanese Lover published by Atria Books.

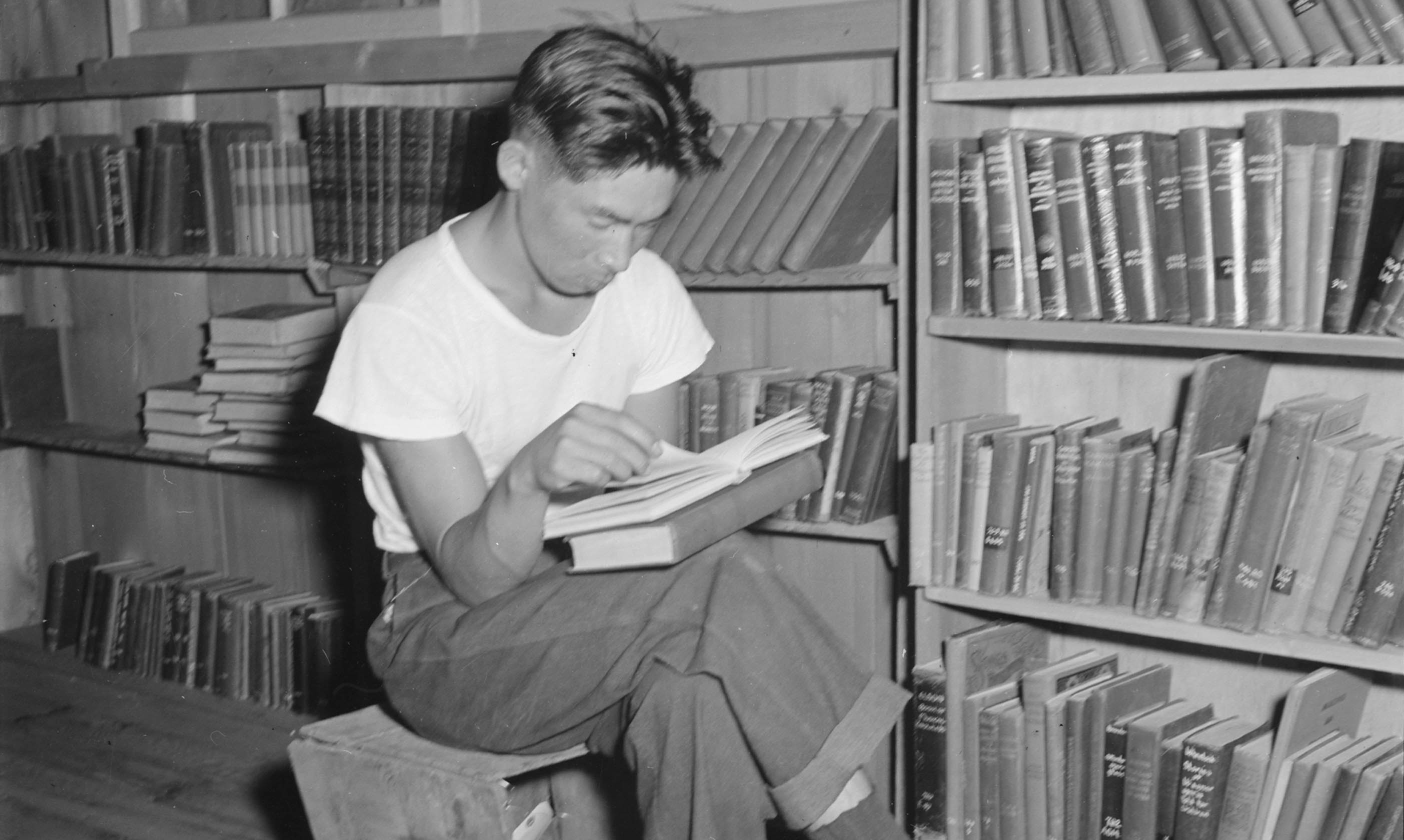

[Header photo: Japanese American reading in library at Manzanar. July 1, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]