October 5, 2015

The database makes it easier for both researchers and community members to learn about the 120,000 individuals who were incarcerated during WWII. It compiles information gathered from several sources, including census data taken at the beginning and end of the WWII incarceration period. Here, Kyle reflects on his experience at Densho, including an unexpected discovery about his own family’s history and gaining a stronger sense of the importance of preserving and understanding Japanese American history.

This last August I took a part-time summer internship at Densho where I worked mainly on cataloging items in the Akimoto Collection,* as well as looking into some ideas on how to improve the process of compiling a roster for all the Japanese interned in camps during World War II. I came into the internship with a fair bit of background knowledge on the WWII concentration camps that I learned in school and occasionally from things mentioned by a family member. However as a yonsei—a fourth generation Japanese American—I’ve always felt decidedly more American than Japanese and never really viewed the event with any sense of personal importance.

My first assignment was working on the Names Registry. I was asked to try to think of ways to streamline the arduous process of hand-transcribing microfilm rolls onto spreadsheets. The main problems were that this took a lot of time, required a large number of volunteers, and was prone to error in transcription. In looking for solutions, I focused on finding ways around these problems. One idea I came up with was a custom search algorithm that would let users search for terms with some given margin of spelling error. I thought this might help finding entries that had some sort of transcription error. After implementing the algorithm I began testing it by searching for various names in the rosters.

On a whim, I tried searching for my grandparents who I knew had been at the Minidoka and Manzanar camps. I found them, along with their family members, and was able to see the various pieces of information Densho had gathered about them. I have never asked my grandparents about their time in the camps, nor have they ever offered but I do know a lot about the lives they lived, and continue living, outside of that. That’s when Densho’s goal really struck me. The roster I was looking at wasn’t just a collection of names, birthdays, camp locations, etc. Instead, it was a list of 120,000 real people with real stories, both in the camps and outside of them, just like my grandparents. Densho was trying to collect as many of them as possible before they disappeared.

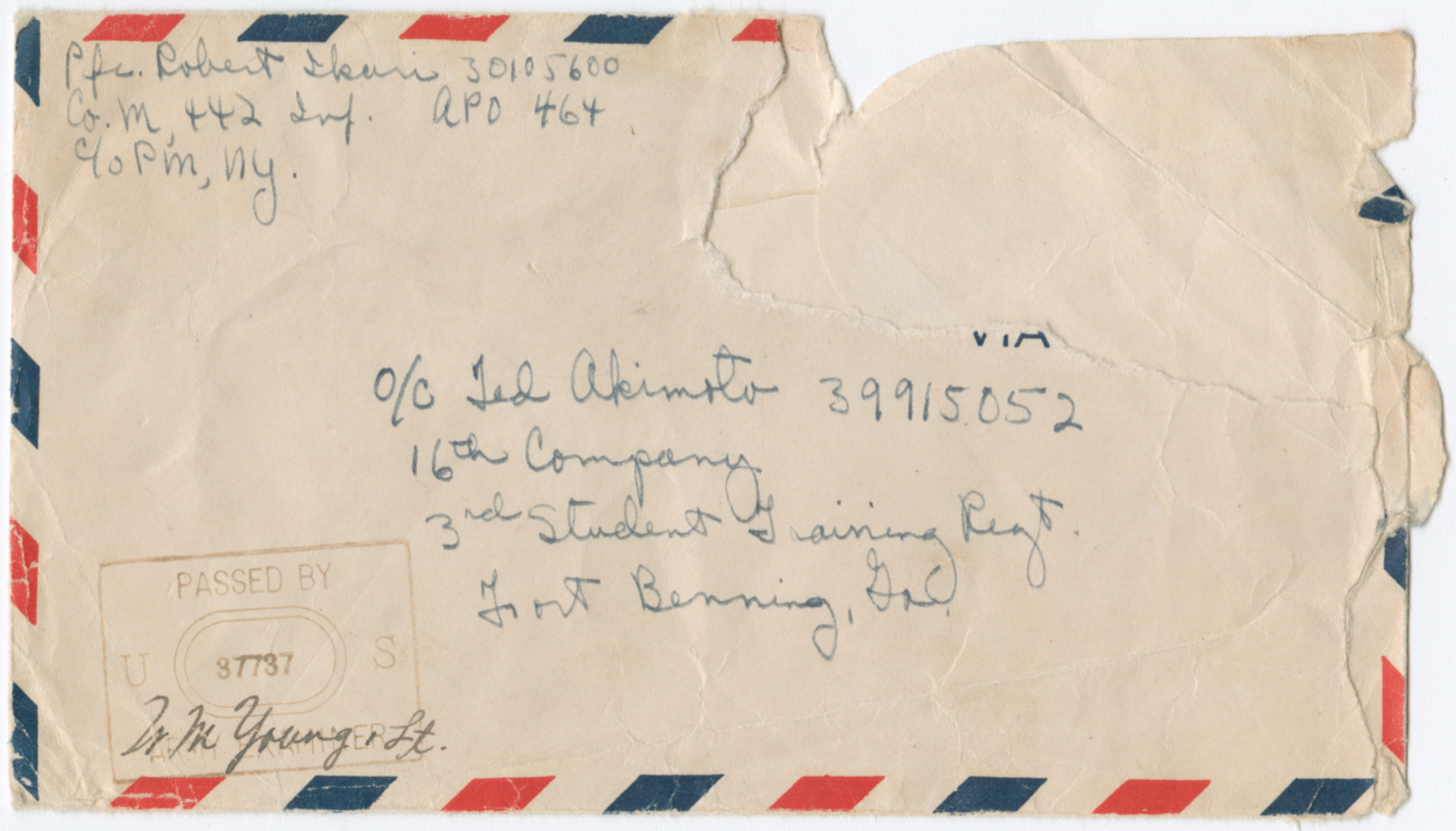

While I enjoyed working on the search algorithm for the roster, quite a bit of the work I did was cataloging the digital scans we had made of photographs and documents that individuals had lent to Densho. I cataloged 540 individual scans from items from the “Akimoto Collection,” which consisted mainly of photographs. The work was a little tedious at times, but it wasn’t without its own little surprises.

I looked up a lot of the more famous individuals and sites in the photos to more accurately catalog their data and, as a result, learned a lot of interesting details that I never learned in the classroom. These details included the fact that the infamous “Tokyo Rose,” the famous lady who voiced Japanese wartime propaganda, was actually an American; the crown prince of Japan had a Quaker tutor after the war ended; and that Prime Minister Hideki Tojo’s full acceptance of responsibility for the war during the Tokyo War Crime Trials was actually a good thing for the United States because they wanted to keep Emperor Hirohito from being implicated. Additionally, because almost all the photographs were from the American occupation of Japan following the war, they gave a face to the enemy the United States had spent so long fighting, something not always done.

Densho’s work as a cultural heritage organization is unique and cutting edge. I have seen firsthand that many other heritage groups want to adopt the Densho model of a digital repository to various degrees. Its effectiveness s unparalleled: not only educating people about the past, but also showing them that we are in danger of repeating these mistakes. I am extremely proud to have helped contribute in some way, even for a such a short amount of time.

*Densho received the materials in this collection from Summer Akimoto, the wife of Ted Akimoto. Ted Akimoto volunteered for the Army in 1943 and served in the 442nd, MIS, and the 71st Signal Service Battalion Photo Division. Visit Discover Nikkei to learn more about Akimoto’s service record. The photos that Kyle processed will be available in the online Akimoto Collection soon.