June 30, 2016

Japanese Americans celebrating the Fourth of July inside World War II concentration camps were especially familiar with this irony. A Manzanar Free Press editorial marking Independence Day 1942 sums up how many inmates felt about the festivities behind barbed wire: “For American citizens of Japanese ancestry herded into camps and guarded by the bayoneted sentries of their own country, it will be a doubly strange and bewildering day.”

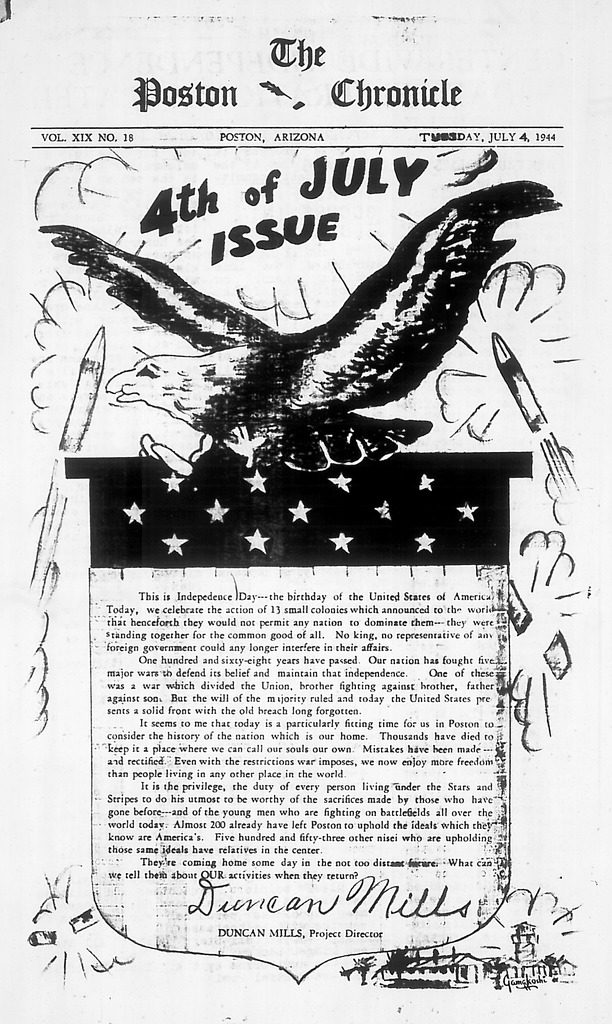

Accounts from the inmate-staffed but largely government-controlled camp newspapers are positive in their recognition of the holiday, featuring quotes from the Declaration of Independence, or praising Nisei soldiers fighting for democracy and love of country. Acknowledgements of injustice are weighted against hope for the future, anger tempered with a renewed appreciation for “liberty denied:“

Accounts from the inmate-staffed but largely government-controlled camp newspapers are positive in their recognition of the holiday, featuring quotes from the Declaration of Independence, or praising Nisei soldiers fighting for democracy and love of country. Acknowledgements of injustice are weighted against hope for the future, anger tempered with a renewed appreciation for “liberty denied:“

“Yes, cuss it out; say it’s a hell of a country. But only a democracy can correct its own mistakes. They’re not being righted as rapidly as we would like to have it, but the machine is pointed in the right direction despite the jolt received when the West Coast curfew and the exodus were ruled constitutional.

…We remember some of the carefree, joyous Fourths of our childhood and feel sorry for these evacuee tots. We hope July 4, 1944-5-6 and others to follow will not find them in the same plight.”

—Richard Itanaga, Denson Tribune, July 2, 1943

“Independence and freedom mean more to us now than it ever did before. Having been confined for three years, having been deprived of many of the privileges which we thought were ours by right, we now know that our lot is going to be an uphill fight that will continue long after the nation’s present struggle is over.”

—Gila News-Courier, July 4, 1945

Others make subversive digs at camp life. Yuk Kimura, writing for the Santa Anita Pacemaker, describes the building costs of the former race track and concludes, “So we are living in a $2,000,000 home. Boy, what class!” Ruth Ishimine, reminiscing in the Turlock TAC over “weenie bakes on the beach” and “colorful displays of fireworks as used to be on the Fourth,” jokes that there is “one consolation” to the subdued celebrations: “it’s hot ‘enuff.” And the Manzanar Free Press staff, winking at the underwhelming holiday menu, writes, “By next week we doubt whether there will be an able-bodied man left in Manzanar who can look a hot dog in the eye without flinching.”

While the public dialogue in camp papers paints a mostly happy picture, the diaries and field notes of researchers for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (a massive—and controversial—academic study of the incarceration) offer a more candid perspective.

“I get so tired of the flag waving. This war must mean more than that. It is supposed to represent a way of life to us.

