February 27, 2018

A year ago, from this podium, at the 75th remembrance of the removal of our people to inland concentration camps during WWII, we issued a call to action. Standing in solidarity with other targeted communities, we went into the streets and onto social media, we wrote letters to the editor, we joined protests, we gave educational talks, we made art, we made friends, and we formed alliances – all while using the moral authority of our community to say “Never Again”.

In the last year and a half, the New York Day of Remembrance committee has become active at a level not experienced since the days of the redress and reparations movement. The resurgence of white nationalists, with a sympathetic ear in the nations’ highest office, and the open, institutional and de facto racism of the right wing have made it imperative for us to speak out.

We have been working to promote the visibility of Japanese American voices of dissent in this period. We are working in union with community groups across the country to establish a unified movement of resistance to oppressive policies and of support to allied communities under attack.

We cannot stand by silently, knowing that 76 years ago our own community was being racially profiled, forced to register, and eventually incarcerated. We are called upon by our higher selves to stand in solidarity with those who are now being targeted and we are inspired by the powerful response of the Japanese American community nationwide and in particular of our own NY community.

****************

In the early 1920’s an undocumented Japanese immigrant teenager jumped his boat in Vancouver and crossed the border into Washington State. He was searching for a better life but he was alone. He was taken in by a Native woman from the Makah Tribe who helped him survive. He got a job working for a Scottish immigrant who was the lighthouse keeper in Neah Bay. He took a Scottish name, Robbie.

In Spokane, he found himself employed as a day laborer by an Irish immigrant couple, John and Addie Dunn. When offered his wages, he refused to leave. Crying, he told Addie he had nowhere to go. Addie, unsure of what to do, waited for her husband to come home from work. They then decided to offer this young teen a home, under one condition: that he would go to school and get an education. They raised him as their own son. His name was Gunzo and he was my paternal grandfather. The Dunns moved to Seattle and took over a seed and fertilizer store in the Pike Place Market where the first Starbucks is now situated. This Irish couple with their adopted Japanese son were unique. My grandfather helped run the store. The Dunns became known as the white merchants who would welcome the Japanese American and Italian American farmers nobody else would serve.

Gunzo married and fathered 7 children. His wife, Etsu, died in childbirth and my grandfather then married the store bookkeeper, Mary Doi, who I always knew as my grandmother. Shortly after, Gunzo died of cancer, leaving his new young, wife with 7 young step-children. The Dunns arranged for the Ishiis to live next door to them and co-raised all of the children with my grandmother. My father lived with the Dunns and considered them both his grandparents and his parents.

When the community was forcibly removed to concentration camps, the Dunns looked after Japanese American farms. They paid mortgages and bills, offered loans (that they never collected), and thereby assured for many that their farms would be waiting when they returned to Seattle after the war.

This story has always guided me. It highlights a theme that the NY DOR has been working to promote and practice in this last year: the meaning and strength of being an ally.

For the Dunns, there was no obvious personal gain in embracing my family. In fact, by societal standards they had much to lose, and I assume they got backlash for their loyalty and friendship. They tied their fates to ours. But they benefited greatly and they were the first to recognize the richness of their life.

As a child, I believed that the Ishiis were the lucky ones, befriended and assisted in time of a great need. But I now understand this more broadly.

When we choose to take a principled position and refuse to abandon our connections to other human beings, even if at great cost, we affirm the power of our essential humanity. The human spirit endows us with faith against despair, and in embracing our essential humanity new opportunities are created. We are all connected: the native woman who helped my grandfather visited him for years in Seattle, the lighthouse keeper who gave him a job is remembered because my oldest brother bears his name, and the Dunns, a childless couple, inherited the richness of a large and loving family. These relationships remind us of the complex inter-weavings of human existence.

In this time when division seems to rule the discourse, events like today’s Day of Remembrance remind us that our human interests are mutual. Relationships are the basis of enacting change.

This past year, NY DOR and other Japanese American organizations across the country mobilized. In doing so, we found solidarity with many communities that we now consider allies and friends.

These communities welcome our support, but we note that this has been profoundly important for our own liberation and healing as well. We have found a resurgence of pride in our community. We have re-engaged our own voice, we have told hidden stories of incarceration more publicly and shed humiliation and shame in the process, we have honored and celebrated the strength of our elders and the survivors of the camp experience.

