October 28, 2025

Christian-Joseph Macahilig is an Outreach Coordinator with the UCLA Asian American Studies Center’s Foundations and Futures AAPI digital textbook project. He holds a B.A. in History and Adolescent Education Certification from The College of Mount Saint Vincent and an M.A. in American Studies with a concentration in Ethnic Studies from Columbia University. Before joining UCLA, Christian was a middle school Social Studies teacher between 2017-2023 in New York City. He is driven to elevate the voices of AAPI communities while ensuring that their stories and histories are taught with fidelity.

In an exchange with Densho Education and Public Programs Manager Courtney Wai, Christian shares how his journey from the classroom to community outreach continues to shape his commitment to advancing Asian American and Pacific Islander representation in education and creating spaces where those histories can be seen, heard, and taught with care.

Courtney Wai: Tell me about yourself. What path led you to your current role with the Foundations and Futures textbook?

Christian-Joseph Macahilig: I would describe myself as the loud artistic educator, but my journey in education and the Foundations and Futures project began much differently. My original career path was Nursing, but by the middle of sophomore year of undergrad, I realized that Nursing was not a program I was passionate about; it was actually history. Social Studies was my favorite subject and growing up a theater kid, performing or presenting in front of groups came naturally to me. I knew that I could find myself thriving in education. I graduated in 2017 with a degree in History and certification to teach Adolescent Social Studies for grades 7-12. From 2017-2023, I mainly taught middle school Social Studies classes—a challenging but fun group to work with.

Looking back, I would say my shift to outreach came from my time in the classroom. By the start of the 2022-2023 academic year, I had begun to question my place in education due to a lack of guidance from leadership. Additionally, there was a moment I recall back in February 2022. My school asked the teachers to spend a day focusing on Lunar New Year lessons and activities. As the only Asian teacher in our staff, I used my Public Speaking and Debate elective that I was teaching to educate students about the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) hate attacks that were ongoing. I clearly remember a student telling me in front of his class that “Asians deserved what they got during COVID.” I was stunned and rather than let my anger take over me, I asked the student why they thought that. The reason was interesting—from hearsay stories or misinformation from social media.

By that point in my teaching journey, I was already in the mindset of thinking about whose voices are missing in the historical narratives I taught, and this moment reinforced to me that something needed to be done about advancing AAPI Studies in the classroom—a curriculum that many of the schools I taught at lacked. I left education by the end of the 2022-2023 academic year, but there was a part of me that still wanted to be involved in education in some way. A colleague I met through the UC Davis Bulosan Center for Filipino Studies posted about the Outreach Coordinator with the UCLA Asian American Studies Center’s Foundations and Futures digital textbook project. I felt inclined to apply given my background in education and experience working with Filipinx nonprofit organizations, and I’ve been glad to be part of this work for the past two years.

CW: This textbook project sounds like such a timely resource for educators. Can you give us an overview of the project and how it came together?

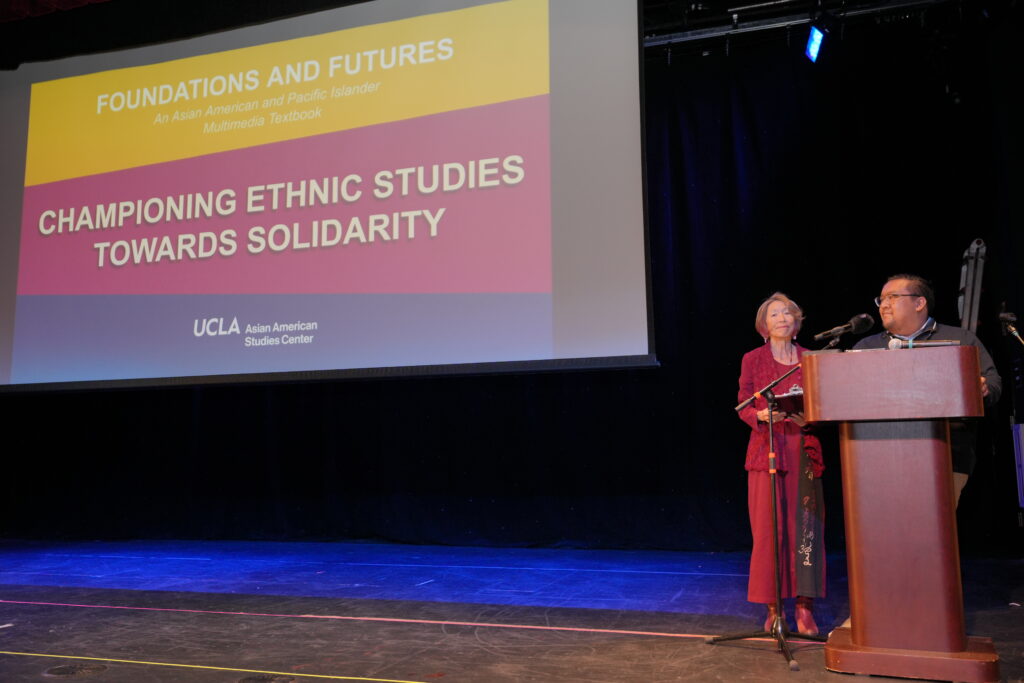

CM: The groundwork for Foundations and Futures began in 2020 through our co-directors, Drs. Karen Umemoto and Kelly Fong, who sought to address two urgent needs: the rise in anti-Asian violence during the pandemic and the absence of Asian American and Pacific Islander curriculum in our schools. There was also challenge and opportunity as California passed legislation that would establish an Ethnic Studies requirement for all secondary and higher education institutions—following the lead of Illinois with the TEAACH Act, which mandated the teaching of AAPI histories and cultures in public schools. Given that there was relatively little material on AAPI histories and perspectives, the Center and many other organizations asked the same questions: Who will teach our stories? Where can we find the curriculum that we can use in our schools? How do we train educators in Ethnic Studies to address the shortage of teachers who are qualified to teach about our communities with fidelity?

