May 10, 2019

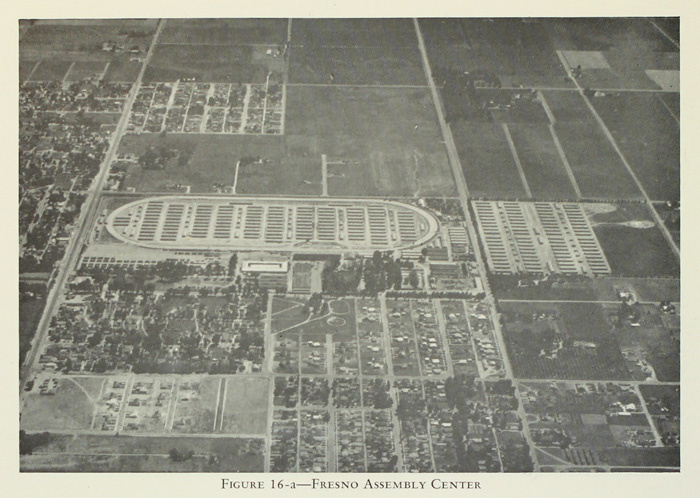

The Fresno Assembly Center* (FAC) opened on May 6, 1942 and held a total of 5,344 Japanese Americans forcibly removed from the Fresno and Sacramento areas. One of fifteen dedicated short-term detention camps opened in the spring of 1942, the facility closed six months later when the population was transferred to a more permanent prison camp in Arkansas. Though surrounded by barbed wire fences and guarded by military police—all the while facing oppressive heat in a nearly shadeless camp and a nightly curfew and roll call—Fresno inmates did their best to make the best of things. We’ve put together a list of some of these FAC facts of life and stories of making do.

1. One of the Longest Running “Assembly Centers”

Fresno was one of the longest running of the “assembly centers,” and the last to close. It was open for a total of 177 days—from May 6 to October 30, 1942. This had a number of impacts, including a more substantive newspaper and educational programs, which will be further explored below. One somewhat ironic impact is that Fresno inmates were sent to clean up two other assembly center sites upon their closings. At the end of July, sixty to eighty were dispatched to Pinedale, some working there for over a week. A work crew was also sent to Tulare in early September for a day.

2. To Jerome and Back

Essentially the entire population of the Fresno Assembly Center moved on to the Jerome, Arkansas, concentration camp in October of 1942, with the last group leaving on October 30. One group of about 150 tuberculosis patients and their families were sent to Gila River instead, with the rationale that the desert conditions would be better for such patients.

Nearly all Japanese Americans in Fresno County were sent to the FAC, and these Fresnans made up about half of the population of FAC. While a little over half of all Japanese Americans in WRA camps returned to the West Coast upon their release, nearly 95% of those from Fresno County returned there upon their release—the highest figure of any county in California.

3. Block Parties on Butler Avenue

Fresno was built on the 160 acre Fresno County Fairgrounds and was bisected by Butler Avenue, which was closed off while the camp was in operation. Six of the ten blocks of barracks were north of Butler, in the racetrack area of the grounds, while four, along with an outdoor recreational area, were south of Butler.

Butler became a gathering place for inmates, especially on hot summer days, since it had the only trees to be found in the camp. In a 2010 Densho interview, Kenji Maruko recalled that “on Saturday nights, the fire department would wash down the street, and then they’d have social dancing at night.”

