September 8, 2025

Jaci Jones (she/her) is a Professional Learning Specialist at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, PA. She holds a B.S. in Secondary Education (Social Studies) from Penn State University and an M.A. in Holocaust and Genocide Studies from Kean University. Before joining the NCC, Jaci spent a decade teaching high school history and government in New Jersey, then transitioned to professional learning with Learning for Justice, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. She is passionate about empowering educators with best practices to ensure all students receive an equitable and honest education.

In a conversation with Densho Education and Public Programs Manager Courtney Wai, Jones reflects on her path into civic education, how to approach teaching the Constitution with honesty and care, and what lessons it offers for understanding Japanese American incarceration and other moments when rights were denied.

Courtney Wai: To begin, can you tell us about your role at the National Constitution Center and what drew you to this work in civic education?

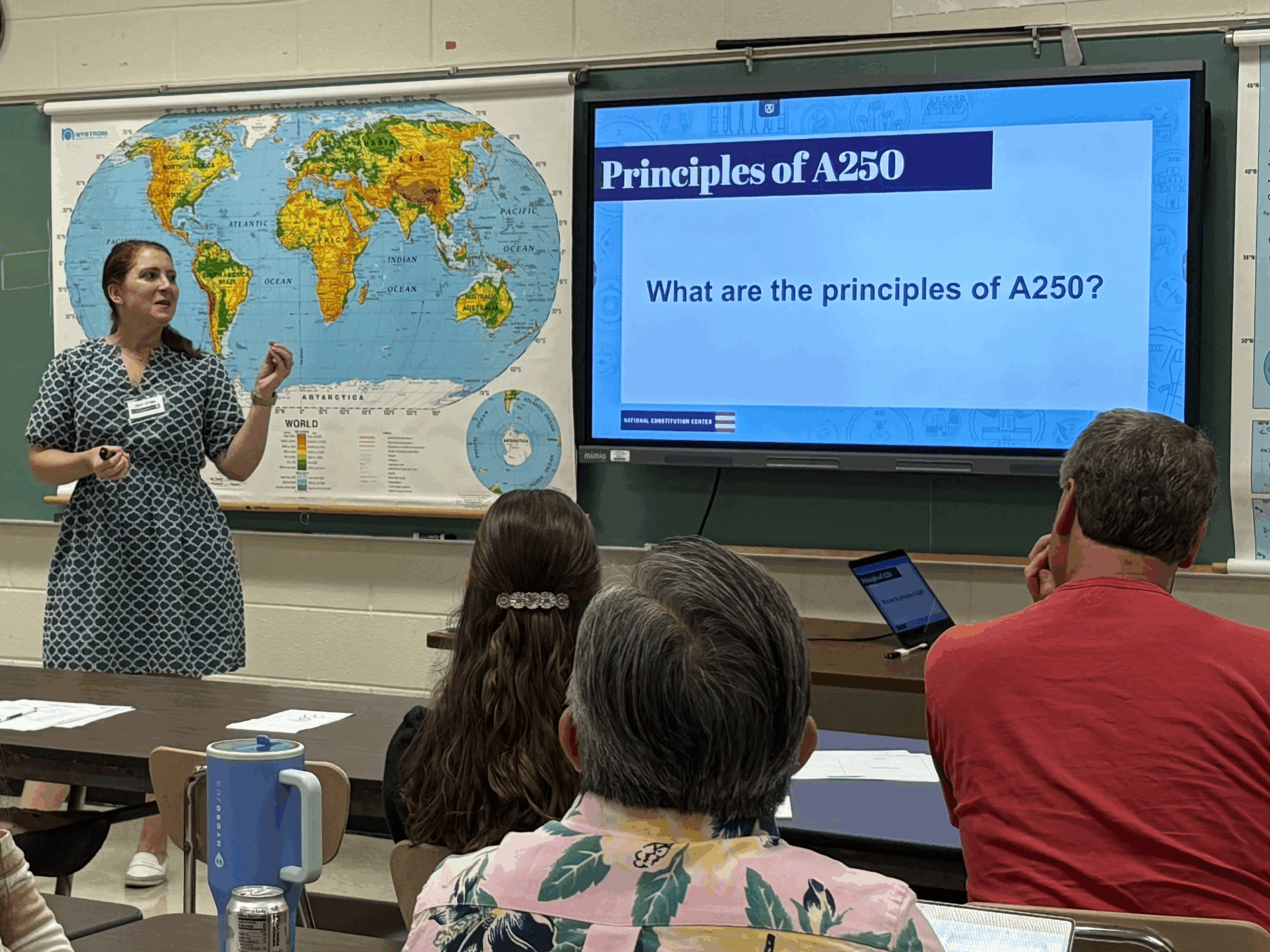

Jaci Jones: I’m a Professional Learning Specialist at the National Constitution Center. My main role here is to design and facilitate workshops for our K-12 educators nationwide on constitutional and historical content. We do this through our educational framework, empowering teachers not only to learn more about the Constitution and historical topics, but also to leave with practical strategies they can bring back to their classrooms to support student learning and civic understanding.

