May 19, 2020

On the afternoon of April 15th, detainees at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington filled the narrow triangle that serves as the facility’s recreation area. In a carefully choreographed movement, they marched into formation to the universal signal of distress. This act of creative resistance coincided with a hunger strike organized by detainees at the privately-run detention facility.

The protestors’ demands were simple. Given the current global health crisis and the inability of ICE to adequately protect detainees — not to mention guards and other staff — from the disease, the center must close, they said. “The SOS distress signal is our desperate call for help from every elected official to respond and do whatever they can do to get us out now. Our lives are in imminent danger and we do not want to die in detention,” the detainees wrote in their list of demands.

The hunger strike at NWDC was one of 16 similar protests held at immigration detention facilities across the U.S., according to Detention Watch Network. As those detained continue to fight for their lives, groups on the outside are rallying to support them. Among them, some Japanese Americans are making the case that their own history offers stark evidence about the perils of epidemics in concentration camps.

Managing Contagions in WWII Concentration Camps

Nobu Suzuki was a young mother in Seattle when she learned that she would be incarcerated along with all other West Coast Japanese Americans. Typhoid inoculations were recommended for all headed into the detention facilities, where sanitary conditions would likely be poor. Suzuki sought to help her community by securing some free shots from the city health department, but instead of helping, the head of the department yelled at her to “get out” and refused to provide the necessary inoculations because she was Japanese American.

“I was so disappointed, and at the point of crying, and left his office,” Suzuki said. She soon learned that her local Cannery Workers Union was willing to give her the needed inoculations if she could find someone to administer them. She set up a makeshift clinic with her husband, a doctor, and several nurses. “We gave the shots to whoever came,” she recalled.

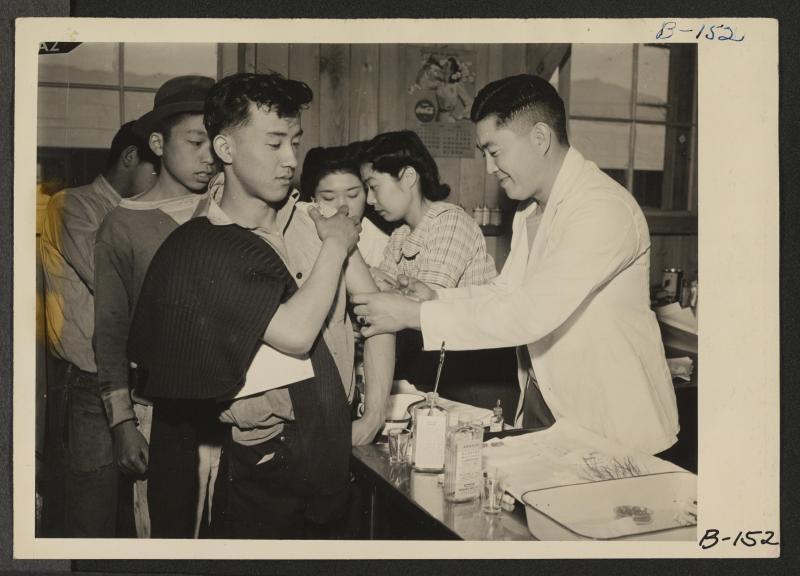

Despite the difficulty Suzuki faced in Seattle, typhoid shots were made readily available — and even mandatory — for most Japanese Americans. Before it had even officially opened as a WRA concentration camp, Manzanar had given some 14,000 inoculations to detainees between March and early May of 1942.

Administered in a series of three shots, the typhoid inoculation cycle often began during the removal and registration process, then completed at the temporary assembly centers. Detainees were required to carry “injection cards” with them in order to prove that they had completed the routine.

In the Salinas detention facility, “typhoid delinquents” were compelled to get the shots through threats of public shaming:

“Within a few days, names of typhoid delinquents will be posted on the bulletin boards. Please watch for it. Your full cooperation is requested, warned “Physician-in-Charge,” K.Iwasa, in the Salinas Village Crier.

While there were no major outbreaks of typhoid in the camps because of this widespread effort, other infectious diseases proved more challenging to keep at bay. In fact, the camps often served as a breeding ground for epidemics. The threat was greatly heightened as a result of shared dining, toilet, and bathing facilities, and the notoriously poor quality of the food and water. Inadequate medical staff and supplies exacerbated the problem. Further, psychological distress and exposure to the elements left many of the residents with weakened immune systems.