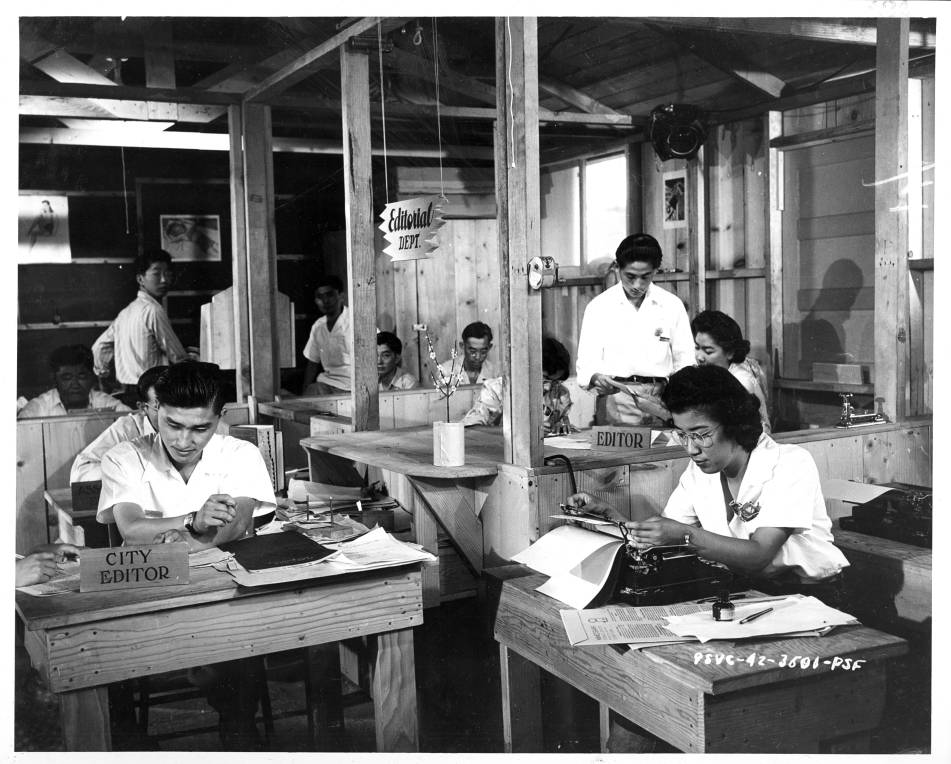

4. Ellen Noguchi and the Fresno Grapevine

Given the FAC’s relatively long lifespan, it is no surprise that the Fresno Grapevine newspaper had one of the longest runs of any assembly center paper—forty-four issues. In addition to the twice weekly newspaper, Grapevine staff members also printed various forms and announcements for the administration, and produced a one-hundred-page yearbook titled Vignette upon the camp’s closing. As with other camp newspapers, the Grapevine was subject to censorship by camp administrators and had a mostly compliant Nisei staff, many of whom had ties to the Japanese American Citizens League.

The staff was also a stable one and was led by a young Nisei woman. Twenty-two-year-old Ellen Ayako Noguchi (1919–2000) was born in Tulare and had contributed to the Rafu Shimpo and Nichibei Shimbun newspapers before the war and had been a member of the Tulare County JACL. She was sent to Jerome, Arkansas, and also worked on the newspaper there, serving as the features editor, and was also one of the leaders of an active Young Buddhists Association (YBA) group there. She later ended up in Seabrook Farms, after marrying Kiyomi Nakamara of Fowler at Jerome in 1944, and leaving for New Jersey later that year. Seabrook Farms became a popular destination for Japanese Americans leaving the concentration camps, and Ellen ended up working there as a public relations person for nearly forty years. A leader of the Japanese American community there, she was one of the founders and initial chair of the Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center, which opened in Oct. 1994.

5. Don’t Sit on the Last Seat

As was the case with several other Central California assembly centers, Fresno’s latrines consisted of a wood bench with holes cut into them suspended over a tin trough. Every few minutes, a can would tip, “flushing” the trough. Many inmates recalled that whomever was sitting in the last seat would have to be careful to avoid getting splashed by the sewage filled water when the “flush” took place. The toilets were initially unpartitioned, but partitions were added later after much inmate objection. There were no doors or curtains in the front. Inmate complaints also let to the addition of toilet seats over the holes in the bench.

6. A Mass Food Poisoning Incident

On May 20, 1942, as the last inmates were arriving, some three hundred people eating at the same mess hall were stricken with food poisoning, overwhelming the camp’s medical facilities. In a 1980 oral history, Kikuo Taira, one of the camp physicians, blamed the inexperienced cooks and inadequate refrigeration, which resulted in their “leaving food out in a hundred something temperature…. Well, anyway, people ate that and got sicker than heck. Thought some were going to die.”

7. The Only WCCA Agricultural Program?

While all of the War Relocation Authority administered camps had agricultural programs in which inmates grew some of their own food, such programs were mostly absent in the Wartime Civil Control Administration “assembly centers,” both because many of the existing facilities didn’t have available land and because Japanese American inmates remained in these camps for such a short time. Perhaps alone among assembly centers, Fresno had an agricultural program that grew squash, radishes, and string beans that were distributed to camp mess halls in September.