I think that’s what drew me to social studies education in the first place. I have always been really curious about human behavior, and I think at the heart of that concept is “We the People,” especially here in the United States. Who are we? What have our histories looked like, separately and together, and how does that impact the story of American history?

When I think about the role that people play, I think about the importance of being engaged and thoughtful citizens, and so when I was in the classroom, I lobbied for the AP Government and Politics course to be brought to our school, and was fortunate enough that our administration agreed it was a need across all three high schools in the district. I developed the curriculum, trained teachers, and helped bring the course to each school.

That’s why I’m really excited to bring it all full circle back to the National Constitution Center too, because I used a lot of their resources when I was teaching AP Government. As part of their Teacher Advisory Council, I was ground level when they started doing some of the student virtual programming that we do. Just knowing how impactful it was for me as a teacher and for my students, being able to now be on the other side and pay it forward for other educators is truly special.

CW: The Constitution is often taught as a fixed or neutral document, reflecting how many Americans see it. How can educators instead help students understand it as a living document, with historical relevance and contradictions that matter today?

JJ: One of our founding resources here at the NCC is our Interactive Constitution. While it means interactive in a way that you can navigate different assets that we’ve curated and explore it digitally, I also don’t think it’s by accident that we call it an Interactive Constitution, because the Constitution itself is meant to be interacted with and understood by citizens in the United States.

When I was teaching, I used to highlight that the text of the Constitution includes language about a “more perfect union” and an amendment process. The founding generation understood that America was going to evolve and change—maybe not to the extent that it has—but they knew that they wanted to make room for it to be adjusted and amended according to the will of the people, leaving the work of perfecting our union to future generations.

And so I think these are some of the big concepts that you would want students to understand when thinking about how history and historical events continually change the landscape of America. Understanding that our government—federal, state, and local—mostly has term limits, with the exception of the Supreme Court, and knowing there’s constant turnover in government, which brings change and an ebb and flow in policies and laws.

I think something else that’s important for students to understand is that Supreme Court cases really are an extension of the Constitution, because our Supreme Court justices are interpreting these laws to say whether they are constitutional or not, and that has a real impact on our everyday lives. Supreme Court decisions can be overturned or changed, reflecting our evolving understanding of the Constitution.

I think the more that we look to the past to understand what’s going on in the present, the more we can engage with our government in ways that will help impact the future.

CW: I really appreciate this idea that the Constitution is shaped by people, not just the other way around. That’s a perspective many don’t often consider. In today’s polarized climate, what guidance would you offer educators who want to teach constitutional history with honesty and care?

JJ: As a non-partisan non-profit institution, everything that we curate comes from bringing leading conservative and liberal thought leaders together with different interpretations of these bigger constitutional concepts and issues. With this foundation, the National Constitution Center serves as America’s leading platform on constitutional education.

When we put together our educational framework, we wanted to highlight this understanding of diverse perspectives and diversity of sources and texts to be able to engage in dialogue across differences, essentially allowing for multiple perspectives to be heard, and delivering the best educational programs and online resources that inspire citizens and engage all Americans in learning about the U.S. Constitution.

Our educational framework is a three-component pyramid:

- Historical foundations through storytelling: Whose stories are being told? Whose stories need to be uplifted? How do those stories weave together to build our understanding of the collective history of the United States? How do we as educators become really good storytellers so that our students are engaged in the content itself?

- Constitutional thinking skills: Once you know the stories and have the content, what specific primary sources or texts can help your students dig deeper, complicate that history, and illuminate it? These could be letters, Federalist Papers, videos, maps, or political cartoons. How can students pull textual evidence to defend their opinions and arguments as they engage in civil dialogue and reflection?

- Civil dialogue and reflection: Not debating, but engaging in honest discourse about the topic using evidence from the text. Reflection is also key—on both the content and on their participation in the dialogue itself. Did I allow my peers to share? Did we adhere to our classroom norms?

This complete understanding—stories, sources, dialogue—helps educators and students navigate polarization while engaging responsibly.

CW: I think it’s important to recognize that students can grapple with complicated stories and the nuances they carry. With the 250th anniversary coming up, how do the founding principles of the United States highlight the importance of not only remembering and honoring the legacy of Japanese American incarceration, but also reckoning with it?