Smallpox and measles were among the chief concerns, and prompted many of the camps to open infectious disease wards. But illnesses like flu, dysentery, polio, valley fever, whooping cough, and malaria also threatened to spread rapidly through the tightly packed barracks.

In response to one polio outbreak in southern Colorado in the summer of 1943, all activities were banned at the Amache/Granada concentration camp. Detainees were ordered to stay inside and kill as many flies as possible, and to eliminate standing water in order to stop the spread of the insect-borne disease.

Unlike many camp administrators, E. Ray Jonson, Amache’s assistant project director, acknowledged that the conditions at the camp made detainees more vulnerable:

“Residents are exposed to polio, more than an outside community with buildings so close and with the serious problem of proper sanitation in mess halls, laundries, and latrines.”

Combatting the “White Plague”

Tuberculosis proved to be one of the most challenging diseases to manage in the camps. Although it was no longer the leading cause of death in the United States, tuberculosis was still a major health concern during WWII, with an effective antibiotic to treat the disease eluding researchers until the late 1940s.

Beginning in the late 1800s, doctors and climatologists started recommending that those suffering from the disease relocate to arid and dry climates above 2,000 feet, which they believed could provide untold health benefits. As Sara E. Grineski, Bob Bolin, and Victor Agadjanian have documented, these so-called “lungers” flocked to Arizona and other southwestern states and took up residence in fashionable health resorts for the wealthy, while the indigent were crowded into sprawling tent cities.

The conditions inside Japanese American concentration camps had the potential to accelerate the rate of infection. Containment was a challenge given that an ill person could be relatively asymptomatic and could spread the disease through something as simple as a shared plate of food or wash basin in the mess hall. In efforts to contain the epidemic, the WRA built a dedicated sanatorium in the ruins of an old post office at Gila River. Some Japanese Americans who contracted tuberculosis at the other camps were sent to Gila River in the hopes the high, dry desert air would help them to recuperate faster.

Kay Matsuoka’s husband was one of the first patients to be held in the Gila River sanatorium. She recalled the shame that came with the stigma of being married to a tubercular:

“It kinda hurt me, and it made me feel very sad, too, because when I lost all my friends that used to come and see me, nobody came. And then, especially when they, all the nurse’s aide would go to any other wards, but they wouldn’t come to the TB ward. And that’s what really, you know, ’cause we were all in together as a result of the war. All fellow members, and it, that kinda really hurt me.”

Broader narratives about tuberculosis placed blame on the individuals who got sick by suggesting that the disease was caused by their own poor hygiene or genetic disposition, rather than the contagion itself. In his field report from Gila River, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study researcher Charles Kikuchi reports that the stigma was so great among Japanese Americans that some families even disowned relatives who became infected.

At the same time, fears about the disease’s communicability resulted in a chronic problem of understaffing in Gila River’s TB ward. By October of 1944, there were 57 TB patients at Gila River and such difficulty recruiting staff to care for them that patients were often left to care for themselves. The situation became so desperate that camp administrators entertained the idea of making the family members of the afflicted take on shifts at the hospital.

Staffing was also an issue at Poston, Arizona’s other WWII concentration camp. There, a special tuberculosis ward was created in the hospital in order to treat the growing number of patients. However, hospital administrators had difficulty recruiting doctors and nurses to live in such a hot and desolate place.

The relationships between medical staff and their charges in the TB ward were acrimonious and filled with mistrust. Black nurses were subjected to harassment and taunts from a select group of TB patients. After one patient exposed himself to a female nurse and demanded sex, he was formally admonished by fellow detainees. No further incidents were reported.

Patients who were diagnosed with active cases of tuberculosis were confined to lengthy hospital stays. However, they found the white doctors diagnosing them to be so incompetent that many felt they were being held unfairly. In August 1943, a group of patients demanded outside experts be brought in to proffer a second opinion on their cases. Others simply insisted that they knew they were healed and were ready to return home. Records show that one patient demanded to be discharged, arguing “This is my body. I know about my own body more than anybody else. That includes the doctors.”