8. Stealing Food

In an August 23, 1942 letter, Fresno inmate Minnie Umeda wrote that the camp had “no sugar, so they use syrup instead of sugar in the coffee and grapefruit without sugar and dinner is particularly always wenies (sic) and cabbage so I am getting tired of it.” Four days later, a chef at Fresno, Walter B. Lewis, was arrested by the FBI on allegations that he had been stealing food stuffs meant for the mess halls. His bail was set at $500.

9. Art Teacher and Chronicler Henry Sugimoto

One of those who taught at Jerome was the Issei artist Henry Sugimoto (1900–1990). Already well known as an artist, Sugimoto was living in Hanford, California, with his family when the war began. Because he taught at a Japanese language school, he was fearful he would be arrested and interned. Spared that fate, he was nonetheless caught up in the mass forced removal of Japanese Americans, and ended up at Fresno with his family. In addition to teaching art there, he also took it upon himself to document the removal and incarceration experience, having brought some art supplies with him. Holed up in his barracks unit, he painted images of the roundup of Japanese Americans as well as images of life at Fresno. He continued to document concentration camp life in drawings and paintings at the Jerome, Arkansas camp, and, after that camp closed in June 1944, at the neighboring Rohwer, Arkansas, camp. He settled in New York after the war, where he lived for the rest of his life. His camp era paintings have appeared in numerous exhibitions and publications about the removal and incarceration, and his work was featured in a retrospective exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum in 2000.

10. Inez Nagai and the FAC Education Program

Due in part to its long lifespan, Fresno had one of the more extensive educational programs among assembly centers, with both a summer school program and an ambitious fall program in the camp’s last weeks. The summer program began at the end of May when an inmate education committee formed and put together a school program in consultation with the administration. Inez Nagai became the inmate education head. Eventually, thirty inmate teachers were hired. Making do with a lack of supplies and classroom space—recreation halls were used for classes and some classes even met outside—along with discarded school books donated by the Fresno City Schools, classes for children and adults were held. A group of Girl Scouts also ran a nursery school. There were also adult classes; among the teachers were Mary Tsukamoto, who taught public speaking to high schoolers and English to adults, and Henry Sugimoto, who taught art classes. Later, classes in such topics as wood carving and business law were added to the adult program. Some 1,600 children and adults took part in the summer school program. The summer school program ended on August 29.

After a three-week break, mandatory fall classes for elementary students began on September 21. About 850 enrolled. A warehouse building in Block G was converted into a school building with “a large assembly room and four separate classrooms.” In combination with preschool and adult students, a total of 2,005 people enrolled in the fall educational program.

Nagai (1915–2009), who was born in Tulare, was the first Nisei to become a schoolteacher in California, having been a PE teacher at Edison Junior High in Fresno prior to the war. After leaving Fresno Assembly Center, she worked as a PE instructor at Jerome before resettling in Madison, where she had previously done some graduate study at the University of Wisconsin and where she eventually graduated with a master’s degree in dance in 1944. Moving to Chicago, she taught the YWCA and the University of Chicago and coached water shows at Stephens College in Missouri in 1952. Returning to California in 1952, she taught at Carlmont High School in Belmont and became head of the PE Department in 1953. She later moved to Menlo-Ahterton High School in 1965 and coached drill and swimming teams. She retired in 1981 after a forty-year teaching career.

—

By Brian Niiya, Densho Content Director

*Although we use the term “assembly center” to differentiate between temporary detention sites like FAC and more permanent sites like Jerome concentration camp, it should be noted that this terminology is clearly euphemistic in nature, as the “assembly” was carried out by military and political force. We use this term only as part of a proper noun (e.g. “Fresno Assembly Center”) or in quotation marks for specific references to this type of facility. (Read more: https://densho.org/terminology/)

The information presented here has been excerpted from Densho’s new and improved Sites of Shame project, coming to a device near you in 2020. Full citations will be included there, but feel free to post questions in the comments or email us at info@densho.org in the meantime!

[Header photo: The editorial offices of the Fresno Grapevine, 1942. Courtesy of San Jose State University, Flaherty Collection.