JJ: Great question. The 250th Anniversary has been heavily on our minds here at the National Constitution Center. A lot of our professional learning, programming, and resources are framed through the lens of the principles of the anniversary.

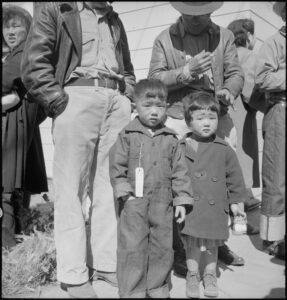

When we think about Japanese American incarceration and honoring and reckoning with that history, the principles that stand out are liberty, equality, federalism, and separation of powers.

A big question we ask is: Whose liberty? At the founding, oppression and enslavement of Native peoples and people of color were integral to the country. So when we say liberty, whose liberty was that? It’s important to ask these questions and use primary sources to illuminate the answers.

When we consider federalism and separation of powers, we see tension throughout history. In the foundational case Korematsu v. United States (1944), the argument was that President Roosevelt could incarcerate Japanese Americans in the name of national security—a tension between executive power and security that recurs throughout history. In 2018, this case was overturned—an example of the Constitution as a living document. While it took nearly 70 years, Japanese Americans received redress and reparations, unlike formerly enslaved persons and their families.

So, how can we use these stories of resistance and resilience through the Japanese American lens to foster hope and encouragement for other groups, and to continue questioning liberty, equality, and justice today?

CW: Thinking about the intersection of Densho’s work, which focuses on teaching Japanese American incarceration, how would you guide educators in approaching historical moments when constitutional rights were explicitly denied? And why is it so important for students to examine these moments?

JJ: Absolutely. This comes down to another essential component of our framework—emphasizing the difference between political questions and constitutional questions. It’s not just about “What should the government do?” but “What may the government constitutionally do?”

For example, in Korematsu v. United States (1944), the majority upheld incarceration. But dissenting justices wrote powerful opinions acknowledging constitutional rights were being violated. Justice Owen Roberts wrote:

“It is the case of convicting a citizen as a punishment for not submitting to imprisonment in a concentration camp based on his ancestry, and solely because of his ancestry, without evidence or inquiry concerning his loyalty… If this be a correct statement of the facts… I need hardly labor the conclusion that constitutional rights have been violated.”

Presenting both majority and dissenting opinions helps students see tensions in constitutional interpretation. It shows that even at the time, there were voices recognizing injustice. This can fuel students’ understanding of complexity and inspire them to fight for equality and justice today.

CW: You’ve mentioned the NCC’s framework, but you also have many concrete resources. Could you share some related to Japanese American incarceration, and what key takeaways you hope educators and students gain from them?

JJ: I’ll highlight a few:

- Supreme Court Cases Library: This includes landmark cases curated with scholars from diverse perspectives. For Japanese American incarceration, Korematsu v. U.S. is central. Pairing it with U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), a landmark birthright citizenship case, helps students understand different constitutional outcomes under the 14th Amendment.

- Interactive Constitution: Scholars from across the political spectrum interpret and debate clauses, including the 14th Amendment. Students see both shared interpretations and differences.

- Constitution in the Headlines: This includes recent resources, like spring 2025 materials on birthright citizenship cases—connecting history (1898, 1944) to today.

- Founders’ Library: These are primary texts spanning American history: philosophical works, speeches, essays, statutes, and personal accounts. For example, we have a 1943 statement from a Japanese American man at Manzanar, plus sources like the Chinese Exclusion-era debates, the Espionage Act (1917), and the Sedition Act (1918). These contextualize incarceration in broader struggles over liberty, equality, and security.

The takeaway is that looking at diverse stories through the lens of the 14th Amendment and connecting them across time helps students understand inequities and resilience. It underscores the Constitution as living and our role in shaping it.

CW: How can educators help students connect the history of Japanese American incarceration to constitutional issues that still matter today, in ways that also inspire hope?

JJ: One of the reasons I became a history teacher is because I understand that how humans interact is based on historical context. There are also ongoing questions of executive power, police powers, and legislative powers. Understanding separation of powers and the Constitution’s “elastic clause” helps students see how branches can counterbalance each other.

Studying Japanese American incarceration in an honest way can help build an understanding of these parts of the Constitution that will support student learning. Specifically, it can help them assess the role of government, the division of power, and the protections of civil liberties that foster a better awareness of how our collective past directly impacts our communities today. History can be cyclical, so knowing more—through primary sources and court cases—deepens understanding of liberty and equality across history, and equips us to shape a better future.