August 20, 2025

This month, we commemorate the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, marking a pivotal moment in U.S. history in which the government offered redress and reparations for the forced displacement and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Yet we also remember the decades of community activism and organizing that made reparations a reality. Use these Densho resources to explore crucial lessons of the Japanese American Redress Movement and its important place within the larger WWII incarceration narrative.

Historical Background

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was signed into law on August 10, 1988, by President Ronald Reagan. The Act granted wartime survivors a formal presidential apology and individual reparations of $20,000, in addition to creating a public education fund. This law not only publicly and legally acknowledged the injustice of the wartime incarceration, but it also transformed how this history would be remembered, discussed, and taught for generations to come.

Overturning past claims of “military necessity,” the Civil Liberties Act attributed the forced removal and incarceration of over 125,000 people of Japanese descent to “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria and a lack of political leadership.” This language—now commonly used to describe this historical event—derived from the findings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), a body appointed by Congress in 1980 to research and suggest remedies for the incarceration.

The CWRIC’s recommendations, published in 1983 after conducting hearings in 20 cities with testimonies from more than 750 witnesses, provided factual and emotional support for monetary reparations. However, the battle to implement the CWRIC’s findings and provide reparations was fought hard among Congressional committees and lobbyists. A combination of Japanese American legislators, a coalition of community groups, and House Democratic leaders helped secure the bill’s passage with few amendments.

But the CWRIC would not have existed, nor would the 1988 Civil Liberties Act have been passed, if not for the decades-long social activism and organizing of the Japanese American community. These community leaders and activists were at the heart of the Redress Movement, which gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s, drawing inspiration from other civil rights, anti-war, and ethnic pride movements occurring at that time.

The Redress Movement was shaped by the leadership of three major organizations, each with distinct philosophies and strategies. The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), the longest-standing national Japanese American organization, pursued a pragmatic, legislative path to redress, lobbying members of Congress and supporting the creation of a federal commission to study the wartime incarceration. The National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR), which formed in 1979, took a more confrontational legal approach, filing a class action lawsuit against the U.S. government seeking $27 billion in reparations for constitutional violations.

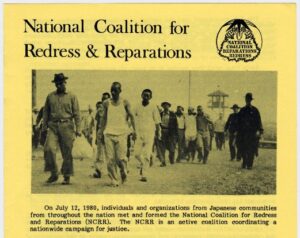

Meanwhile, the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR), which formed in 1980 and was led primarily by Sansei activists, used a grassroots organizing approach—influenced by Third World Solidarity and civil rights movements—to demand individual monetary reparations and a formal government apology. NCRR helped mobilize the Japanese American community to speak out at the CWRIC hearings, amplifying survivor voices and centering the incarceration experience within a wider critique of state racism and violence.

Together, these organizations advanced the Redress Movement, weaving together legal challenges, congressional lobbying, and grassroots organizing to secure the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Their work demonstrates how Japanese American redress was both a result of internal community work and a broader movement for racial justice, self-determination, and state accountability.

Why Learning about the Redress Movement Is Important

Learning about the Redress Movement is essential for telling a fuller, more complex story of the Japanese American incarceration and its aftermath. Too often, the incarceration is remembered only as a tragic episode of mass removal and imprisonment, with little attention paid to the postwar period. By expanding the narrative scope, we recognize not just the wartime injustices inflicted by the government, but also the long-lasting consequences of incarceration, from the challenges of resettlement to intergenerational trauma. At the same time, we also see how Japanese Americans mobilized in response—how survivors and descendants turned pain into action, challenging state narratives and demanding justice.

The Redress Movement highlights powerful stories of resistance, resilience, and community organizing that complicate and enrich the incarceration narrative. Activists and survivors challenged government denial, built coalitions, and insisted on the recognition of constitutional violations that had once been justified as wartime necessity. By remembering Redress as part of the incarceration story, we honor the legacy of those who fought for justice and ensure that this history is not reduced to victimization alone, but also remembered as an example of collective strength and civic engagement that continues to inspire social movements today.