Through the support of the California AAPI Legislative Caucus, our Center received a $10 million allocation to develop a multimedia textbook. We commissioned a free 50-chapter digital textbook written by over 103 scholars in Ethnic Studies and AAPI Studies. Through additional partnerships and support from organizations like the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), National Education Association (NEA), and The Asian American Foundation (TAAF), a small team of three people grew to a staff of over twenty. By the time of our upcoming launch in early 2026, Foundations and Futures will be the most comprehensive curriculum on AAPIs available for everyone.

CW: Both the Foundations and Futures textbook and Densho center community voices and community scholarship. How can this approach change the way Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) history is typically taught or understood in classrooms?

CM: Centering community voices and scholarship challenges the idea that AAPI history is a separate or supplemental history, showing that our stories are deeply woven into the everyday fabric of U.S. history, from labor movements to arts and culture, from immigration to civil rights. We’re helping educators and students understand that our histories are part of the greater American experience.

I would say that both of our approaches give the art of storytelling back to the communities themselves. By blending scholarship, personal narratives, and multimedia storytelling, history becomes more alive. We are connecting research to real life—showing reflections of the world we live in now. Instead of having AAPI history being an occasional topic in a lesson, Foundations and Futures aims to help educators naturally integrate these stories into existing curricula.

Ultimately, centering community voices normalizes AAPI histories as part of our everyday histories. The classroom is more inclusive, the curriculum is more complete, and the lessons are more humanized.

CW: The Densho Digital Repository preserves personal stories through oral histories, photographs, and family documents—acts of memory that resist erasure. How does the Foundations and Futures textbook reflect this same idea of “memory as resistance”?

CM: I like this idea of “memory as resistance.” I would say that “memory as resistance” is definitely at the heart of the work that we’re doing respectively and collectively. Each chapter that we have commissioned—in addition to future ones we hope to add—is a collective act of memory. Our authors and contributors have created an anthology-style textbook that represents, honors, and preserves the histories of more than 20 AAPI communities from Native Hawaiian to South Asian to Pacific Islander experiences.

By presenting these histories digitally instead of a traditional print textbook, we are creating a living archive of rich resources that we cannot erase—a resource that grows and evolves as new stories, media, and perspectives are added. Each video, audio clip, map, photo, etc., helps preserve the voices and experiences that have shaped our country but too often go untold or omitted.

To me, that’s what makes Foundations and Futures so powerful; it’s an ongoing conversation with the present rather than just a record of the past. When students hear these stories more regularly, they begin to recognize how deeply connected our histories are. Memory becomes more than an act of “resistance”—it becomes an act of belonging.

CW: One of Densho’s values is community stewardship—ensuring that stories remain accessible and accurate, but always rooted in those who lived them. How do you see Foundations and Futures contribute to this shared goal of democratizing and humanizing history?

CM: Foundations and Futures contributes to this shared goal by centering community stewardship in everything we do. Our project was built as a multi-leveled collaboration, connecting universities, educators, students, and community members in a shared effort to make AAPI histories accessible to all.

Our collaborations and partnerships with organizations such as Densho, the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (APAC), and the National Educational Association (NEA) reflect the same belief: that history belongs to the people who lived it and to those who continue to learn from it. By keeping our textbook free and open-access, we remove traditional barriers to knowledge and make sure educators and students everywhere can engage with these stories.

In doing so, we’re not only preserving history—we’re creating spaces where communities can see themselves reflected in the broader American story. That’s how we democratize and humanize history: by ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to see their story as part of the collective “we.”

CW: As you look ahead to the launch, what do you hope educators and students will take away from Foundations and Futures? How do you imagine it shaping future classrooms?

CM: When I think about the launch—which I still can’t believe is just months away—I cannot help but reflect back on my time in the classroom. It was sadly evident how AAPI histories were largely absent in the curriculum or mainly focused on the “sadder” topics, including the building of Transcontinental Railroad, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and Japanese American incarceration. I wondered how history could look and feel different if every student saw themselves reflected in the curriculum.

That’s how I hope Foundations and Futures will transform classrooms: by building belonging and connection. For my fellow educators, I want them to feel equipped and inspired to teach AAPI histories as part of our shared history, not as just electives or supplemental lessons. When educators have access to stories that are rich, diverse, and grounded in community voices, they can help students see how intertwined our histories really are. For students, my hope is that they recognize themselves or someone they know in the stories they learn. Even for those who do not see themselves in those lived experiences, I hope that they build empathy and understanding.

If Foundations and Futures can help bridge those connections, then I think we’re doing the heart of our collective work: normalizing AAPI histories as part of everyday learning so that every student feels their story is part of the American story.

—

Foundations and Futures will launch in early 2026. In the meantime, sign up for Densho’s education newsletter to participate in virtual and in-person workshops exploring the Foundations and Futures textbook chapter on Japanese American wartime incarceration.