April 30, 2015

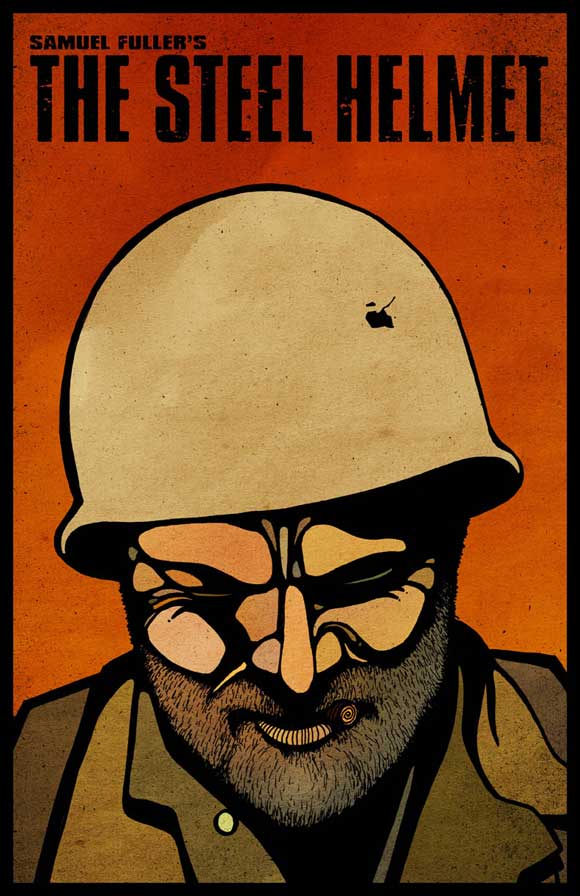

The Steel Helmet—a 1951, low-budget film by Samuel Fuller—features one of the first popular culture references to Japanese American incarceration. In this post, Densho Content Director Brian Niiya presents a film history and analysis.

I’ve been a big fan of the acclaimed B-movie director Samuel Fuller since seeing his 1960s films Shock Corridor and The Naked Kiss many years ago. I became an even bigger fan after seeing his remarkable The Crimson Kimono (1959), a murder mystery/love story starring James Shigeta as an LA cop and set in Little Tokyo during Nisei Week. His movies tackle provocative themes and often feature interracial casts; as B-movies, they also follow genre conventions in being fast moving, action packed and sometimes crass and exploitative as well. They are never dull.

He was also something of an Asia-phile with no less than four of his movies either set in Asia or Asian America. Besides Crimson Kimono, there was House of Bamboo (1955), set in occupied Japan and starring “Shirley Yamaguchi” (aka Ri Koran and Yoshiko Otaka); China Gate (1957), the first Hollywood film set in Vietnam; and the subject of this essay, The Steel Helmet (1951), the first Hollywood film to depict the Korean War.

(I’m also fascinated by Yamaguchi, whose various incarnations include Nisei pin-up girl, superstar singer, Japanese propagandist in occupied China, wife of Isamu Noguchi (and with him, part of the model “Nisei” couple), American movie star; and postwar Japanese politician, among other things. But we’ll leave her for another time.)

Samuel Fuller was born in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1912 and moved to New York with his family after his father died when he was eleven. As a young teenager, he began to sell newspapers, which led to his becoming a copy boy, then a crime reporter for the New York Evening Graphic, a notorious scandal sheet, at age 17. Intrigued by California, he headed west in the mid 1930s and eventually broke into Hollywood ghostwriting screenplays for established screenwriters. After serving in World War II—including landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day—he established himself as a screenwriter in Hollywood under his own name. Independent producer Robert Lippert gave him a chance to direct his own screenplays in 1948, beginning with I Shot Jesse James.

The Steel Helmet was his third movie for Lippert and proved to be a turning point for his career. As with his other early movies, it was shot quickly and on a low budget, with Griffith Park in Los Angeles standing in for Korea. Filmed over the course of ten days in October of 1950, the movie’s budget was just $104,000.