Long-time NCRR members June Hibino, Richard Katsuda, and Janice Yen describe in their own words the importance of learning about the Redress Movement. We offer their remarks below, alongside other Densho resources, for learning about the history and legacy of Japanese American Redress.

“It is important to learn the history of JA Redress because the 10-year campaign for redress proved that even a relatively small community that is united behind an undeniable truth, that persists through many ups and downs, and that reaches out for broad support, can win a major victory – one that at the outset seemed almost impossible to achieve.” – June Hibino

“Teaching about the Japanese American Redress Movement is critical toward understanding and appreciating that, as devastating and enduring as the impact of the WWII incarceration was on the Japanese American community and its 125,000 individuals with distinct life stories of suffering, the community fought courageously to win back their dignity and to finally place the burden of guilt that they had shouldered for 40 years onto the U.S. government. That movement has united and made whole the community that had been so terribly fractured during and after the war.” – Richard Katsuda

“The incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II must be told in our schools and as part of U.S. World War II history. So many people are unaware of the great injustice done to Japanese Americans, and even fewer know that there was a successful 10-year redress movement to obtain meaningful reparations conducted by the community and supported widely by justice minded Americans.” – Janice Yen

Resources for Learning about the Redress Movement

Milestones of the Movement

The path to the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was laid by pivotal acts that galvanized the Japanese American community and captured public attention. These moments—from solemn remembrances to powerful public hearings—were crucial in transforming the fight for redress into a national cause.

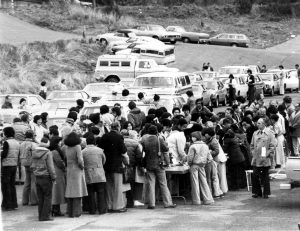

The First Day of Remembrance, Thanksgiving Weekend 1978:

Learn how a miles-long caravan of cars traveled from Seattle to the Puyallup Fairgrounds, retracing a path of expulsion to reignite the Redress Movement. This article by Frank Abe, one of the event organizers, recounts how an unprecedented show of support for a Day of Remembrance revitalized the movement at a precarious point.

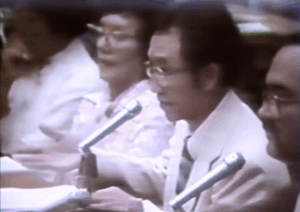

Japanese Americans Demand Justice “Long Overdue” at 1981 Redress Hearings:

This photo essay captures the emotionally charged atmosphere of the Redress hearings in 1981. Here, hundreds of Japanese Americans broke decades of silence to testify publicly about the trauma of their wartime experiences.

Justice Now! Reparations Now! Film:

This documentary film shows the contributions of the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR) during the movement, outlining the group’s “grass roots” orientation. The film includes footage from the Los Angeles CWRIC hearings, which NCRR helped to organize. See more footage of the LA hearings on Visual Communications’ website.

Women Who Championed Redress

From courtrooms to community orgs, the labor and leadership of women was essential to the Redress Movement. These resources highlight the often-overlooked stories of women who organized, strategized, and fought for the cause.

The Nisei Women Who Fought—and Won—an Early Redress Battle in Seattle:

Four decades after being forced to resign in 1942, twenty-seven Nisei women demanded justice from the Seattle School Board. Their unexpected victory foreshadowed the success of the larger Japanese American Redress Movement.

A Conversation with Kathy Masaoka:

In an exclusive interview with Densho, Kathy Masaoka—a key Redress organizer—offers insight into the energy, work, and perspective that women brought to the movement.

The Women Who Led the Fight to Overturn the WWII Supreme Court Japanaese American Incarceration Cases:

Read the words of Lorraine Bannai, a member of the legal team that overturned Fred Korematsu’s conviction for his wartime civil disobedience, as she highlights the monumental, yet often overlooked, contributions of Japanese American women to critical cases that challenged the basis for incarceration.