…It is difficult to reconcile some things that have happened with true Democracy. Negroes are sent out to Australia to fight for Democracy; at home they don’t get a full share of it. Nisei boys serve faithfully in the army; their parents are sent to Tanforan.”

“[Camp director Elmer] Shirrell read a prepared speech on Independence Day and Democracy, but it did not click with the audience at all. He might as well have been talking over the radio because he was not talking to the Japanese people here. He did not mention once the plight of the Japanese, and hence could not show any sympathy for them.”

My personal favorite comes from Togo Tanaka:

“An unscheduled dust storm forced cancellation of the Fourth of July picnic Saturday, driving nearly 7,000 would-be picnickers into the shelter of their barrack rooms for the afternoon… Residents retired that evening, anticipating a windless Sunday, when the remaining half of the July Fourth program was to be staged. However, meat used in the sandwiches from several kitchens, was reportedly spoiled by the heat. Over 200 cases of diarrhea were reported in one block alone.”

Independence Day is a time to celebrate the many freedoms we are fortunate to enjoy in this country. It is also a day when we remember the struggles of the people who came before us, who fought and bled and endured so that one day their children and grandchildren could have what they were denied. We celebrate camp survivors’ legacy of resilience and hope (and, of course, the subtle art of poking fun at wardens administrators). We celebrate their efforts to ensure the mistakes of WWII are not repeated.

On this Fourth of July—as Muslim, Arab and South Asian Americans are targeted for surveillance much like Issei community leaders in the 1930s, as rhetoric echoing war-era anti-Japanese crusaders is inciting an epidemic of xenophobic hate violence, as our president vows to expand the unlawful detention of immigrant families—let us also remember that the work’s not done until we all get free.

—

By Nina Wallace, Densho Communications Coordinator

Updated 7/3/2017

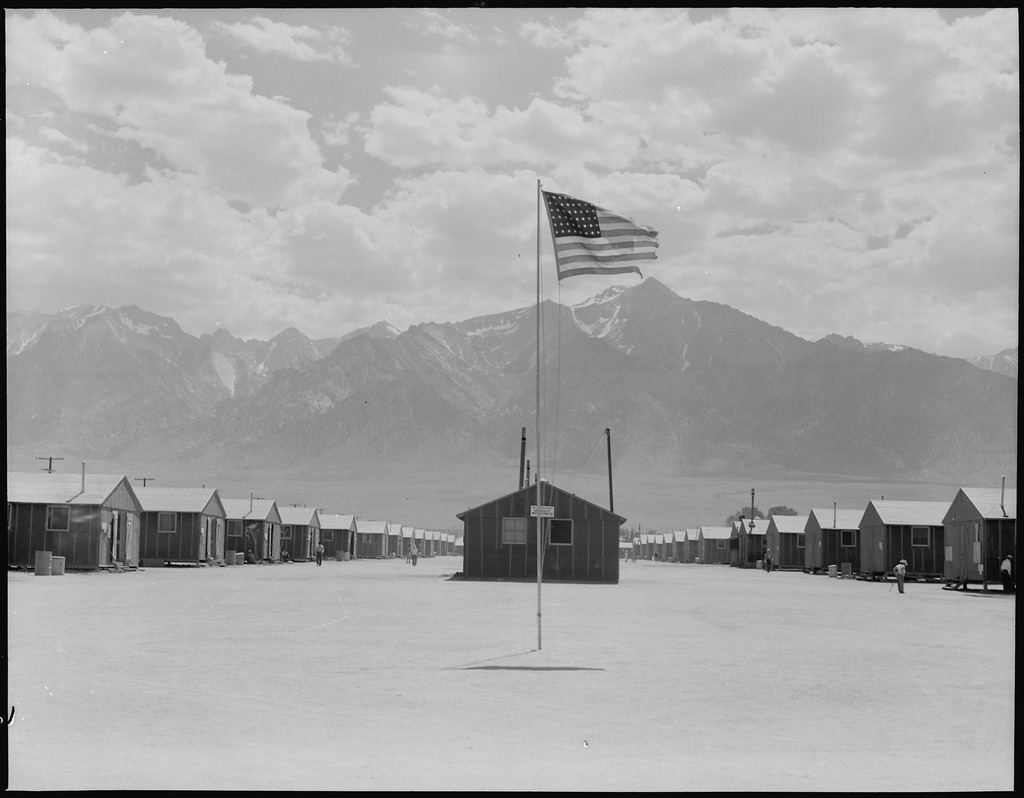

[Header photo: Original WRA caption: Manzanar Relocation center, Manzanar, California. Street scene of barrack homes at this War Relocation Authority Center. The windstorm has subsided and the dust has settled. July 3, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.]