As tensions grew, several patients agitated and defied orders to stay in the hospital, returning early to their barracks, including one active, far advanced tuberculosis patient, Seizo Tsuji, who presented a forged discharge notice to his block manager.

Hospital staff lacked the authority to demand that patients remain confined against their wishes. Instead of handling this potential health crisis through appropriate measures to treat and isolate patients, camp administrators tasked block managers with the job of curbing any potential epidemic. Fierce debate broke out among the block managers about whether it was fair to create a policy that would impact the entire camp, or if policies should instead be determined on a block-by-block basis.

Howard Kakudo, a detainee who worked as an artist at Disney prior to his incarceration, gave “an impassioned speech, arguing that Japanese Americans were lucky to be alive at all and should do anything necessary to keep each other safe from communicable disease.”

By February 1943, there were over 130 cases of TB in Poston’s Unit 1 alone, but only 35 were confined to hospital care. Additionally, a number of children had also tested positive. Poston was on the edge of an epidemic. A Temporary Community Council was formed to address the impending crisis. In a memo Franklyn S. Sugiyama, Chairman of the emergency council, warned:

“Picture the danger: 95 people running loose in this community who have been proven to be infected by tests conducted by the local medical staff. If no steps are taken to correct these conditions it will only be a matter of time before the whole community is infected with tuberculosis.”

Sugiyama noted that the hospital lacked both beds and staff to deal with a major outbreak, and urged administrators to immediately isolate those who had tested positive to two vacant blocks of barracks in Unit 2. As the camp weighed its options, the patient who had sparked the controversy decided to voluntarily return to hospital quarantine.

