August 10, 2020

On this anniversary of the signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 we’re highlighting some recent additions to Densho’s archives that focus on the Redress Movement. Along with our existing digital content, these new collections together provide more information and context to the Japanese American communities’ decades-long struggle for redress. As we look to today’s growing conversations around reparations, we hope these stories can provide useful insight to how the Japanese American community fought for, and won, redress.

Frank Abe Collection

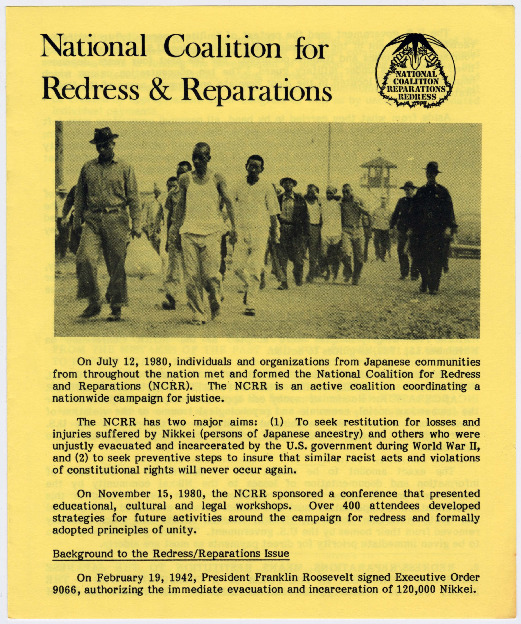

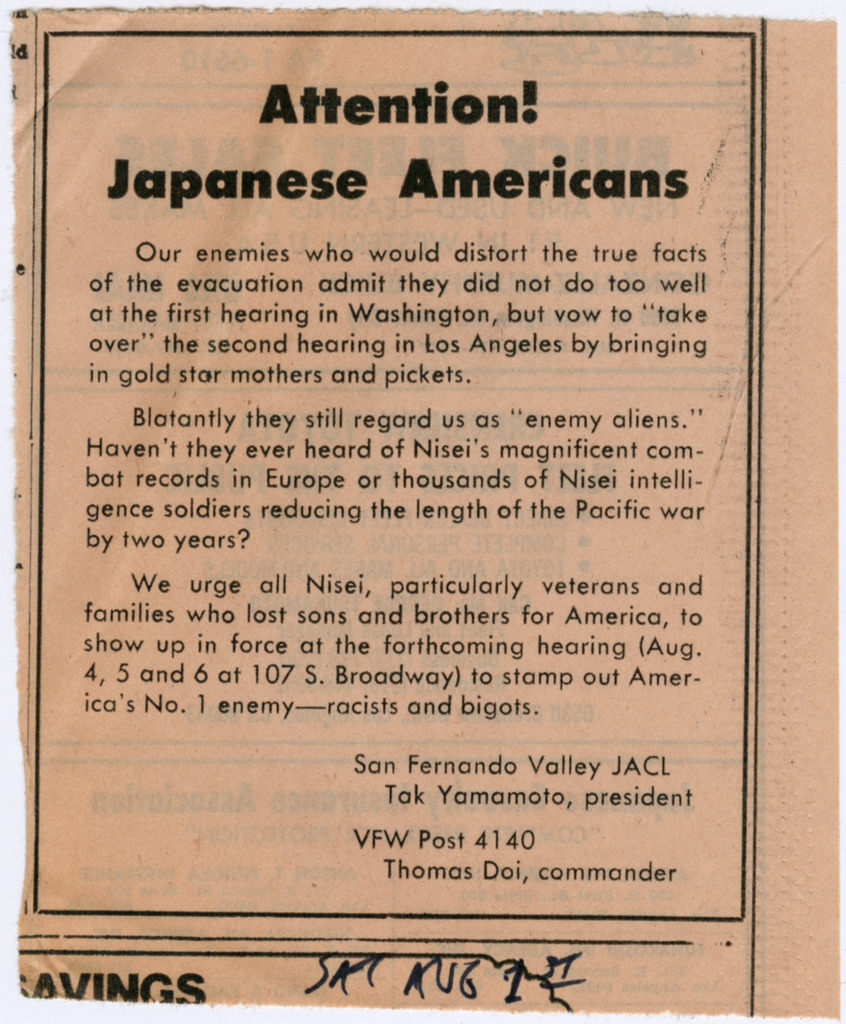

Activist, documentarian, and author Frank Abe’s collection—which he recently expanded—covers important milestones in the Japanese American campaign for redress and reparations, and the development of Days of Remembrance in Seattle and Portland. In developing his acclaimed documentary Conscience and the Constitution, Abe interviewed the original members of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee and other resistors. He was also part of the group that helped organize those first Days of Remembrance, and covered Gordon Hirabayashi’s appeal and the redress hearings in the 1980s as a journalist. The collection contains a wealth of oral history interviews, redress documents, Abe’s research materials, and much more.

