March 4, 2022

Last month we joined our community in a flurry of Day of Remembrance events to mark the 80th anniversary of Executive Order 9066. After some thought-provoking discussions about why this history matters today and a rally to “Remember and Resist” with Tsuru for Solidarity, La Resistencia, Minidoka Pilgrimage Planning Committee, and local chapters of the JACL, we hurried back to the Densho office to unveil our new Memory Net Remembrance Project.

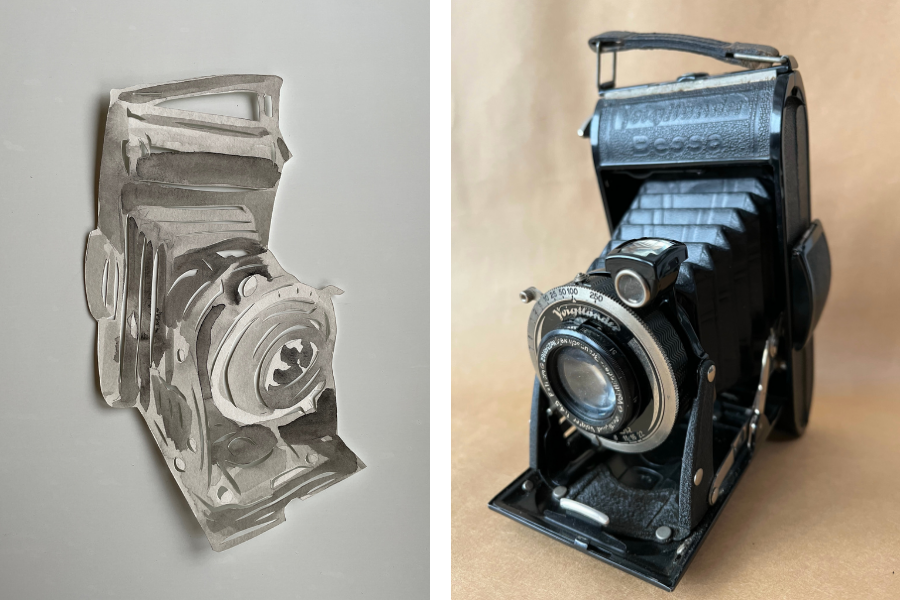

In collaboration with Densho resident artist Lauren Iida, we invited community submissions of “memory objects” that symbolize hope, strength, and resistance during Japanese American WWII incarceration. We received some amazing submissions, each with their own unique story. Lauren selected from these objects to create a 30-foot-long cut paper Memory Net that will remain on display in Densho’s community room for the foreseeable future.

Lauren joined Densho Communications & Public Engagement Director Natasha Varner and poet Lane Tomosumi Shigihara for a virtual conversation about the Memory Net Remembrance Project and the stories behind it.

We’ll be adding photos and descriptions of the remaining memory objects to a special collection in the Densho Digital Repository soon, and plan to host an in-person viewing of the Memory Net when it is safe to do so. Stay tuned for more!

For now, watch that conversation and the virtual unveiling of this project below, then scroll down to learn more about some of the memory objects submitted by the Densho community.

The Memory Net

The Stories Behind the Objects

In 2015, Sarah Yomogi Sato was the first former internee to receive an honorary high school diploma from the State of Hawai`i. Her grandson, Lane Tomosumi Shigihara, submitted her diploma as a memory object:

“My Sansei maternal grandmother’s high school education was cut short during WWII. During her junior year at President William McKinley High School, Sarah Yomogi Okada Sato and her family were sent from Honolulu to the Jerome Relocation Center. Because she and her father refused to answer “yes” or “no” in the US government loyalty questionnaires and instead wrote, “Give me a reason for our internment” to Question 27, and for Question 28 wrote, “I will answer 28 after getting an answer for 27,” her family was then incarcerated at Tule Lake Relocation Center. Her strong-will, love, and devotion to her ohana throughout a time of social injustice embolden me to share her stories with the next generation.“

Sarah Escobido Brandenstein describes these “sunflowers growing in the desert of Topaz as remembered by my Great-Aunt: Bright, tall, towering sunflowers. Huge blossoms reaching into the sky, escaping the confines of the concentration camp’s barbed wire fences. The sunflowers blessed the landscape with vibrant green leaves and joyful beautiful flowers that nurtured my Grandmother and Great-Aunt.