—

Adapted from a speech delivered by Michael Ishii on February 24, 2018 at an event hosted by the New York City Day of Remembrance committee. Ishii is a yonsei originally from Seatac, Washington. As a teenager Ishii interned with Cherry Kinoshita for the Washington Coalition for Redress and Reparations and has been involved with community organizing projects committed to healing the intergenerational effects of WWII incarceration all of his adult life. He is the Co-Chair of the New York Day of Remembrance Committee and a member of the Tule Lake Committee. He currently lives in Sunnyside, Queens, NY.

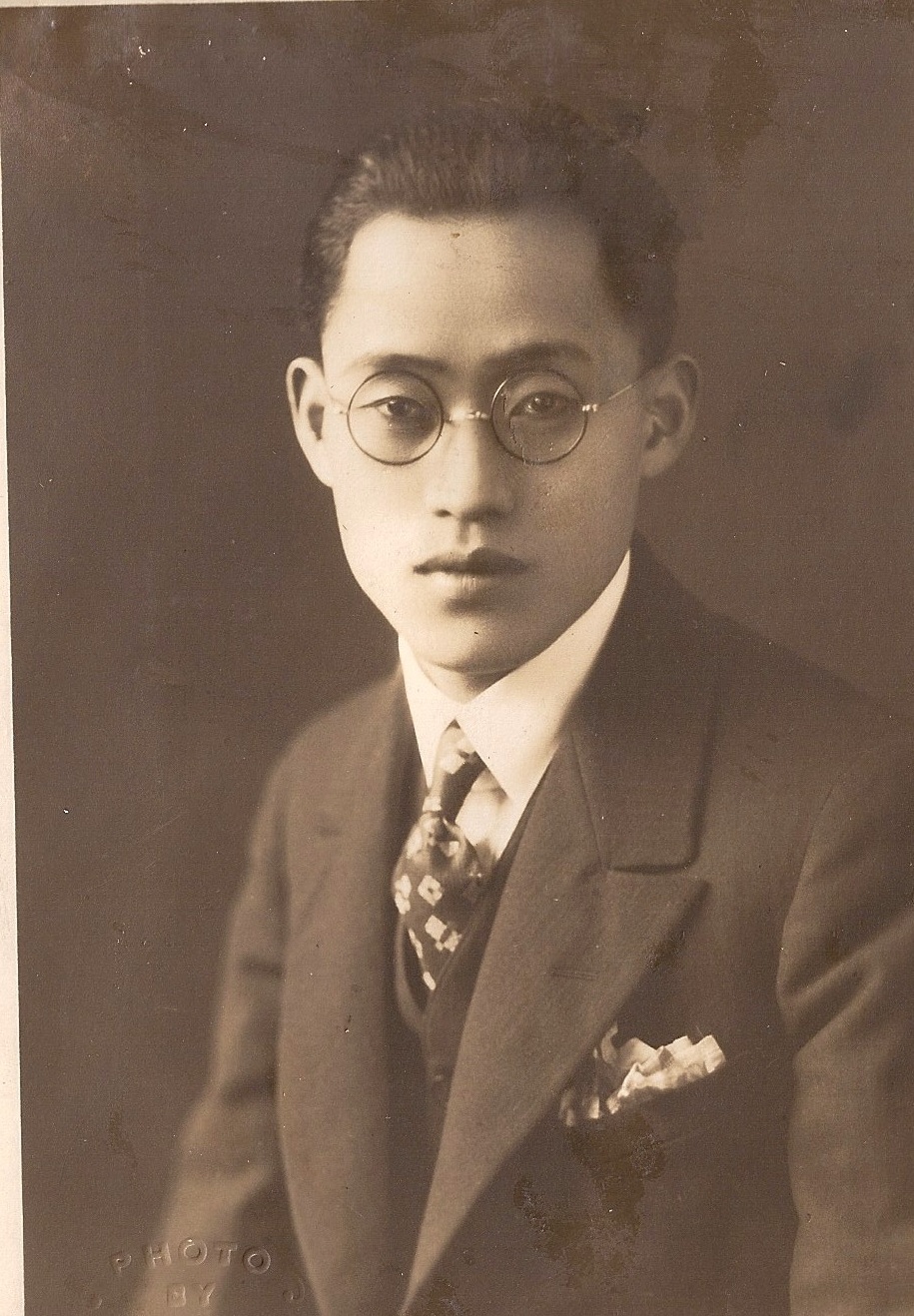

[Header photo: John and Addie Dunn of Dunn Seed and Fertilizer Store, Pike Place Market. Photo courtesy of Michael Ishii.]