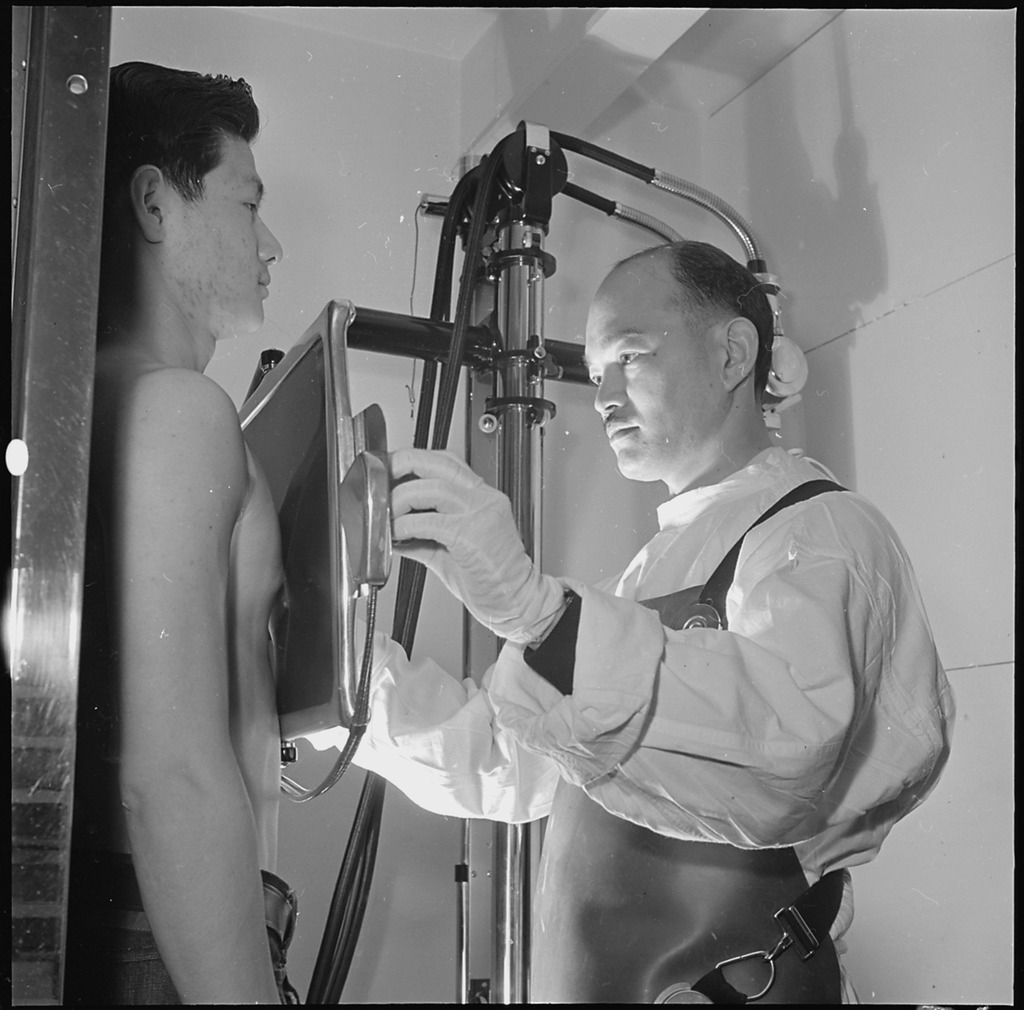

But the outbreak was still far from contained. In November of 1943, all residents of Block One were x-rayed to test for tuberculosis. Forty-seven new cases were discovered, but since there were not enough beds in the hospital to accommodate all, they were ordered to self-quarantine in their barracks and not share things like plates and utensils with anyone. However, there is no indication that separate bathroom or shower facilities were provided for the ill.

Barring an immediate solution for handling cases within the camp, administrators began transferring patients to the Phoenix Sanatorium for Indians, which had been established in response to the tragically high rate of infection at Native American boarding schools. A year later, in February 1944, Poston detainees organized a dance to benefit the Japanese Americans confined at the Sanatorium to make their stays “as pleasant as possible.”

In September 1944, the crisis had yet to be contained. The head of the Phoenix Sanatorium traveled to Poston to evaluate the tuberculosis patients, possibly indicating that patients continued to mistrust hospital staff. By June of 1945, the TB epidemic had yet to be fully contained and there was an uptick in cases among youth. Parents were urged to take proper measures to keep their children safe: “This insurance policy cannot be paid in money. Effort and constant watchfulness is what it costs.”

“Free Them All”

In the case of all camp epidemics and communicable disease outbreaks, the burden to remain healthy and disease free was placed on the detainees. It was framed as their duty to themselves and their community to inoculate when possible, to self-quarantine, to kill flies, to commit to extended hospital stays, and to report on fellow detainees.

But the true risk factor — the fact of their detention in crowded and unsanitary places — was never questioned by medical experts. Some Japanese Americans argue that the lesson we can take away from this history for the global pandemic we face today is this: rather than ask how best to protect incarcerated populations, we should be abolishing incarceration altogether.

Marge Taniwaki, who was quarantined with chicken pox as an infant at Manzanar concentration camp, did not mince words in demanding more humane treatment for detained immigrants today:

“Children of the WWII prison camps know the trauma of confinement. We demand the immediate release of all who are imprisoned in close quarters under unsanitary conditions, even as the coronavirus pandemic continues. The headstones in the cemetery at Manzanar are mute testimony to the deaths of inmates from inhumane conditions and lack of medical care. The US government must stop repeating history.”

Taniwaki shared her testimony as part of efforts to speak out against contemporary detention practices organized by Tsuru for Solidarity, a grassroots movement led by Japanese Americans, many of whom were themselves incarcerated as children during WWII, or have direct connections to that history

In the past year, Tsuru for Solidarity has staged protests at detention facilities around the country and is organizing a national pilgrimage to close the camps in Washington DC. Although the physical gathering has been postponed until next spring, the group has moved its organizing efforts online in an effort to use the moral authority of their own history to support undocumented immigrants in detention now. Their work has taken on a new urgency as the global pandemic unfolds.

Groups like Tsuru for Solidarity remind us that sites of incarceration present major threats to detained individuals, and these threats grow exponentially in the face of public health crises. Learning from history, in this case, isn’t a simple intellectual exercise. It’s potentially a matter of life or death.

—

By Natasha Varner, Densho Communications and Public Engagement Director.

This post was produced in partnership with The Abusable Past, a digital publication produced by the Radical History Review, and is cross-published on their website.

[Header photo: Survivors and descendants of Japanese American incarceration visited the remains of the Poston concentration camp during an October 2019 pilgrimage. Photo by Natasha Varner.]