Mizu Sugimura Collection

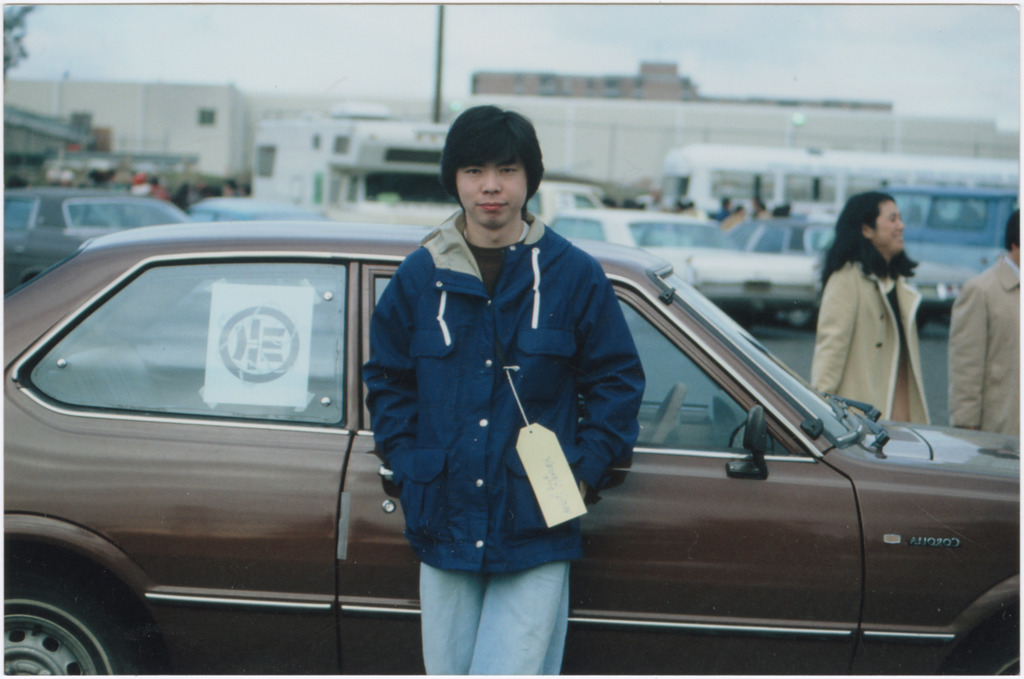

Mizu Sugimura and Yasushi Satomi were at that first Day of Remembrance, which Frank Abe helped organize. More than 2,200 people showed up at the old Seattle Pilots ballpark on the morning of November 28, 1978, and formed a four-mile-long caravan to drive down to the Puyallup fairgrounds, where Japanese Americans were detained in 1942. Sugimura and Satomi recorded their participation by taking photographs as people gathered at the beginning of the event.

Arthur Yakabi Collection

In 1980, after over a decade of grassroots organizing by Japanese American survivors of WWII incarceration and their descendants, Congress created a commission to review the facts around Executive Order 9066 and its aftermath. The following year, the Commission on the Wartime Relotion and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) held hearings on redress in ten cities. First hand accounts were the lifeblood of those hearings—and provided an outlet for survivors to break their silence and testify about their experiences. Arthur Yakabi, a Japanese Peruvian detained in the United States, was one of those who testified before the CWRIC. He was able to avoid deportation to Japan, thanks to the intervention of civil rights attorney Wayne Collins, but he soon learned that he and others forcibly brought to the U.S. had been labeled as illegal aliens:

My world fell apart! I was in jail and was to be shipped to wartime Japan. What was to become of me now? From my cell window I could see ships going in and out of the harbor. As each ship camp in I was sure it was the one that came to get me.

Then came Wayne Collins — to save me! I was so happy, I cried out in joy! I would soon be back in Peru with my family. Soon after that came news that Peru did not want us back, and more terrible news that the United States told me that since I did not have a passport, I was an illegal alien. All this time I was never accused of a crime, never had a trial. Now I was accused of entering the United States illegally. So here I was in jail with no papers and no country.

Yakabi’s heart wrenching story of being falsely imprisoned and shipped across the Americas is the focus of his collection and adds to our knowledge of the impacts of incarceration and redress for Japanese Latin Americans.

Kosai-Takemoto and Yoshioka Family Collections

Once redress was signed into law, the hard work of finding survivors and providing compensation came to the Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. The government began issuing redress checks of $20,000 to eligible survivors in order of age, beginning with a ceremony for the nine oldest survivors in October 1990. Copies of the letters individuals received as they navigated this process can be found in both the Kosai-Takemoto Family Collection and the Yoshioka Family Collection.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was the culmination of decades of work by hundreds of survivors and descendants of WWII incarceration. These materials are just a small sample of the many, many voices who were part of the Redress Movement—but they offer a fascinating, and often deeply personal, look at this larger history.

—

[Header photo: Women signing in at the first Day of Remembrance in Seattle, 1978. Courtesy of the Mizu Sugimura Collection.]