“My Great-Aunt May Takashima remembers her and my grandmother Tomiko Saito playing in the shade of the giant sunflowers that were planted by incarcerated Nikkei in Topaz Camp. As young children growing up in Tanforan and Topaz Concentration Camp, my Grandma and Great-Aunt endured inhumane living conditions and the harsh conditions of the camps. My Great-Aunt May recalls the sunflowers as a powerful source of hope, beauty, comfort, and enchantment that brought beauty to the harsh concentration camp space of Topaz. This story reminds me that even in times that feel hopeless and in spaces of harm and oppression, we can plant seeds to create worlds of beauty, hope, and liberation.

Ellen Bepp shared her grandfather’s vintage Voigtlander Bessa folding camera: “The black camera is flat when closed but one little button releases the front section to reveal the intricate lens, viewfinder and leather accordioned section that pulls out. Before the war, he owned and operated a photography studio on Kearny Street, San Francisco, so photography was a major part of his life. Most of his work was in portraiture so he provided an important photo-documentation service in the lives of his clients in his close-knit Japanese community. I believe this camera symbolized his connection to his community even though they were torn apart by the war. Perhaps this was a grounding influence during such a traumatic period in camp.

“I chose this item to honor my grandfather Kiroku Bepp’s creative legacy, which I believe he passed along to me in various ways since I became an artist myself. One lesson he taught me was to always ‘see’ and not just ‘look’ to be aware and sensitive to what is beyond the surface.”

From Ross Harano: “My grandparents, Rihachi and Tsutayo Mayewaki, were incarcerated at Jerome and later at Gila River. This note holder was one of several household items that were made from scrap wood during the Mayewaki family’s internment. The calligraphy on the bottom translates to ‘Endurance,”’ and the three blue stars represent three Mayewaki sons who volunteered to serve in the US Army. One son was seriously wounded during the Anzio landing in Italy.

“The note holder reminds me of the sacrifices made by my Issei grandparents and by my Mayewaki uncles who served in the 442nd and the MIS: M/Sgt Ben Mayewaki, MISLS Section 7; T/Sgt Hachiro Mayewaki, MISLS Section B-8; Pfc Charles Mayewaki, 442, 2nd Battalion, Company G PH, CIB.”

Janet Kramer wrote, “My submission is a white cotton doily crocheted by my mother, Nobuko Enkoji Matsumoto. The diameter is about 16” and there is a windmill motif in the center of what could be the image of the sun or a flower.

“My mother entered Minidoka when she was 17, during her senior year in high school. When I was growing up, I noticed that she had several crocheted doilies, runners and tablecloths and I once asked her where she learned to do all this. She told me that she learned to crochet in camp. I chose this piece to submit because the windmill-like motif in the center reminds me of her stories about the constant wind in Minidoka and how their living quarters were always full of sand. But most of all, this little doily symbolizes my mother’s industriousness and her lifelong habit of continuously putting her hands to good use, whether it be cooking, cleaning, crocheting, knitting or sewing. Her hands are finally at rest.”

Kathy Takemoto shared this memory from her mother’s time in camp, represented in the image of a shamoji, or rice paddle:

“My mother, Kazuko Nakata, and her family were at Poston, Camp 1, Block 2, Apartment 9. As an 11 year old, she and other children would wait in the dining room until the rice was served and the pots were empty. Then, the cooks would scrape the bottom of the pots with a shamoji and distribute the burned/toasted ‘sheets’ of rice to the waiting children. For my mother and the children, these toasty bites of rice were a treat to look forward to and provided a moment of delicious happiness while interned.

“My mother felt the stress of camp was pronounced among the adults compared to the children. She was old enough to understand why the JA’s were interned, felt the injustice of it, but as a child, made new friends and found experiences which brought fleeting moments of happiness. Her mother, Sakashi Nakata, was employed in camp as a cook’s helper, receiving $16 per month salary.”

—

[Header: Some of the paper memory objects laid out on a table before being added to the net. Photo by Natasha Varner.]