Voices of Redress: Oral Histories

At its core, the momentum of Redress relied on individual stories. By listening to those who lived through incarceration and the subsequent fight for justice, we can better connect with these historical events. These oral histories allow us to hear directly from movement leaders and everyday participants about what the battle for redress entailed.

Watch this curated YouTube playlist for a selection of narrators who describe the community’s efforts, the impact of testifying, and personal reflections on receiving a federal apology and reparations.

Hear from Rae Takekawa, who describes the bittersweet feeling of receiving redress after her mother, who also endured the camps, had already passed away.

Listen to May Sasaki explain why the official apology was more important to her than the monetary payment, and why passing redress was vital for future generations.

Organizational and Grassroots Records

These collections provide primary source materials from both institutional and grassroots efforts involved in the Redress Movement.

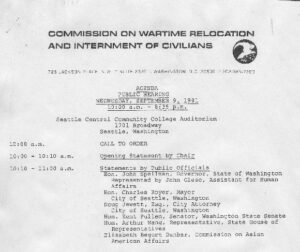

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians Collection:

Browse through a selection of papers and powerful written testimonies submitted to the congressional commission that formally investigated the incarceration.

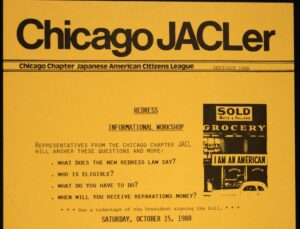

Chicago Chapter JACL: Redress Activities:

Peruse documents that give insights into the grassroots organizing and lobbying that fueled the Redress Movement. This collection contains a breadth of items, from fundraising materials to correspondences with community and congressional leaders.

Kinoshita Collection:

Follow the arc of the movement, from early efforts like the “Seattle Plan” and the campaign to compensate Seattle Public Schools clerks fired after Pearl Harbor, to the signing ceremony for the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

Personal Papers and Family Histories

Reflect on the struggle for justice through the detailed records of individuals and families who contributed to the movement.

Frank Abe Collection:

Explore the work of activist and author Frank Abe, whose collection includes a wealth of oral history interviews, research materials, and documents covering key milestones like the first Days of Remembrance and Gordon Hirabayashi’s appeal of his wartime conviction.

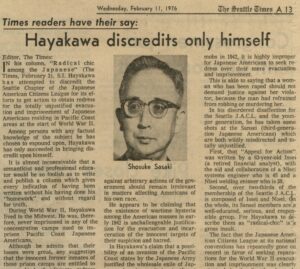

Shosuke Sasaki Collection:

An Issei who was incarcerated in Minidoka during WWII, Shosuke Sasaki played a prominent role in forming the “Seattle Plan” for redress in the early 1970s. His collection includes various op-eds, letters, and National Council for Japanese American Redress newsletters that show some of the internal tensions within the Japanese American community around the issue of redress and reparations.

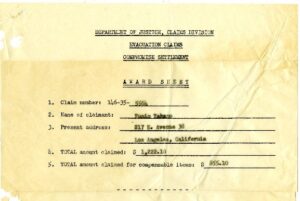

CSU Dominguez Hills Takano Family Papers:

This collection contains papers documenting the Takano family’s pre-war lives, their forced removal, wartime incarceration, and involvement in the Redress Movement. Importantly, it highlights the family’s attempts to recover economic losses through the frustrating and largely unsuccessful Evacuation Claims Act of 1946.

—

Written and edited by Haeley Christensen, Densho volunteer; Jennifer Noji, Densho Development & Communications Manager; and Nina Wallace, Densho Media & Outreach Manager.

[Header: Japanese Americans testify at the CWRIC hearings in Los Angeles, 1981. Courtesy of the Paul Bannai Collection, Densho.]