The movie centers on a grizzled World War II veteran named Zack, played by newcomer Gene Evans. As the movie begins, he is the lone survivor when his platoon is slaughtered by the enemy; shot in the head, the bullet pierced his helmet but rattled around inside, leaving him unharmed. He is discovered and unbound by a South Korean orphan boy (William Chun) of around twelve who follows him despite Zack’s discouragement. The pair come across another lone soldier, an African American medic, before coming across a lost unit assigned to set up a surveillance post in a Buddhist temple. The group eventually finds the temple and a lone North Korean soldier is discovered in it after he kills one of the Americans. When the boy—whom Zack and men become attached to despite themselves—is shot by an attacker, the captured soldier—now a potentially valuable POW—makes a sarcastic remark about a note the boy had written wishing he could get Zack to like him. Zack impetuously shoots and kills the prisoner. The soldiers subsequently repel an enemy attack, though only four survive.

It is a familiar trope in war movies, westerns, and other genres: the diverse group of misfits and survivors thrown together by chance who overcome their personal differences to band together and successfully achieve their mission. The group here is particularly diverse; as one contemporary reviewer sardonically observed, “… the infantry has assembled in brotherhood a group of men representing every American type except the anti-vivisectionist.”

Two are racial minorities: Corporal Thompson, the African American medic played by James Edwards, and Sergeant Tanaka, a Nisei character played by Richard Loo. (Loo, a Chinese American actor born in Maui, was best known for playing Japanese enemy figures in movies during and about World War II and had a role in the infamous Little Tokyo U.S.A.) Both are portrayed as exceedingly competent and cool under fire in contrast to many of the other men. As a seasoned World War II vet like Zack, Tanaka stoically repels a sniper attack while the other men run for cover. Later, when a cowardly lieutenant accidentally pulls the pin from a grenade and panics, Tanaka cooly resets it.

Both are also targeted by the Communist POW played by Harold Fong. When guarded by each, the POW points out the discrimination each faces in the U.S. in the attempt to covert them to his side or at least to discourage them. The dialogue with Tanaka is worth quoting in full:

POW: You got the same kind of eyes I have.

Tanaka: I’ve got some hot infantry news for you: I’m not a dirty Jap rat, I’m an American, and if we get pushed around back home, well that’s our business. But we don’t like it when we get pushed around by… ah, knock off before I forget the articles of war and slap those rabbit teeth of yours out one at a time.

This is likely the first disapproving mention of Japanese American incarceration in a mainstream movie and comes in the context of the rapidly changing mainstream portrayal of Japanese Americans that took place in the decade after the end of World War II. The Steel Helmet wouldn’t even be the only mainstream movie released that year to portray Japanese Americans in a positive light: just a few months later, Go for Broke!, which centers on the exploits of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, would be released.

There are many reasons for the rapidly changing view of Japanese Americans during this time period, but the setting of The Steel Helmet highlights one of the main ones: the Cold War/anti-Communist tenor of the times. In the battle for the hearts and minds of the Third World, racial discrimination undermined the Western cause. The patriotic war veteran Fuller portrayed an American military united across racial lines that comes together to achieve their mission. But unlike many others, he is also willing to point out the racism that still infected American society, explicitly and literally illustrating how it could be used by the enemy to criticize the American way and maybe even to disrupt American unity.

The film opened on January 11, 1951 and there were two somewhat unexpected outcomes. One is that some observers—most notably the anti-Communist New York Daily Mirror columnist Victor Riesel—accused the film and the proudly patriotic Fuller of promoting Communism. In interviews and in his autobiography, Fuller recounts being called to the Pentagon and grilled over the content of his film. The key objections were that the soldiers were not portrayed in a heroic fashion—many were portrayed as cowardly or incompetent—that the main character shoots the POW and goes unpunished for doing so, and that U.S. racial discrimination is criticized. The other is that the low budget film was a substantial financial success. Because Fuller worked for a share of the profits, the film ended up making him a wealthy man (in his autobiography, he reports clearing $2 million after taxes), which no doubt contributed to his ability to keep making idiosyncratic and personal films for the next two decades.

As for Sergeant Tanaka, we know he survives the movie, but we don’t know much else about him or his background—we don’t even know his first name—except that he or his family went to camp and that he presumably served in the 442nd. But we can credit him with being one of the first to expose America’s concentration camps and the exploits of Nisei soldiers to movie audiences, and for that, he should be remembered.