June 6, 2017

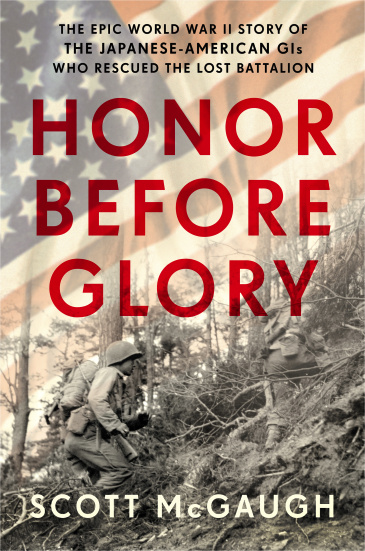

But as it turns out, Scott McGaugh’s Honor Before Glory: The Epic World War II Story of the Japanese American GIs Who Rescued the Lost Battalion, does add to the literature by telling a narrowly focused story on one episode: the legendary rescue of the “Lost Battalion” by the 442nd in the hills and forests of northeast France in late October 1944. While the general outline of this story is well known—that the 442nd “saved” a battalion of white soldiers who found themselves surrounded by the enemy, in the process losing many more men than they saved—McGaugh’s detailed account tells a much fuller story, not only of the rescuers but of the saved, of the enemy, and of other players who have mostly been left out of prior accounts. While Honor Before Glory doesn’t fundamentally change our understanding of this story, it certainly deepens it.

But as it turns out, Scott McGaugh’s Honor Before Glory: The Epic World War II Story of the Japanese American GIs Who Rescued the Lost Battalion, does add to the literature by telling a narrowly focused story on one episode: the legendary rescue of the “Lost Battalion” by the 442nd in the hills and forests of northeast France in late October 1944. While the general outline of this story is well known—that the 442nd “saved” a battalion of white soldiers who found themselves surrounded by the enemy, in the process losing many more men than they saved—McGaugh’s detailed account tells a much fuller story, not only of the rescuers but of the saved, of the enemy, and of other players who have mostly been left out of prior accounts. While Honor Before Glory doesn’t fundamentally change our understanding of this story, it certainly deepens it.

A prologue introduces us to several men of the 442nd and to the idea that the mission was at the same time both an extraordinary and costly achievement by the 442nd and of minimal strategic significance and questionable value from a broader perspective. The first two chapters set the stage. The 1st Battalion of the 141st Regiment, tasked with spearheading an advance into the Vosges Mountains advance easily, but are lured into a trap, finding themselves on a ridge surrounded by the enemy. McGaugh introduces us to the 442nd and its origins, emphasizing the Japanese American incarceration storyline and those that volunteered for the unit from concentration camps over the Hawai‘i element of the story. We also meet the man who is effectively the villain of the books, Major General John Dahlquist, who is portrayed as being both inexperienced as a battlefield commander, yet sure of himself, ambitious, ultra-aggressive, and a micromanager. As commanding officer of the 36th Division, he is in charge of both the 141st and the 442nd. We also meet the leaders of the 442nd and 141st as well as key German officers. Despite having just completed costly battles in liberating the towns of Bruyéres and Belmont and having been scheduled for a rest period, the second battalion of the 442nd is mobilized after less than a day to pursue the 1/141, with the 1st (the 100th Battalion) and 3rd put on notice.

The next five chapters take us day-by-day through the rescue, from October 26 to 30, introducing both familiar and unfamiliar elements to the story. We meet the leaders of the 1/141, who through no fault of their own, have been handed a dire situation. Lt. Martin Higgins, a New Jersey native of Irish descent, emerges as the leader of the trapped men and displays sound judgment in managing their scant resources and manpower. After losing a significant chunk of that manpower in an ill-advised patrol ordered by Dahlquist, Higgins manages to circumvent Dahlquist’s subsequent orders to attack. The German enemy is portrayed as having experienced and shrewd leaders but troops who are poorly trained, ill-equipped, and suffering from low morale. An interesting subplot centers on the heroic efforts by the 405th Fighter Squadron to drop supplies to the lost battalion. After several failed attempts, they finally are able to get supplies to the men on the afternoon of the 28th, restoring hope to them. Several more successful drops follow.

But the focus is on the 442nd. Their officers—commanding officers Charles Pence and, after he is wounded, Virgil Miller and battalion commanders Gordon Singles (100th), Janes Hanley (2nd), and Alfred Pursall (3rd)—are uniformly portrayed as brave and sincerely concerned with their men. Each also has run-ins with the seemingly omni-present Dahlquist. McGaugh also tells many stories of individual heroism and death, including those of Medal of Honor recipients Allan Ohata and Barney Hajiro. In addition to drawing on military sources and the many prior accounts, McGaugh also uses many oral histories from the collection of the Go For Broke National Education Center.

Two final chapters cover the 442nd through the remainder of the war and through the postwar years, focusing on the 2000 ceremony where twenty more Medals of Honor were awarded to the men of the 442nd after an army investigation concluded that racial discrimination had prevented more such awards at the time. McGaugh also fills in the postwar lives of the many key characters, recounting the story of how Singles rebuffed Dahlquist’s apparent attempt to make amends many years later.

Though McGaugh tells the complicated story clearly, the book suffers from a few flaws. Even with a helpful cast of characters at the beginning, there are simply too many characters, with many appearing for just a few pages, never to be heard from again. The book might have been improved with fewer key characters whom we get to know a little better. Though the history told is largely accurate, the author gets the date of the notorious Hood River incident wrong by a month (he says the Nisei names were taken off the memorial a few days before the rescue of the lost battalion, but this actually happened about a month later), misspells the name of Masayo Duus, author of one of the best prior accounts of the story, and uses “internment” to refer to the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans and “Hawaiians” to refer to Nisei from Hawai‘i. He also never really addresses the provocative issues raised in the prologue. While it is clear that Dahlquist treated the lives of the 442nd cavalierly, it is not clear that they were treated any worse than other units he commanded. But to what extent did the battle lack strategic significance? And was it really necessary at all? In the end, we don’t really know. Still, Honor Before Glory is a worthwhile and very human look at a story that many of us know both well and not so well at all.

—

By Densho Content Director Brian Niiya

[Header photo: Original caption: Co. E. of the 442nd Inf. Regt. comprising Japanese-American lads snapped in formation. Camp Shelby, Mississippi. 5/13/1943. Courtesy of the Seattle Nisei Veterans Committee and the U.S. Army.]